The latest Statement of Monetary Policy (SoMP) from the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) explicitly noted that Australia’s record immigration-fueled population growth is driving home prices and rents higher.

The RBA also warned that the situation will continue as demand via population growth continues to outrun new housing supply.

Below are key extracts from the SoMP relating to this issue.

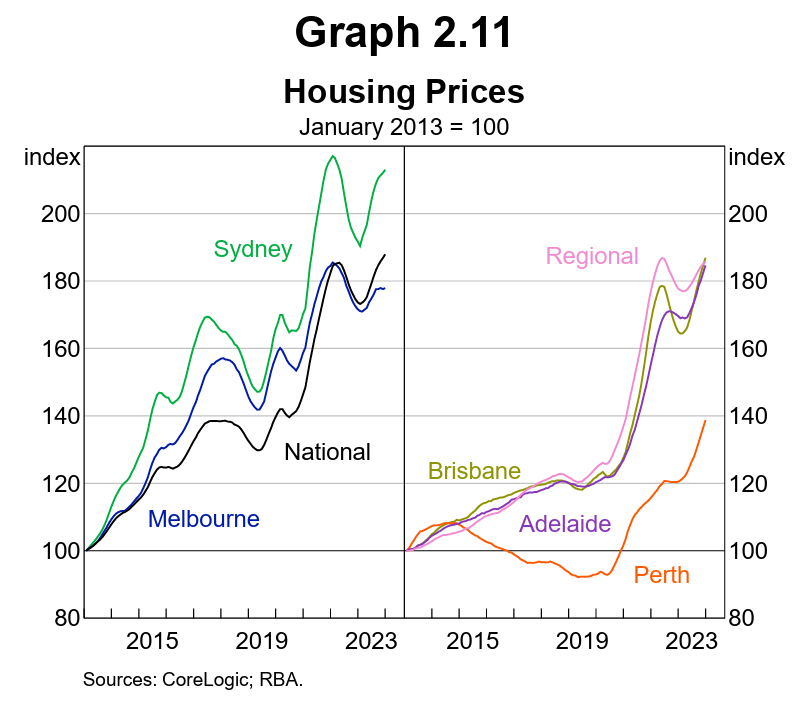

National housing prices increased strongly over 2023 to be above their April 2022 peak (Graph 2.11).

Prices have increased across most capital cities and regional areas, supporting household wealth, although price growth has slowed more recently in Sydney and Melbourne.

The rebound in housing prices reflected a combination of stronger demand for established housing (partly due to strong population growth) and a limited supply of dwellings…

The rental market remains tight and the ongoing weakness in dwelling investment suggests this is unlikely to ease in the near term.

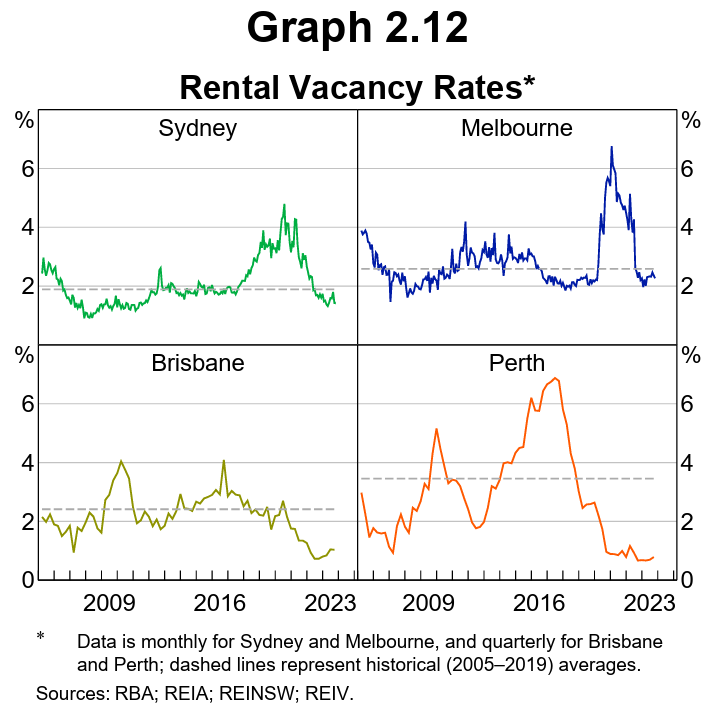

Rental vacancy rates remain low in most areas (Graph 2.12).

This is consistent with a limited supply of new dwellings, strong population growth and a shift in preferences during the pandemic towards more residential space that has led to a lower average household size. Although average household size has increased in capital cities over the past year, it remains well below pre-pandemic levels…

The supply of new dwellings has remained constrained, with dwelling investment below pre-pandemic levels.

Quarterly commencements are at their lowest level in over a decade and capacity constraints have continued to limit the pace at which builders can work through the existing pipeline of residential construction, with labour shortages acute in the latter stages of construction…

Uncertainty around higher interest rates, elevated construction costs and longer building times have weighed on buyer sentiment…

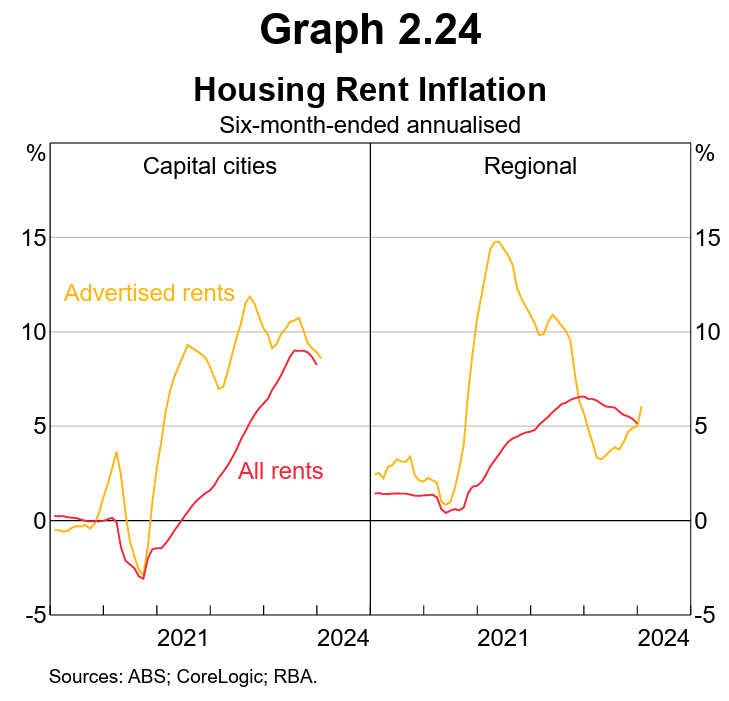

Rent inflation remains high, and this is expected to persist because of the ongoing tightness in rental market conditions.

Rent inflation for the stock of rents captured in the CPI (which excludes regional areas) was 0.9% in the quarter and 7.3% the year (Graph 2.24). This would have been 1½ percentage points higher over the year if not for the increase to Commonwealth Rent Assistance that came into effect in September 2023.

Tight rental market conditions across the capital cities are expected to contribute to continued high rent inflation, as recent increases in monthly advertised rental growth flow through to CPI rents…

Why does the RBA support mass immigration when it is unequivocally behind the nation’s housing shortage and is the primary driver of Australia’s rental inflation?

Australia will never build enough homes or infrastructure so long as its population continues to grow at a feverish pace through high immigration.

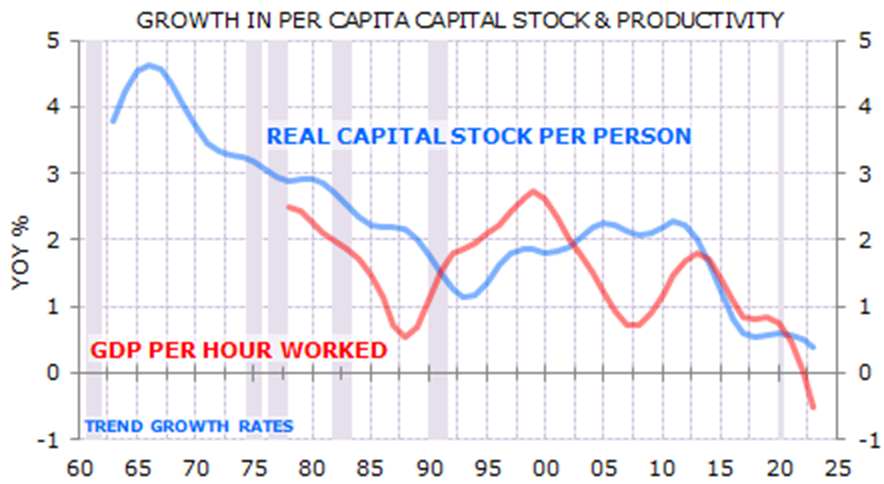

In turn, Australia’s productivity will continue to suffer as the population grows faster than business investment, infrastructure, and housing, resulting in “capital shallowing”:

Source: Gerard Minack

As explained in independent economist Gerard Minack’s November report:

“Australia’s economic performance in the decade before the pandemic was, on many measures, the worst in 60 years”.

“Per capita GDP growth was low, productivity growth tepid, real wages were stagnant, and housing increasingly unaffordable. There were many reasons for the mess, but the most important was a giant capital-to-labour switch: Australia relied on increasing labour supply, rather than increasing investment, to drive growth”.

“Australia’s population-led growth model was a demonstrable failure in the 15 years prior to the pandemic. Remarkably, the country now seems to be doubling down on the same strategy. The result, unsurprisingly, is likely to be more of the same”.

Large-scale immigration also diverts resources, encouraging the establishment of low-productivity “people-servicing” firms while redirecting the nation’s productive effort into infrastructure and housing.

Australia is also unique in that it pays its way in the world mostly through the sale of its fixed mineral reserves.

Importing huge volumes of migrants dilutes the mineral wealth across more people, resulting in less wealth per person (other things equal).

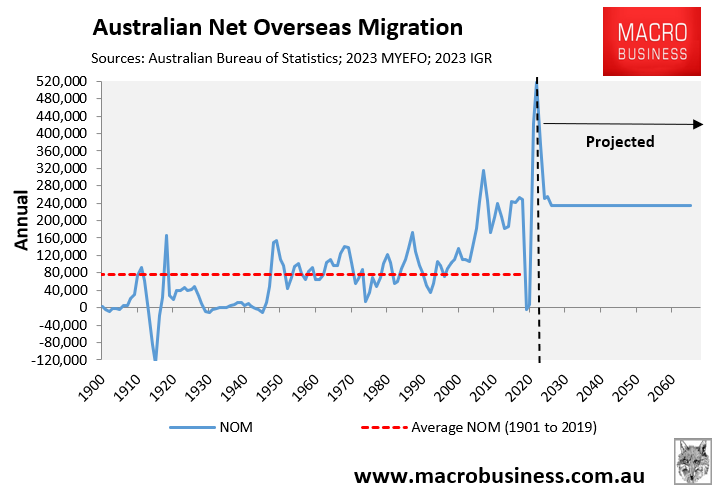

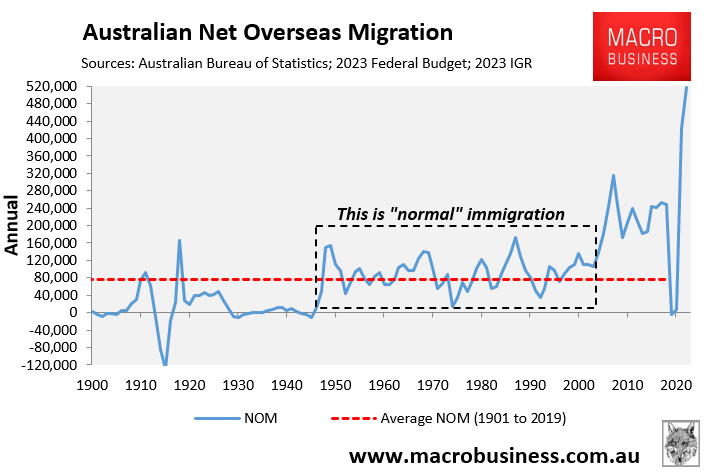

The RBA should be honest with itself and the Australian people and demand lower, sustainable levels of immigration in line with pre-2005 norms:

This “normal” level of immigration worked well for Australia and was at a level where business investment, infrastructure, and housing broadly kept pace with population demand.