Australia backtracks on Indian student visas

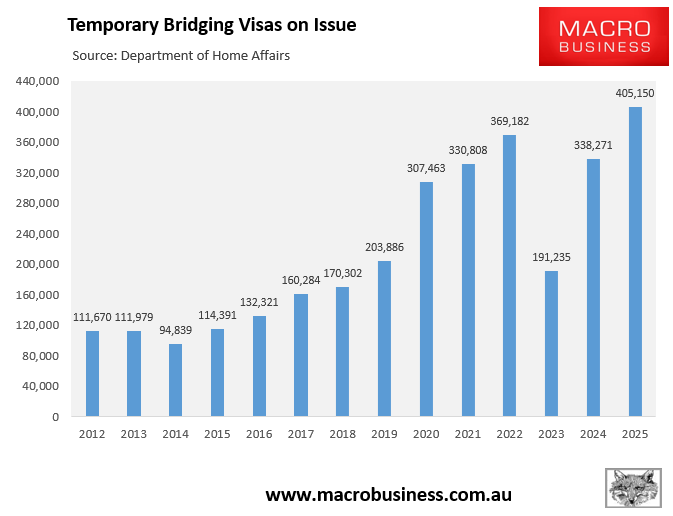

Bridging visas were the single largest contribution to the spike of temporary migrants after the Covid-19 pandemic, increasing by 201,300 between Q3 2019 and Q3 2025:

Bridging visas are generally issued by the Department of Home Affairs for two reasons:

- When the Department of Home Affairs is unable to execute an onshore visa application before the applicant’s substantive visa expires.

- The substantive visa has expired, but the migrant has yet to leave.

Abul Rizvi, a former senior bureaucrat in the immigration department, previously stated that bridging visas are “the most important barometer of the health of the visa system” and argued that the blowout in bridging visas is evidence of “administrative incompetence”.

The Administrative Review Tribunal (ART) is experiencing an “unprecedented surge” in appeals over student visa refusals, which is partly behind the blowout of bridging visas.

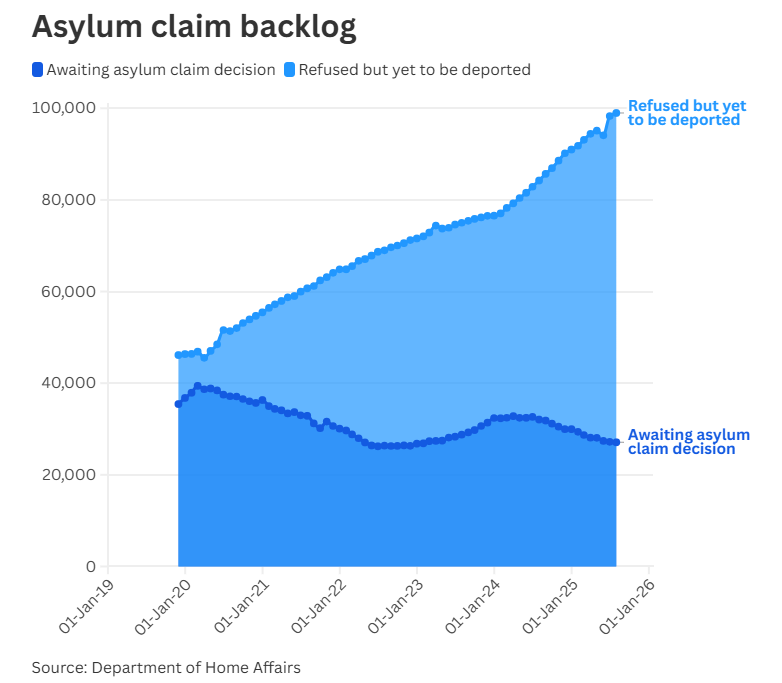

Frank Chung of News.com.au recently published a concerning report detailing the massive increase in migrants attempting to claim asylum.

Abul Rizvi told Chung that “there’s an increasing number of student visa holders applying for asylum”, which risks creating a “massive underclass” that could negatively impact “social cohesion”.

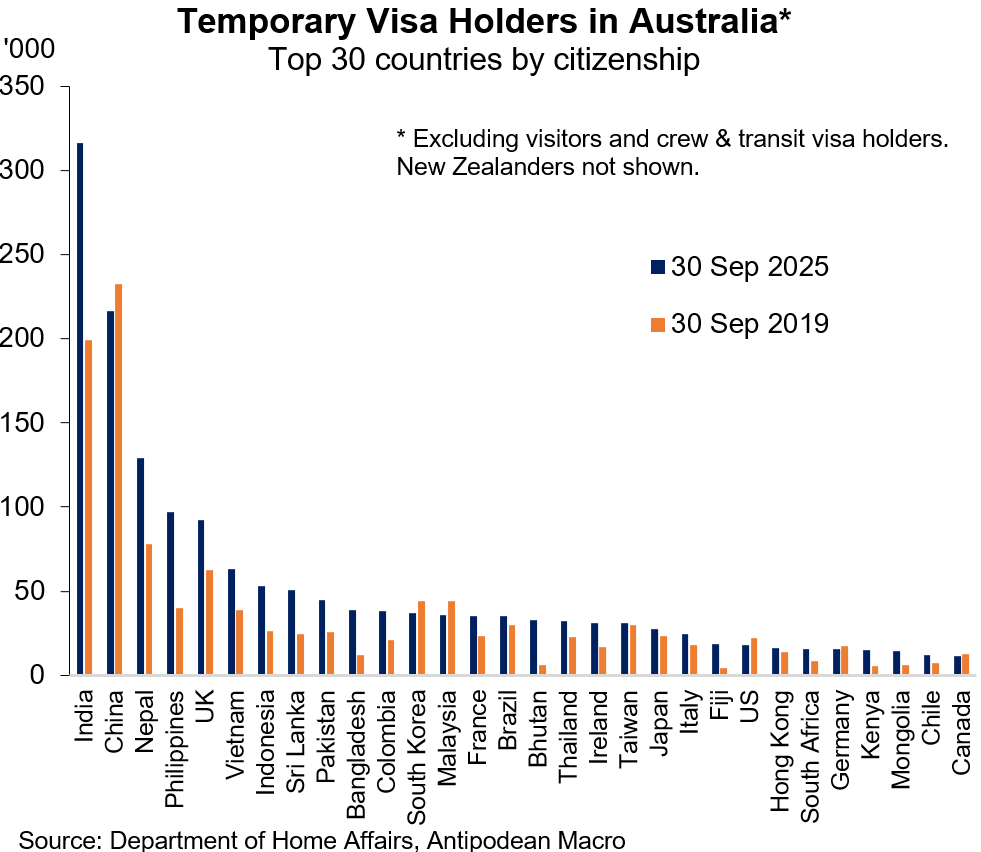

The surge in temporary migration and bridging visas is being driven by Indians.

As illustrated below by Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro, “Indian citizens in Australia held the most temporary visas by far, followed by Chinese citizens (who were #1 six years prior). (This analysis excludes NZ citizens.)”:

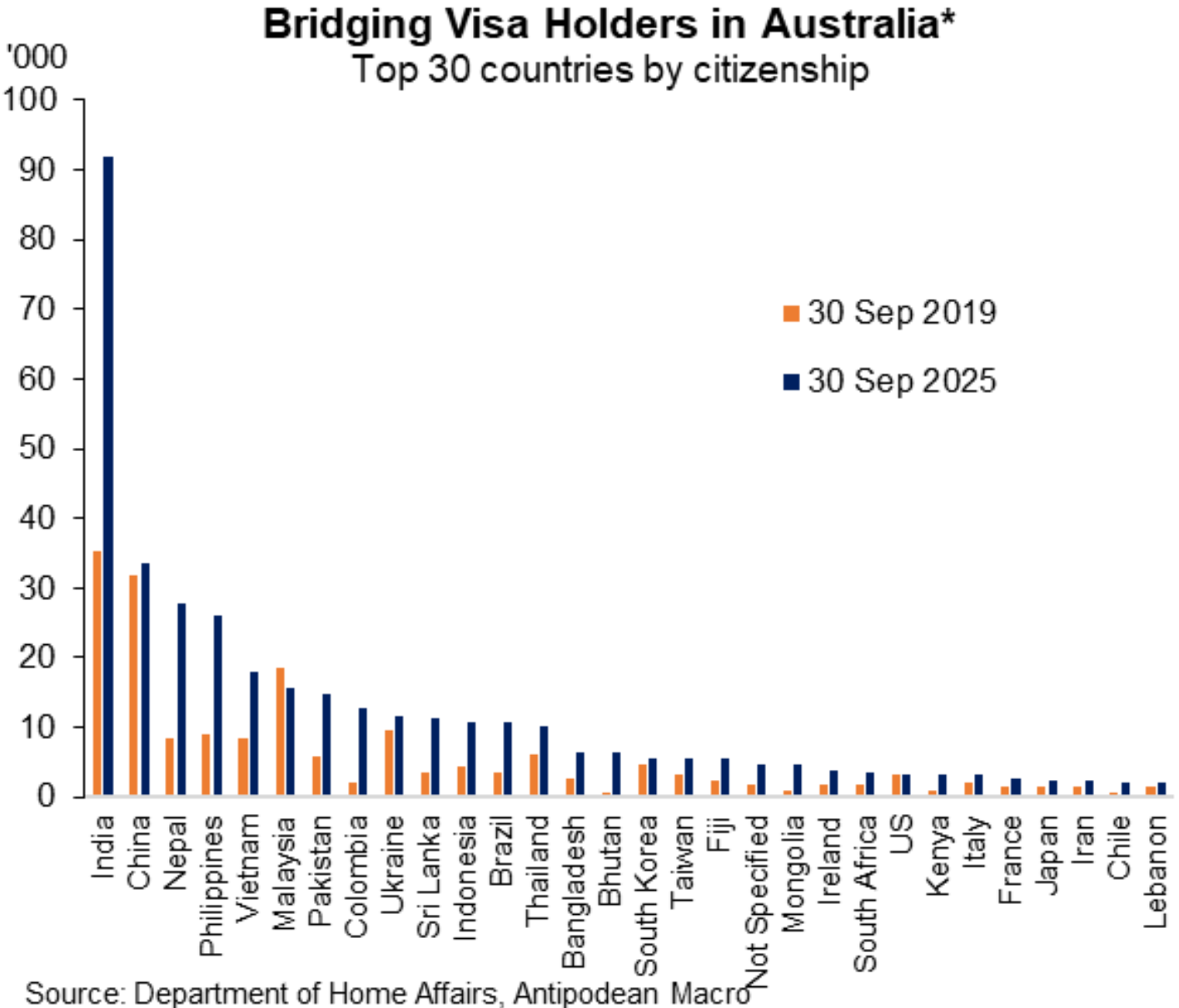

Indians have also contributed most to the growth in bridging visas, dwarfing every other source country:

Amid concerns of widespread rorting of the visa system by non-genuine students, the former Morrison Coalition government in 2019 deemed students from India, Nepal, and Pakistan “high-risk”. This meant that they faced tighter scrutiny when applying for visas from the Department of Home Affairs.

Consequently, several Australian educational institutions ceased to accept student applications from India.

However, the Australian government has also signed three migration-related agreements that have made it easier for Indians to live and work in Australia. These pacts are:

- The Australia-India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement (ECTA), signed by the former Morrison Coalition government late in its last term, which made it easier for Indians to live and work in Australia.

- The Australia-India Migration and Mobility Partnership Agreement, signed by the Albanese government in its first term.

- The Mechanism for Mutual Recognition of Qualifications, signed by the Albanese government in its first term.

As a result, Indian students and temporary visa numbers soared to record levels in the post-pandemic period.

Last year, the Albanese government lowered India’s student‑visa risk rating to support universities and bolster student flows. Countries like Bhutan, Vietnam, and Nepal also saw their risk weightings lowered.

The easing of risk weightings was in response to pressure from universities, who were pushing for easier visa processing. The government also wanted to maintain Australia’s competitiveness against Canada and the UK.

However, following integrity concerns, including a sharp rise in fraudulent financial documents and unverifiable academic records, the Albanese government has reversed course and retightened risk weightings to the highest‑risk Evidence Level 3 category.

Visa consultants in Bengaluru reported a noticeable increase in the submission of fake or unverifiable financial documents for student visa applications.

Officers have reportedly struggled to authenticate marksheets and certificates issued by certain institutions, prompting concerns about the reliability of the documents.

Multiple reports indicated a pattern of non‑genuine applicants using the student‑visa pathway for work migration rather than study.

The policy change is also likely a response to fake degree busts in India.

A major operation by Kerala Police uncovered a fake degree racket that produced and distributed over 100,000 counterfeit university certificates linked to 22 universities.

This operation has been ongoing for years, with estimates suggesting that more than one million fake degrees have been circulated across India, affecting students seeking employment and educational opportunities both domestically and abroad.

The change in risk weighting to Level 3 means that applicants from India, Bhutan, Vietnam, and Nepal now face stricter documentation requirements, deeper financial scrutiny, and longer processing times.

Jobs & Skills Australia’s (JSA) latest report on the international education system noted that most international students come to Australia primarily to work and live, rather than for educational purposes.

“Nearly 70% of international higher education students reported that the possibility to migrate was a reason for choosing to study in Australia, rising to 77% of Indian and 79% of Nepali higher education students”, JSA reported.

Moreover, JSA noted that over 90% of Indian and nearly 96% of Nepali higher education students cited the ability to work while studying as one of the reasons they chose Australia. “80% of students from South and Central Asia (including India and Nepal) were working during study”, JSA said.

The Takeaway:

The Albanese government erred badly when it initially lowered the risk weighting for India and other nations to Level 2.

Given the widespread history of rorting, it made no sense to open the student-migration pathway even wider, thereby increasing the number of people seeking to live and work in Australia.

The move back to the Level 3 risk weighting is an acknowledgement of this error and a much-needed course correction.