Why Australian house prices don’t make sense

Australian housing has never been this expensive.

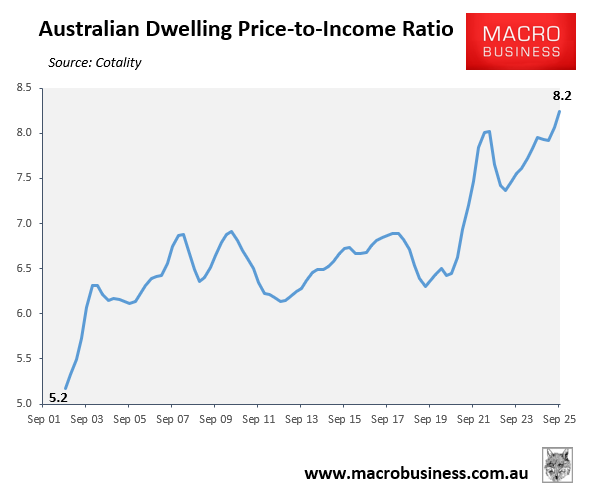

According to Cotality’s latest housing affordability report, the nation’s median dwelling price was valued at a record 8.2 times median household income in the September quarter of 2025, up from 6.4 times the median income in the September quarter of 2019.

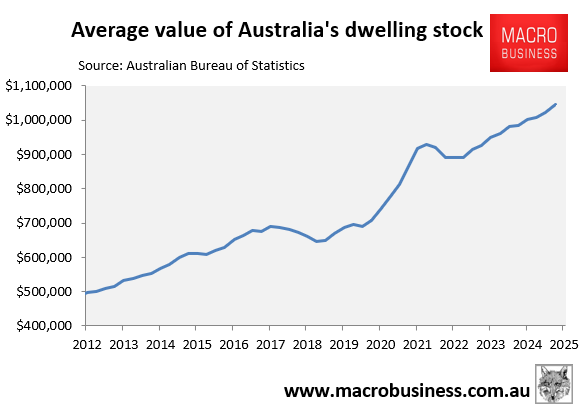

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) also valued the average dwelling at a record $1,045,000 as of the September quarter of 2025, up from $668,800 as of the September quarter of 2019.

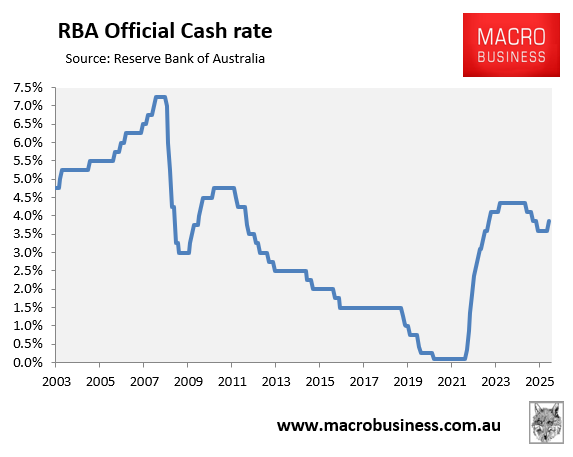

The most curious aspect of Australia’s housing market is that prices rose strongly despite the official cash rate soaring by a record 4.25% from May 2022 before falling back slightly to 3.85% currently.

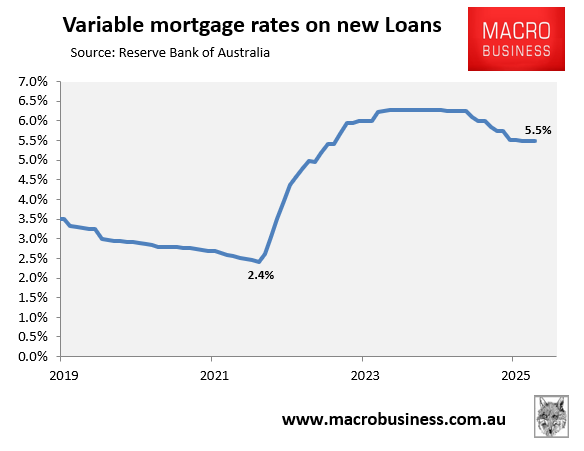

Over this period, Australia’s discount variable mortgage rate soared from a low of 2.4% in April 2022 to a peak of 6.25% between November 2023 and January 2025 before falling to 5.5% following last year’s three 0.25% rate cuts from the RBA.

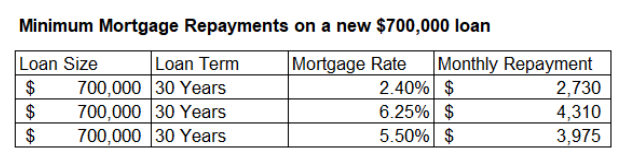

The impact of this rise in mortgage rates is illustrated in the table below, using the average new loan size of $700,000:

When variable mortgage rates bottomed out at 2.4%, the minimum monthly repayment was only $2,730 per month.

At the peak between November 2023 and January 2025, when the average variable mortgage rate on new mortgages hit 6.25%, the minimum monthly repayment on a $700,000 loan was $4,310, an increase of $1,580 or 58%.

After mortgage rates fell to 5.5% following last year’s rate cuts from the RBA, the minimum monthly repayment on a $700,000 loan was $3,975, still $1,245, or 46%, above the pandemic low.

Normally, one would expect that the dramatic rise in mortgage repayments and the circa 30% reduction in borrowing capacity would have sent house prices falling.

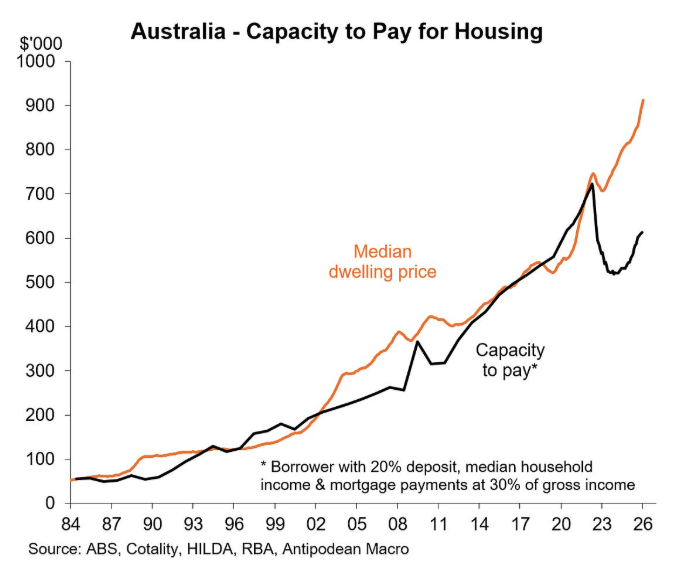

After all, for most of the past 30 years, Australian house prices have closely tracked borrowing capacity, because buyers bid with the maximum the bank will lend. When rates fall, borrowing power rises and prices generally rise; when rates rise, borrowing power falls and prices usually soften.

However, as illustrated below by Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro, the relationship has broken down and a record gap has developed between borrowing capacity and house prices:

There are a few likely explanations for why such a gap has developed.

First, the ‘Bank of Mum and Dad’ has become a massive and rapidly growing informal lender in the housing market. It is commonly regarded as the nation’s fifth‑largest mortgage lender, contributing between $35 billion and $92 billion annually to help children buy property.

Hillhouse Legal Partners estimates that the Bank of Mum and Dad is now used by 2 in 5 first‑home buyers, with deposits funded by parents bypassing borrowing limits.

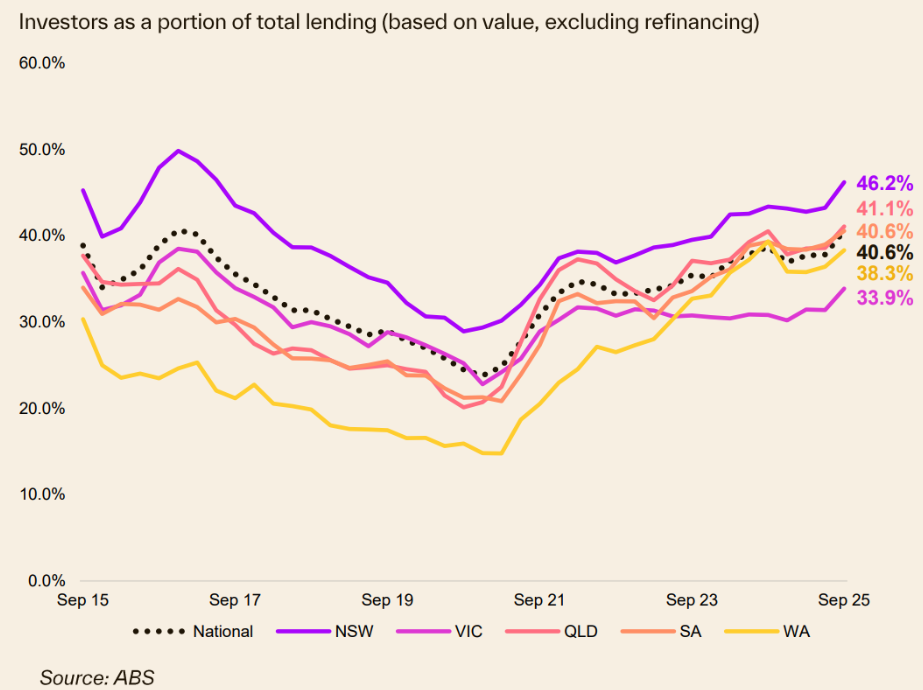

Second, as illustrated below by Cotality, the share of investors in the market has significantly increased.

Since investors generally borrow against existing housing equity, they can bypass traditional limits on borrowing capacity.

Finally, government incentives like shared equity schemes, home buyer grants, and 5% deposit schemes reduce the impact of borrowing constraints and artificially boost demand in specific price bands.

As a result, Australian home values have experienced a record decoupling from borrowing capacity.

With the RBA tipped by financial markets to raise the official cash rate two more times, this implies that borrowing capacity will shrink as variable mortgage rates rise back to their recent peak of 6.25%.

Futures market cash rate pricing

Whether this shrinkage in borrowing capacity triggers price falls remains to be seen.

Eventually, however, prices and borrowing capacity will need to fall back in line.

Only then will Australian housing valuations make sense.