Will Hamilton, the CEO and founder of Hamilton Wealth Partners, is the latest commentator to warn of dire impacts on Australia’s rental market if the federal government reduces the capital gains tax (CGT) discount or limits negative gearing.

It is worth critiquing Hamilton’s main arguments as they pertain to the rental market.

First, Hamilton argues that the temporary abolition of negative gearing by the Hawke/Keating government between 1985 and 1987 drove up rents across the capital cities:

“Changes to CGT, possibly combined with a removal of negative gearing, will have an adverse effect on the rental market”.

“Keating removed negative gearing between 1985 and 1987, and it was seen as a significant factor in increasing rental levels across capital cities and was subsequently unwound”.

I thoroughly debunked this myth in 2019, showing that real inflation-adjusted rents rose sharply before and after the change to negative gearing:

According to the ABS’ rent data, real inflation-adjusted rental growth only rose in Sydney and Perth (where vacancy rates were already low), whereas real rental growth was flat or fell elsewhere.

There was also no discernible impact nationally, with rental growth much higher both before and after the change (the period where negative gearing was abolished is shown in red above).

My view was supported by separate analysis from independent economist Saul Eslake, who stated the following in a speech to Prosper Australia:

“If the abolition of ‘negative gearing’ had led to a ‘landlord’s strike’, as proponents of ‘negative gearing’ repeatedly assert, then rents should have risen everywhere (since ‘negative gearing’ had been available everywhere)”.

“In fact, rents (as measured in the consumer price index) only rose rapidly (at double-digit rates) in Sydney and Perth—and that was because in those two cities, rental vacancy rates were unusually low (in Sydney’s case, barely above 1%) before negative gearing was abolished”.

“In other State capitals (where vacancy rates were higher), growth in rentals was either unchanged or, in Melbourne, actually slowed”:

The Grattan Institute also supported my finding:

“Although the tax changes were nation-wide, inflation-adjusted rents were stable in Melbourne and actually fell in Adelaide and Brisbane”.

“In Sydney and Perth, rent rises were in fact driven not by tax changes but by population growth and insufficient residential construction – due to high borrowing rates and competition from the stock market for funds”.

ABC fact Check also supported my finding:

“Over the period when negative gearing was abolished only Sydney and Perth experienced strong growth in real rental prices”.

“Real rents in Adelaide and Brisbane fell considerably over the period, whilst Melbourne experienced low, or at times no, real growth in rents”.

Next, Hamilton argues that Victoria’s onerous taxes on investors have driven down rental supply and pushed up rents:

“Simply look at the onerous levels of land tax in Victoria that was designed to increase the housing supply for home buyers, but which, combined with regulatory changes on landlords, has led to a landlord exodus—in turn, reducing rental supply and driving up rents”, Hamilton wrote.

Hamilton fails to acknowledge that when an investor sells, the property does not vanish. Instead, it will either be purchased by another investor or an owner-occupier (possibly a first home buyer).

Accordingly, the balance between rental supply and demand does not change. Instead, there will be fewer investors and more owner-occupiers. There will be fewer homes available for rent, but fewer people will need to rent.

In fact, Victoria provides the perfect counterpoint to Hamilton’s argument.

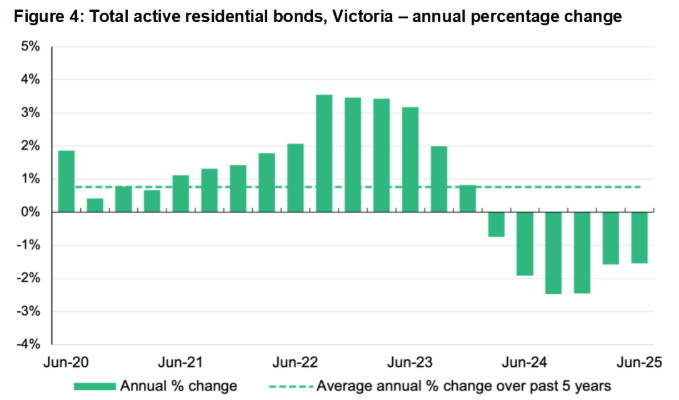

It is true that a substantial number of investors have exited the market, as demonstrated by the decline in rental bonds on issue:

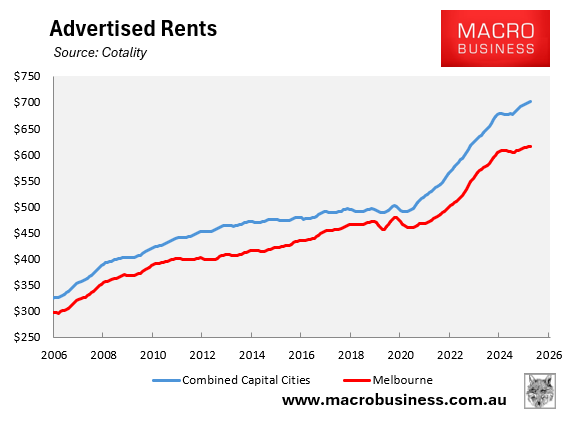

However, the reduction of investors has not resulted in higher Melbourne rents or reduced affordability relative to the rest of the nation.

According to Cotality, Melbourne advertised rents increased by 36% in the five years to January 2026, significantly less than the 43% increase observed across the combined capital cities.

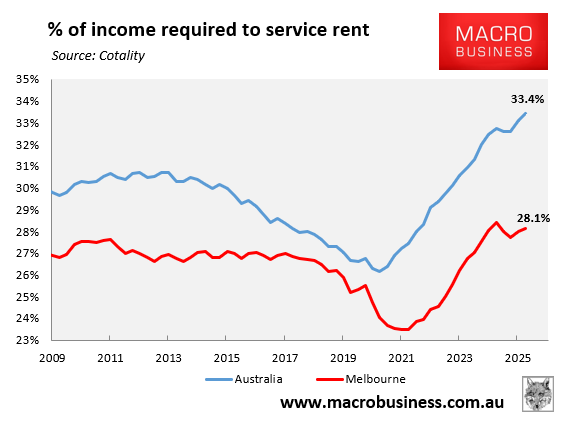

In Q3 2025, the share of income necessary to rent the median home in Melbourne was 28.1%, which was significantly lower than the national average of 33.4%.

Therefore, Cotality’s data shows that Melbourne’s rental affordability is significantly better than the national average, despite the flight of property investors caused by the government’s tax reforms.

Melbourne demonstrates why adjustments to the CGT discount or negative gearing are unlikely to harm the nation’s rental markets.

While there will undoubtedly be fewer investors in the market, the loss of rental stock will be countered by an increase in first-time buyers and a decrease in renters seeking housing.

There is no reason for renters to be concerned about changes to the property tax concessions.

First home buyers looking to purchase will also face less competition from investors.