Jobs and Skills Australia has released its annual skills priority list, stating that the number of occupations with workers in short supply rose from 286 last year to 332.

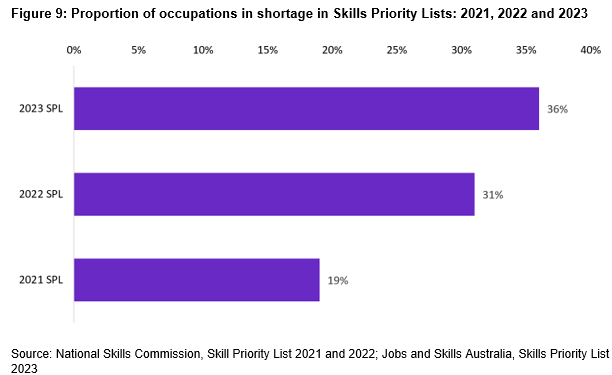

With occupations such as tax accountants and pilots added to the list, it means that 36% of occupations were supposedly experiencing worker shortages in the past year, up from 31% in 2022 and 19% in 2021.

Almost half of all professional occupations were in shortage according to the report.

However, despite the claims of widespread skills shortages, only 1% of surveyed employers reported increasing advertised salaries after failing to fill a job vacancy, Jobs and Skills Australia said:

“Wage growth to address shortages has not responded as expected”

“For all skills shortages, conventional economics suggest that increasing wages is one lever that employers can pull to attract more workers”.

“Jobs and Skills Australia’s Survey of Employers who have Recently Advertised (SERA) found that over the 3 years from 2021 to 2023, few employers changed remuneration in response to skill shortages”.

“In the 2023 SPL period, around 1% of employers adjusted remuneration to attract skilled workers to fill vacancies”.

No wonder schools, hospitals and aged care homes are always short of staff. Instead of lifting advertised salaries to attract staff, employers just re-run the ad and then complain of shortages.

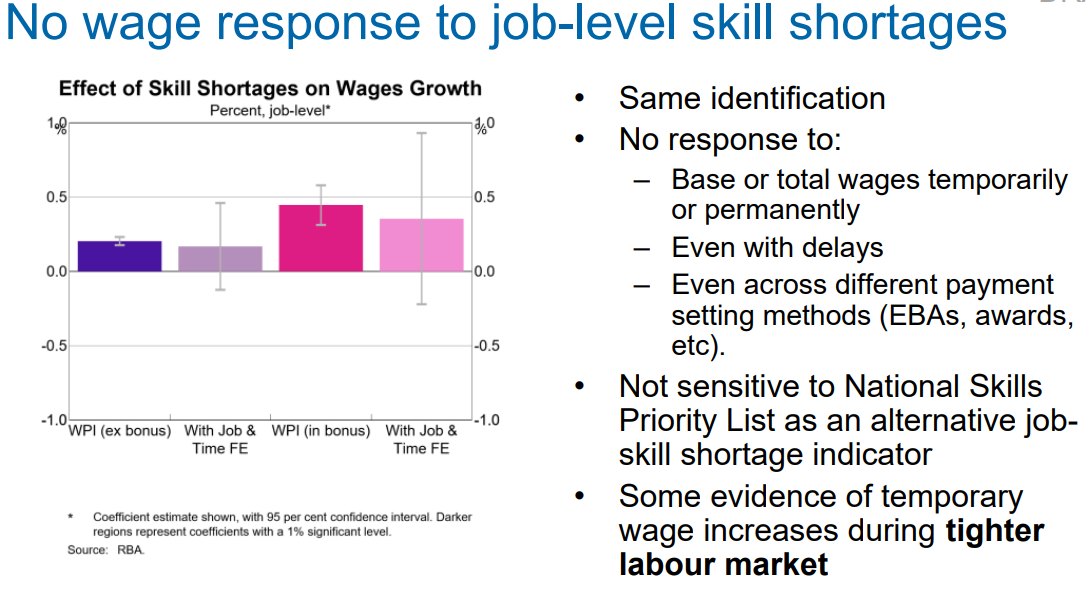

These results mirror similar from the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), which were published on MB last week.

In particular, the RBA showed no wage response to job-level skill shortages:

The RBA’s Key findings also suggested the claim of widespread skills shortages doesn’t stack up:

Meanwhile, Robert Half director Andrew Brushfield told The AFR that despite the record net overseas migration over the past year, the recruitment agency had not observed a significant increase in the number of skilled migrants applying for jobs.

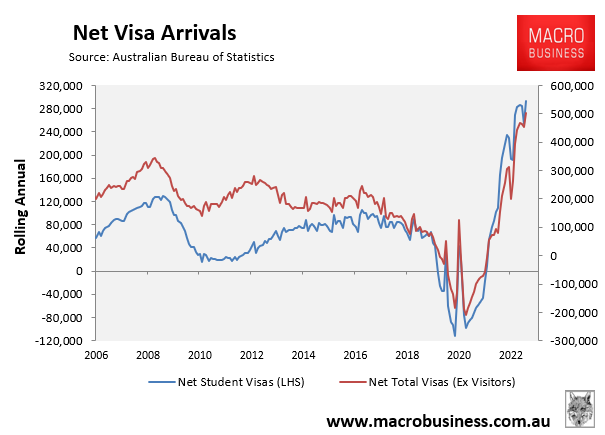

This likely relates to the fact that most of Australia’s net overseas migration has been unskilled, including through the student visa channel:

The never-ending claim of skills shortages quite frankly not supported by evidence.

Australia has never had more people completing university degrees and never had more immigration.

Australia’s population has ballooned by 7.5 million people this century via mass immigration, most of which is supposedly ‘skilled’.

Yet, claims of skills shortages have persisted for 20 years, with the ‘problem’ getting worse.

In a 2002 Senate Inquiry Australia’s business lobby complained of ‘serious skill shortages and skill gaps’ in Australia and warned that unless we import a lot of workers, the economy would suffer and the nation would go backwards:

“According to the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI), the lack of suitably qualified staff has been a major concern for Australian industry over the past decade, and is one of the most significant barriers to investment”

“The Australian Industry Group (AiG) … reports that several industry sectors, including manufacturing, are continuing to experience serious skill shortages which, unless effectively addressed, may have severe and lasting consequences for Australian enterprises”.

“The Business Council of Australia submission points to the risk of future broad-based skill shortages resulting from an ageing population”.

You could change the date of the above statements from 2002 to 2023, given nothing has changed. The same big business lobbyists continue to run the same talking points on the need for more immigration.

When firms in Australia have easy access to cheaper migrant workers, they have little motivation to automate, capital per worker falls, and the nation’s productivity and wage growth fall.

This is precisely the predicament that Australia found itself in the decade preceding the pandemic, suffering from both low wage growth and low productivity growth as immigration boomed. It was a recipe for declining living standards.

Instead, in order to optimise Australians’ well-being, we requires a skilled migration system that prioritises quality above quantity.

A real skilled visa system would raise workers’ incomes and purchasing power while also raising productivity by incentivising employers to invest in productivity gains.

The first best solution is to set a pay floor higher than the median full-time wage ($85,000 currently) and index it to wage growth for all migrants on work visas (excluding working holiday makers).

Simply implementing this fundamental reform would maximise the economic benefits of skilled migration.

Local workers would no longer be underpaid. The complexity of the visa system would be minimised. Raising the income threshold (quality bar) would reduce overall immigration to Australia, both directly (fewer workers arriving) and indirectly (making it more difficult for other temporary migrants, such as foreign students, to convert to a permanent skilled visa).

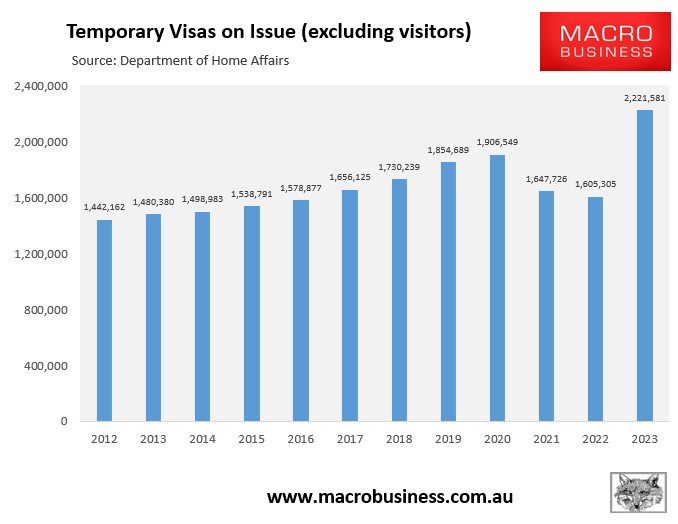

Unfortunately, the Albanese government has taken the opposite strategy, opening the floodgates to low-skilled immigration:

We all know what will happen.