Macquarie rings the bell on data centres

In the long history of financial markets, there have been all manner of hot assets; in the Netherlands in the 1630s, it was tulip bulbs, in the 1720s Britain, it was shares in the South Sea Company, and today the hottest asset on the market is anything to do with AI.

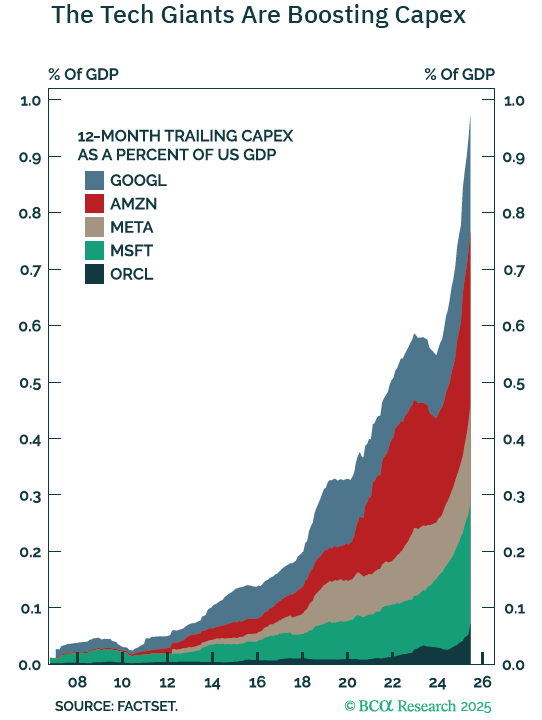

In the United States, the investment of the five largest contributors to tech-sector capital expenditure (Google, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, and Oracle) now accounts for almost 1% of U.S. GDP.

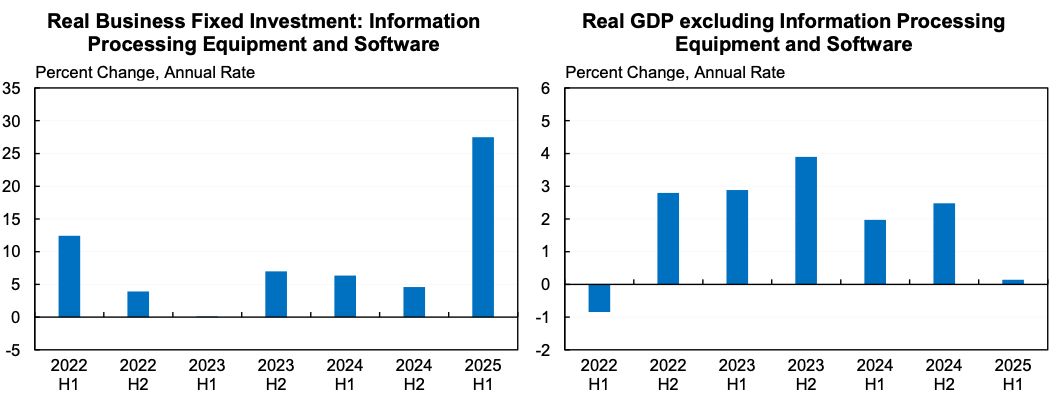

According to the estimates of Harvard University economist Jason Furman, in the first half of 2025 the U.S. economy grew by just 0.1% after excluding the impact of information processing equipment and software.

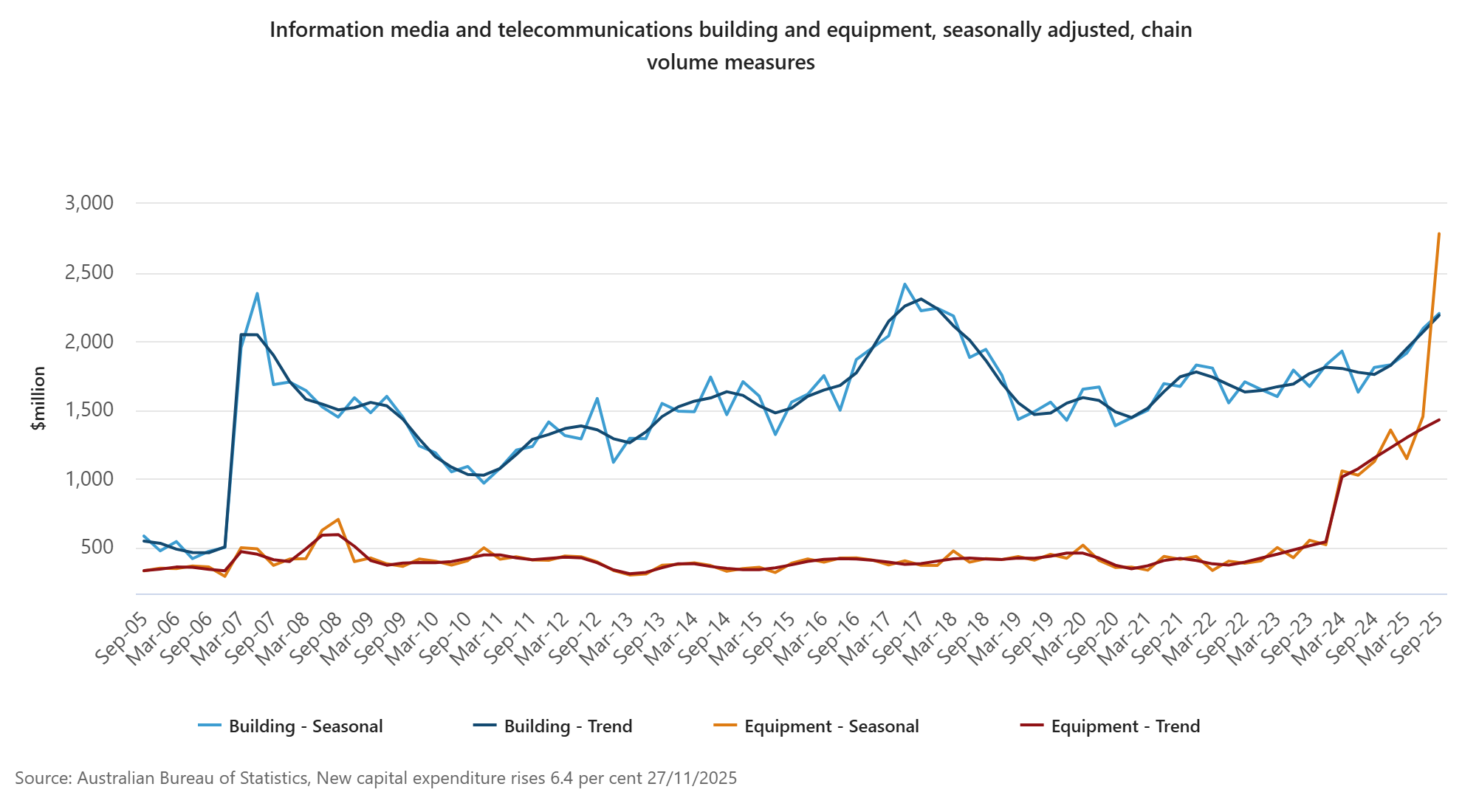

Meanwhile, in Australia, the most recent national accounts saw a dramatic surge in investment in data centre equipment, accounting for a large majority of the net surge in private sector activity seen during the September quarter.

But as investment in AI and data centres surges across the globe, the Macquarie Group is currently exiting its investments in data centres in swift succession.

Macquarie’s infrastructure investment arm was part of a $23.5 billion sale of an Australian data centre company to Blackstone in September 2024.

In October, Macquarie inked a deal for the sale of Aligned Data Centre in a $US40 billion deal to a consortium led by BlackRock’s Global Infrastructure Partners.

Macquarie is also currently taking bids on a $1.5 billion stake in its Netherlands-based data centre assets.

It may be that Macquarie is playing a similar role as Sir Isaac Newton played in the South Sea Bubble, selling out early for a handsome profit.

Where Newton later went wrong was piling back, as the mania reached even greater heights and he lost most of his money.

The big question is, what sort of investment and asset price cycle is this?

Is it a rerun of the South Sea Bubble, where investors were chasing returns based on a dream and were ultimately disappointed when it dramatically did not realise its promise?

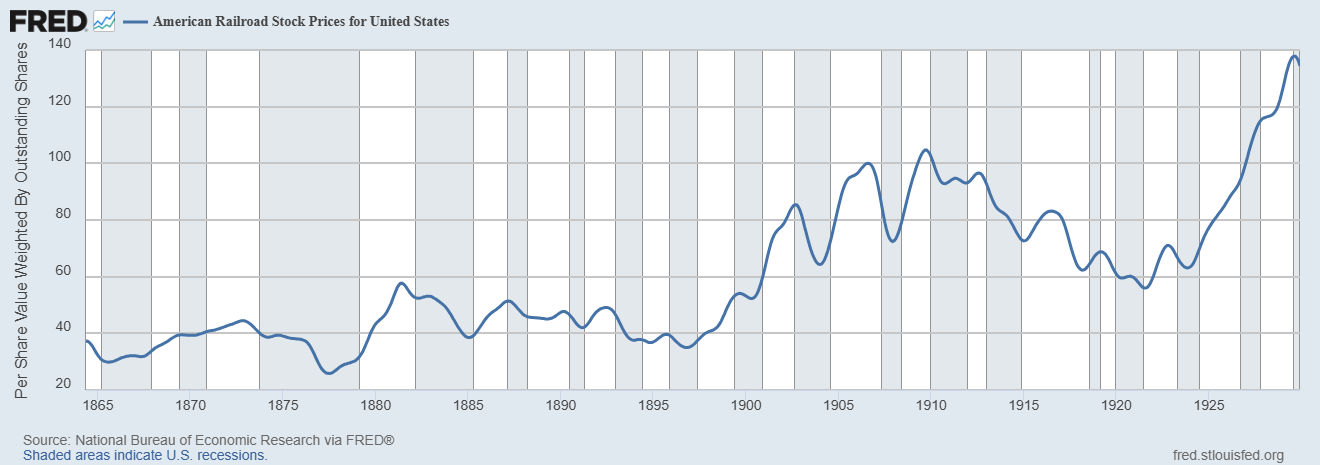

Or is it more akin to the railroad investment booms of the 19th century, which ultimately transformed the nature of the world?

The problem for investors is AI may well prove transformative, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it will be profitable.

During the railroad rush of the latter third of the 19th century in the United States, if an investor put their life savings into railroad stocks in 1864, over three decades later the capital value of their investment was the same.

This metric is also an example of survivorship bias, with dozens of major railroad companies going bust during this time.

Meanwhile, the latest Bank of America fund manager survey reveals that investors are more bullish on stocks today than they have been at any point in the last three and a half years and are holding the smallest proportion of their portfolios in cash on record.

In the end, AI and the accompanying markets are priced for near perfection.

Oftentimes this sort of sentiment sets up a challenging rendezvous with reality. But even some of the best investors in the world have struggled to pick where this story ends.