There will never be a better time for budget and economic reform

All of a sudden, the planets have aligned. Something both sides of Australian politics have been able to shunt off into the ‘politically too hard’ basket for much of a generation is now eminently doable.

All that is required is data, some integrity in interpreting that data, and the political cojones to stand and deliver.

Even more auspiciously, the time has come for the socio-economic paradigms of the last couple of generations.

Expanding access to debt delivers no aggregate benefit for the country; continuing to privatise public assets simply risks the creation of more rentier positions in the public for the well-heeled to invest in.

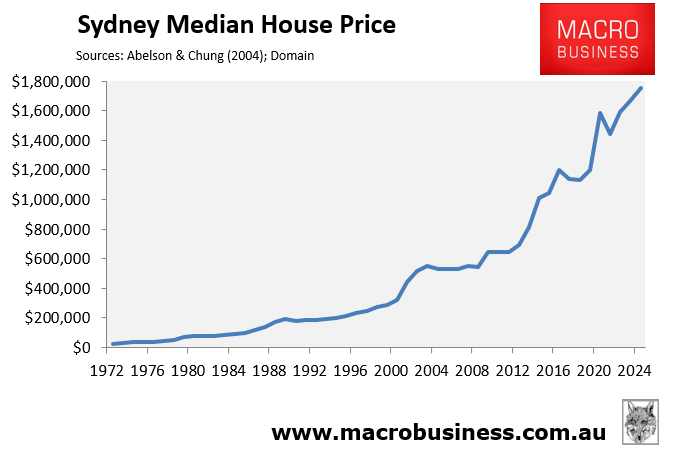

House prices have already gone a bridge too far to be a concept that could keep future Australia onside; citizenship sales through the education and visa system are now simply an investment in mounting social discontent.

The sun is setting on the mining and commodities boom, which underpinned a generation’s wealth while eviscerating the national economic base.

The public spending started during Covid has reached conspicuous levels, leading to mounting calls for governments to visit Weight Watchers.

After all that, Mr Donald J Trump has shoved a cactus up the jaxi of neoliberal free trade. And even if he disappears into history in three years’ time, getting the prickles out will take some time, and a degree of transnational froideur can be expected to remain.

In that context, Australia has offshored almost everything except services, which still need to be provided by people in person.

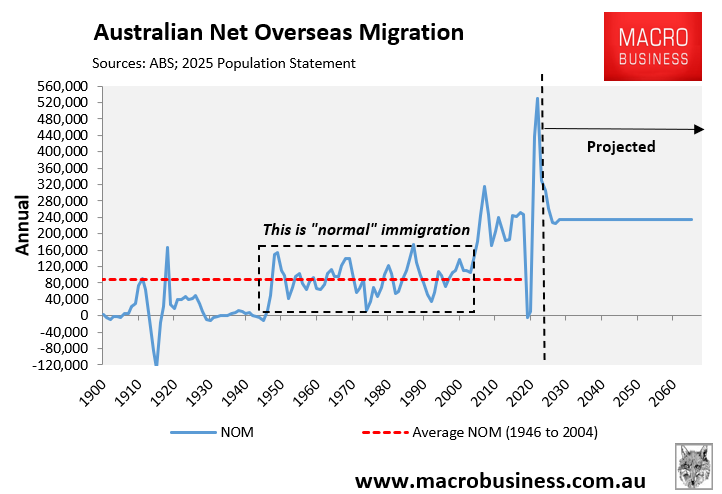

If Australia cannot convince anyone to utilise Australians en masse to earn an income, then the entire basis for the immigration volumes we have must be questioned.

For Australian budget reform and the economic reform that has to come with it, the time has come.

You can smell it in the air, and you can hear it on the streets. But the best gauge of it is the number of pieces being slipped into our discredited mainstream media, arguing for someone else’s patch to be reformed. The beneficiaries of a couple of generations’ worth of economic policy are starting to fret that, in the late 2020s, they too might be reformed.

That actually makes it a good thing that Albo and the ALP are in government and that the Federal Liberal Party has taken a leaf out of their Victorian counterpart’s playbook on the path to political irrelevancy.

The only real economic reform in Australian history comes from the ALP side—Hawke-Keating, Whitlam and Chifley. He has a majority in Parliament, which should be cementing thoughts of historical legacy. And his own chief economic architect stated the core requirement just weeks after the resounding whooping of the last federal election.

“So much of the democratic world is vulnerable because governments are not always meeting the aspirations of working people.

We have a responsibility here and an obligation.

A responsibility to rebuild confidence in liberal democratic politics and economic institutions – by lifting living standards for working people in particular.

And an obligation to future generations to deliver a better standard of living than we enjoy today.

That’s really why productivity matters, why budget sustainability matters, why resilience in the face of global turmoil matters –

It’s why reform matters”.

Ordinary Australians living in the suburbs of our major cities and in towns blighted by cost-of-living pressures can only wait while a government with time to play with decides what it stands for when it comes to socioeconomic reform.

While the rest of the media space is out there trying to nudge that reform away from vested interests, at Macrobusiness, the need for reform across the spectrum is profoundly obvious.

While various opinion leaders and institutions talk about budget repair, at Macrobusiness, we note that while budget repair is indeed essential, there can be no budget repair—especially in a nation as reliant as Australia is on commodity exports produced by about 3-5% of the population—without major economic reform.

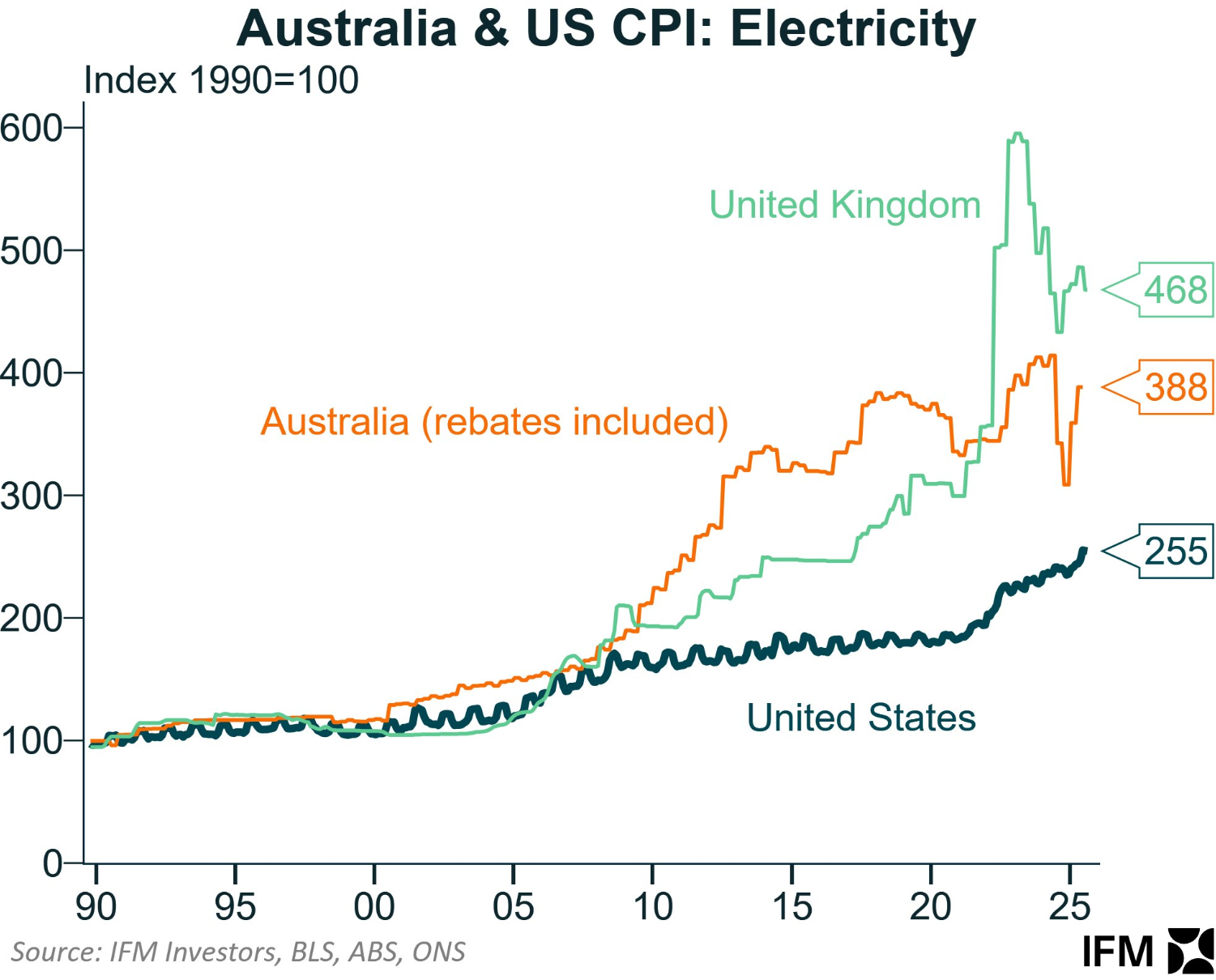

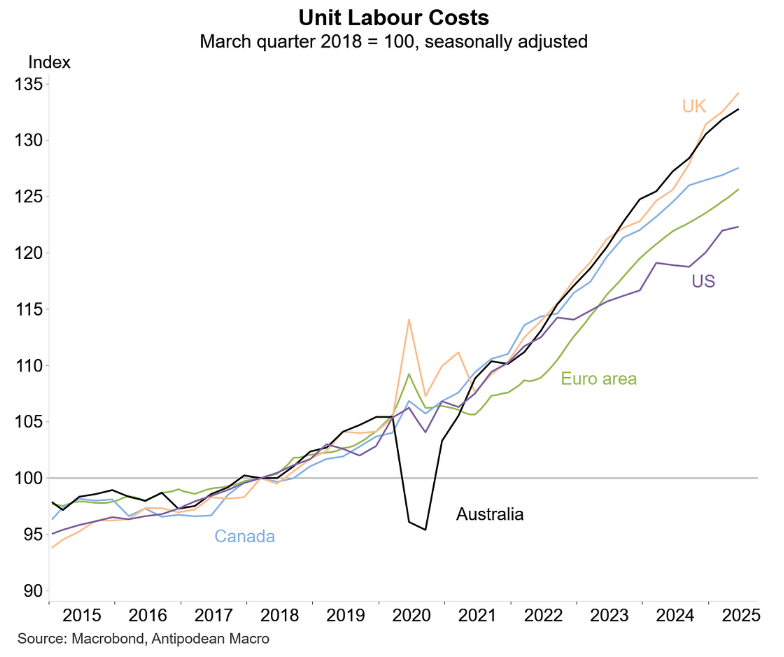

While any given piece about economic reform starts at implying ordinary people are expensive and need to become ‘cheaper’ for business, and that business is festooned in ‘red tape,’ at Macrobusiness, we have been stating for nearly a generation that Australia’s economic diversity tide was ebbing, while everyday Australians were being baked on a beach with amongst the world’s most expensive land costs, energy costs, and internet costs, made more expensive with a currency inflated by commodity exports.

That observable dynamic means Australians are primarily employed and engaged in inward-facing sectors of the economy, addicted to public sector or government-funded employment, and government funding for customers of businesses everywhere, with Australia’s private sector essentially about harvesting an ever-increasing number of bums on seats made possible by the population Ponzi.

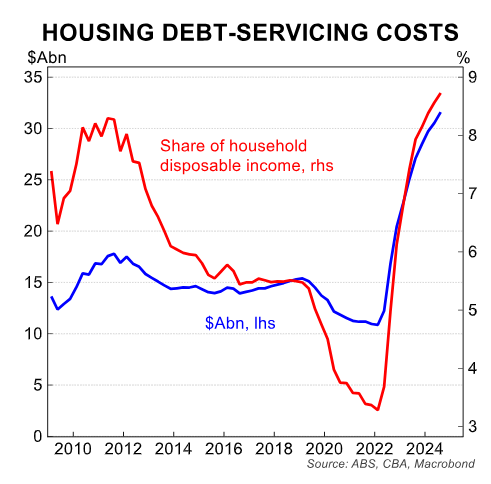

While that model has sustained aggregate demand, it has incurred a disproportionately heavy cost at a per capita, or individual level, where ordinary everyday Australians are heavily in debt, reliant on crowded infrastructure, and have experienced more than a decade’s worth of stagnant income growth while the RBA is telling us that costs are not under control and now haven’t been since well before Covid hit.

The upcoming May budget will have to fire the gun to overtly reform Australia’s socioeconomic status and set the tone and direction for where that reform takes us as a nation and hand over to future Australia.

Macrobusiness welcomes that because economic and budget reform is the only way that all Australians are going to get a better economy and hand that over to future Australians.

Amongst the major issues Australia’s economic and budget reform process will have to address are:

- Housing, land, and business site costs: How big are they as an international comparison? How big a factor are they for Australian externally exposed businesses? How big a factor are they for Australian employees as a driver of labour market dynamics?

Australia has more land per capita than just about any other nation on earth. There is no fundamental reason why Australians are shoehorned into tiny blocks of land costing them ridiculous rents or mortgages and why those same rents and land costs affect any business.

The only reason is government policy over generations to make real estate expensive and to support speculation over life and business itself. This one factor makes all Australians expensive no matter what they do.

Australian government policy has created this

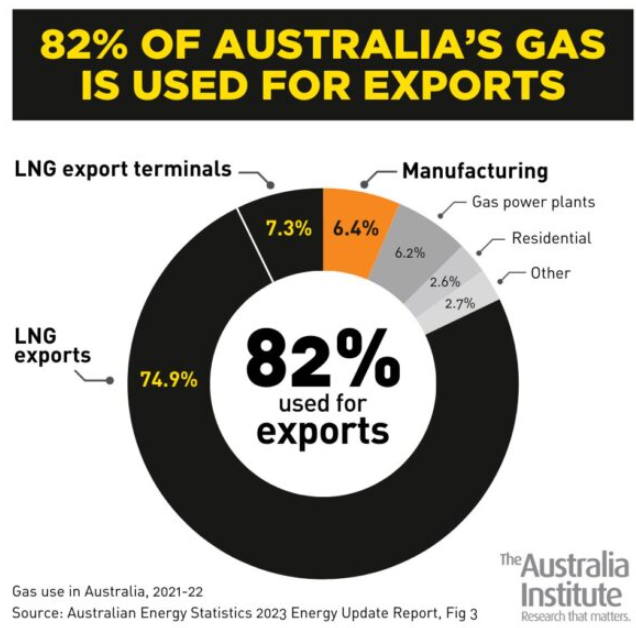

- Energy costs, and why a nation with a natural energy advantage is facing some of the highest consumer energy costs in the world, and businesses stating energy costs are a major factor in their viability?

How a nation with better energy resources than almost anywhere has given itself some of the world’s highest public electricity costs is an abysmal failure of public policy. It affects every Australian household and business and makes every Australian expensive no matter what they are doing with it.

That we do this to ourselves while enabling large multinationals to export our gas and coal while avoiding taxes is a generation’s worth of political cowardice. Even if we are making the green transition to non-carbon energy, we should have the world’s cheapest energy every step of the way.

Australian government policy has created this

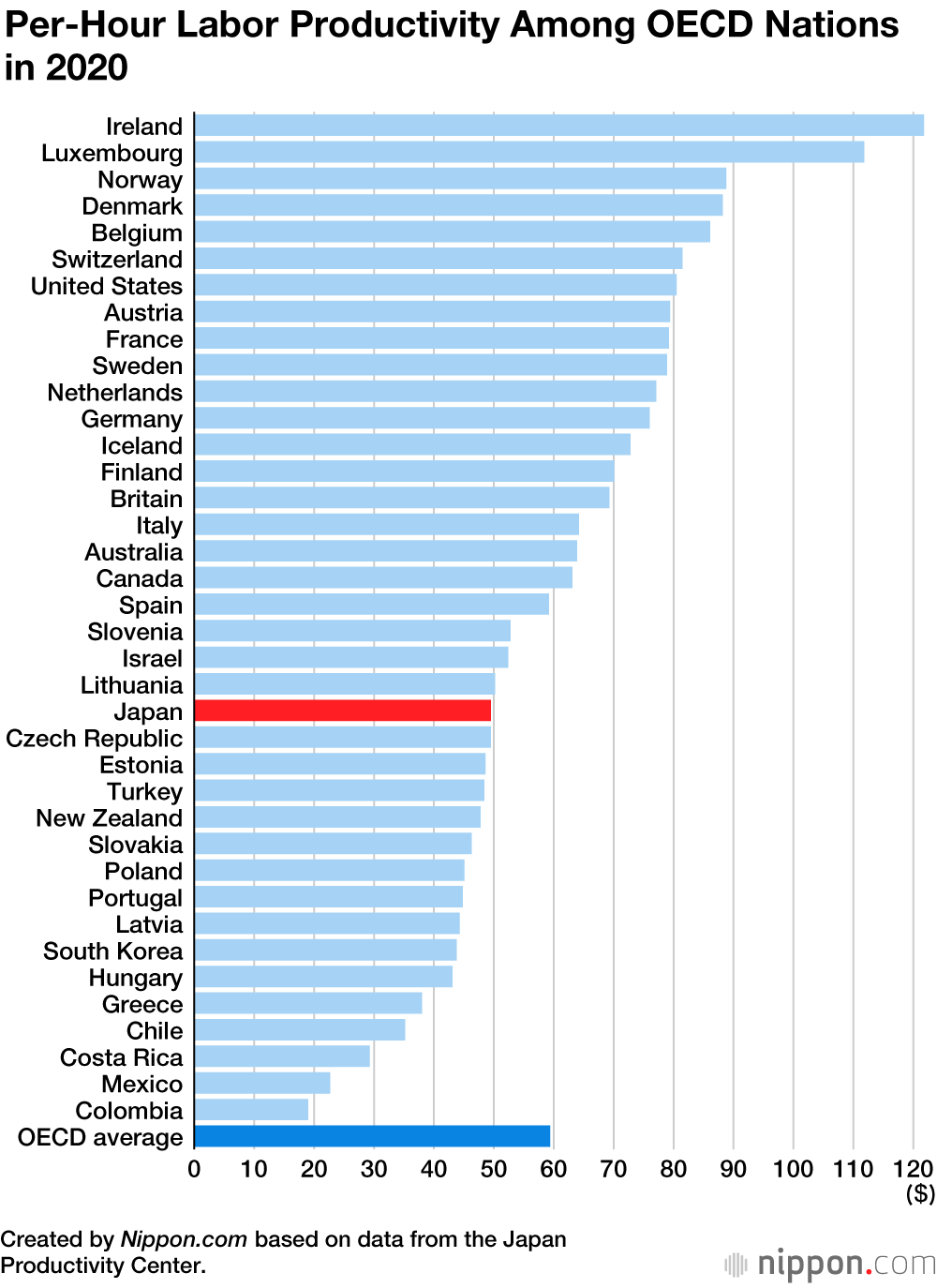

- Labour costs, both in Australia between market and non-market sectors of the economy, between sectors, between city and regional locations, and internationally compared?

Australian labour is expensive because Australians need to have a roof over their heads and pay energy bills. At the same time, government policy over more than a generation has been to create meaningless service sector employment in both market and non-market sectors while seeing past generations of investment in manufacturing walk away from the country.

The currency all Australians are paid in has been higher than it would otherwise be for a generation while commodity exports surged. Now that the end is near for much of that (the iron ore, gas, and coal for starters), the dollar pressures are coming from inflation, which is largely baked in by policy.

And while Australian labour is expensive, large numbers of Australians haven’t had a decent pay increase in ages, and global comparisons still show Australian workers deliver a strong bang for their buck.

- Infrastructure costs, social services, healthcare, and education costs and outcomes

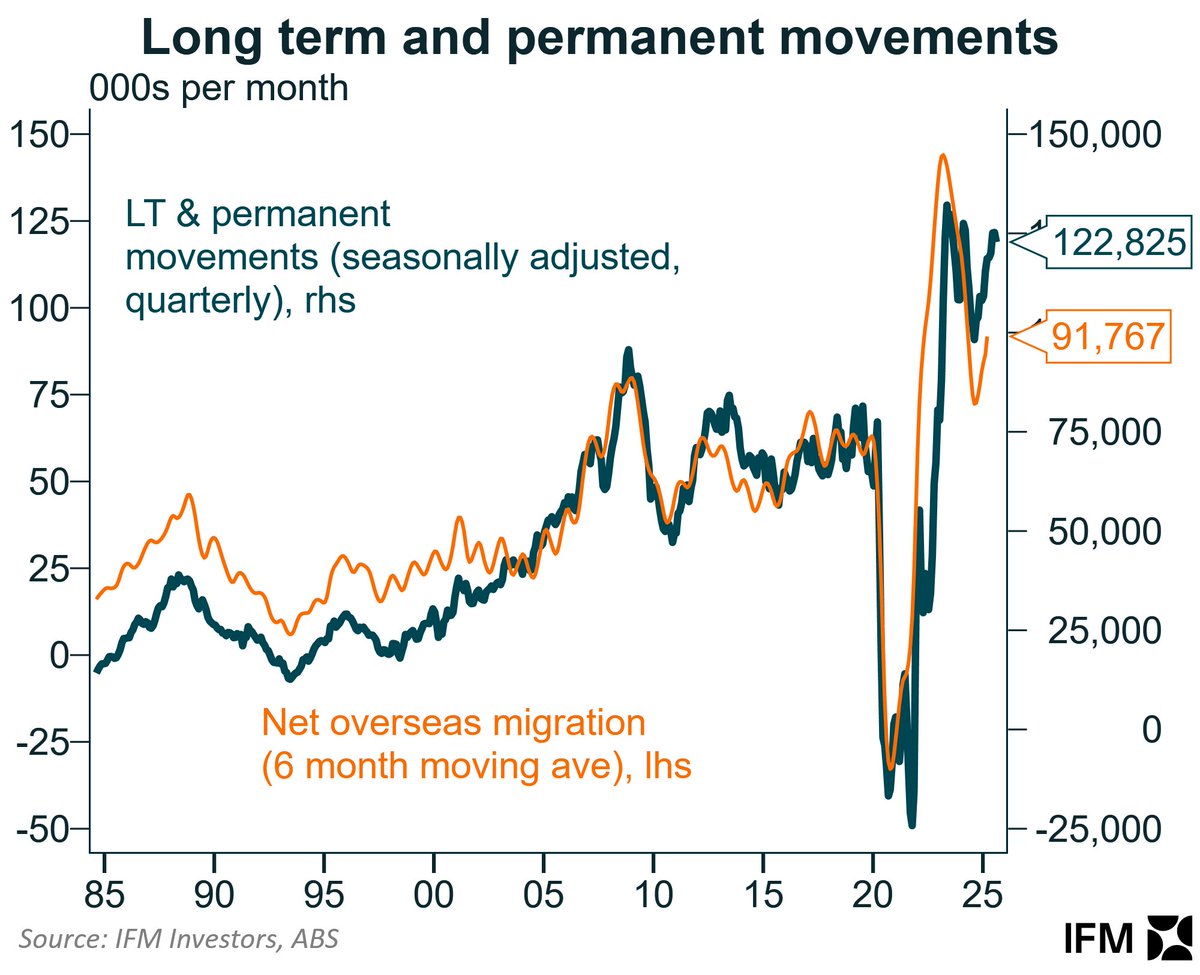

Before Australians get to work, they need to travel on crowded roads or public transport on roads or bridges or tunnels that have been expensively built to cater for population increase, which wasn’t planned or explained to Australia and is questionable for a nation offshoring its own external-facing economic sectors.

Then there’s the education for their kids and the infrastructure build mandated by the same immigration inflows. Then there’s the healthcare and social services required by Australians, now joined by hundreds of thousands of new people each year. This is baking in inflation too, which will pressure interest rates higher and pressure the AUD with it, making Australians more expensive.

- Immigration and what Australia’s immigration volumes imply and why it is needed.

Australia has the highest number of people born elsewhere in the OECD, and one-third of us were born elsewhere. At many levels beyond looking at whether they share our values or not, the question which needs to be asked is ‘why?’

Do we have an actual economic use to employ these people, which will enable Australia to achieve a better economic future, or are we simply bringing more people in to buttress the margins of those selling groceries energy housing and consumables to them, while creating meaningless government funded employment for them which means we are selling them and ourselves a pup by bringing them here.

Australian government policy has created this

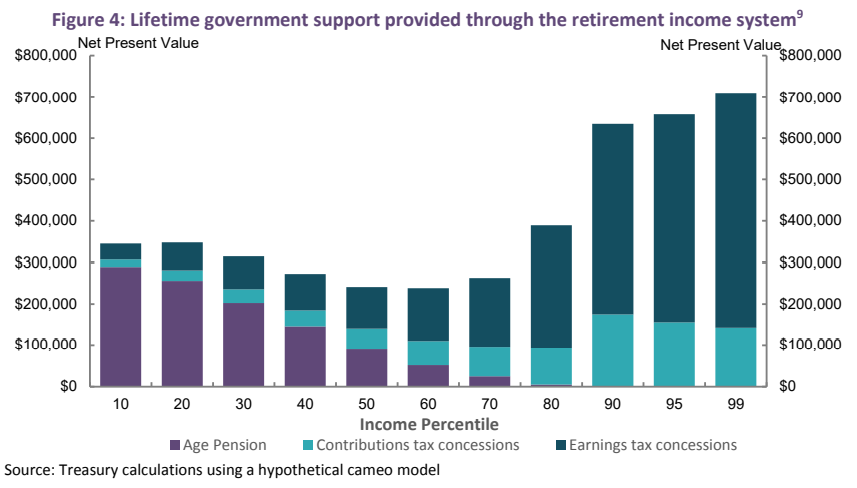

- Who pays tax in Australia, who gets tax offsets, and who receives direct outlays?

Okay, we get that we all pay tax and that richer people pay more tax than the rest of us. For the most part we agree we need to provide social services and build things for Australia’s future and ensure we have a capable defence. But between those points, who gets the offsets, who gets the government-funded contracts—and why?

Why aren’t Australian taxation payments and government outlays available for the public to see in real time? What are the effects of trusts and self-managed super funds as a means of avoiding taxation, who is using these, and what are the costs to Australians?

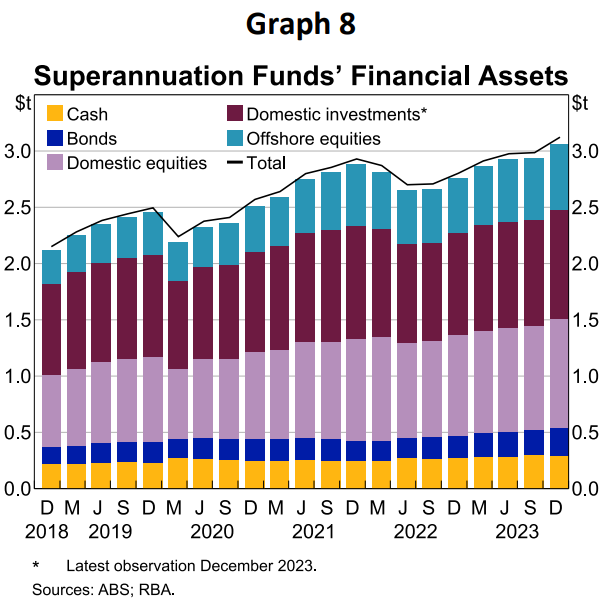

- Does superannuation work as intended to support Australians in retirement, and can it be expected to continue to do so for future Australians?

Superannuation was originally intended to relieve the pressure on the central budget for providing pensions for Australians after their working life. Any given advertisement for superannuation is likely to tout remaining with access to the publicly funded pension as a core desirable outcome.

Forty years after it was first introduced, super has become a game of tax avoidance and deferred contributions or benefits to enable intergenerational bequests, which serve primarily the affluent, while the person on the street wonders about life after their super accumulation runs out.

Then there’s the question of where the actual investment side of super goes. Does it go into a viable economic endeavour that will continue to generate an income for future Australians, or is it simply another shuffleboard game of pieces of paper swapping hands expensively from which players will walk away the moment the heat is on?

Australian government policy has created this and the benefits dont go to people on the street

- What sectors of the Australian economy have any scope for being internationally competitive? Can Australia expect the commodity exporting sector of the economy to continue to provide significant revenues?

Commodity crashes are certainly a thing of Australia’s past, and as a nation spectacularly reliant on commodities now, we can expect them into the future. The only protection from them is having another economic sector that does something the country uses.

In 2026 just about everything we use at home or in the office or at any point between them is imported; the online systems we use to buy, diagnose, seek advice, or even meet people with are all from somewhere other than Australia.

If we can’t bring ourselves to do something efficiently, then why, again, are we importing as many people as we do?

- Does Australian education represent good value for money for Australians? Does it provide them with cost-effective skills utilised in careers accessible by them, or is it accrediting them for workplaces not using their skills?

Anyone with kids will tell you education has become very expensive, but what are our education systems providing for future Australia?

At a tertiary education level we sell to people offshore some of the most expensive educations on the planet, when for the most part the people taking up these opportunities choose Australia because we encourage them to live here.

At one level this is great—well-educated neighbours from somewhere else are often interesting. But are we creating a layer of uber-educated Uber drivers or fast food workers or administrative nuff-nuffs?

Why is it that we don’t churn out enough nurses and medical professionals and large numbers of people chalk up ‘business’ qualifications, which are often meaningless and they are likely to never use

One of the reasons economic and budget reform is a politically difficult and risky path is that it simply isn’t possible to address one of the issues above without the other issues above becoming factors. That means it is a whole box and dice approach.

But a generation’s worth of putting in the small economic reform steps means that the whole box and dice is now needed.