Former Labor leader Bill Shorten warned that Australia’s declining economic complexity is the single biggest threat to national security.

Shorten noted that the Harvard Kennedy School’s Economic Complexity Index ranked Australia 105th out of 145 nations.

“Our near neighbours are Botswana, Panama, Namibia and Togo”, he said.

“This is not an academic curiosity; it is our central strategic problem. We have become a nation with a world-class campus but no factories: a quarry but no forge”.

“Australia’s economic structural fragility is “the single greatest threat to our long-term security”, he said.

Shorten is now the vice chancellor of Canberra University and urged Australia to create a system of specialist universities to nurture the innovation necessary to build a more resilient and complex economy.

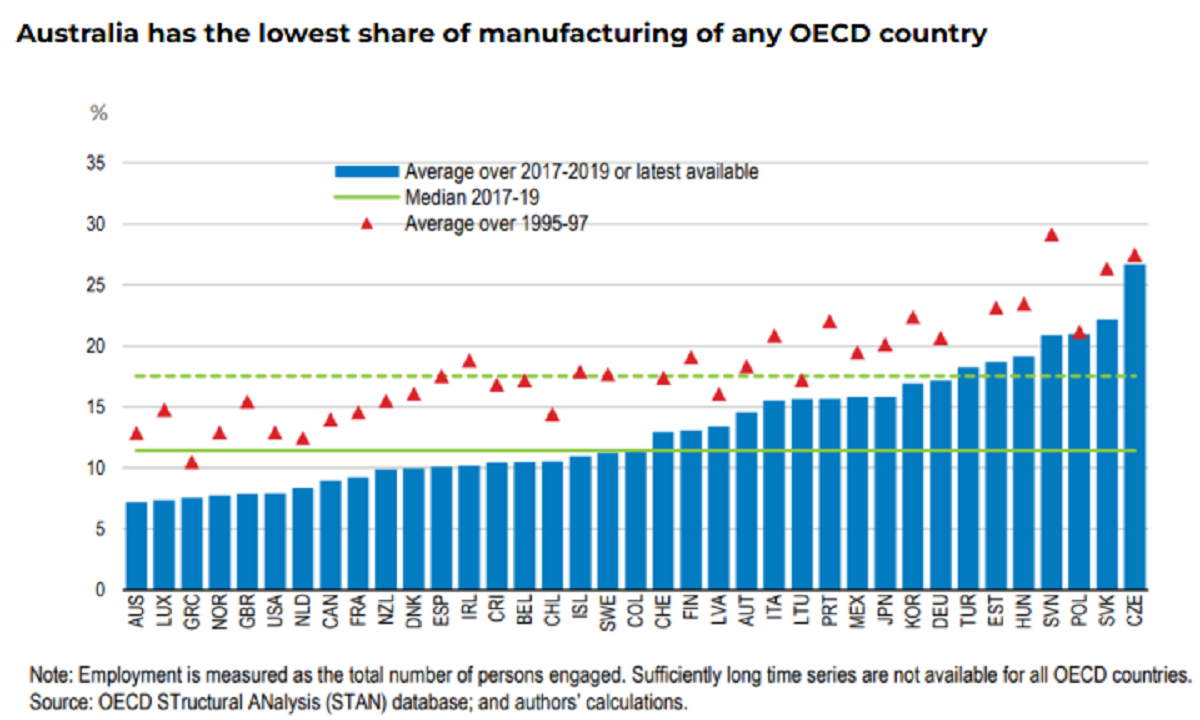

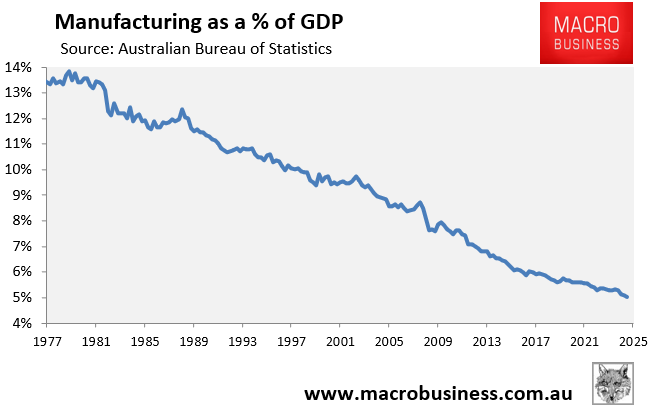

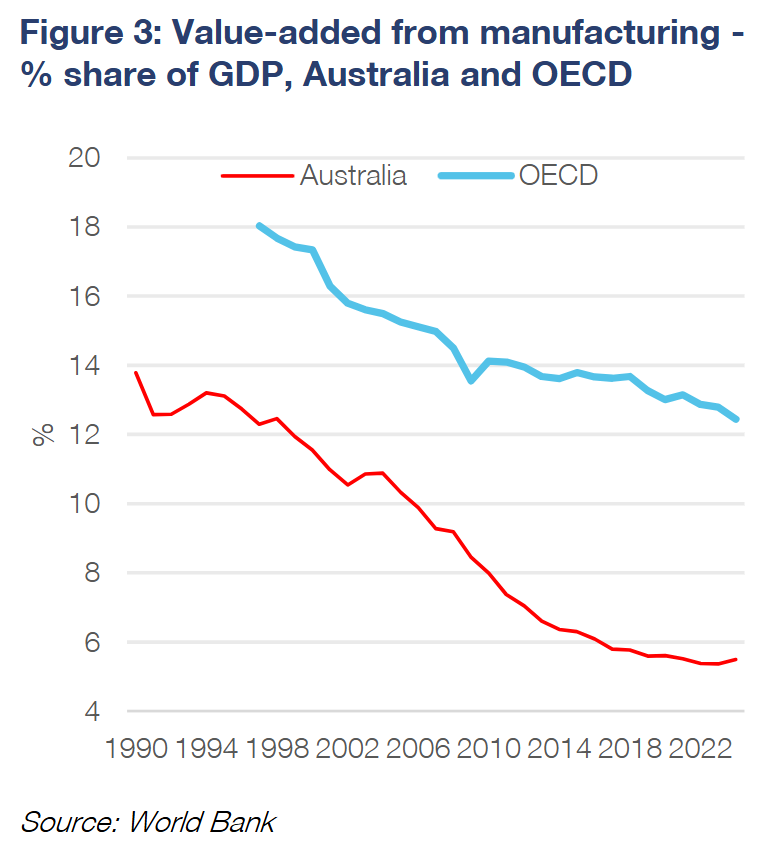

A significant reason why the Australian economy has become less complex is the collapse in the manufacturing sector, which is now the smallest in the OECD as a share of the economy.

In Q2 2025, manufacturing’s percentage of GDP decreased to a record low of 5.0%, down from 8.9% two decades ago and 15% in the mid-1970s.

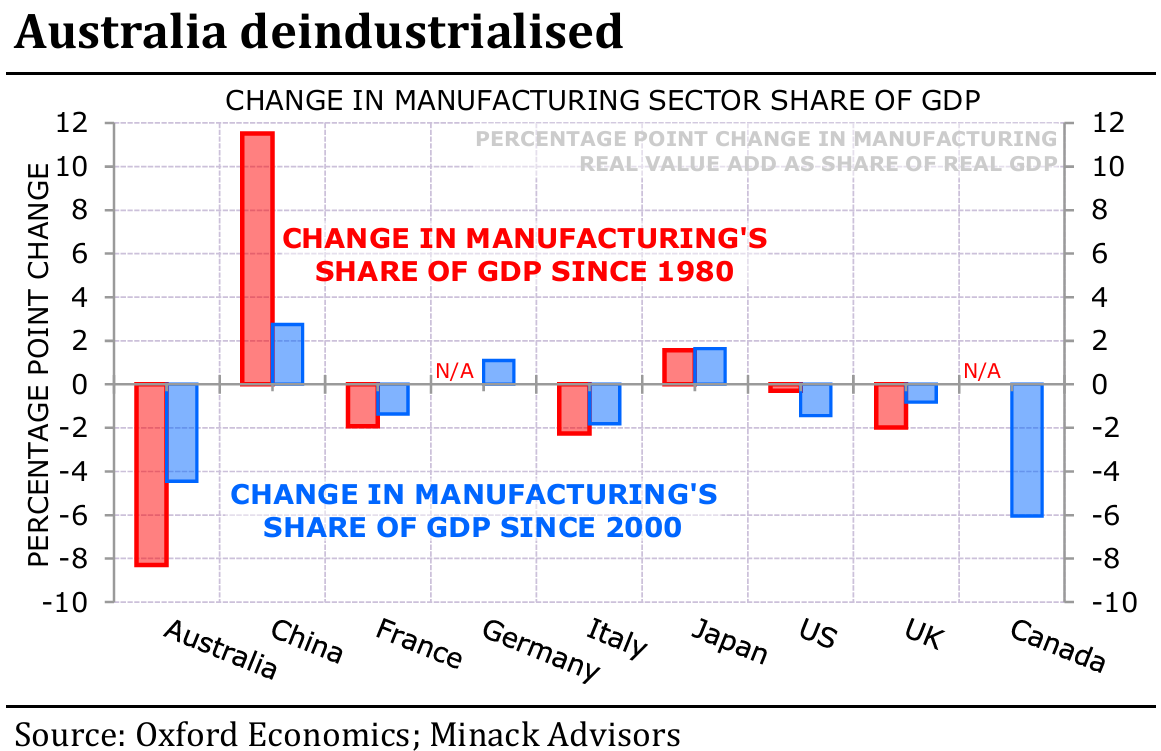

A recent report from leading independent economist Gerard Minack showed how Australia has suffered an abnormally large decline in manufacturing relative to GDP since 1980 and 2000:

Any further contraction in manufacturing will deindustrialise the economy further, lessening its diversity and complexity and making Australia less self-sufficient.

The reality is that Australia’s manufacturing sector has no future as long as energy prices rise and reliability deteriorates.

As Vivek Dhar from the Commonwealth Bank of Australia shows below, “the decline in the share of manufacturing in Australia’s economy has been faster than advanced economies, reflecting the overall challenges of keeping labour, materials, and energy prices low enough for Australia’s manufacturing sector to remain competitive”.

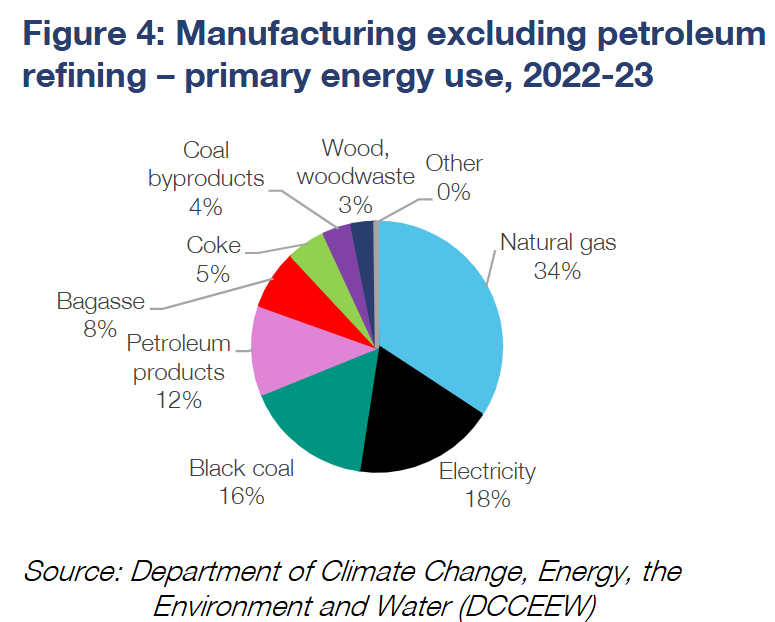

“Manufacturing, excluding the petroleum refining sector, primarily uses natural gas for its energy consumption”, noted Dhar. “Electricity is the second largest energy source, followed by black coal, petroleum products and then more fossil fuels”.

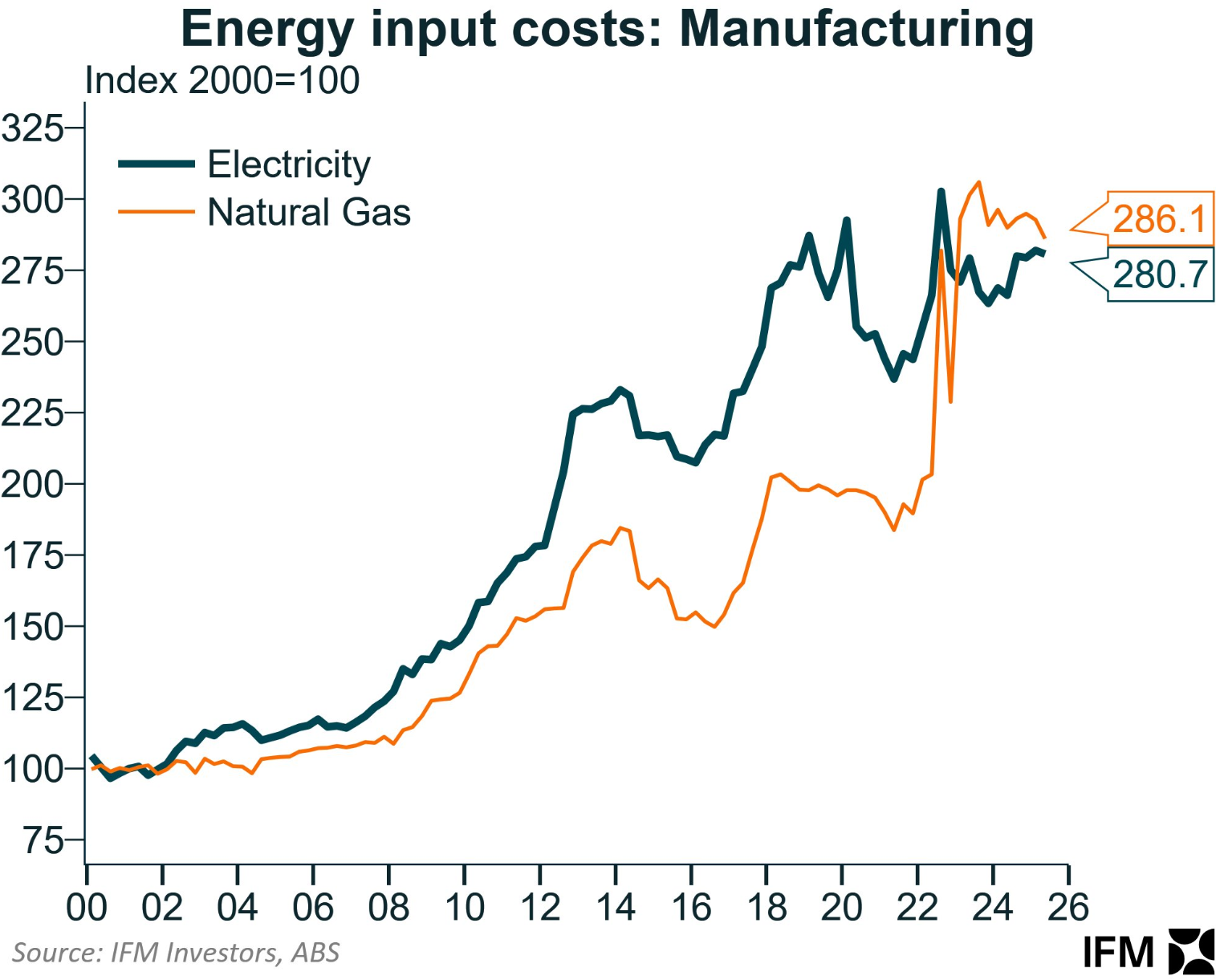

Alex Joiner, chief economist at IFM Investors, illustrates the manufacturing sector’s energy problem:

Natural gas input costs in industry have risen by 186% since 2000, while electricity prices have increased by 181%.

The rise in natural gas costs has been especially dramatic since 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine.

ASIC insolvency figures show that over 1400 manufacturers nationwide have failed since 2022-23.

Among these, Incitec Pivot, a large fertiliser company, closed its Australian operations due to rising energy costs.

Qenos, Australia’s last major plastics manufacturer, shut down in 2024 due to high energy prices, leaving the country entirely reliant on polymers imported from China.

Oceania Glass, Australia’s lone architectural glass manufacturer, closed in February 2025 after 169 years of operation due to rising energy costs and Chinese dumping.

Orica, the world’s largest producer of mining explosives, chemicals, and agricultural fertilisers, and BlueScope Steel have threatened to downsize their Australian operations and relocate to the United States in response to rising energy prices.

The reality is that without affordable and reliable gas and electricity, Australia’s manufacturing industry will continue to shrink, the country will deindustrialise, and the economy will become less diverse.

Unfortunately, energy prices in Australia will continue to rise.

The refusal of East Coast Australia to implement a domestic gas reservation plan is a major contributor to rising energy prices.

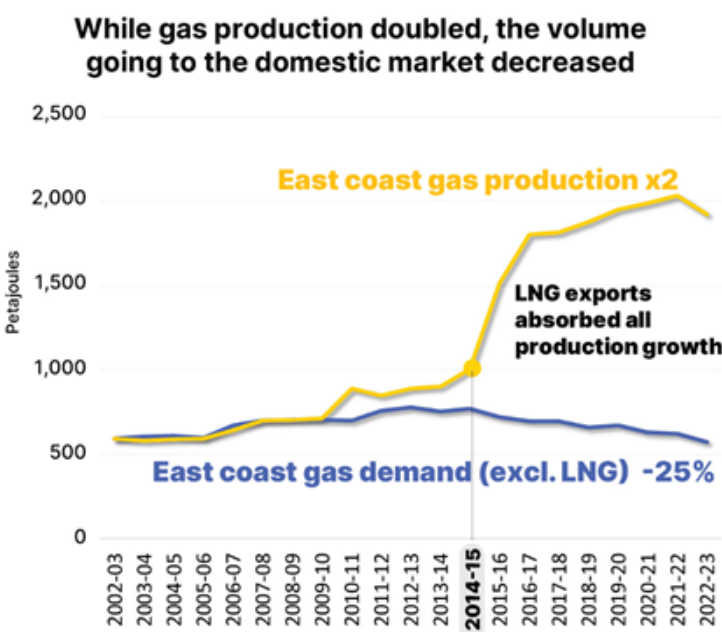

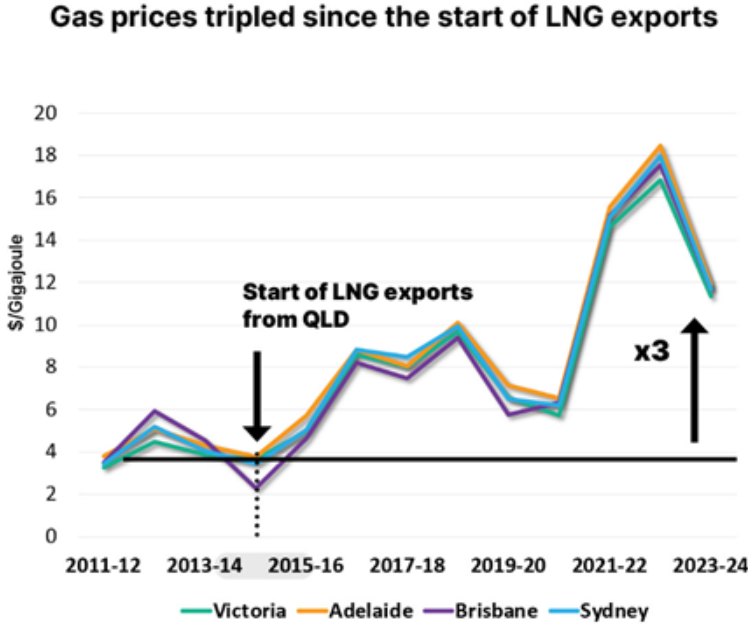

In 2015, the East Coast began exporting natural gas from Gladstone. Since then, the East Coast’s gas output has doubled while providing 25% less gas to the domestic market.

As a result, an artificial gas shortage has emerged, increasing East Coast gas prices to approximately $12 per gigajoule.

East Coast Australia now has the highest gas prices of any exporting jurisdiction in the world. These high gas costs have contributed to rising power prices, as gas is a significant marginal price setter in the wholesale market.

The situation will further worsen if the East Coast begins importing gas into New South Wales, Victoria, and possibly South Australia to alleviate domestic gas shortages.

Once liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports commence, East Coast gas prices will rise to import-parity levels of roughly $20 per gigajoule, raising energy costs.

Implementing a domestic reserve on the East Coast is critical to lowering prices and avoiding the negative consequences of LNG imports.

Second, Australia’s pursuit of ‘net zero’ and the shutdown of baseload coal facilities will drive up electricity prices.

Creating a diffuse network of renewable energy sources, transmission, and storage will cost hundreds of billions of dollars, which will eventually be reflected in higher power bills and taxes to finance subsidies.

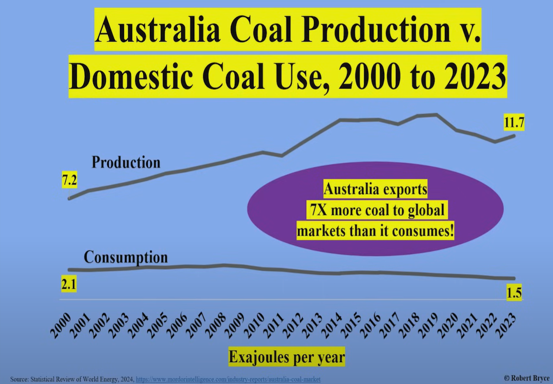

Australia leads the world in coal exports and ranks second in natural gas exports. We export around seven times more coal than we consume as a country, as well as four times more gas.

Australia also has the world’s largest uranium deposits.

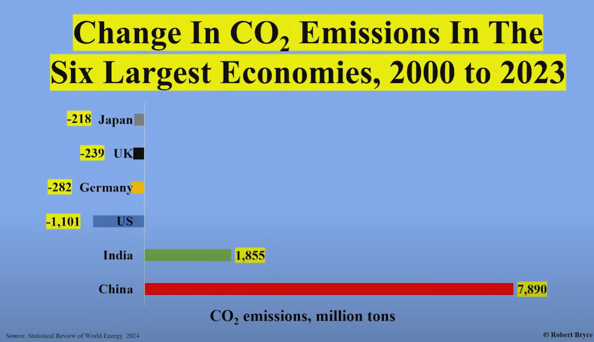

Australia should, therefore, have some of the world’s cheapest gas and electricity. Instead, it has chosen to deny itself access to these resources while exporting energy security to Asia, particularly China and India, which are driving the rise in global emissions.

Our energy policy failures will negatively impact all Australians, but the energy-dependent industrial sector will bear the brunt.

Australia will become an industrial wasteland, with a less diverse and sophisticated economy, lower productivity, and, ultimately, lower living standards.