I wanted to follow up on Jeremy Grantham’s comments from yesterday and run through some of GMO’s asset allocation views from the perspective of an Australian investor.

Jeremy Grantham & Co. at GMO have put out two thoughtful (as always) pieces in the last 3 weeks. I rate the team there highly and so when I have a different view I take that as a sign that I need to go back and triple check all of my assumptions.

Article 1

In late December we got the latest quarterly, which was full of hand-wringing over what to buy when everything is expensive. Which I have a lot of sympathy for, trying to deal with the same issues.

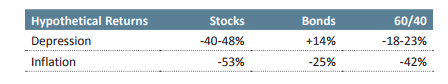

First Ben Inker considers a depression scenario and an “inflation problem” scenario and the effect that he thinks each would have on a portfolio – neither are pretty:

He also looks at other assets which could save you and settles on emerging market equities as the winner.

To be clear, our fondness for emerging equities today is driven overwhelmingly by their cheaper valuations, not a speculative belief in their resilience against an event that has not occurred since emerging became an institutionally buyable asset class. But if worse did come to worst and inflation flared up, owning a good chunk of the only equities that remember what inflation is like seems like a decent idea.

Then Jeremy Grantham puts in his view:

Inside GMO there are three different views on whether and how rapidly the market will revert to its pre-1998 normal:

- James Montier feels it will be business as usual and revert within 7 years. Ben Inker also holds out for a 7 year period, but includes a 33% chance it will revert to a higher average valuation (the “Hell” scenario). I believe that the reversion on valuations will take 20 years, and that profit margins will probably only revert two-thirds of the way back to the old normal.

- All three outcomes are quite possible. This creates a difficult investment challenge.

- My proposition, though, is that there is an optimal investment for all three outcomes: a heavy emphasis on Emerging Market (EM) equities, especially relative to the US.

- To concentrate the mind, I fantasize about managing Stalin’s pension fund where the penalty for failing to deliver 4.5% real per year over 10 years is death. I believe only a very large investment in EM equities will give an excellent chance of survival.

He also highlights early-stage venture capital as being an opportunity.

There is a lot more to it, covering themes that we express here on this blog and that we spend a lot of time internally debating as well – mainly what tail risks are there, how likely are the outcomes and over what time frame will the themes play out.

Article 2

Last week, Jeremy then published his “Bracing Yourself for a Possible Near-Term Melt-Up (A Very Personal View)” piece:

I find myself in an interesting position for an investor from the value school. I recognize on one hand that this is one of the highest-priced markets in US history. On the other hand, as a historian of the great equity bubbles, I also recognize that we are currently showing signs of entering the blow-off or melt-up phase of this very long bull market. The data on the high price of the market is clean and factual. We can be as certain as we ever get in stock market analysis that the current price is exceptionally high. In contrast, my judgment on the melt-up is based on a mish-mash of statistical and psychological factors based on previous eras, each one very different, so that much of the information available is not easily comparable.

Grantham highlights that he (and another notable bubble expert, Robert Shiller) can’t see the signs that stock markets are overheated and euphoric.

Grantham highlights the advance/decline line as being one of the signs in the past, and that this is not delivering threatening messages.

Summary of my guesses (absolutely my personal views)

■ A melt-up or end-phase of a bubble within the next 6 months to 2 years is likely, i.e., over 50%.

■ If there is a melt-up, then the odds of a subsequent bubble break or melt-down are very, very high, i.e., over 90%.

■ If there is a market decline following a melt-up, it is quite likely to be a decline of some 50% (see Appendix).

■ If such a decline takes place, I believe the market is very likely (over 2:1) to bounce back up way over the pre 1998 level of 15x, but likely a bit below the average trend of the last 20 years, as the trend slowly works its way back toward the old normal on my “Not with a Bang but a Whimper” flight path.

Our interpretation

There is a lot in here, I’ll give a quick summary of our view and follow up more on these in later posts. Overall we have broad agreement with the views and market assessment – but we differ in a few key areas:

Inflation vs deflation

Ben is right that if runaway inflation becomes a problem, then every asset (excluding cash and inflation-linked bonds) are in trouble.

We contend that runaway inflation is unlikely to be the case, that rebalancing in China away from capex will constrain commodities, increasing inequality will constrain demand and generally high government debt levels will constrain fiscal expenditure.

Our portfolio is positioned for the opposite. There are risks, but our view is that low inflation is still the enemy. This inflation will be masked for a few years by Trump tax stimulus and the recent rise in oil prices, but until inequality reverses we do not expect any sustainable demand increase.

If you were equally worried about all scenarios, we can see why you would reach Ben’s conclusion. And over the next few years, we very well may see a spike in US inflation – it seems that Trump is trying to engineer a boom at a time of close to maximum employment after all. Our view is that this will be cyclical (i.e. a medium-term outcome) though rather than structural.

AUD Effects and Melt-up

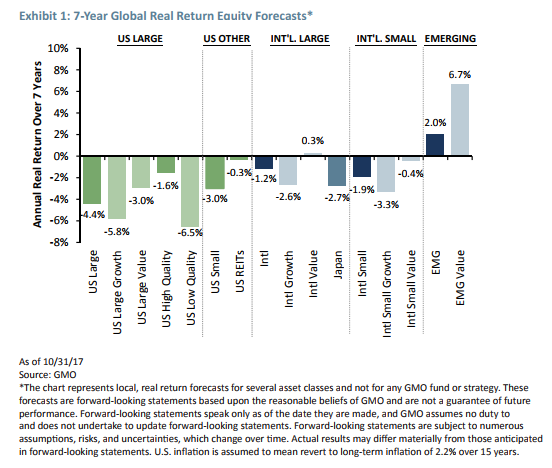

We run a similar model to GMO when looking at long-term asset values. Here is GMO’s outlook:

In a relative sense, excluding emerging markets, we have a similar outlook. Our view is that a mix of international quality and value offers far and away the best returns at the moment. We also struggle to find US equities that are worth buying.

The main differences we have in our portfolio (excluding emerging markets which is covered below) are:

- Currency. We are investing in Australian dollars (GMO are investing from a USD perspective), and so at the end of historically high mining and housing booms, the risk is to the downside. The end result of the twin booms is that Australia is expensive to business in due to high rent, high energy prices and high wages. We also hollowed out our manufacturing sector. All these add up to the Australian dollar needing to be lower to restore competitiveness. The Australian dollar also provides us with a useful hedge that the GMO doesn’t have when investing in USD.

- Timeframe. Our portfolios are sided with Jeremy on both the reversion to the mean and the melt up. Central bank action and the preponderance of the “extend and pretend” approach to debt crises suggests no quick resolution and so we are expecting a slower reversion to the mean in the long term. In the short term its hard to see any impediments to the market rising though. So we are cautiously long international, with an eye to many of the signs that the market is reaching the end game as a signal to wind back our equity exposures. But we agree that it is not yet time to get out of the stock market.

Emerging markets

There will be stocks that will perform well in emerging markets. I don’t like the blanket buy of emerging markets from GMO though.

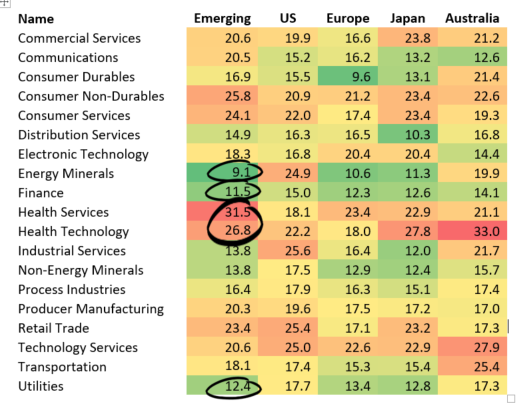

First, I don’t think emerging markets are as cheap as GMO proport. At a headline level, emerging markets look cheap, but dig deeper and it is not true:

12 month forward Price / Earnings BY SECTOR/REGION

Energy materials are cheap in emerging markets. How many Russian energy stocks would you like?

Finance stocks are cheap in emerging markets. How many Chinese banks would you like to own?

Utilities are cheap in emerging markets. Are you looking for a chance to buy government-regulated assets in 3rd world countries, dependent on the whim of leaders who want to keep electricity prices artificially low? Be my guest.

Flip to a sector that everyone wants to own. A growing middle class in China and India will be great for health care going forward. But these stocks are some of the most expensive stocks in the world, so be prepared to pay up for the privilege. They aren’t cheap.

And that is before we look at Chinese state-owned enterprises – these are some of the largest companies in emerging market indexes, and so they trade at a discount because they answer first to the Chinese government before they answer to shareholders. Take these out and some of the average-priced emerging market sectors above start to look expensive.

Finally, as a general trend, I’m expecting robotics and automation to mean that (at the margin) more manufacturing is done in developed markets in coming years.

Summary

While I spent most of this post talking about the differences in our view, the reality is that I’m more heartened by the similarities in our outlook than I am concerned about the differences.

Australian investors face a different set of risks, and so need a different allocation.

Damien Klassen is Head of Investments at the Macrobusiness Fund, which is powered by Nucleus Wealth.

The information on this blog contains general information and does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Past performance is not an indication of future performance. Damien Klassen is an authorised representative of Nucleus Wealth Management, a Corporate Authorised Representative of Integrity Private Wealth Pty Ltd, AFSL 436298.