China and India rush headlong into coal

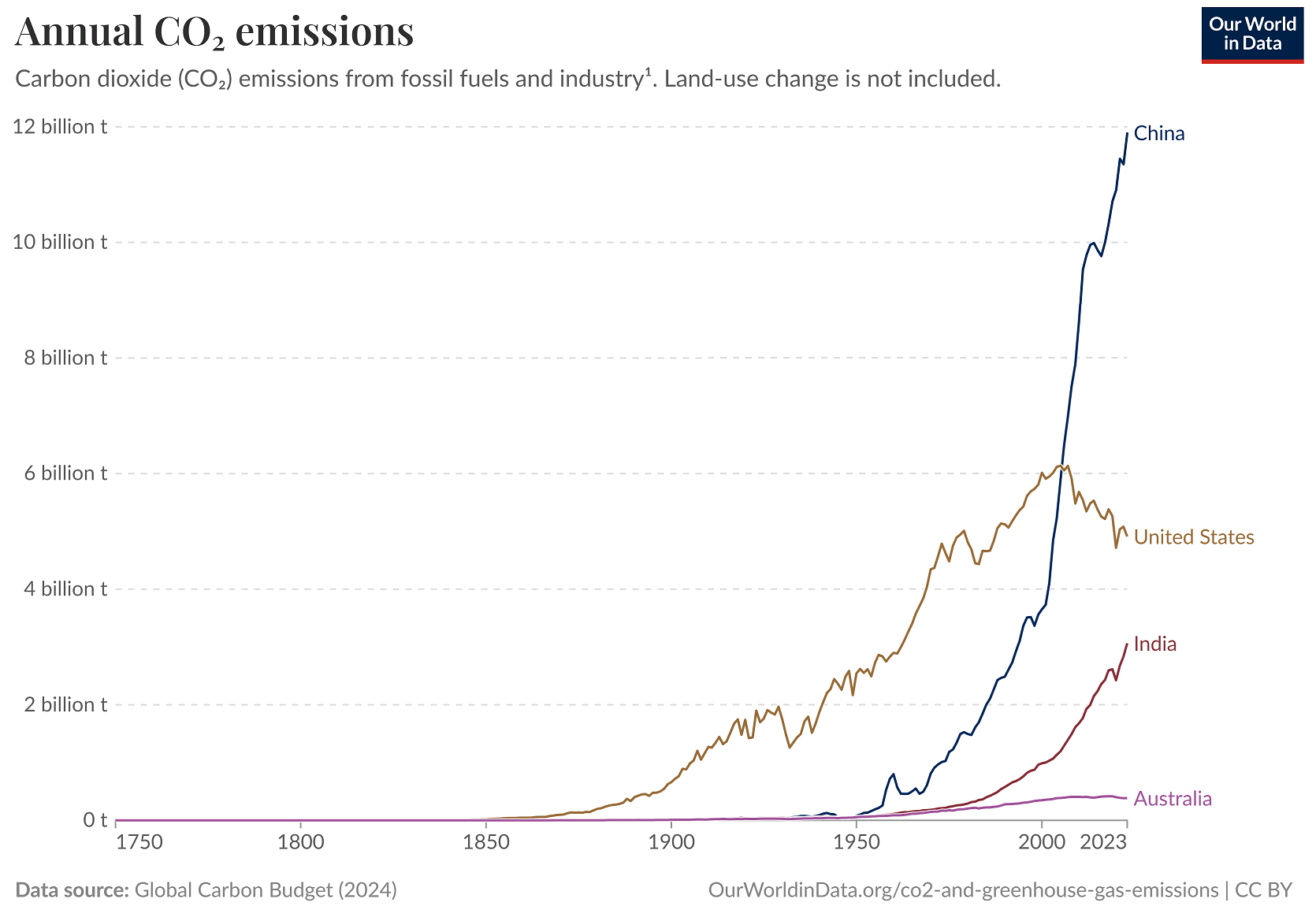

China (31.5% share in 2023) and India (8.1% share in 2023) have driven the increase in global carbon emissions this century.

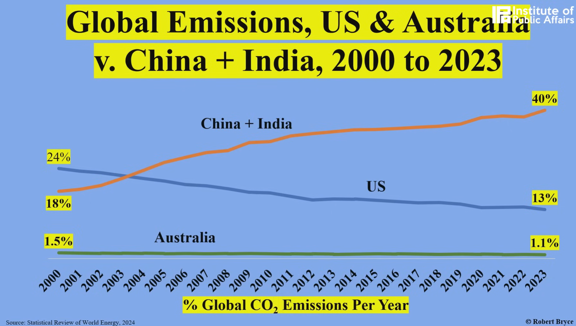

As illustrated below by US energy expert Robert Bryce, China and India’s combined share of the world’s carbon emissions rose from 18% in 2000 to 40% in 2023.

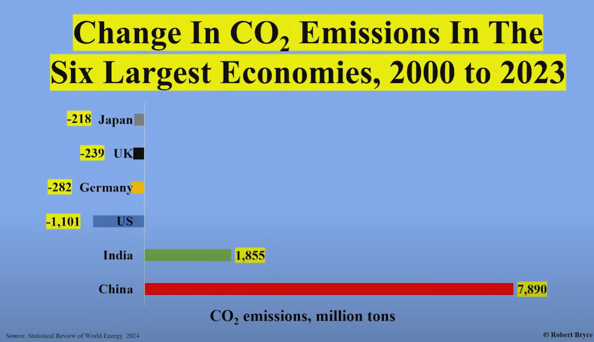

While the developed world has decarbonised, China and India have pumped enormous volumes of CO2 into the atmosphere.

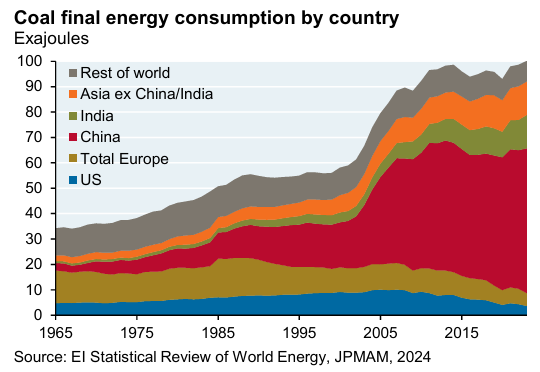

A key driver of the rise in China’s and India’s emissions is their insatiable appetite for coal.

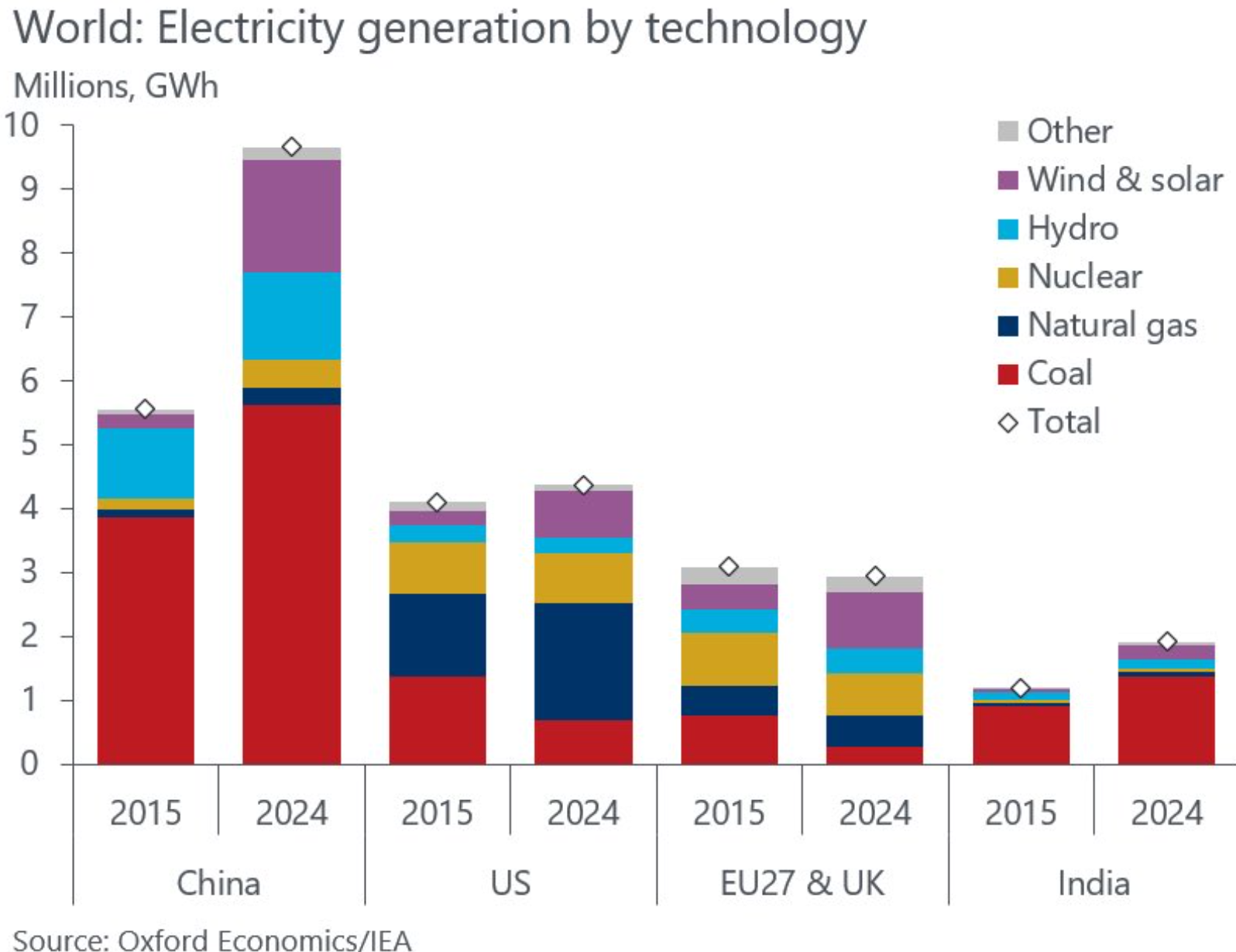

The chart below from Oxford Economics shows the various sources of electricity generation across major economies.

While the developed world has moved away from coal over the last decade, China and India have increased their coal consumption.

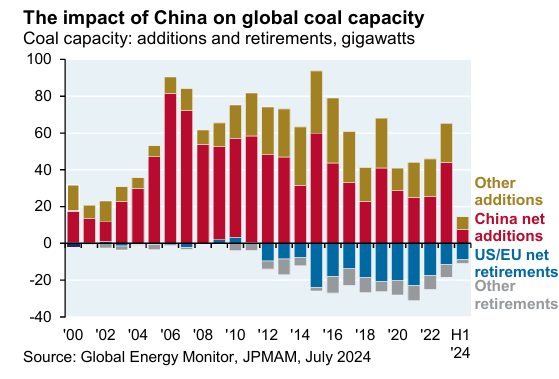

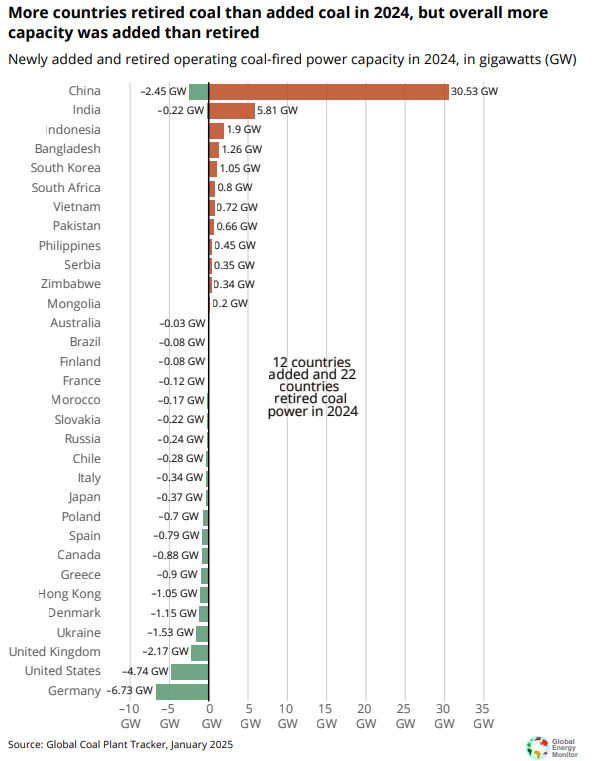

Both nations have added more coal-fired generation than the rest of the world has decommissioned.

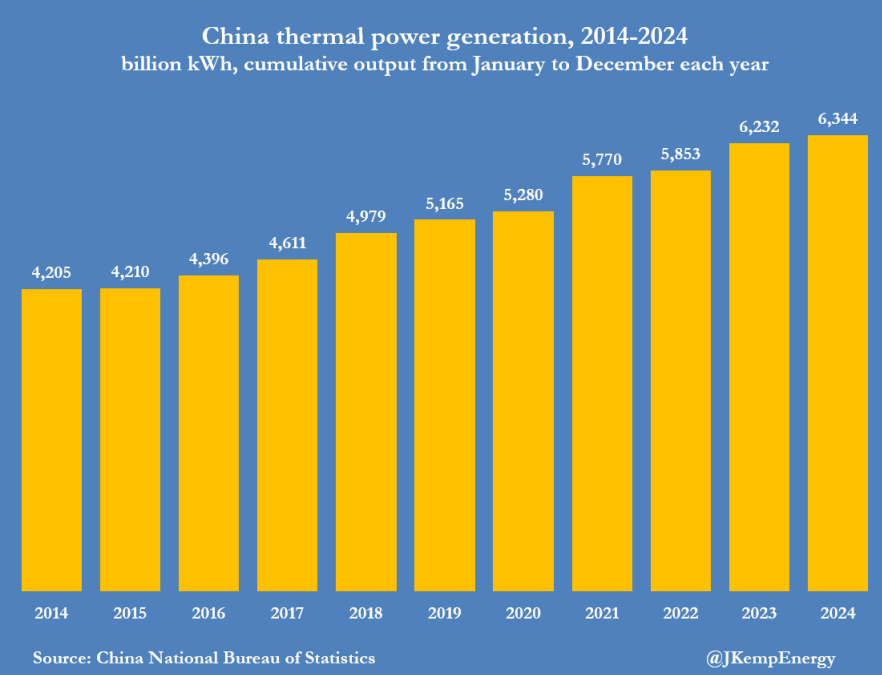

In the decade to 2024, China’s thermal coal electricity generation increased by 51%. Chinese coal production, imports, and consumption all reached new highs.

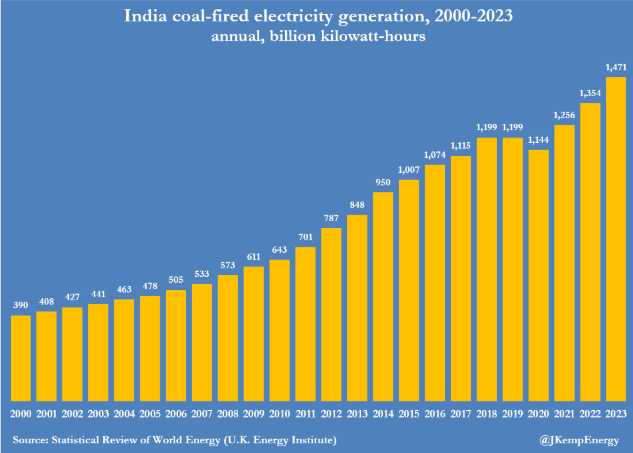

India’s coal consumption has surged by more than 70% over the past decade.

The trends are clear: the developing world, particularly China and India, continues to add to coal-fired capacity, while the developed world continues to close coal-fired power stations.

The situation is likely to continue for the foreseeable future.

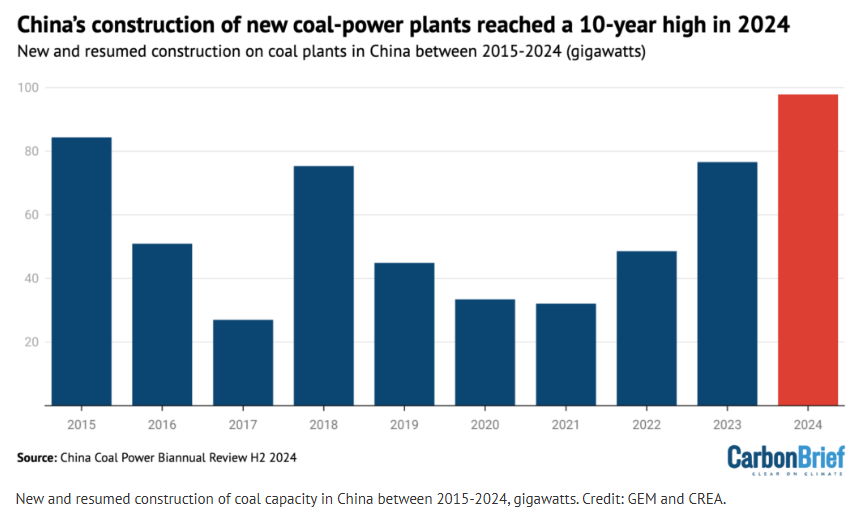

Recent research from the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) and Global Energy Monitor (GEM) showed that China began construction of 94.5 gigawatts (GW) of new coal-power capacity and resumed 3.3GW of halted projects in 2024. This represented the highest level of construction in the last decade.

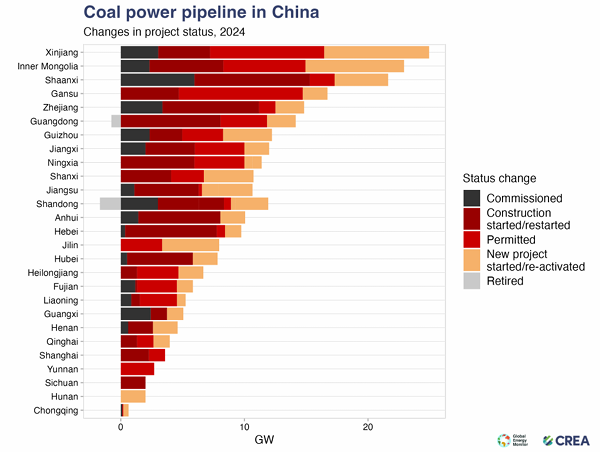

CREA also showed that the pipeline of Chinese coal power projects expanded.

China and India are rapidly expanding their coal capacity, as detailed in the latest Global Energy Monitor (GEM) briefing:

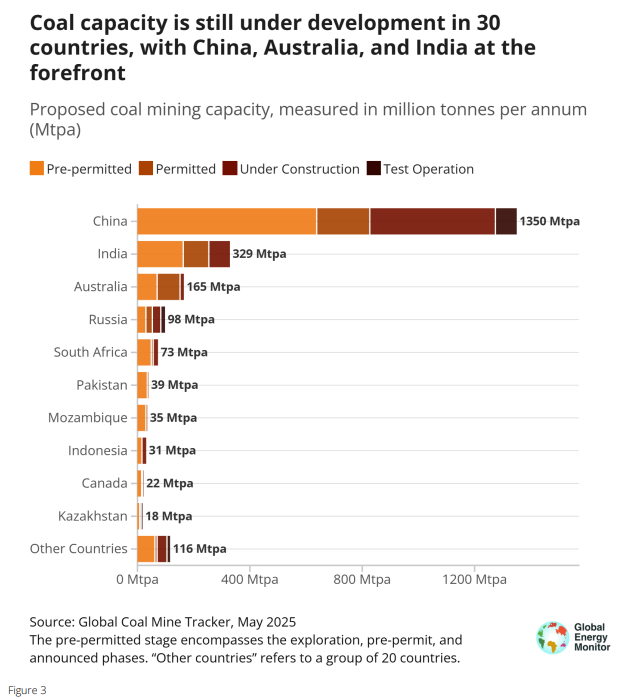

An estimated 2,270 Mtpa of new coal mining capacity remains under development…which represents a quarter of 2024 global production (8,770 Mtpa).

Nearly 90% of this proposed capacity is located within just a few countries. China leads by a wide margin, accounting for 1,350 Mtpa of proposed capacity, accounting for 60% of the global proposed capacity… Of this amount, 39% is already under construction or in test operation, 14% has been approved, and the remaining 47% is in early planning, awaiting approval…

This amount surpasses the combined operating coal capacity of Indonesia and Australia, the world’s third- and fourth-largest coal producers…

India follows with 329 Mtpa, nearly half of which is being developed by state-owned Coal India”…

Three-quarters of mine proposals are “greenfield” developments (1,696 Mtpa), signaling the coal industry’s willingness to break ground on new mines that tend to lock in more long-term production…

Coal production in India has risen steadily, reaching a record 1,048 Mt in FY 2024–25. This growth is expected to continue as the government pushes to boost domestic output, aiming to reduce import reliance and allegedly improve energy security.

The government targets 1.3 billion tonnes of coal production by FY 2027 and 1.5 billion tonnes by 2030. To support this goal, India plans to open 100 new coal mines, adding 500 Mtpa in capacity by 2030. Over 80 Mtpa is expected to come online in FY 2025–26, suggesting that already permitted or under-construction projects could be fast-tracked…

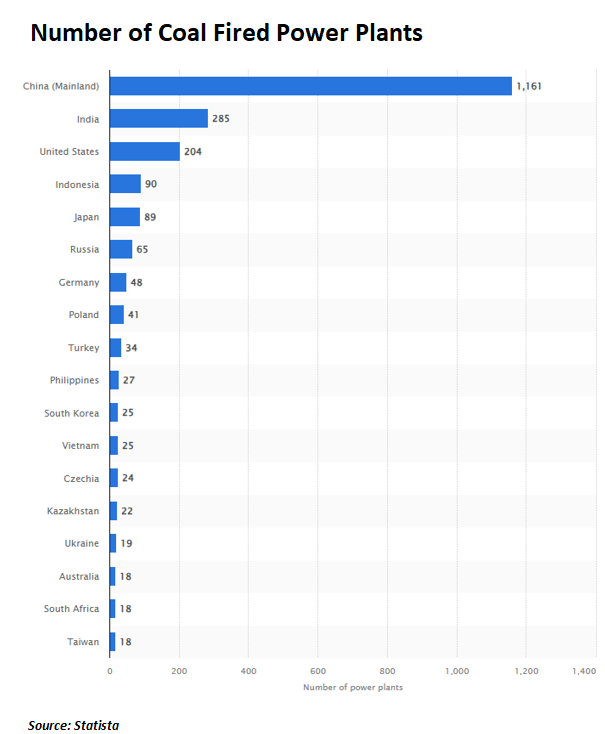

According to Statista, China (1,161) and India (285) have the world’s highest number of coal-powered generators, which are still growing in number. Australia has only 18 coal generators in operation, which are slated for closure.

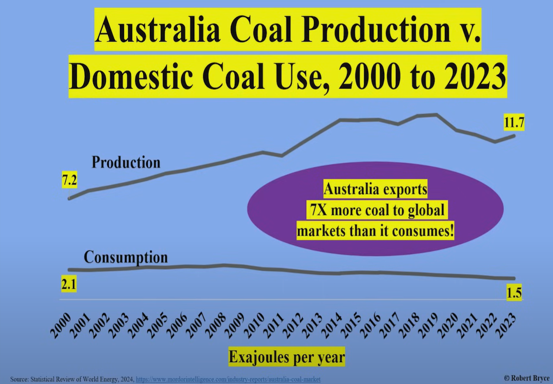

Australia exports seven times more coal than it uses. A large chunk of these coal exports are to China and India.

Meanwhile, as noted above by the GEM briefing, China’s proposed coal additions “surpasses the combined operating coal capacity of Indonesia and Australia, the world’s third- and fourth-largest coal producers”.

Instead of committing energy suicide in the futile pursuit of ‘net zero’, Australia can provide itself with affordable and dependable energy by expanding coal-fired generation and burning a bit more coal at home while exporting a little less.

Global carbon emissions would be unchanged, and our economy and living standards would not plummet due to unreliable and expensive energy.