Exclusively from national treasure, Gerard Minack.

Australian rates and sticky inflation

Expectations for RBA policy have swung 180° through the past three months, from easing to tightening, as inflation lifted through the second half of 2025. There is noise in the data so I’m not as sure as the market that the RBA will tighten at this week’s Board meeting. But underlying inflation is sticky, in part because weak productivity implies that current wage growth is too high, and in part because high migration is pressuring housing costs (construction of new homes and rents).

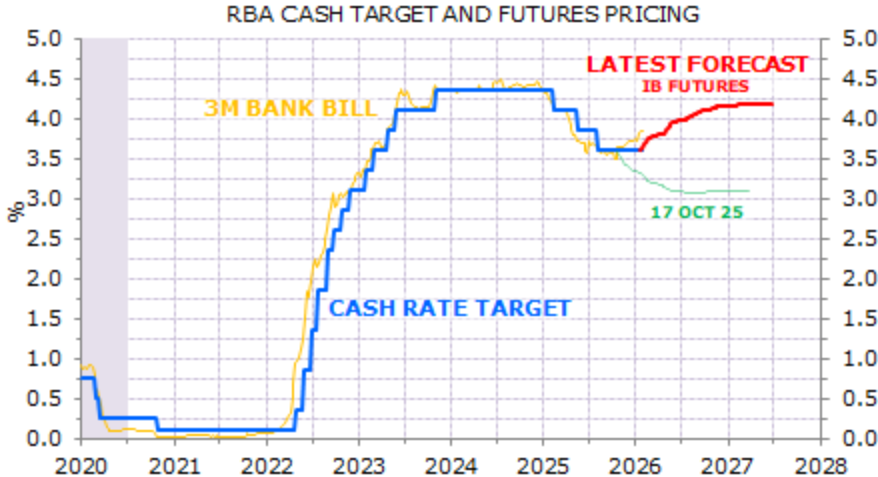

Australian inflation rose through 2025. The trimmed mean increased by 2.9% at an annual rate in the first half, and 3.7% in the second; headline CPI increased from 3.0% to 4.5%. Rate markets have swung from pricing rate cuts to now expecting a couple of 25bp increases (Exhibit 1).

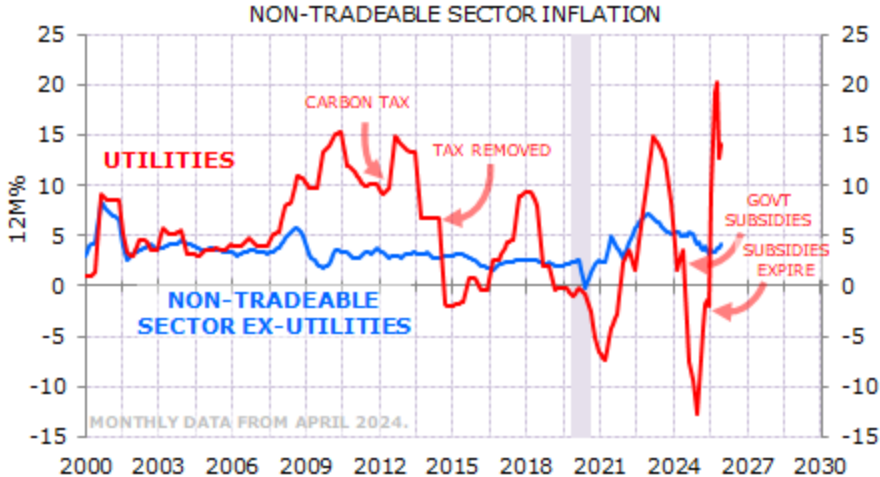

There is noise in the data. Federal and State government subsidies have affected housing and utility prices (Exhibit 2). Moreover, the ABS is still bedding down the new monthly CPI series.

Markets expect the RBA to tighten this week. I’m not as sure: the (relatively new) RBA policy board may be reluctant to tighten so soon after the last rate cut (August) and could decide to wait for the March quarter CPI before adjusting policy.

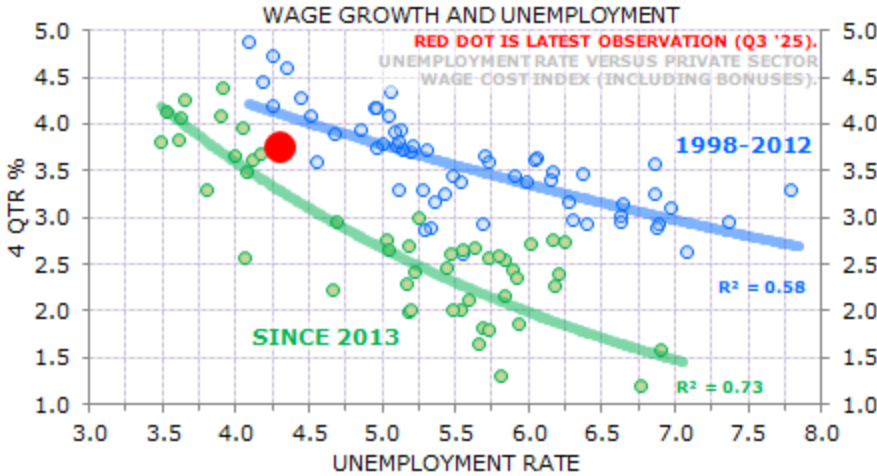

However, the RBA will need to reconsider some of its key assumptions. First, the relationship between unemployment and wage growth. From 2013 wage growth was persistently lower for any given unemployment rate than it had been in the prior 15 years (Exhibit 3). If that post-2013 relationship persists then an unemployment rate around 4% would lead to wage growth of around 3½% – a pace the RBA had seen as consistent with its 2-3% inflation target. If the pre-2013 relationship has returned, then the current unemployment rate, 4.1%, would not be compatible with target inflation.

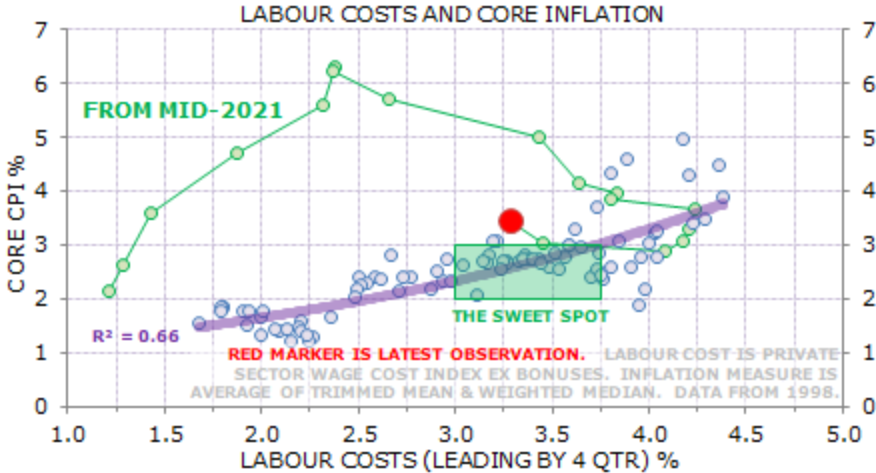

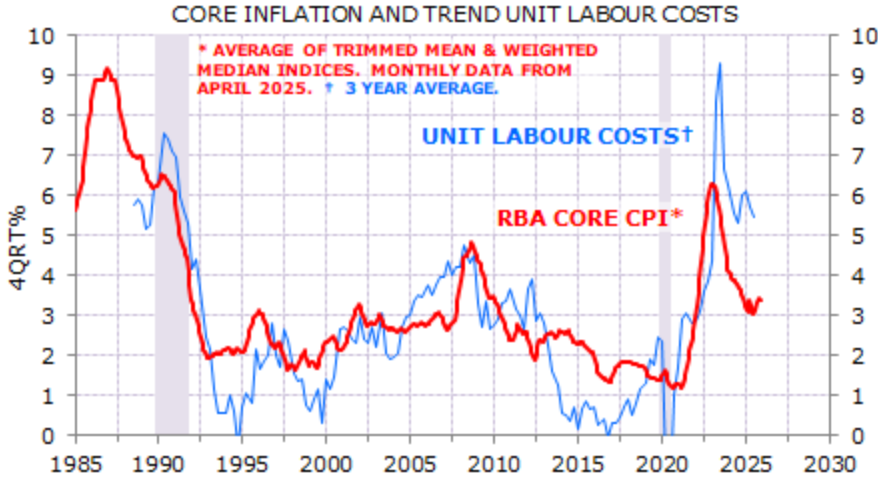

The second assumption is what level of wage growth is compatible with the Bank’s inflation target. Historically the Bank seemed to believe that the sweet spot for wages was 3-3½% or 3¾%. Private sector wage growth is in that range (as measured by the Wage Price Index) yet inflation is not in the Bank’s target range (Exhibit 4).

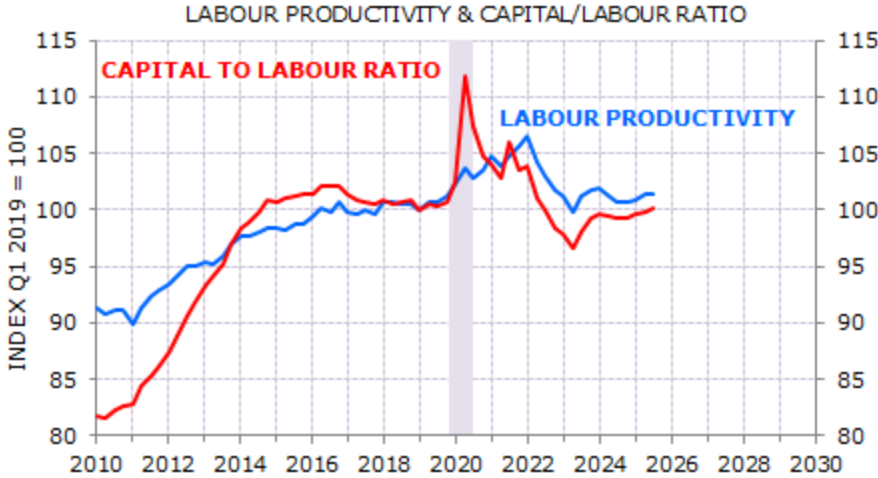

The problem is the wage growth consistent with target inflation depends on labour productivity growth. Australia’s productivity growth has stagnated over the past decade (Exhibit 5).

Unit labour costs – wages adjusted for productivity growth – are volatile. But trend unit labour costs (a 3 year average) are rising too fast to be consistent with a return to target inflation (Exhibit 6).

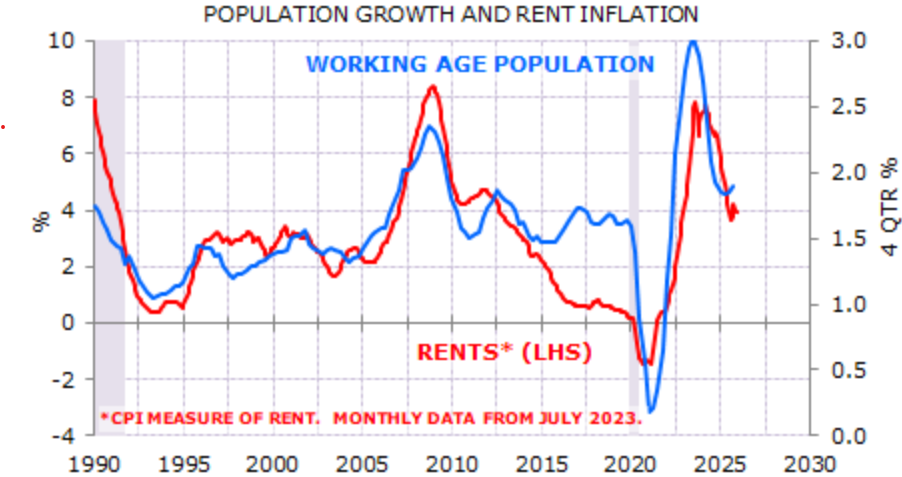

Is Government policy contributing to inflation? Every galah in the national financial press menagerie is squawking about how high government spending adds to inflation. They’ve got it wrong. The government policy that is contributing to high inflation is fast migration-led population growth. Housing construction and rents are the two largest items in the CPI. Both contributed to the second half rise in inflation. Both are driven in part by population growth (Exhibit 7).

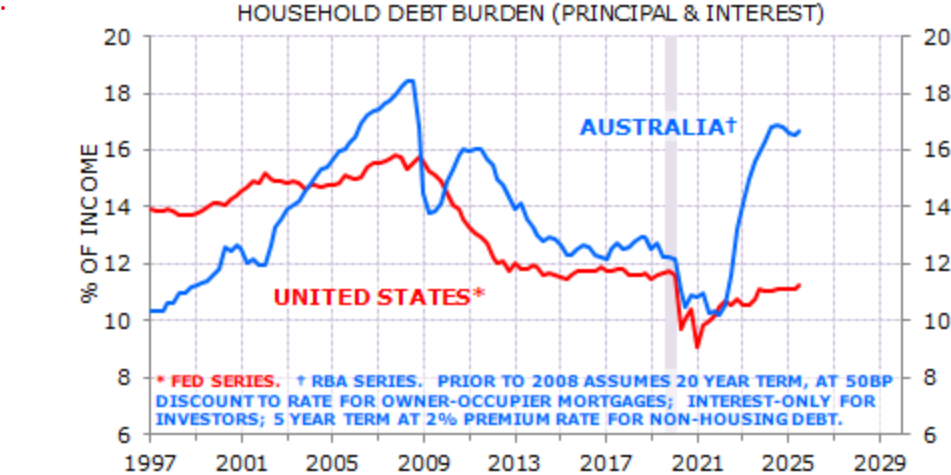

Like the RBA, I was wrong-footed by the pick-up in inflation through 2025. I should have put more weight on the implications of poor productivity and fast population growth for inflation. In hindsight, the RBA did prematurely ease policy last year. However, I still think policy is restrictive. RBA tightening has, for example, had a much larger impact on household finances than Fed tightening (Exhibit 8). If the Bank does reverse course and tighten – if not this week, then in May – then it seems likely that Australian growth will start to decelerate through the second half.

Chart 7 is the money shot.