Australia is a R&D wasteland

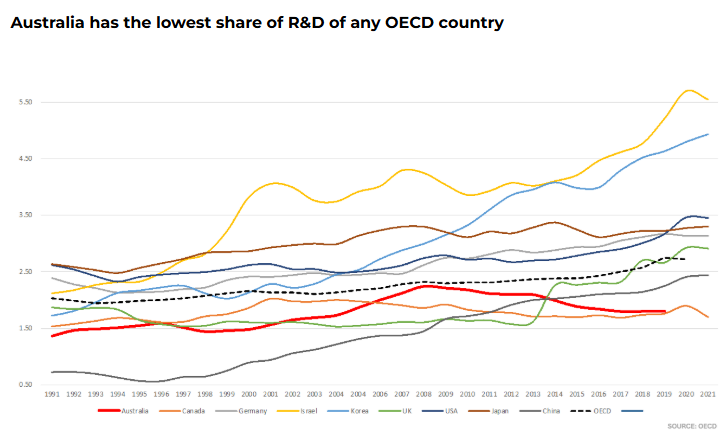

Australia’s annual R&D spending has also fallen to only 1.68% of GDP, well below the OECD average (3%) and the lowest among developed nations.

As a result, the Albanese government has launched a review into Australia’s R&D, which is analysed below by independent commentator and MB Subscriber, Stephen Saunders.

By Stephen Saunders

Thus far, Australia’s high-level, low-profile research and development (R&D) review puts the Treasury Line ahead of independent inquiry.

Running through 2024-25, this important review is typical of how Australia works. In other wealthy nations, it might have a higher profile, attracted political scrutiny, and sterner debate.

Not Down Under, where our top-20% of stakeholders ideate almost as one beehive. Despite its international purview, this review risks “talking among itself”.

Fortuitously kept afloat by humungous iron (Fe) and coal-gas hydrocarbon (CH) exports, the “lucky” (seat 11-A) country mistreats its own people to an immigration-led labour-growth economy—not business-led investment-growth.

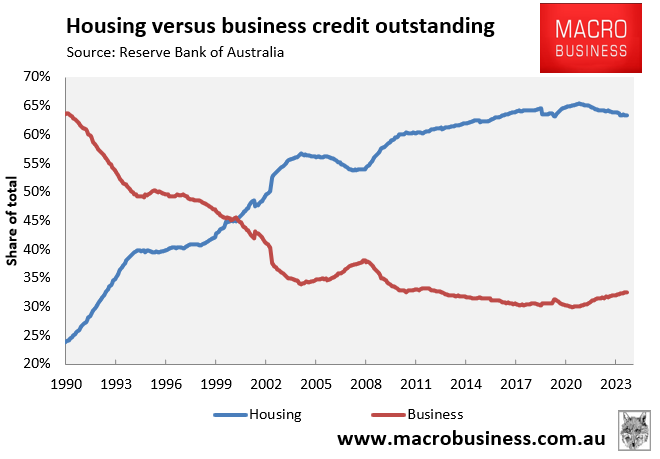

Bank-lending is siphoned off to the real-estate bubble, not business innovation.

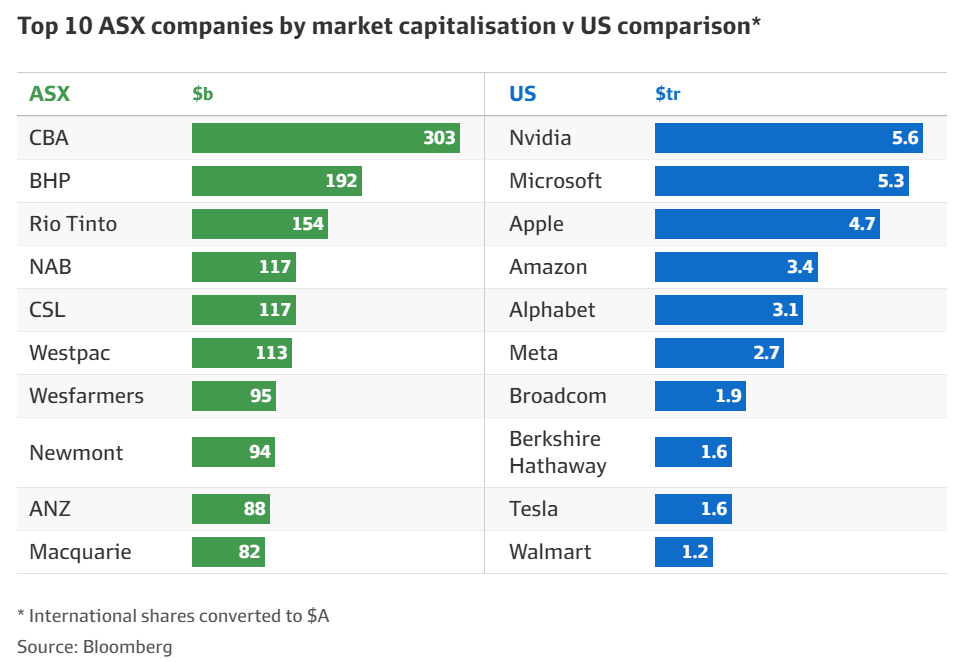

The top companies are dominated by banks and miners, not tech.

How do you kick-start R&D against that kind of indolence?

The review originated in 2024

The review materialised in the May 2024 Portfolio Budget Statements for Science, seeking to “maximise the impact” from our R&D. Academy of Science saw this as a generational opportunity for R&D to “maximise its contribution”. Financial Review said business “spends bugger all”.

Last December, terms-of-reference finally appeared. The review panel leader is former Australian accountant Robyn Denholm, who has risen meteorically to Chair of Tesla Inc. She was ticket 37 among 146 Treasury-anointed stakeholders at Labor’s gloriously consensual (but totally dishonest) jobs and skills summit.

Supporting Denholm are education-supremo Ian Chubb, rebounding from his carbon-credits fiasco, plus WA science-surgery icon Fiona Stanley, and startup-whiz Kate Cornick.

Science and Education Ministers immediately linked the review to Treasury’s Future Made in Australia (FMIA) concept, built on the UN’s fairy dust of a “net-zero transformation-stream”.

The quick-sticks discussion paper

Just two months later, the panel’s discussion paper emerged for two months’ consultation.

The Australian Industry Group’s submission thought commercialisation was central. Academy of Social Sciences thought social-sciences were central. Group of Eight universities wanted 3% of GDP for R&D, fully funded research grants, and more “skilled” migrants. All are talking their own books.

The paper’s Executive Summary makes a conventional claim—Australia is a research ace. In reality, there is too much inconsequential “research” chasing dodgy international rankings.

The panel admits that our economy lacks complexity and R&D has slid. No opportunities will be “ignored” they promise, hand on heart.

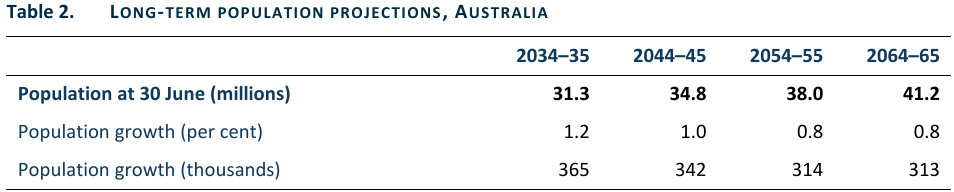

Their first chapter, Case for R&D, says R&D can build growth and productivity. Sure, but the absurd claim of Australia having “lower population growth” is just a Treasury Line.

Solely this century, Treasury has engineered a world-beating 46% acceleration to 27 million, 40 million-plus being their target. That might help explain the Figure 1 “backsliding productivity” shock or Figure 3 “economic simplicity” horror.

Source: Centre for Population (December 2024)

Under Treasury Rules, however, government reports don’t make those connections. Because it suits stakeholders.

Then, strong R&D is in the “national interest” to address “complex challenges”. Fair enough, but here comes a rerun of Treasury’s net-zero “transformation”.

What’s the State of Australia’s R&D system? We have strong foundational research, but we underinvest in R&D and do not adequately pursue “experimental development.”

Universities and industry are both on the same gravy train—Treasury’s quantitative-peopling not a business-led economy. Why would either team bust a boiler for experimental development?

Now to the Key issues, among our 40 universities, 60-plus medical or public research agencies, and other non-government research entities.

With “pressures on operating models”, university revenues and R&D are linked to enrolment “patterns in student markets”. Talk about being economical with the truth.

Denholm stays mum on Australia’s outsized overseas-student operations. These masquerade as our fourth largest “export” after the Fe and CH’s.

It’s no secret that casually-vetted cash-cow international students claim around half our massive net migration. This has given us the highest international student-intensity of any advanced nation.

Astonishingly, with one-third of 1% of the world’s population, we carry close to 15% of the international student trade. That’s a South Seas bubble for “vice” chancellors, not a sustainable industry.

With the artificial intelligence (AI) threat barely hitting second gear, this revenue-rich but financially struggling “export” model has already damaged university quality and ethics.

Australia likes directly preferring overseas students to locals, as sources of skilled workers or semi-skilled labour. Selfish Universities Australia applaud Albanese’s reverse-racist agreements, preferencing Indian qualifications and students over other nations.

Not only that, our National University (ANU) and other high-end campuses are themselves tireless propagandists for “export” education. Downsizing and quality reform of this student boondoggle might make better sense, research wise, but Denholm’s looking the other way.

Business-led research, her paper continues, is a Good Thing, building “diversification, resilience, and growth”. Relative to OECD norms, however, business-based research has plummeted since 2009. This is largely attributable to “mining sector” trends.

Would you believe “stronger manufacturing” would help? I do. Would you believe FMIA can instigate that? I don’t. Not when superimposed on our self-sown manufacturing landmines – steep prices for land, labour, energy, transport, and communications.

What would have been relevant here is the potential China/US development of intelligent or smart manufacturing. Robotics and energy-heavy, but beyond Australia’s ken.

The next point is our “vibrant” startup scene. Financial Review loves this stuff, seeing evidence our regressive economy is on track. Who doesn’t know somebody who knows someone working at Atlassian or Canva?

Also plausible is that Australia “increasingly” relies on small and medium enterprises to lift business R&D, though their numbers have “contracted” since 2008.

Could this train-of-thought be leading somewhere? Not when Treasury Line smothers discussion:

“Growing medium enterprises includes de-risking market adoption. Removing barriers to business dynamism and competitive pressures, encouraging firms to approach the innovation frontier, will lead to improved labour productivity.”

Back then, to the slide in large-enterprise R&D. Again, why would these commonly rent-seeking companies plunge big time into R&D? Cupidity and oligopoly are reward enough.

The Commonwealth’s R&D effort is spread “broadly and thinly”. Over 2024-25, there’s $14.4 billion (less than the largesse for fee-charging religious schools) across “14 portfolios and 151 programs”. The biggest slice is the R&D tax incentive for businesses.

Though Australia’s said to have “led the world” in developing high-quality, connected, and available R&D infrastructure, we’re also a “patchwork” with gaps. Funding for institutional versus “national-priority” versus “landmark-global” R&D infrastructure comes from multiple sources, with limited coordination.

Commonwealth R&D sits well below the OECD standard of 2.73% of GDP. Also, we’re low on the global index of venture capital, proportional to GDP. Hence, casual suggestions of redeploying our huge super-funds or drawing down on local “philanthropy”.

Collaboration across sectors is weak. Academics don’t percolate much into industry, or vice versa. Also, our workforce is deemed “not aligned” to the needs of the economy, particularly STEM (science, technology, engineering, and maths) skills.

Panel, how come that’s still true?

Since 2005, we’ve had a big increase in university participation, with technical training going backwards and the government insisting 55% of young Australians should have degrees by 2050. We’ve also had massive increases in immigration, purportedly to fix “skill shortages”.

Before 2007, Australia had never experienced 200,000 annual net migration. Yet 2022-25 will top 1.3 million, 70% higher than the previous one-term record. Pro-government influencers at ANU “Migration Hub” contort this into a “shortfall”. Suits stakeholders.

Panel should be wondering exactly how many years of unending local graduates and unlimited “skilled” migrants it would take before our workforce would finally “align” with R&D?

Noting the likely effects of AI on R&D, the discussion paper usefully concludes with six international R&D reforms—US, Germany, South Korea, France, Israel, and UK.

Maybe one or the other will get a guernsey in the final report. Perhaps Israel, also a “pioneering” desert nation whose population resembles ours in size. They’re a tad more energetic, perhaps. No “netting” of Woodside or Santos gas to “zero” for them.

The review is compromised

Every year, the government produces Budget Paper 3 and Population Statement. Where Treasury repeats their time-honored fib for stakeholders. Massive immigration isn’t engineered—it just “happens”.

Indeed, the Treasurer and pro-government influencers insinuate Australia “isn’t allowed” to manage immigration. That’s more for UN/OECD/EU/IMF club, also our “free” trade agreements.

In disrespectful terms, the treasurer’s ivory-tower economic directions play out somewhat like this: third-world resource-giveaways, low-wage population replacement, government and care jobs aplenty, egotistical productivity and net-zero fallacies, overrated export-education, and incentivised real-estate speculation.

Reprising jobs summit, he’s treating (consensual) stakeholders to a productivity roundtable to duck productivity questions.

By and large, this R&D review seems obliged (or chooses) to take our South Seas economic model at face value. Denholm are her panel looks compromised. They’ll struggle to generate the incisive thrusts our R&D effort would really need.

Having said that, perhaps they could try for targeted increases in R&D spending, cleverer approaches to R&D infrastructure, better public-to-private linkages, fillips for the venture-capital scene, or whatever. Might help at the margin.

Could this invisible investigation surprise with a few Tesla-style zingers? Let’s see. After all, ex-DOGE multi-dad Elon Musk and his company are valued at roughly three-quarters of our entire economy.