Dear God! Check this out from my old mate Guy Rundle today:

According to many — Greg Sheridan and Henry Ergas were the local representatives — China was a totalitarian state controlling every aspect of its citizens’ lives. But, they said, the rule of the Chinese Communist Party had nothing to do with the country’s galloping success over several decades, which was due either to the generic East Asian model, or just dumb luck.

It’s a pretty funny totalitarianism which has nothing to do with the economic life of its citizens. The conclusion is, of course, bunkum. Some on the naive right, the chino-pearls-Hayek-fanboy squad, are angered by the stubborn refusal of China to correspond to the idea that demands for political freedom shadow economic freedom. China has shown the opposite: give people a chance to improve their lives within a fairly stable framework, and such rewards will actively defer demands for political pluralism for decades upon decades.

For them, China essentially refutes a philosophy they have based their life on.

Rundle surely isn’t arguing that China’s economic rise was not driven by liberalisation? That’s just stupid. It even transpired at the political level for a while but, most importantly, it was the lifting of many previously banned economic freedoms under Deng and his successors that triggered the forty year growth spurt. That’s what capitalism with “Chinese characteristics” is.

More from the pulpit:

The importance of having a mixed economy, with 60% in state hands, was that funds could be steered towards infrastructure, and the country could bootstrap itself and build an urban working and middle class. Compare India, which has lurched from village socialism to neoliberalism, resulting in a “missing middle” between a rich elite, a residual working/rural poverty, and absolute poverty. Or compare Nigeria, which never managed to free itself from the capitalist world-system, with whole regions being as poor as they were at decolonisation. Or for that matter compare the Anglosphere West, which has talked its way into stagnation by allowing capital to starve demand by crushing wages and evading taxes.

For the Chinese, the goal of socialism remains. But it is not the slightly hippy, weave in the morning, seminars in the afternoon type thing of the 19th century. The CCP is clearly preparing for an era of nationalist post-capitalism, one in which automation and cybernation reduce capitalist accumulation in key sectors to a level that makes private reinvestment impossible. At that point the nation acts like a unit, with a retained but limited private sector, surrounded by a system of universal basic income and universal basic services.

The economy is not centrally planned, but steered by real-time qualitative feedback between production units. As far as one can see, the purpose of the country’s new universal social credit system is to lay the basis for a post-wages form of social control and reward.

The great difference in Chinese transitional capitalism/proto-socialism is that it is conceived in national terms and anticipates future war — with India, Russia or the US. Hence patriotism and military expansion accompany the steady revolutionisation of production — robots, 3D printing manufacture — applied with a focused rapidity that the West cannot, at the moment, match.

If the right is scared for what this does to its pathetic fairytales of history and the West, they should be. And as the cannons and hypersonic missiles parade by, they shouldn’t be the only ones.

Here are the income shares for the US, France and China via Thomas Picketty:

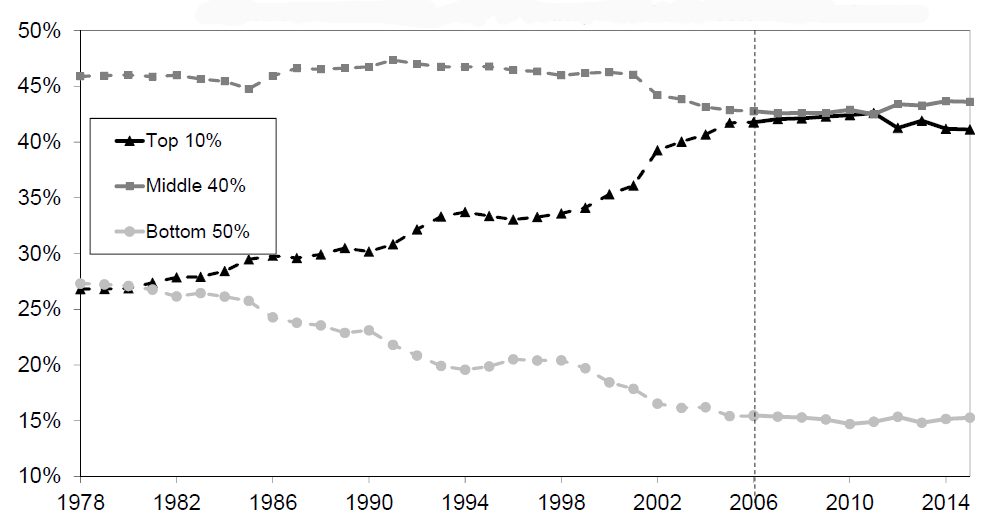

By our estimates, the share of national income earned by the top 10 per cent of the population has increased from 27 per cent in 1978 to 41 per cent in 2015, while the share earned by the bottom 50 per cent has dropped from 27 per cent to 15 per cent. The bottom 50 per cent of the population used to have about the same income share as the top 10 per cent, while their income share is now about 2.7 times lower. Over the same period, the share of income going to the middle 40 per cent has been roughly stable. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5. Income inequality in China, 1978-2015: corrected estimates

Note: Distribution of pretax national income (before taxes and transfers, except pensions and unempl. insurance) among adults. Corrected estimates combine survey, fiscal, wealth and national accounts data. Raw estimates rely only on self-reported survey data. Equal-split-adults series (income of married couples divided by two). Pre-2006 series assume that the tax/survey upgrade factor is the same as the one observed on average over the 2006-2010 period when national-level tax data exist.

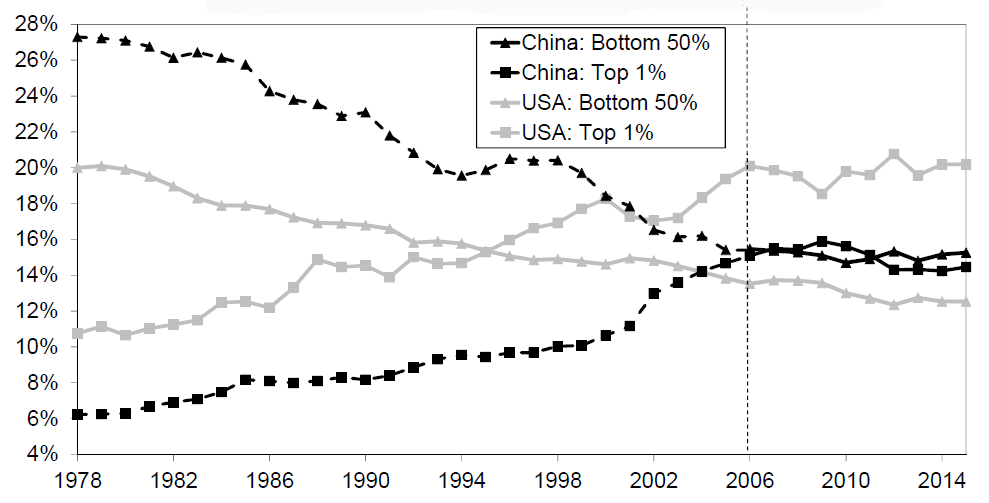

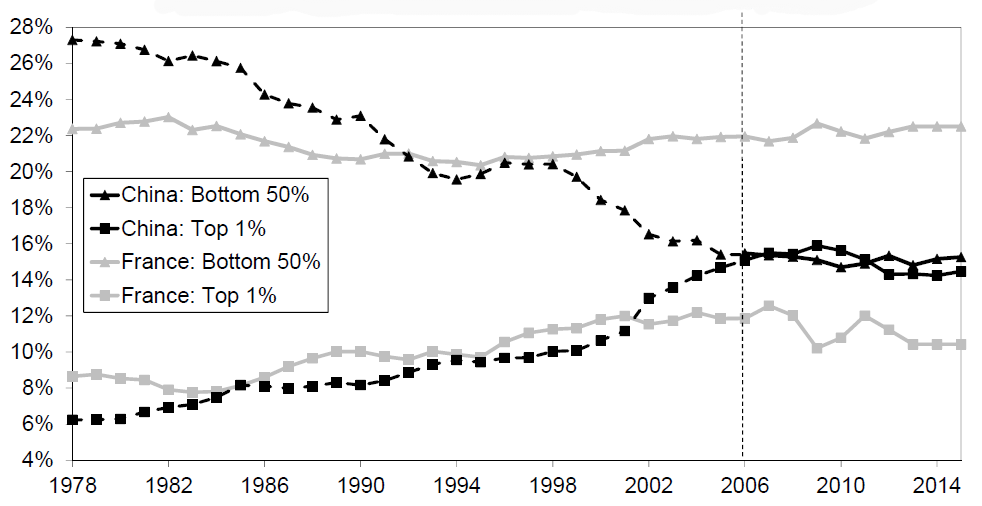

To summarise, the level of inequality in China in the late 1970s used to be less than the European average – closer to those observed in the most egalitarian Nordic countries – but they are now approaching a level that is almost comparable with the USA. In 2015 the bottom 50 per cent in China earn approximately 15 per cent of total national income versus 12 per cent in the USA and 22 per cent in France; while the top 1 per cent earns about 14 per cent of national income, versus 20 per cent in the USA and 10 per cent in France. (See Figures 6a and 6b.)

Figure 6a. Bottom 50% vs top 1% income share: China vs US

Note: Distribution of pretax national income (before taxes and transfers, except pensions and unemployment insurance) among adults. Corrected estimates (combining survey, fiscal, wealth and national accounts data). Equal-split-adults series (income of married couples divided by two).Pre-2006 series assume that the tax/survey upgrade factor is the same as the one observed on average over the 2006- 2010 period when national-level tax data exist.

Figure 6b. Bottom 50% vs top 1% income share: China vs France

Notes: Distribution of pretax national income (before taxes and transfers, except pensions and unemployment insurance) among adults. Corrected estimates (combining survey, fiscal, wealth and national accounts data). Equal-split-adults series (income of married couples divided by two). Pre-2006 series assume that the tax/survey upgrade factor is the same as the one observed on average over the 2006- 2010 period when national-level tax data exist.

It bit outmoded but the trends have continued. China is not getting fairer. It’s getting more unfair, just like Western nations.

You’ll get no argument from me that contemporary Western capitalism has lost out to oligarchy and businessomics. That’s obvious. Economic stagnation has resulted as productivity, reform, demographics and the middle classes have all stalled into under-regulation and financialisation.

But China is coming to a stop on exactly the same spot from the other end of the political spectrum. It’s not some glowing example of socialist utopia, it’s a cleptocratic mobster state. For precisely the same reason it is now entering stagnation as well, long before it is even rich.

As a result, the threat that the West will be out-spent on military capability is declining not rising. Made all the worse by China turning even further from the liberalistion path politically and economically.

Anybody with eyes can see that liberal democracy has some very large failures to address for its people. But they pale next to those confronting the people of CCP China. The comparison is preposterous.

What a shame Rundle now produces propaganda for the latter.