From the Bank of International Settlement’s quarterly review:

Investors increasingly focused on growing vulnerabilities in emerging market economies (EMEs), particularly China, as they reassessed the global growth outlook. In China, equity markets plunged following a prolonged surge in stock prices that had propelled many stock valuations to extreme levels. This dented investor confidence and weighed on asset prices globally.

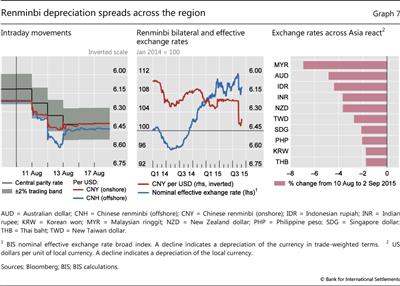

The Chinese authorities’ decision in August to allow the renminbi to depreciate against the dollar gave markets a renewed jolt. The move intensified investors’ concerns about growth prospects for China, EMEs more broadly and, ultimately, the global economy. As a result, a number of currencies came under further pressure, particularly in Asia. With Chinese equities resuming their plunge in the second half of August, risky assets sold off across the globe and implied volatilities spiked up across asset classes.

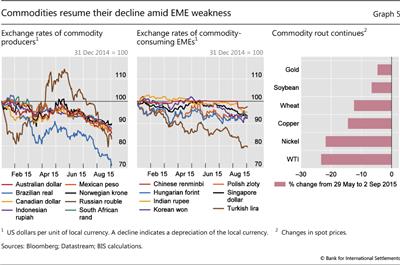

Amid extreme volatility, commodity prices, led by oil, resumed their downtrend after a brief hiatus in the second quarter of 2015. Perceptions of falling demand due to weakening economic activity in a range of EMEs most likely played a key role, although strong supply helped to undermine oil prices. In turn, falling commodity prices further hurt the growth outlook for commodity-producing EMEs. As a result, many commodity producers saw renewed depreciation of their exchange rates, which was exacerbated by another episode of dollar strengthening resulting from the US monetary policy outlook.

In government bond markets, yields edged back down after sharp increases in April and May, remaining at levels not far from the troughs reached in early 2015. This reflected a combination of unusually low, if not negative, term premia and expectations that interest rates would move up only slowly and moderately in coming years. Hedging behaviour on the part of insurers and pension funds, coupled with investors reaching for higher returns further out on the yield curve, added to the downward pressure on long- term yields.

Markets roiled as China jolts investors

Global financial markets have suffered repeated blows over the past few months, with a number of them due to events in China. On the heels of the Greek crisis, markets were roiled following a sharp drop in the Chinese equity market and a surprise change to the renminbi’s exchange rate arrangements.

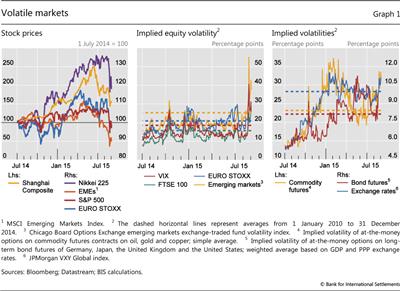

Markets, particularly in Europe, hit turbulence early in the quarter as negotiations about renewed funding for Greece dragged on. This was behind much of the underperformance of European equities, which caused the EURO STOXX index to fall by almost 11% between end-March and early July (Graph 1, left-hand panel).

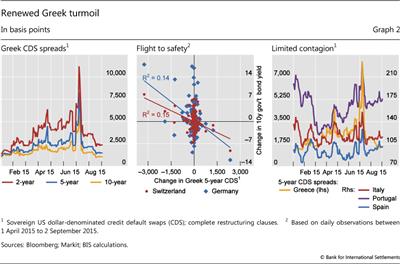

The drawn-out negotiations between Greece and its creditors through the first half of 2015 gradually undermined market sentiment. As the situation reached crisis proportions, with the banking system closed down and capital controls in place, two-year Greek sovereign credit default swap (CDS) spreads peaked above 10,000 basis points in early July, after voters rejected proposed reforms in a referendum (Graph 2, left-hand panel). Financial markets beyond Greece were also affected. In bond markets, there were clear signs of flight to safety as, for example, German and Swiss bond yields fell on days when Greek CDS widened the most and recovered on days when spreads tightened considerably (Graph 2, centre panel). Although the ongoing Greek crisis weighed on investor sentiment, the direct contagion to other periphery euro area sovereigns was limited and short-lived. Five-year sovereign CDS for Italy, Portugal and Spain, for instance, rose only by some 30-60 basis points in the course of the second quarter (Graph 2, right-hand panel). Eventually, as it became likely in early July that a new programme for Greece would be forthcoming, markets quickly recovered and investors started to turn their gaze elsewhere.

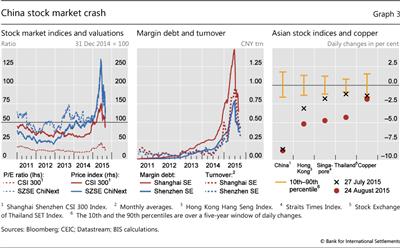

China’s situation, in particular, received increasing market attention as the country’s equities fell sharply in late June and early July. Following a spectacular surge lasting over a year, the benchmark Shanghai Shenzhen CSI 300 Index lost almost one third of its value between 12 June and 8 July (Graph 3, left-hand panel). The adjustment was even more dramatic for the Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE) ChiNext small technology company index, which plunged by 40% over the same period.

The preceding run-up in Chinese equity prices was driven by increased trading activity and a build-up of leverage, which accelerated as the central bank eased monetary policy (Graph 3, centre panel). Combined daily turnover averaged CNY 1.8 trillion ($300 billion) in the month up to 12 June, around six times the 2014 average and exceeding that of the US stock market. This was fuelled by over 56 million new trading accounts opened predominantly by retail investors in the first half of 2015. Broker-intermediated margin trading reached CNY 2.2 trillion ($360 billion) in early June, an almost sixfold increase from the year before, representing approximately 8% of tradable market capitalisation. Increased leverage went hand in hand with rising valuations: the CSI 300 price/earnings ratio went up from 10 in mid-2014 to 21 in June 2015, while the P/E ratio on the ChiNext exchange peaked at 143 (Graph 3, left-hand panel). Turnover and leverage then plunged, reflecting new regulatory curbs and the rapid retreat of retail investors.

As concerns over Chinese equity market fundamentals persisted and authorities began scaling down their market-supporting measures, the volatility increasingly spilled over to other markets, especially in Asia. On 27 July, when the CSI 300 Index fell by 8.5% – its largest daily drop since 2007 – equity markets across Asia, and some commodity prices, suffered outsize drops (Graph 3, right-hand panel). In late July and early August, equity prices in China and elsewhere briefly stabilised.

This respite was short-lived. Concerns about China’s growth outlook took centre stage as the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) on 11 August announced major changes to its foreign exchange policy (see detailed discussion below). While the measures were officially described as a step towards a more market-oriented foreign exchange mechanism for the renminbi, the resulting depreciation was seen by some as a sign that Chinese growth was expected to weaken further. Currencies in the region and beyond depreciated sharply in response to the weakening of the Chinese currency. As price drops in commodity markets accelerated, investors grew increasingly concerned about growth prospects for EMEs more broadly, and the impact on the global economy.

When Chinese equity prices began to fall sharply again in late August, global equity indices plummeted. Between 18 and 25 August, while Chinese equities slumped by another 21%, the world’s major equity indices dropped by around 10% (Graph 1, left-hand panel). The S&P 500 Index closed 4% down on 24 August alone (a day when the CSI 300 Index fell by almost 9%; see Graph 3, right-hand panel), after a 6% slide during the day, amid intraday stock price drops of more than 20% for blue chips such as GE and JPMorgan Chase.

Against this backdrop, implied volatilities shot up: the VIX index surged to 40, its highest level since 2011, while EME implied equity volatility (VXEEM) rose the most on record (Graph 1, centre panel). Rising volatility was not confined to equities: commodity, bond and foreign exchange market volatility all spiked to levels much above post-crisis averages (Graph 1, right-hand panel).

By the start of September, the global equity market sell-off brought the Datastream world P/E ratio back down to just below its median value since 1987. Global P/E ratios had breached this median value in early 2015, after their upward trajectory since 2012.

Strong dollar and commodity plunge add to EME weakness

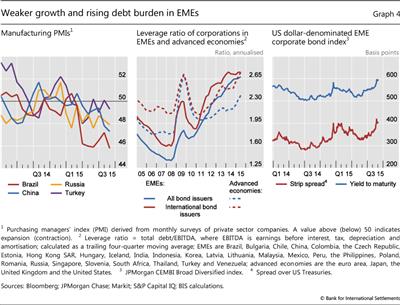

China’s economic slowdown and the US dollar’s appreciation have confronted EMEs with a double challenge: growth prospects have weakened, especially for commodity exporters, and the burden of dollar-denominated debt has risen in local currency terms. According to one indicator, China’s private sector manufacturing activity contracted at its fastest pace in six years in August, while the purchasing managers’ index (PMI) in Brazil, Russia and Turkey remained at or below 50 amid adverse country-specific developments (Graph 4, left-hand panel). In this environment, EME corporations, after ratcheting up their income-based leverage to the highest levels in a decade (Graph 4, centre panel), saw sharply rising credit spreads (Graph 4, right-hand panel). The depreciation against the US dollar of most EME currencies, including those of both commodity producers and consumers, added to the difficulty of servicing the dollar-denominated part of this debt (Graph 5, left-hand and centre panels).

After a brief but sizeable recovery in the second quarter of 2015, the prices of most commodities continued their plunge (Graph 5, right-hand panel), putting additional pressure on commodity producers’ exchange rates. Perceptions of weaker global demand due to the fall in China’s investment growth and, in the case of oil, persistently high supply played a key role.

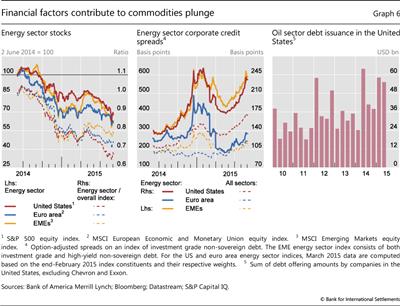

Financial factors, too, may have contributed to the commodity plunge. The fall in the dollar oil price can be partly explained by the appreciation of the US dollar, which in the absence of such a decline makes oil more expensive outside the United States. Despite falling stock prices and rising borrowing costs (Graph 6, left-hand and centre panels), the US energy sector stepped up its debt issuance, possibly in an effort to defend market share (Graph 6, right-hand panel). High debt burdens may force these firms to keep up their production simply to generate the cash flow they need to service their debt, accentuating the downward pressure on oil prices.

Against this backdrop, a number of emerging market economy and commodity-exporting advanced economy central banks eased monetary policy, including those of China, Hungary, India, Korea, Russia and Thailand as well as Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Norway. In Brazil, where a recession coincided with rising inflation and political tensions, the central bank increased its key policy rate from 12.75% in early March to 14.25%, citing above-target inflation as its primary concern, but signalled a pause in further tightening.

As emerging market currencies sagged against the dollar, the PBoC on 11 August announced major changes to its foreign exchange policy. The renminbi would continue to trade against the US dollar in a ±2% daily band, but the central parity around which the band is set would be determined by the previous day’s closing market rate rather than a preset target rate. This more market-oriented mechanism is a step towards fulfilling the criteria for the renminbi’s inclusion in the IMF’s SDR basket ahead of its review in late 2015.

This change led to further ructions in the foreign exchange markets. The renminbi slipped by 2.8% against the US dollar in the two days after the surprise announcement, before stabilising when the PBoC intervened to support the currency (Graph 7, left-hand panel). From the start of 2015 up to the introduction of the new fixing method, the renminbi had traded consistently towards the weaker end of the trading band, pointing to some depreciation pressures as the stable bilateral exchange rate against the US dollar led to a sizeable renminbi appreciation in trade-weighted terms (Graph 7, centre panel). Emerging Asia currencies reacted strongly, with the Malaysian ringgit depreciating by more than 6% since the announcement (Graph 7, right-hand panel). On 20 August, Kazakhstan, a commodity exporter whose main trading partners are Russia and China, announced that it would let its currency trade freely; the Kazakhstan tenge immediately lost more than a fifth of its value against the US dollar.

Diverging monetary policies continue to drive markets

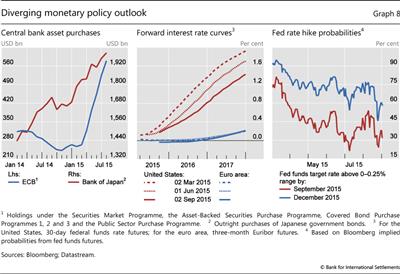

Diverging monetary policies have continued to be an important driver for markets over the past few months. With policy rates close to zero, the Bank of Japan and the ECB continued their respective asset purchase programmes, seeking to stimulate economic activity and lift inflation closer to target (Graph 8, left-hand panel). At the same time, the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England continued to prepare market participants for an eventual increase in their policy rates.

In particular, the Federal Reserve’s efforts in this direction have been ongoing for some time, thus keeping US forward interest rates persistently above those in the euro area and elsewhere (Graph 8, centre panel). But macroeconomic upsets and bouts of market turbulence have prompted investors to scale back their expectations for near-term rate hikes. For example, whereas prices of federal funds futures contracts at the beginning of 2015 implied an 80% probability that the target rate would have been raised by September, and a 90% probability that it would have happened by December, these probabilities had fallen to around 32% and 58%, respectively, by 2 September (Graph 8, right-hand panel). These estimated probabilities dropped sharply twice during the quarter. On 8 July, they fell to 21% and 54%, respectively, shortly after the Greek referendum and on a day when the Shanghai equity index plummeted by 6%. After recovering in subsequent weeks, they again slid in late August following the extreme turbulence in global equity markets.

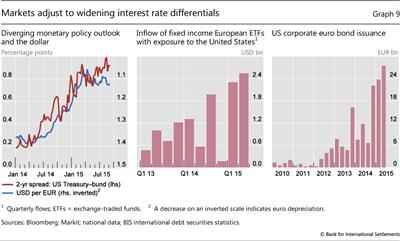

Although the timing of the Federal Reserve’s first move has become more uncertain, interest rate differentials between the United States and many other countries have remained wide, with important consequences for foreign exchange markets. In particular, except for a brief hiatus in the second quarter of 2015, the US dollar has been on an appreciating trend since mid-2014. The influence of interest rate differentials on the dollar was particularly stark with regard to the euro: as the difference between US and core euro area interest rates began to widen again in the third quarter of 2015, the dollar resumed its strengthening path against the euro (Graph 9, left-hand panel). Towards the end of the period, as US short-term rates edged down, the euro recovered somewhat.

Interest rate differentials also affected the behaviour of investors and borrowers. With interest rates at or near record lows in the euro area, fixed income investors increasingly turned to higher-yielding dollar assets. For example, flows into European exchange-traded funds linked to US bonds surged. In the first half of this year, such flows amounted to $4.8 billion, as compared with $4.0 billion in the entire year of 2014 and $3.4 billion in 2013 (Graph 9, centre panel). For their part, firms in the United States increasingly issued euro-denominated debt to benefit from the low borrowing costs. In the second quarter of 2015, total gross issuance of euro-denominated debt by US non-financial corporations amounted to €30 billion, surpassing even the brisk issuance of the previous two quarters (Graph 9, right-hand panel; see also “Highlights of global financing flows“, BIS Quarterly Review, September 2015). With ongoing ECB asset purchases weighing on the yields of core euro area government debt, yield-starved European investors have welcomed the rising supply of corporate debt.

Straight outta the MB playbook. The BIS is an excellent organisation, predicted the GFC and is right on the money again.