International students ruthlessly exploit Australia’s visa system

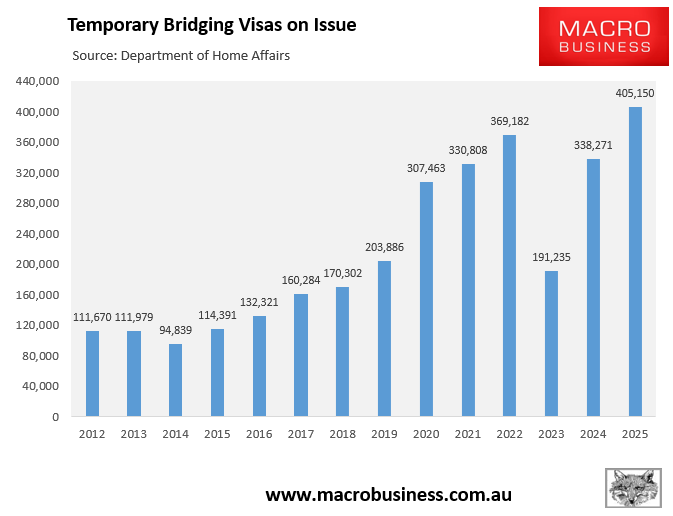

I reported earlier in the week on the massive rise in bridging visas, which has been driven by former international students.

As illustrated above, the number of bridging visas on issue ballooned by 201,300 between Q3 2019 and Q3 2025.

The Attorney-General’s department recently reported an “unprecedented surge” in appeals over student visa refusals, which is partly behind the blowout of bridging visas.

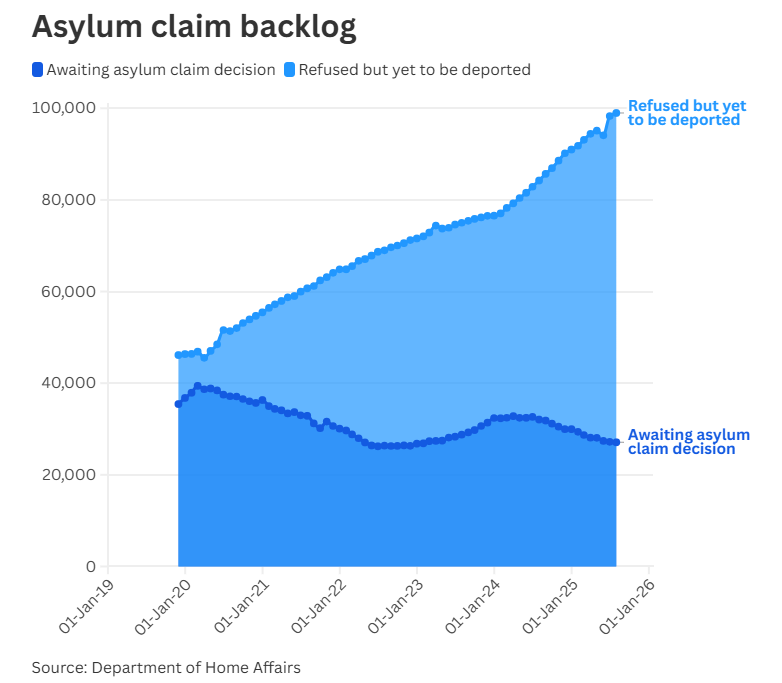

Frank Chung of News.com.au also reported on the dramatic increase in migrants attempting to claim asylum.

Former senior immigration department bureaucrat Abul Rizvi told Chung that “there’s an increasing number of student visa holders applying for asylum”, and that it risks creating a “massive underclass” that could negatively impact “social cohesion”.

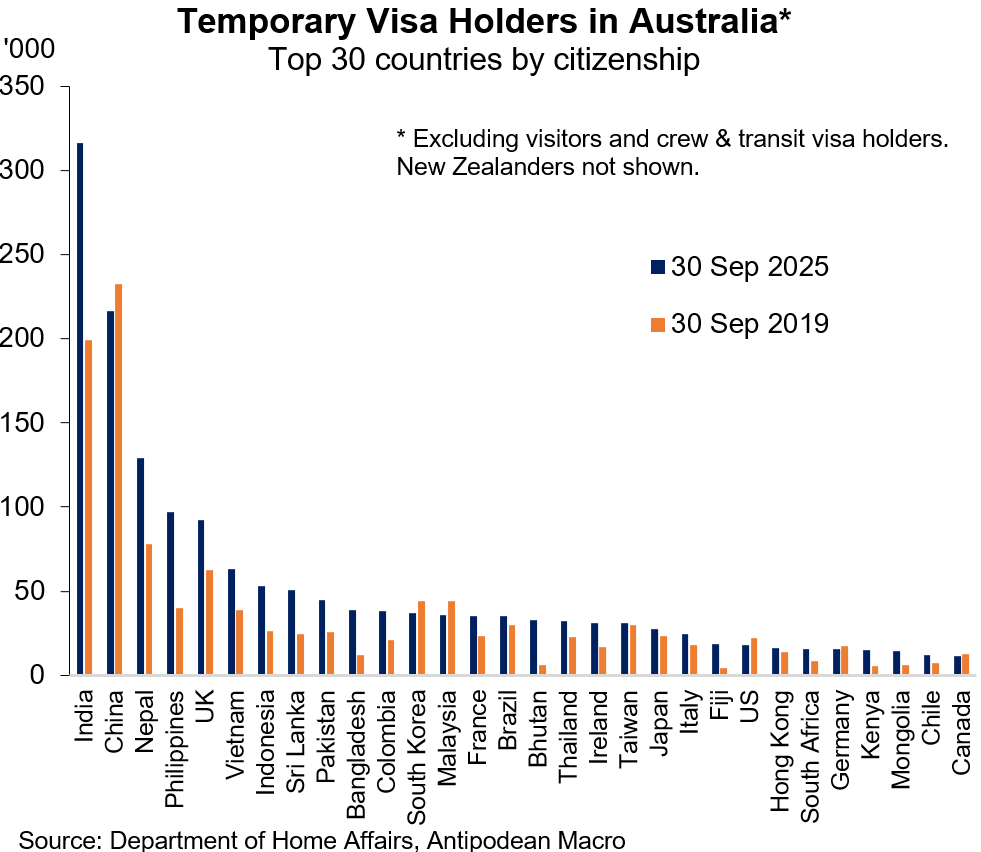

Indians have driven the surge in temporary migration and bridging visas in Australia.

Data presented below by Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro showed that, excluding New Zealand citizens, “Indian citizens in Australia held the most temporary visas by far, followed by Chinese citizens (who were #1 six years prior)”:

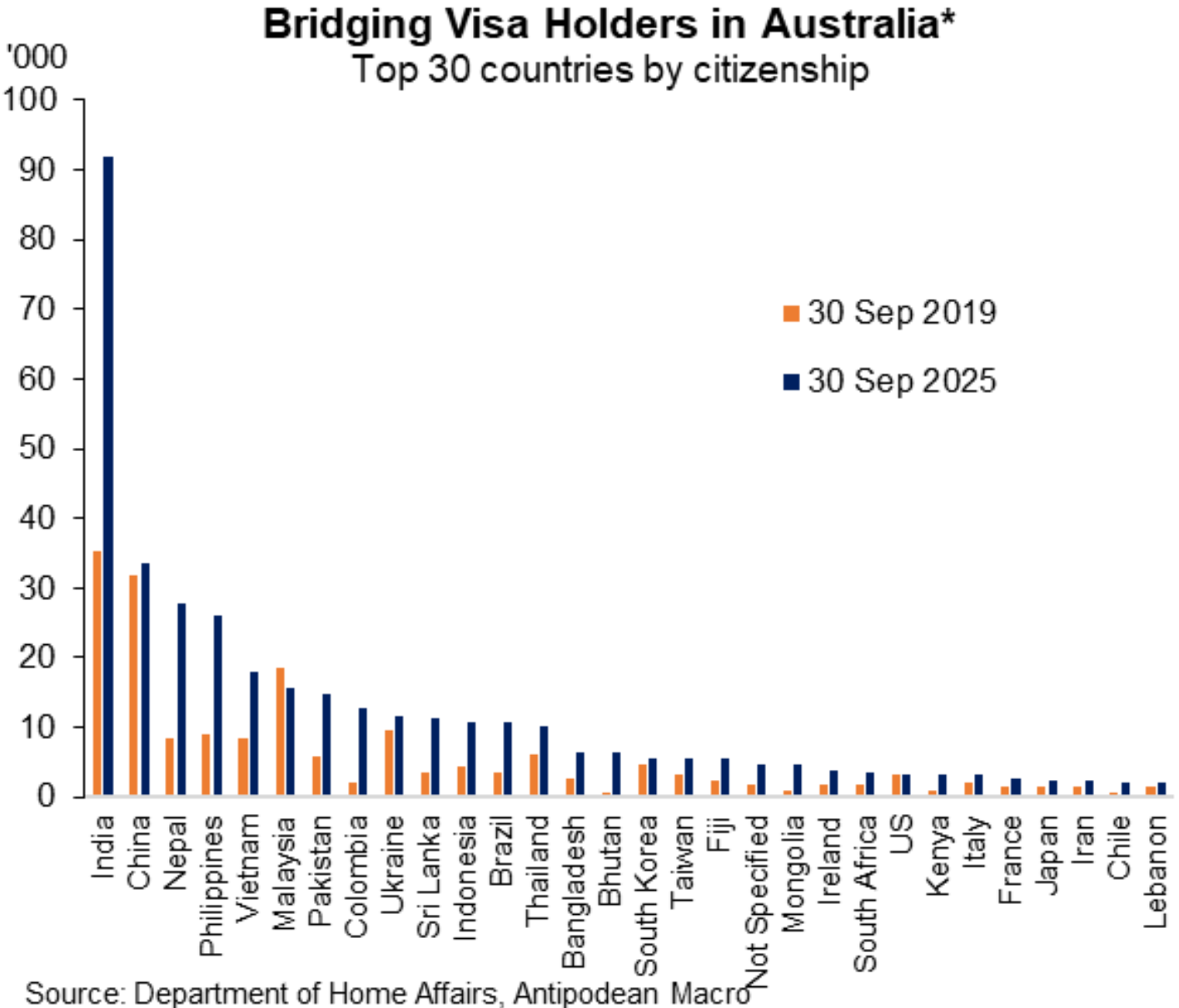

Indians have also driven the growth in bridging visas, dwarfing every other source country:

Salvatore Babones, associate professor at the University of Sydney, published a newsletter meticulously outlining how “non genuine” international students, especially from India and Nepal, are using university enrolments as a pathway to work rights and residency, rather than study.

Babones explains how tens of thousands of people enter Australia on student visas with no intention of completing a degree. Instead, they use loopholes in the visa system to gain multi‑year, unrestricted work rights at very low cost.

Universities—especially those with Sydney satellite campuses—are knowingly enabling this behaviour, and that government inaction has allowed the problem to explode.

Babones explains the scam as follows.

First, enroll at a public university and then drop out immediately.

Public universities have high visa approval rates, so they’re the easiest entry point. At 11 universities, more than 30% of first‑year international undergraduates drop out. Central Queensland University tops the list with a 57.2% dropout rate.

Second, switch to a cheap private college (a practice called “course-hopping”).

After dropping out, students apply for low‑cost hospitality or cooking courses. While waiting for approval, they receive a bridging visa with full work rights. The median wait for approval is 28 weeks.

If refused, they appeal to the Administrative Review Tribunal (ART). Babones notes that there are 42,098 course‑hopping cases, constituting more than one-third of the ART’s total caseload pending, with a median wait time of 64 weeks. Again, full work rights are available while they wait.

Third, even after refusal, apply for asylum.

Asylum applications are almost always rejected, but they create another multi‑year delay. Appeals back to the ART extend work rights even further.

“This is all legal”, Babones explains. “But it only happens because Australia gives essentially unlimited work rights to international students”.

“During the teaching semester, international student hours are technically limited, but those limits are not enforced. When a student drop-out is on a bridging visa, there are no limits at all”.

“From the non-genuine student’s point of view, the long waits on bridging visas are not a deterrent. They are a desirable feature of the system”, Babones argues.

The scale of the problem is massive.

As of mid‑2025, 107,274 former students were on bridging visas—up from 13,034 in 2023. That’s over 10% of all international students.

The total cost to obtain 2-plus years of work rights is under $25,000 (i.e., one semester tuition + fees).

Babones notes that many regional universities have opened Sydney city campuses to attract these students.

About half of these campuses are run by for‑profit contractors. Universities profit even when students never attend classes.

“As with so many other aspects of Australia’s temporary migration system, it’s all a rort”, Babones argues. “It’s a profitable rort for universities—and for the companies that exploit this large pool of insecure, unskilled labour”.

Babones recommends a single, strict rule to counter the rorting by non-genuine students:

“Require students who drop out of their initial programs to return home and reapply from offshore for any future study”.

This would end course‑hopping, remove incentives for gaming the system, and be simple and automatic to enforce.

More broadly, Australia must choose between having a genuine international education system, or a de facto low‑cost migrant labour program.

“International study should not be a low-cost labour program”, Babones says. “If Australia wants access to a large pool of immigrant labour to staff its convenience stores, deliver its food, and keep wages down, it should put in place a formal guest worker program”.

“Personally, I’d rather live in a high-wage country that relies on mechanisation and self-service to meet its needs”, Babones argues.

I couldn’t agree with Salvator Babones more.