One of the great economic paradoxes afflicting Australia is that the nation has never had more people completing university degrees and never had more immigration, yet ‘skills shortages’ are worse than ever and productivity stinks.

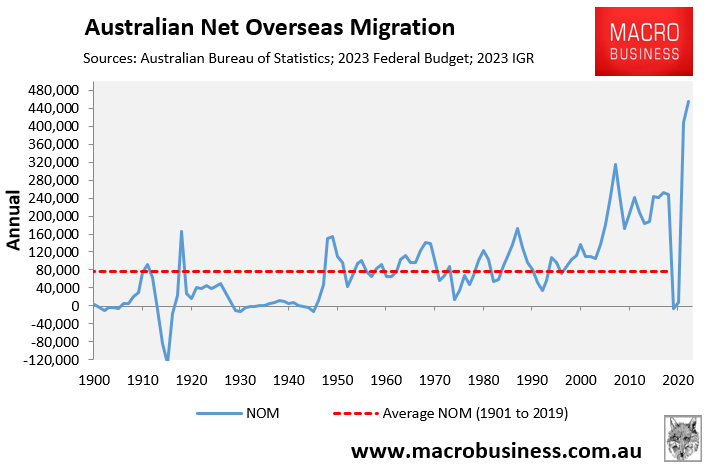

Think about it for a moment. Australia’s population has expanded by 7.4 million people this century, primarily via mass immigration (most of it purportedly skilled):

Domestic university enrolments also soared 43% between 2008 and 2020:

Yet, Australia’s skills shortages are supposedly worse than ever. How does that work?

We have also been fed the same skills shortage lie for over 20 years.

For example, a Senate Inquiry from 2002, put forward by the Howard Government on behalf of the business lobby, complained of ‘serious skill shortages and skill gaps’ in Australia and warned that unless we did something about it – i.e. import a lot of workers – Australia’s economy would not develop and would simply end up going backwards. Below are key extracts from this 2002 inquiry:

‘According to the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI), the lack of suitably qualified staff has been a major concern for Australian industry over the past decade, and is one of the most significant barriers to investment…

‘The Australian Industry Group (AiG) … reports that several industry sectors, including manufacturing, are continuing to experience serious skill shortages which, unless effectively addressed, may have severe and lasting consequences for Australian enterprises…

‘The Business Council of Australia submission points to the risk of future broad-based skill shortages resulting from an ageing population’…

You could literally change the date from 2002 to 2023, given nothing has changed. The same lobbyists continue to run the same tired talking points on the need for more immigration.

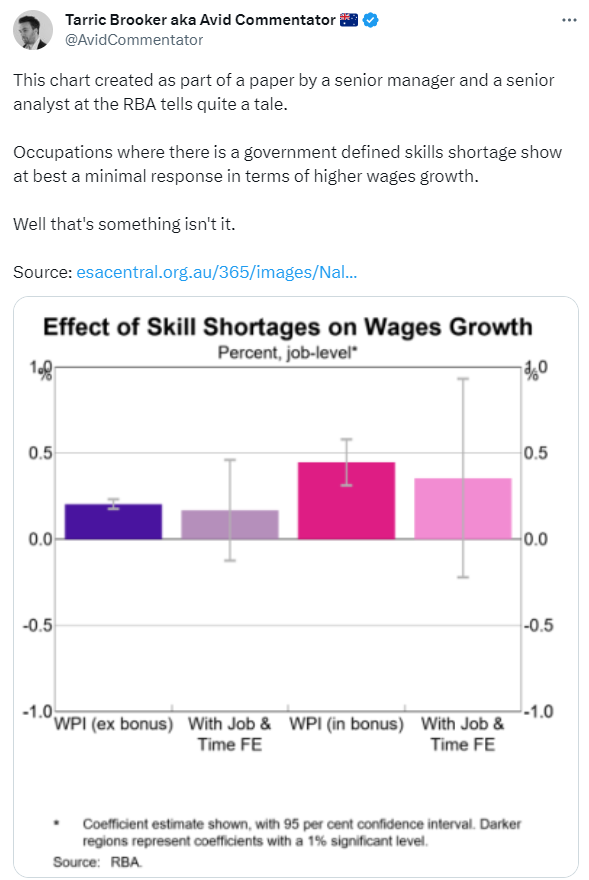

Hilariously, independent economist Tarric Brooker posted the below chart on Twitter showing how wage growth for occupations where there is a government defined skills shortage is only slightly higher than average:

The full RBA presentation is available here. Check out the slides below.

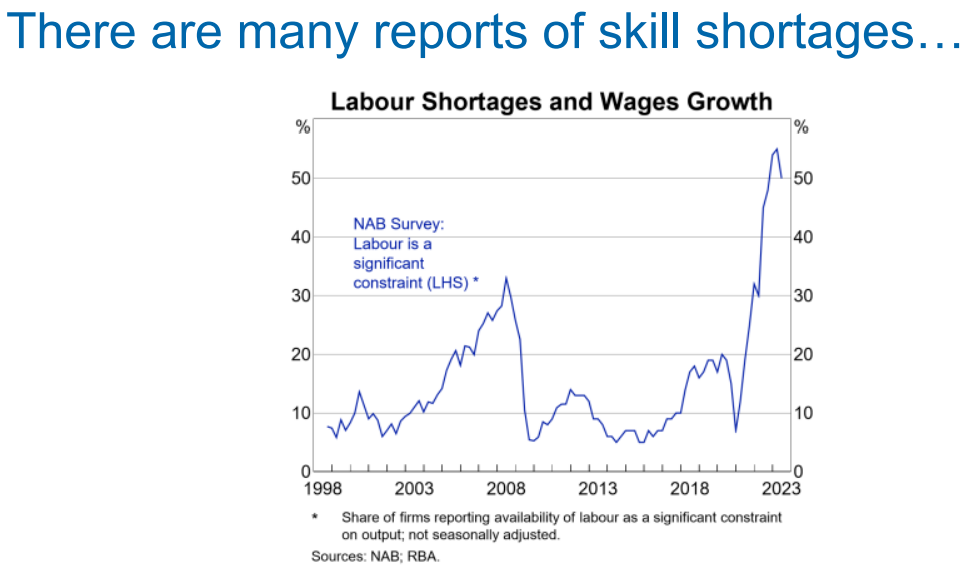

There are many reports of skills shortages:

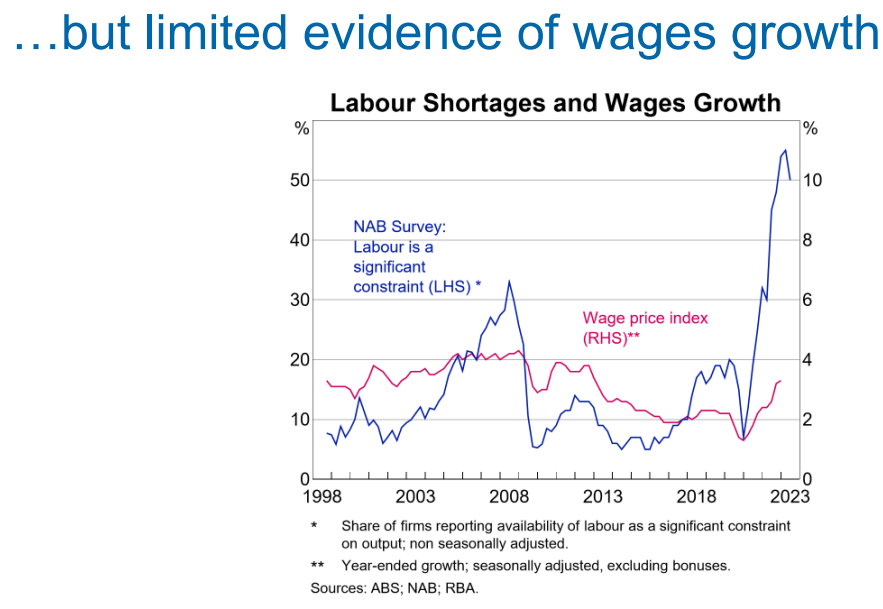

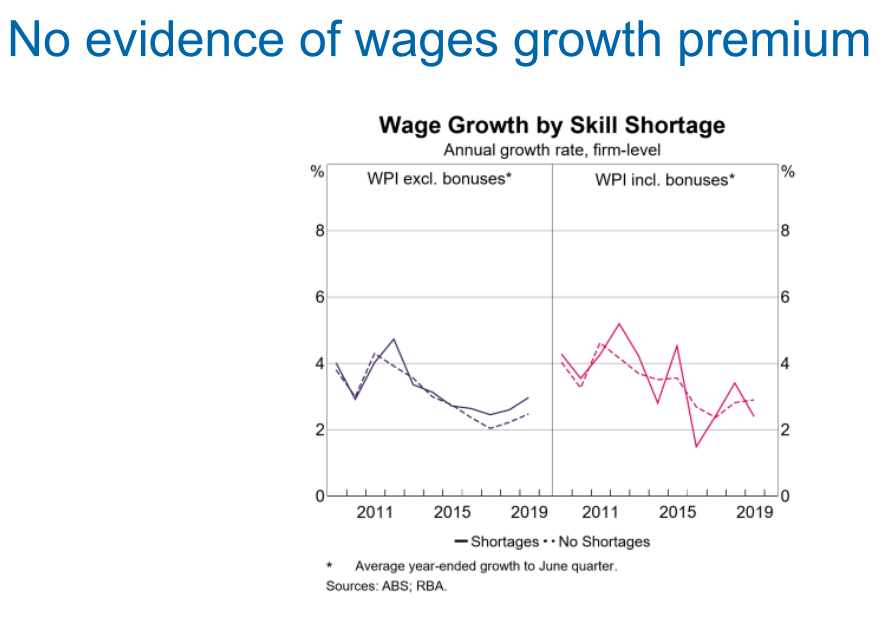

But limited evidence of wage growth:

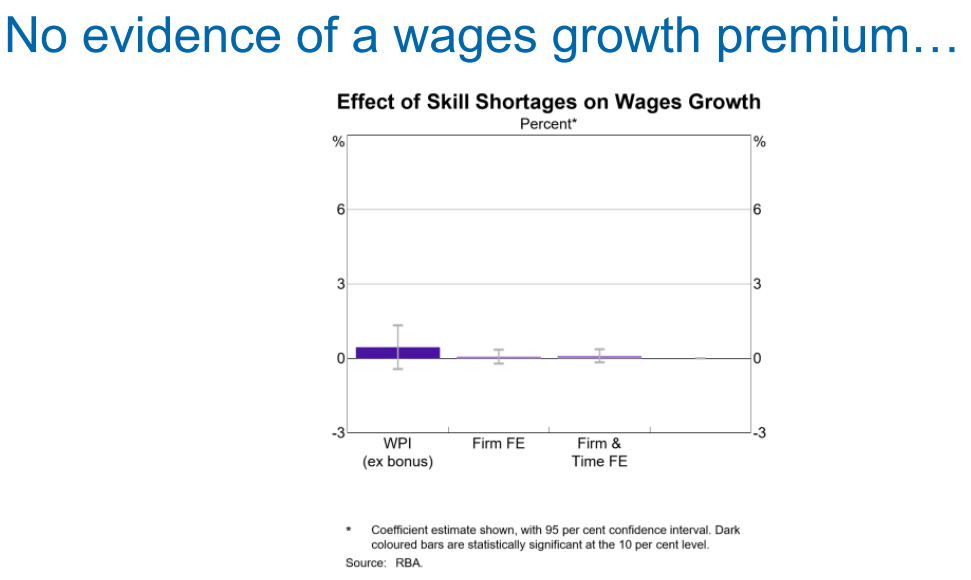

And no evidence of a wage growth premium for jobs with skills shortages:

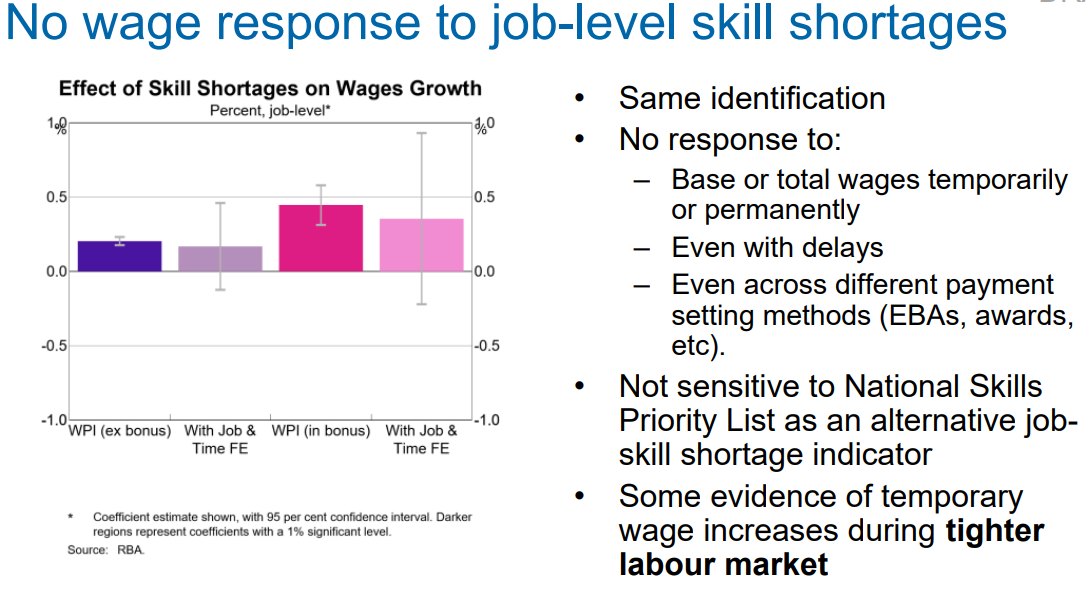

There is also no wage response to job-level skill shortages:

Key findings show skills shortage claims don’t stack up:

When Australian employers are given easy access to cheaper migrant workers they have little incentive to automate, capital per worker shallows, and the nation’s productivity and wage growth falls.

This is the exact situation Australia found itself in the decade preceding the pandemic, suffering from both poor wage growth and low productivity growth as immigration boomed. It was a prescription for falling living standards.

Instead, Australia needs a skilled migration system that prioritises quality over quantity in order to maximise the wellbeing of Australians.

A genuinely skilled visa system would increase workers’ wages and purchasing power while also increasing productivity by rewarding businesses for investing in productivity gains.

The logical approach is to set a pay floor above the median full-time wage ($85,000 currently) and indexing it to wage growth for all migrants on work visas (other than working holiday makers).

Simply implementing this basic reform would maximise the economic benefits of skilled migration.

Local employees would no longer be undercut. The visa system’s complexity would be reduced. Lifting the income requirement (quality bar) would also lower overall immigration into Australia, both directly (fewer workers arriving) and indirectly (making it more difficult for other temporary migrants, such as foreign students, to convert to a permanent skilled visa).

Sadly, the Albanese Government has chosen the opposite approach by opening the floodgates to low-paid, lower-skilled migrants.

We all know how that will turn out.