Australia is experiencing a record influx of international students that is causing immense pressure on Australia’s rental market and infrastructure and is helping to drive inflation higher.

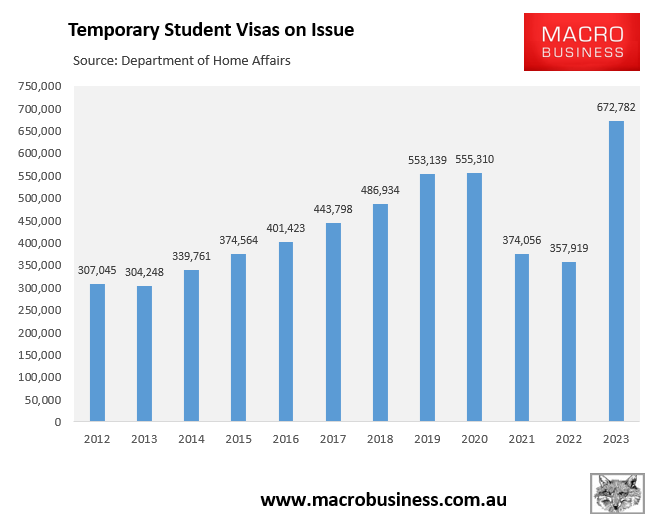

The latest temporary visa data from the Department of Home Affairs showed that there were a record 672,800 student visas on issue in October 2023, representing an annual increase of more than 300,000:

Student visa numbers in October were also around 120,000 larger than the pre-pandemic peak.

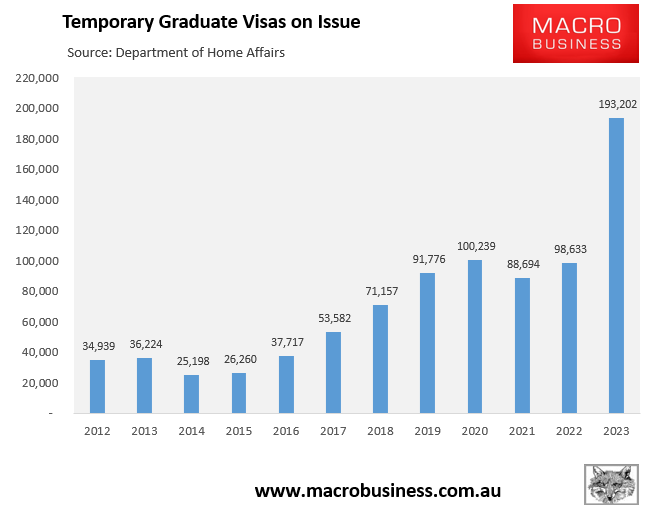

Graduate visas were also at a record high, with 193,200 on issue in October – an increase of around 90,000 on the pre-pandemic peak:

Combined, there were more than 860,000 student and graduate visas on issue in Australia in October, meaning that around one in 30 people in Australia were on either one of these visas: an extraordinary number.

To add further insult to injury, it looks like student visa numbers will continue to rise in the near term, with The AFR reporting on Friday that “universities are reporting historically high applications from international students to study in 2024”.

“Craig Mackey, director of corporate development at IDP Education, said the consultancy was tracking a 20% increase in foreign student enrolments in 2024, following a 77% rise last year”.

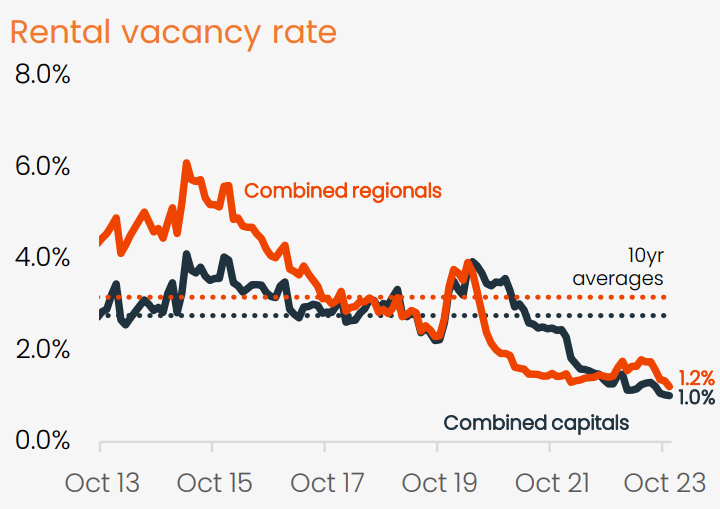

The massive increase in international students has been a major driver of the record tightening in the rental market, which has driven capital city rental vacancy rates to record lows and delivered strong rental inflation.

Source: CoreLogic

Given the unsustainable growth in student numbers, alongside the negative externalities caused (including driving-up rent inflation and interest rates), calls to both tax and cap international student numbers have grown louder.

As usual, vested interest from the higher education sector and immigration influencers are pushing back against policies that would cap student numbers or tax universities on their international enrolments.

Professor Merlin Crossley, deputy vice chancellor (academic quality) at the University of NSW, was the latest to lambast the idea of taxing international students, writing the following on Monday in The AFR:

“How can people be seriously proposing a levy that would drive universities to take more, more, and more international students – if they still come”.

“It is as if some people understand nothing about the higher education sector and research capability in Australia”.

“For those people here’s a lesson. In Australia, the full costs of research have never been covered by government research funding”.

“Where do these funds come from? International student fees. It’s a happy coincidence that those universities which most need research infrastructure are those most able to attract international students – so in a precarious way the system has worked”.

Professor Crossley fails to acknowledge that most of the research undertaken by universities is designed purely to propel them up the international rankings so they can attract more international students. It’s a complete and utter ponzi scheme.

How the international student ponzi scheme works:

In a nutshell, the federal government and Australian universities created a framework to encourage high numbers of full-fee paying international students via two channels.

First, the Australian government provides the world’s most generous student visa work rights and opportunities for permanent residency.

Second, Australian universities have lowered entry and teaching standards to allow greater numbers of students.

The cash bonanza generated by expanding international student numbers was subsequently channeled into research geared only at moving Australia’s universities up worldwide rankings, rather than areas that benefited Australians.

Because a higher worldwide ranking improves a university’s image and denotes excellence, universities used these rankings as a marketing tool to increase international student enrolment while justifying higher fees.

Meanwhile, actual classroom teaching quality has declined, with the student-to-academic staff ratio increasing significantly across Australia’s universities in tandem with the rapid increase in international student numbers:

International student cheating is pervasive, Chinese influence is rampant, and universities’ casualised staff are underpaid and pushed into passing low-performing foreign students.

Domestic students are also required to help non-English speaking students complete their courses through group assignments.

Local students are paired with international students, which frequently results in domestic students completing the majority of the work, thereby becoming unpaid tutors and cross-subsidising international students’ grades.

In essence, the education industry has devolved into an immigration racket, with institutions serving as migration agents rather than educators.

University vice-chancellors in Australia have been rewarded with million-dollar salaries for effectively transforming their universities into low-quality, high-volume migration agencies run for maximum throughput and profit.

What a marvelous ponzi scheme for Australian universities: 1) bring in plane loads of international students. 2) pump the fee revenue into research. 3) achieve a high ranking. 4) use it to market for more international students. 5) rinse and repeat.

Meanwhile, the actual experience of local students continued to degrade, as documented by The Australian in June:

Four of Australia’s large research universities are among the worst rated by undergraduate students for educational experience, with the universities of Sydney, Melbourne, NSW and Monash clustered near the bottom of the latest official survey”.

“The University of Sydney was given a positive rating by only 68.8% of its students in the federal government-backed survey, with the University of NSW only slightly better at 69.9%, the University of Melbourne at 71.8% and Monash University at 72.7%”.

These universities have among of the highest proportions of international students in the world, and the rankings rewards them accordingly.

It’s a great system, unless you are a local student. Or a tenant crush-loaded in Australia’s rental market.

Let’s be real. Running low-quality student visa mills for maximum throughput was never in the national interest.

Unfortunately, the Albanese Government has added to the farce by expanding post-study work opportunities and migration pathways, particularly for Indian students.

What about the proposed “tax” on international students?

Australian universities are non-profit organisations and currently do not pay tax (unlike other ‘export’ industries). This is despite universities acting like corporatised, profit-maximising businesses with senior leadership groups that get paid exorbitant salaries.

The universities, rather than taxpayers, are therefore ‘clipping the ticket’ and collecting the economic rents from Australia’s immigration system via student fees.

A levy on international students would ensure that Australians receive a financial cut from the trade, similar to how a sovereign wealth fund collects revenue from mineral exports.

A levy is also good economics because: 1) their demand is very inelastic, and will not change their numbers much, and 2) universities are making unearned rents due to location and prospects for immigration, not effort.

Other policies are also required:

Numbers could also be effectively ‘capped’ if the federal government required that universities provide on-campus accommodation for international students in proportion to the number of enrollments.

This would take direct pressure off the rental market and ensure that the costs and benefits to universities and Australians from the international student trade are more aligned.

Other ways to lower international student numbers could involve:

- Tightening entry requirements, including English-language proficiency and proof of finances.

- Tightening licensing and performance standards for private colleges.

- Penalising poorly performing institutions and closing down ‘ghost colleges’.

- Capping the amount of finder fees and kickbacks that can be paid by institution to education and migration agents.

- Reducing the generosity of work rights for international students and graduates.

Regardless, Australia must aim for a smaller number of higher-quality students.

Universities and private colleges must be stopped from privatising the gains from unprecedented volumes of international student enrollments while the costs are borne by Australians at large, particularly renters.

Sadly, I hold little hope of the federal government reducing student numbers to sensible and sustainable levels, given Labor recently signed two migration pacts with India with the explicit aim of boosting the number of Indians studying, living and working in Australia.