Australia has the world’s highest share of international students as a proportion of its population because it offers the most generous post-study work rights (PSWR) in the world.

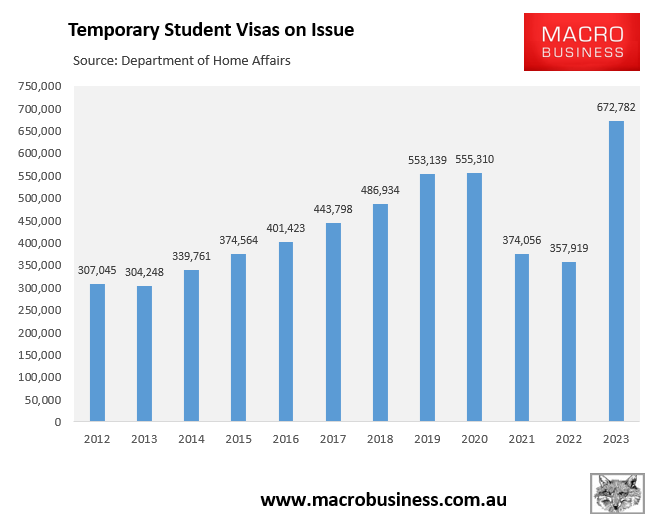

As of October 2023, there were nearly 673,000 student visas on issue in Australia – easily the highest number on record:

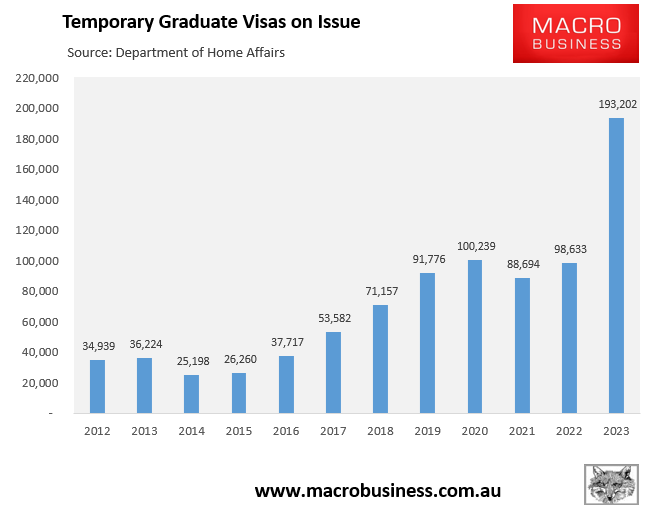

There were also a record 193,000 temporary graduate visas on issue:

Combined, this means that an extraordinary one in 30 people in Australia in October were on either one of these visas – a world record share of a nation’s population.

The “new migration strategy” released earlier this month by the Albanese government will limit PSWR for international students to two or three years, down from four, five, and six years in July.

However, Australia’s second largest and fastest growing major cohort – Indian students – will be exempt from the new rules.

Canada is similarly limiting graduate PSWR to three years, with 18-month extensions available since 2021 scheduled to expire.

This brings both countries’ PSWR systems in line with those in the United States and New Zealand, which also allow for up to three years.

Meanwhile, the United Kingdom is reconsidering the automatic two-year PSWR work visa that it reinstated only 30 months ago.

Ly Tran, a Deakin University international education researcher, claims “prejudice” against international students and graduates is on the rise in Australia.

Tran claims the shortening of PSWR won’t help international graduates acquire the job experience they needed nor help ease the skills shortages present in higher-skilled professions.

Tran has also attacked the migration strategy’s recommendation to reduce the maximum eligible age for a temporary graduate visa (TGV) from 50 to 35, claiming that skilled individuals will be forced to study, live and work elsewhere.

“Reducing the maximum age cap to 35 also unfairly impacts graduates with carer responsibilities, such as mature-age mothers who delay returning to university for postgraduate studies”, she says.

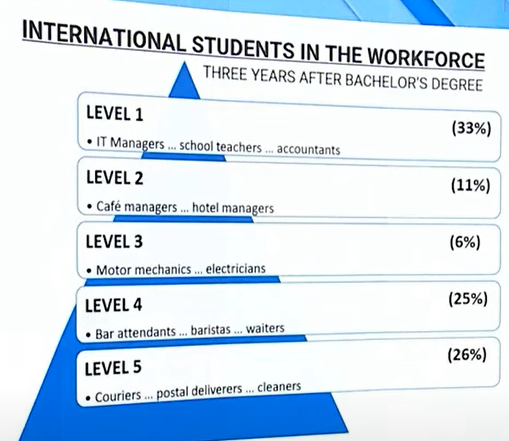

The notion that international student graduates are filling vital skills shortages in the economy and adding greatly to Australia’s skills base in demonstrably false.

The below graphic from Sky News’ Tom Connell shows that 51% of international student graduates with a bachelor’s degree still in Australia after three years are working in low-skilled Level 4 or Level 5 jobs:

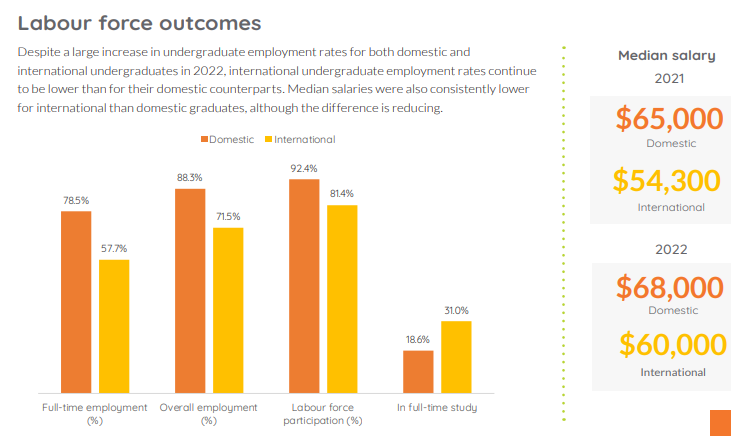

These findings are corroborated by the most recent Graduate Outcomes Survey (GOS), which shows that international graduates have far lower employment rates, participation rates, and median earnings than domestic graduates:

Source: Graduate Outcomes Survey (2022)

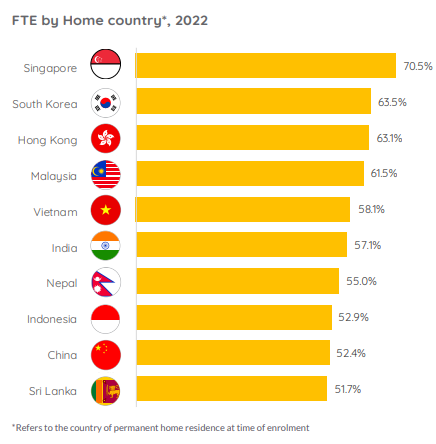

Worryingly, each of Australia’s three major source countries for overseas students – China, India, and Nepal – has dismal labour market outcomes in terms of full-time employment:

Source: Graduate Outcomes Survey (2022)

It is no surprise that Australia is suffering widespread skills shortages if this is what the tertiary education industry is producing in record numbers.

Australia’s international education Ponzi scheme has literally helped create a massive underclass of low-paid, low-skilled migrant workers.

It is likely to continue because the Albanese government signed two migration accords with India this year, which include provisions such as:

- Indians will be granted five-year student visas with no limit on the number who can study in Australia.

- Indian graduates of Australian higher institutions on a student visa can apply to work for up to eight years without visa sponsorship.

- Australia will recognise Indian vocational and university graduates as “holding the comparable AQF qualification” for entrance to higher education and general employment.

These migration agreements will make Australia an even more appealing destination for lower-skilled Indians seeking work and residency in Australia.

Instead of lowering standards to entice large volumes of sub-par students to Australia, policymakers should instead focus on attracting a small pool of excellent (genuine) students by significantly raising financial barriers to entry as well as entrance requirements (particularly for English language proficiency), and removing the clear link between studying, working, and permanent residency.

International education should be all about quality over quantity, and excellence over volume.

Otherwise, Australia will repeat the same mistakes of the past decade with youth unemployment, wage theft, exploitation and crush-loaded housing and infrastructure becoming endemic, alongside a growing migrant underclass.