If you thought China was about to recover on a cyclical turn, here is Societe General on inventories to hose that idea.

Inventory reduction was a key but less noticeable factor behind industrial sector weakness in 2Q23. Based on various indicators, we are inclined to think that the worst of the destocking is over, pointing to a smaller drag on industrial activity in 2H23.

But given that the inventory-to-sales ratio is still high in mid/downstream sectors and that weak domestic and export demand is likely to persist, we do not foresee restocking at least until next year.

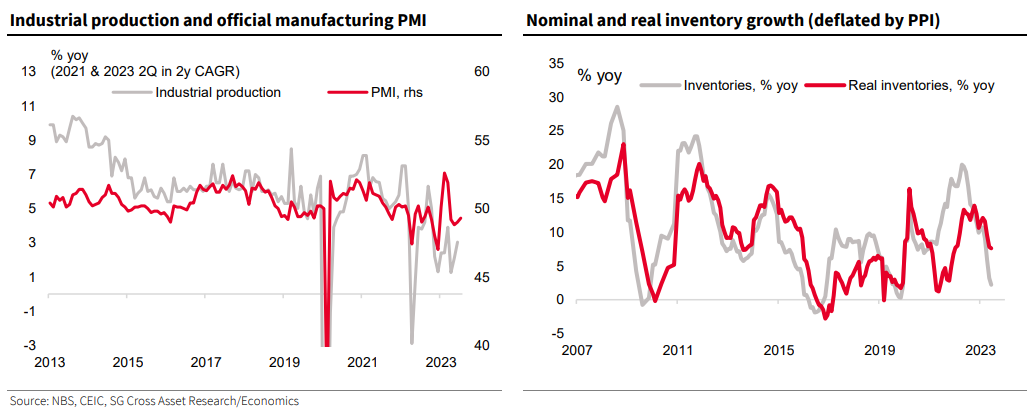

China’s industrial sector has experienced pronounced weakness this year. The manufacturing PMI has been below 50 again since April after a short-lived recovery in 1Q23 following the lifting of the lockdowns.

Based on seasonally adjusted data provided by the NBS, the sector expanded by 3.4% annualised in 2Q23, well below the 2018-19 average of 6.3%.

The July official manufacturing PMI data, which showed a second consecutive monthly recovery, suggest the worst of the deceleration is probably over. However, growth momentum remains subpar.

In addition to the slowdown in exports and domestic demand, the marked weakness in 2Q23 was also driven by a reduction in inventories – a factor that is less discussed.

After the COVID outbreak in 2020, real industrial inventories of finished goods accelerated meaningfully in late 2021, as industrial firms turned more optimistic about the outlook: exports have enjoyed a robust upswing thanks to post-pandemic-driven demand, while property sales also saw a strong revival thanks to pent-up demand when sentiment around housing investment has not yet changed.

But following last year’s repeated lockdowns, the growth rate of industrial inventories started decelerating in late 2022, and even more sharply in 2Q23, as industrial firms shifted from passive inventory accumulation to active destocking.

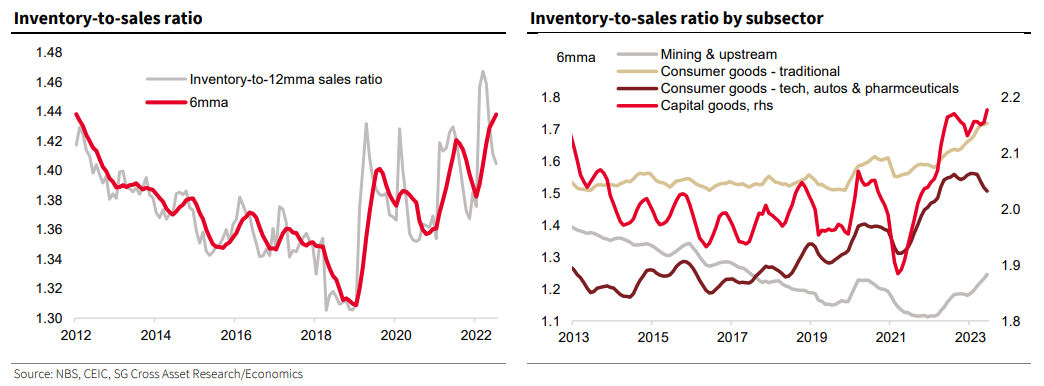

To ascertain whether inventories are being reduced to an optimal level, we compare the current nominal inventory-to-sales ratio to the historical average.

For the industrial sector as a whole, the ratio has risen to above 1.40 months from an average of 1.34 months in 2017-19, a period following the supply-side reform where the level of inventories was considered optimal, with the caveat being that the property sector was then still in its prime.

This suggests that the inventory reduction probably still has some way to go given that sales are not expected to recover materially in the near term.

That said, the plunge in inventory growth in 2Q from 5.8% in 1Q to -0.1% doesn’t seem likely to persist either given that the inventory index in the manufacturing PMIs have begun to stabilise lately.

Assessing the level of inventory across different industries using the same metric, we note that upstream sectors seem to have the least destocking pressure and capital goods the most, while consumer goods are somewhere in between.

• The inventory-to-sales ratio of the mining and upstream industry, although it has picked up, remains below the levels seen in early 2010s when China was battling oversupply problems in the upstream sectors. That means the metals sector at least is not facing strong destocking pressure. The ‘glass half full’ view would be that these sectors have done much of the adjustment needed in response to structurally slow growth in construction demand.

• In contrast, the capital goods industry has continued to see the highest inventory-to-sales ratio, which picked up from 2.0 months in 2017-19 to 2.2 months in 1H23. After the pandemic, manufacturing fixed asset investment saw strong growth of 13.5% in 2021 and 9.1% in 2022. That poses the question of whether the industry is experiencing excesses, as evident in the solar powerindustry.

• Regarding consumer goods, both traditional and high-tech products have seen increased inventory ratios. Computer and electronic products have seen a large build-up of inventories, similar to what we observe globally, because of concerns over the supply chain previously and now normalising consumer demand. The reduction process has started, and we expect that to continue in 2H23, but restocking looks likely in 2024 if external demand stabilises and consumption continues to recover as expected. That should help to stabilise industrial sector momentum.

I have mentioned the destocked iron ore supply chain many times. This is some protection against dramatic price moves.

Nonetheless, I believe the developing underlying weakness in demand is so severe that fundamental, not apparent market balance will drive prices lower in due course.

Excess downstream inventories can contribute to this.