Canada’s economic collapse an omen for Australia

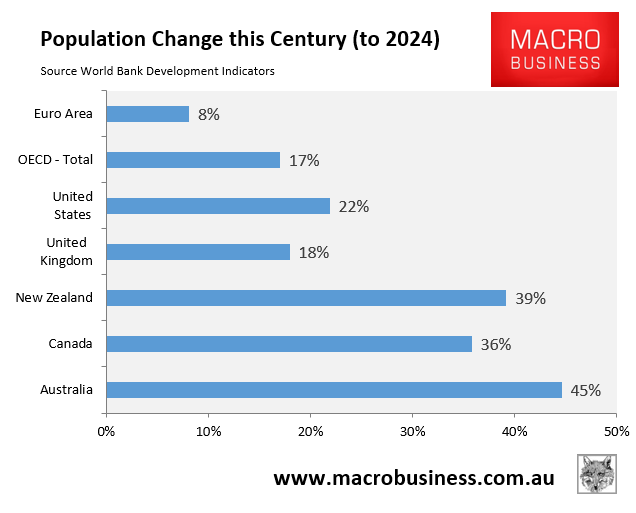

Out of all nations on earth, Canada is arguably the most similar to Australia.

Both nations are resource-rich, hosting relatively small populations on massive landmasses.

The overwhelming majority of the population lives in small pockets where the weather is most favourable. The bulk of Australia’s population lives on the East Coast, whereas the bulk of Canada’s population lives in the south near the US border.

Both nations have highly concentrated oligopolistic banking systems, and both use the Westminster system of government, inherited from the British.

Finally, both national governments have run high immigration policies, which have aggressively grown their respective populations (alongside New Zealand).

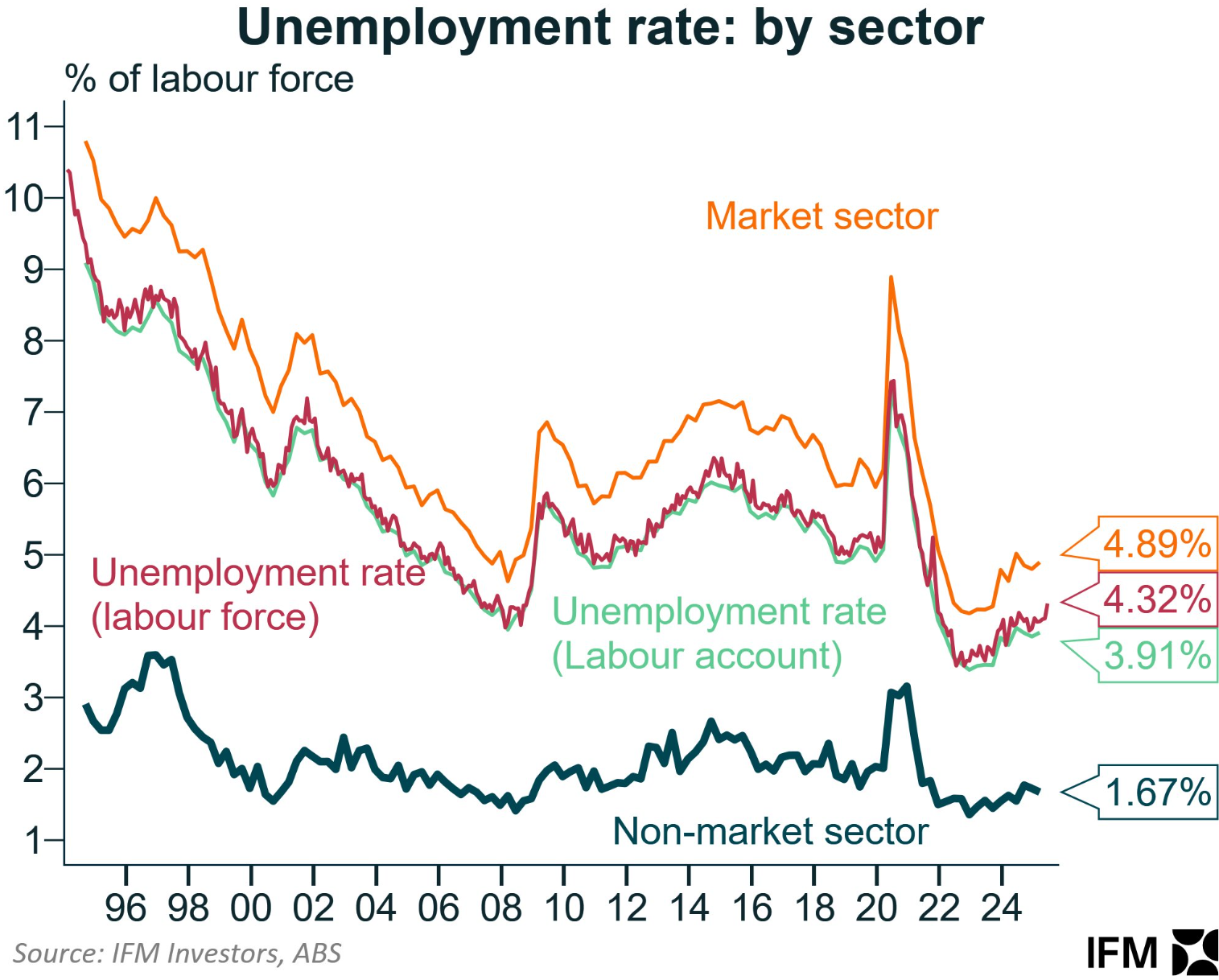

Australia is currently enjoying an unemployment rate that is among the lowest in the advanced world at 4.3%. This low unemployment rate has been driven by an unprecedented boom in non-market (government-aligned) jobs.

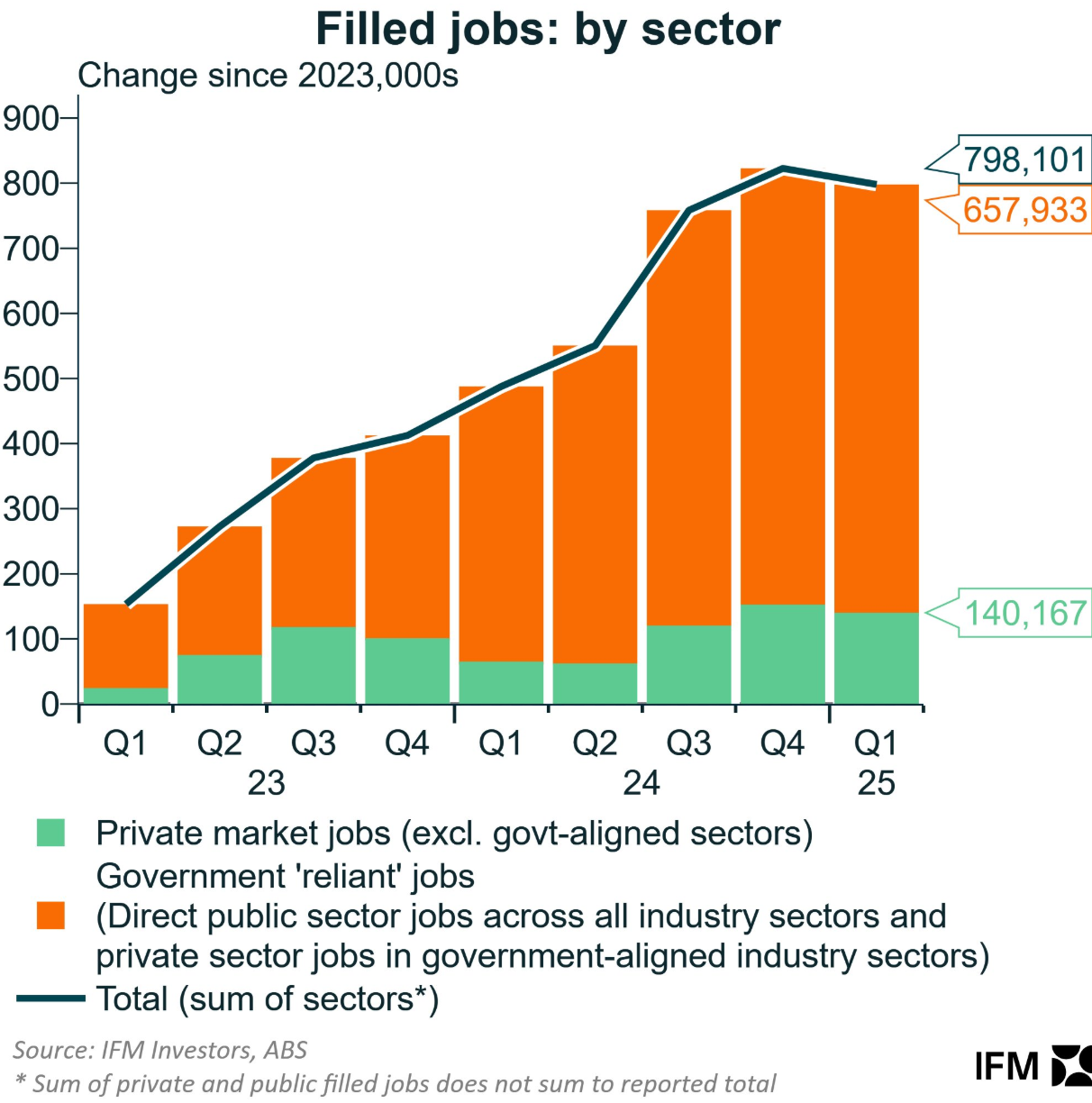

As the following chart from Alex Joiner at IFM Investors shows, roughly 80% of jobs created over the past two years have been in the non-market sector.

The non-market sector created nearly 658,000 jobs between Q1 2023 and Q1 2025, compared to only 140,200 jobs created in the market (private) sector.

The key risk facing Australia is that federal and state government austerity leads to job cuts in the non-market sector, at the same time as the market (private) sector retrenches.

Canada is currently experiencing such a retrenchment, as illustrated below by economists at the National Bank of Canada.

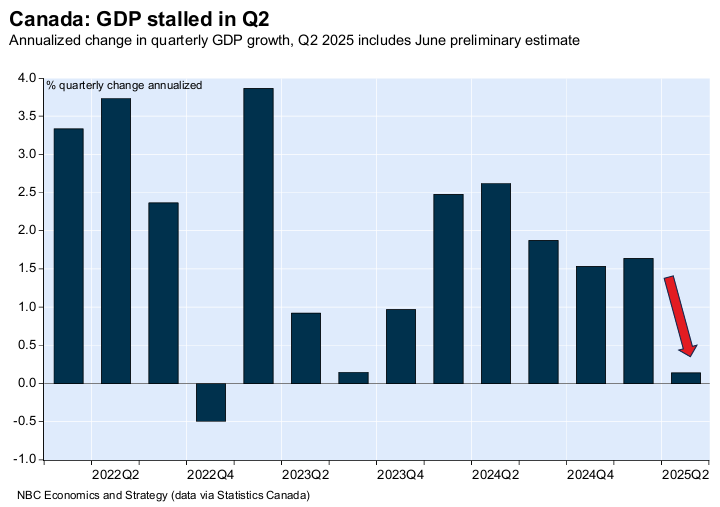

Statistics Canada estimates that GDP growth slowed to crawl in Q2 2025 at an annualised rate of only 0.1%.

“Overall, the data confirms that the Canadian economy is straining and the rising unemployment rate during the quarter corroborates this view”, the National Bank of Canada notes.

“Looking ahead, the outlook for the third quarter remains fragile, with recent surveys showing weak business sentiment toward investment and hiring”.

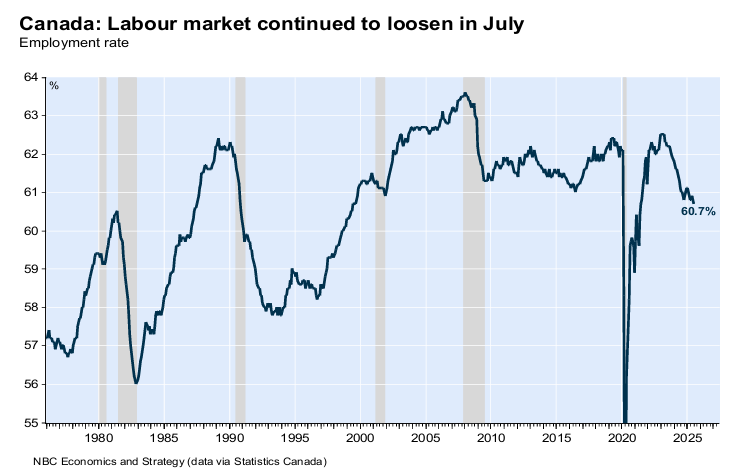

Indeed, Canadian employment fell by 40,800 in July, according to the Labour Force Survey, with full-time employment declining by 51,000.

The result was well below the median economists’ forecast of a 10,000 increase. Combined with a drop in the participation rate (from 65.4% to 65.2%), the unemployment rate remained unchanged at 6.9%.

However, the employment rate dropped to 60.7%, its lowest level since July 2021.

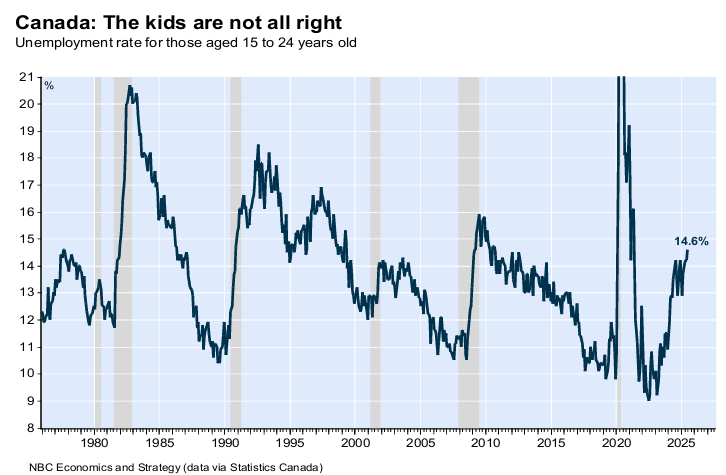

Canada’s youth bore the brunt, with 15- to 24-year-olds losing 34,000 jobs. The youth employment rate fell by 0.7% in July, hitting 53.6%—the lowest level since November 1998 (outside of the COVID-19 pandemic).

Meanwhile, the youth unemployment rate hit its highest level since September 2010 at 14.6%.

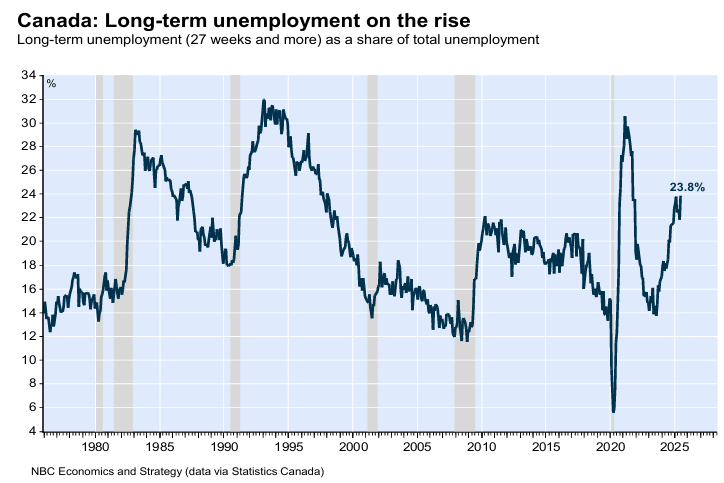

Long-term unemployment is also on the rise in Canada, with the share of workers unemployed for 27 weeks or longer at its highest level since 1998, excluding the pandemic.

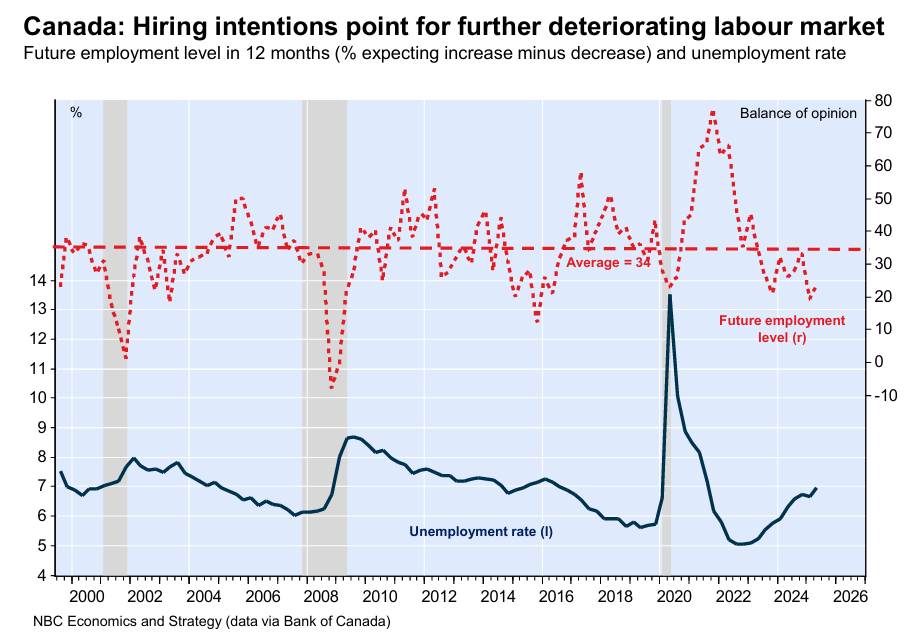

Firm hiring intentions have also collapsed in Canada, pointing to further job losses.

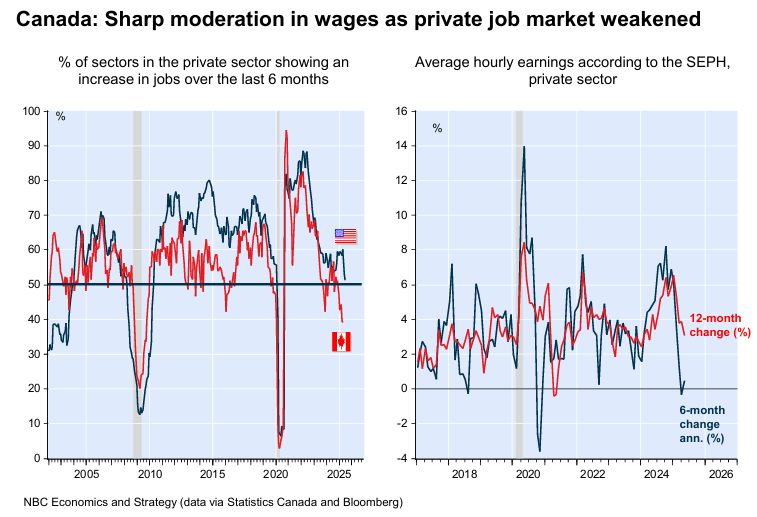

The deterioration of Canada’s labour market and the growing surplus of workers have slowed wage growth to a crawl, with an annualised rate of just 0.5% recorded over the last six months.

Canada provides a timely reminder that labour markets can deteriorate quickly.

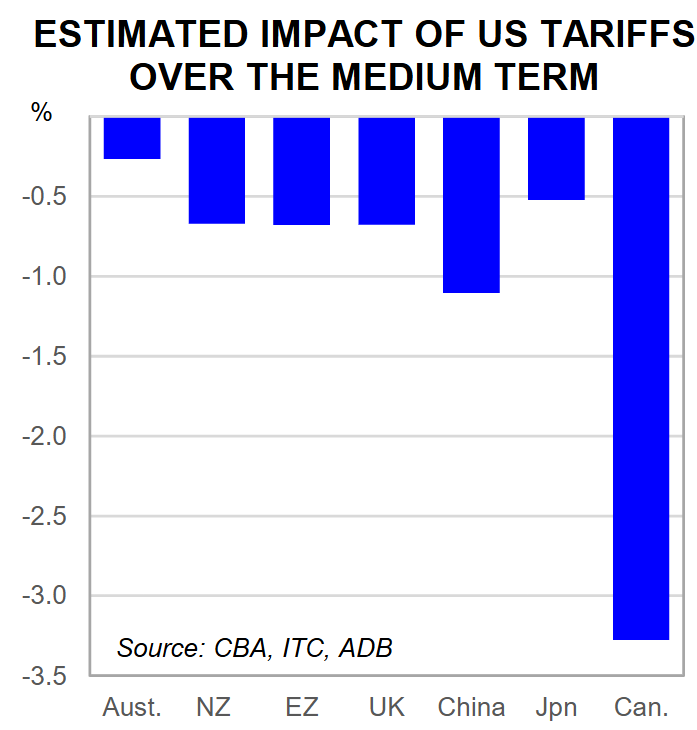

One major positive for Australia is that it is far less impacted than Canada by the Trump Administration’s tariffs.

As a result, our economy faces less downside than Canada’s.

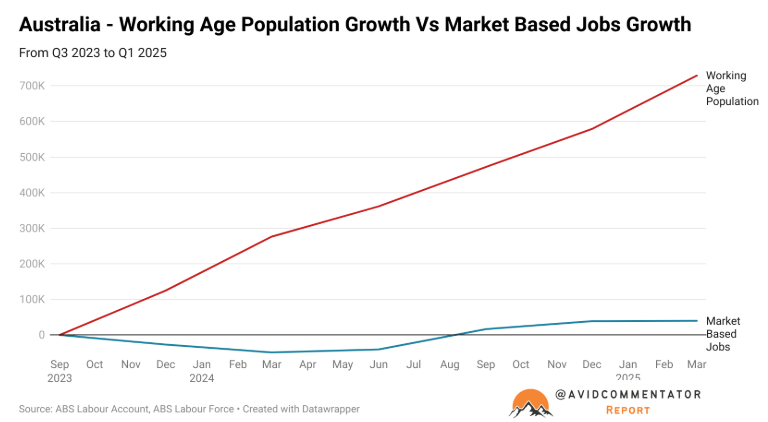

Nevertheless, we cannot rule out a significant increase in unemployment if the non-market sector contracts, the market (private) sector remains in its recessionary slumber, and the labour force continues to balloon on the back of high immigration.