This week saw the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) go against the predictions of most economists and the financial market by lifting the official cash rate (OCR) another 0.25% to 3.85%.

In coming to its decision, Governor Phil Lowe said the Bank is especially worried about ‘sticky’ services inflation, noting it “is still very high and broadly based and the experience overseas points to upside risks”.

The 3.75% of interest rate tightening over the past 12 month has lifted variable mortgage repayments by around 50%, placing many borrowers under financial distress.

Two other major advanced economies also lifted official interest rates this week.

The US Federal Reserve lifted the federal funds rate by 25 basis points, as expected, to a target range of 5.00%-5.25%.

It is now at the highest level since August 2007 and was the Fed’s tenth consecutive rate increase since March 2022.

However, in its statement the Fed altered its policy forward guidance to suggest it could either hike or pause interest rates in June. Although Fed Chair Powell also played down the likelihood of looming cuts.

The European Central Bank (ECB) also hiked its benchmark policy rates by 25 basis points, with the deposit rate lifting to 3.25%.

ECB President Christine Lagarde remained hawkish saying “we are not pausing – that is very clear” and “we know that we have more ground to cover”.

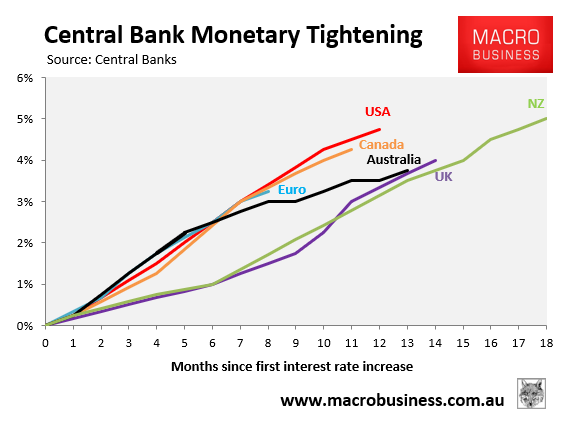

The below chart shows the interest rate “race” across the major Anglosphere nations and Europe:

New Zealand remains way ahead, whereas Australia is middle of the pack.

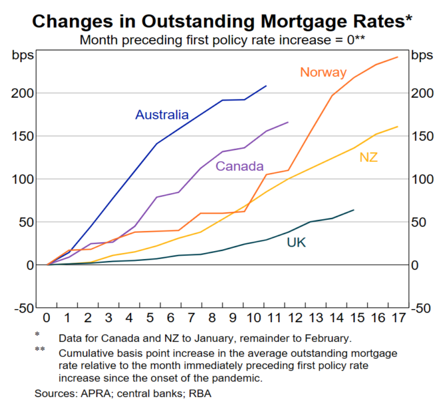

However, the below chart from the RBA shows the rise in mortgage rates in Australia has been more severe than most other developed nations:

Average mortgage rates in Australia have risen by approximately 210 basis points, compared to around 160 basis points in New Zealand.

According to Phil Lowe, Australia’s larger mortgage rate increase is due to “the predominance of variable-rate mortgages” which “means this is a more powerful transmission mechanism of monetary policy than in many other countries”.

The majority of mortgages in New Zealand have fixed interest rates.

Home loans in the United States are normally set for the entire loan term of 30 years, which is why the country isn’t even included in the RBA chart shown above.

As a result, mortgage holders in most other countries are not impacted to the same extent as Australians when official interest rates increase.

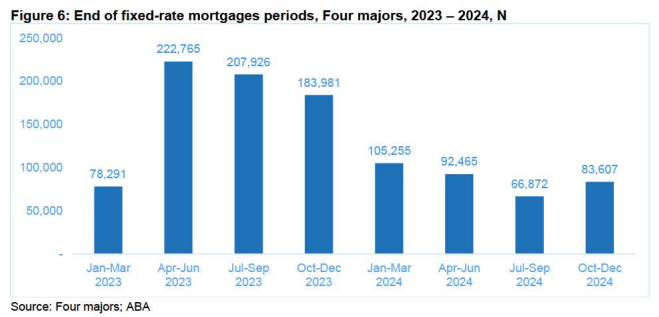

Australia’s monetary policy transmission will also accelerate over the remainder of this year as hundreds of thousands of cheap fixed rate loans expire:

Even if the RBA does not lift rates any further, there is substantial monetary tightening ‘built-in’ due to the fixed rate “mortgage cliff”.