MB has long questioned the dubious relationship between our universities’ reliance on international student fees and university rankings, which we call a “ponzi scheme”.

In a nutshell, the federal government and Australian universities created a framework to encourage high numbers of full-fee paying international students via two channels.

First, the Australian government provides the world’s most generous student visa work rights and opportunities for permanent residency.

Second, Australian universities have lowered entry and teaching standards to allow greater numbers of students.

The cash bonanza generated by expanding international student numbers was subsequently channeled into research geared only at moving Australia’s universities up worldwide rankings, rather than areas that benefited Australians.

Because a higher worldwide ranking improves a university’s image and denotes excellence, universities used these rankings as a marketing tool to increase international student enrolment while justifying higher fees.

Meanwhile, actual classroom teaching quality has declined, with the student-to-academic staff ratio increasing significantly across Australia’s universities in tandem with the rapid increase in international student numbers:

International student cheating is pervasive, Chinese influence is rampant, and universities’ casualised staff are underpaid and pushed into passing low-performing foreign students.

Domestic students are also required to help non-English speaking students complete their courses through group assignments.

Local students are paired with international students, which frequently results in domestic students completing the majority of the work, thereby becoming unpaid tutors and cross-subsidising international students’ grades.

In essence, the education industry has devolved into an immigration racket, with institutions serving as migration agents rather than educators.

Meanwhile, university vice-chancellors in Australia have been rewarded with million-dollar salaries for effectively transforming their universities into low-quality, high-volume migration agencies run for maximum throughput and profit.

In June, we witnessed Australia’s universities storm up the QS 2024 World University Rankings because of a methodological change that reduced the importance of “the ratio of the number of academics to students”.

As explained by The Australian’s Tim Dodd:

“What a gift it was two weeks ago when, instead of universities having to go to the QS rankings, the QS rankings came to them. A major change in methodology led to most Australian universities rising, some dramatically so, and three universities – Melbourne, Sydney and UNSW – vaulting into the world’s top 20”.

“A key reason behind Australian universities’ rise in the QS rankings was the QS decision to reduce the weighting on faculty to student ratio from 20% to 10%. (Faculty is the US term for an academic member of staff.) This measure (intended as a proxy for quality of teaching) is one in which Australian universities perform badly because of their large class sizes”.

“Ironically, it’s the reduced weighting on a poor outcome which was a major factor in Australian universities’ ranking boost”.

As shown in the chart above, Australian institutions rank poorly on this measure, so its reduction in weighting from 20% to 10% was a huge benefit.

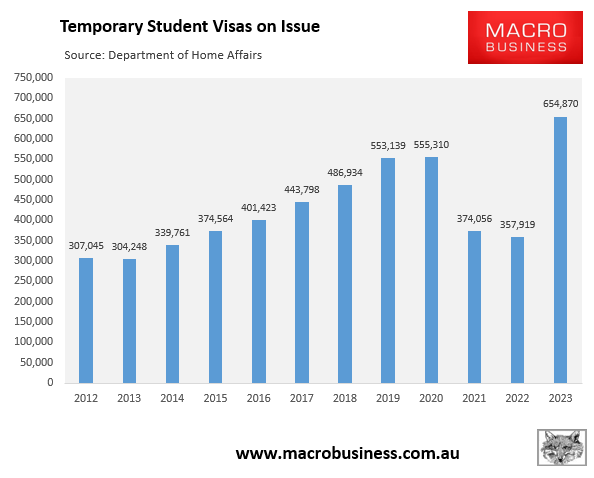

Hilariously, the Times Higher Education World University Rankings for 2024 have been released and shows Australian universities falling down the rankings due to a reduction in international student numbers over the pandemic.

The University of Melbourne is the only Australian higher education institution among the world’s top 50.

Melbourne University has fallen from 34th to 37 place in the latest annual rankings, while Monash University has fallen to 54th place. The University of Adelaide has fallen out of the top 100, having previously been ranked 88th.

Phil Baty from Times Higher Education says the latest data reflects Australia’s relative isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“First of all, while Australia is one of the world’s leading university sectors for attracting international talent and collaboration, the relative isolation of the country during the pandemic is showing up in the data, to detrimental effect on universities’ ranking positions”, Baty said.

“Real attention is needed to ensure Australia continues to be open to international talent, which includes the right policy incentives as competition for international talent heats up with possible shifts in the market”.

These rankings give extra points for the proportion of international students enrolled. Thus, having more international students equals a higher ranking (other things equal).

What a marvelous ponzi scheme for Australian universities: 1) bring in plane loads of international students. 2) pump the fee revenue into research. 3) achieve a high ranking. 4) use it to market for more international students. 5) rinse and repeat.

Meanwhile, the actual experience of local students continued to degrade, as documented by The Australian in June:

Four of Australia’s large research universities are among the worst rated by undergraduate students for educational experience, with the universities of Sydney, Melbourne, NSW and Monash clustered near the bottom of the latest official survey”.

“The University of Sydney was given a positive rating by only 68.8% of its students in the federal government-backed survey, with the University of NSW only slightly better at 69.9%, the University of Melbourne at 71.8% and Monash University at 72.7%”.

These universities have among of the highest proportions of international students in the world, and the rankings rewards them accordingly. What a farce.

Let’s be real. Running low-quality student visa mills for maximum throughput was never in the national interest.

Unfortunately, the Albanese Government has added to the farce by expanding post-study work opportunities and migration pathways, particularly for Indian students.

Student numbers have already rebounded to record highs, which will most likely be met with a march up the rankings next year as actual education quality collapses.