Last year, the Albanese government vowed to streamline the list of occupations eligible for employer-sponsored visas.

The first draft of the new job list, devised by the government agency Jobs and Skills Australia (JSA), reportedly omits chefs, cooks, bakers, and managers, which has angered the hospitality industry.

The hospitality industry is now gearing up for a fight, with the head of the Australian Hotels Association, Stephen Ferguson, arguing that migration is vital to the business model of many restaurants and cafes:

“We were surprised to see chefs and cooks marked as uncertain”, he said.

“It’s a very hot topic for our members … The fact is we have a shortage. There’s got to be a recognition of that need”.

“At the moment, there are 8,000 chef positions being advertised on [job website] Seek … I can guarantee you that productivity will decline if you don’t have enough workers to generate as much turnover as you can”.

“If we can’t open because we don’t have a chef, it means the barman doesn’t have a job, the manager, the receptionist, and the business isn’t as productive as it could be”.

“Unfortunately, many back-of-house roles in the hospitality industry just aren’t popular amongst school leavers”, Ferguson said.

The hospitality industry is experiencing labour shortages primarily because it offers poor wages and working conditions.

Hospitality offers the lowest rates of pay in Australia by a wide margin and is ground zero for wage theft, especially from migrant workers.

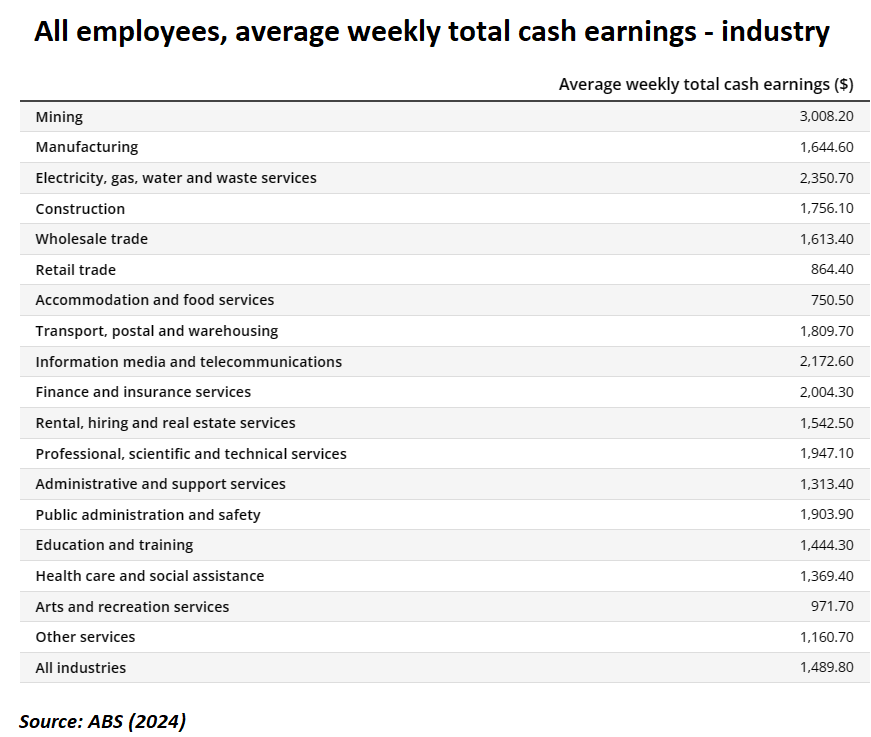

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), in May 2023, employees in the accommodation and food services industry earned an average of only $750 a week, nearly half the economy’s average of $1,490.

The hospitality industry only has itself to blame for labour shortages.

Many people would work for the sector if it provided adequate remuneration/superannuation, stable, part-time or full-time opportunities, and career paths/apprenticeships for those who desired them.

However, workforce shortages will persist as long as hospitality pays low wages and provides poor working conditions.

Any industry that relies on cheap, exploited migrant labour is unsustainable and requires significant structural reforms.

Giving the hospitality industry easier access to foreign labour will exacerbate the current systemic exploitation, keeping wages low and depriving local workers of stable employment prospects and a decent wage.

Politicians must stop pandering to special interests, such as the Australian Hotels Association. Otherwise, real wage growth in Australia will remain stagnant, and exploitation will continue to be prevalent.

I prefer to eliminate the skilled occupations list altogether and simply lift the wage floor for all migrant workers to a level above the median full-time wage (currently about $90,000).

Doing so would restrict work visas to higher-skilled professions, reduce population pressures, lift productivity, and increase average income tax receipts.

If Australia wants a skilled migration system, it must ensure that the migrant wage floor reflects a skilled wage.

Otherwise, Australia’s immigration system will remain largely unskilled.