Australia faces energy Hunger Games

Despite being the world’s largest coal exporter and the second-largest natural gas exporter, Australia is facing an energy-scarce future.

Under the Albanese government’s 82% renewable energy target (RET), most of Australia’s existing coal fleet is required to close, to be replaced by roughly 6–7 GW of new large‑scale renewable generation per year (plus several gigawatts of storage).

However, Australia’s transition to large‑scale renewable energy stalled sharply in 2025, with investment in utility‑scale solar and wind falling to less than half the previous year’s level.

Large‑scale solar and wind investment fell to 2.1GW, down from 4.3GW in 2024, and around one-third of the 6–7 GW per year required to stay on track for 2030.

It was the third‑worst year in a decade for final investment decisions.

Even with the federal Capacity Investment Scheme (CIS) aiming to fast‑track 40GW by 2030, 12.5GW of the 13GW awarded had not yet reached financial close by late 2025.

Utility‑scale solar investment fell to $961 million, less than half the previous year. Solar installations are forecast to drop 21% in 2026, pressured by:

- development delays;

- competition from rooftop solar’, and

- falling wholesale solar prices.

“Investment in large-scale renewables has been sporadic in Australia, reflecting shifts in federal and state policies that support clean energy”, BNEF head of Australia research Leonard Quong said.

“Despite government support for renewable energy projects being at an all-time high, BNEF does not expect investment to return to the peaks seen in 2018 or 2022”.

The sluggish rollout of renewables makes sense. After all, why invest in more intermittent wind and solar capacity when you compete with the existing glut of supply (reflected in low spot prices) and risk having your returns crimped by future projects?

This sluggish rollout of renewables also contributed to Origin Energy extending the life of the Eraring coal plant—Australia’s largest—by two years to maintain system reliability.

At the same time as the supply of generation has stalled, demand continues to rise.

First, dozens of new data‑centre builds and expansions are in the pipeline across Australia, driven by AI, cloud demand, and hyperscale investment.

“Should all the planned and proposed Data Centres be completed, they will add an additional 1.7 Gigawatts of power capacity across Australia by 2029”, noted a September 2024 report from M3 Property.

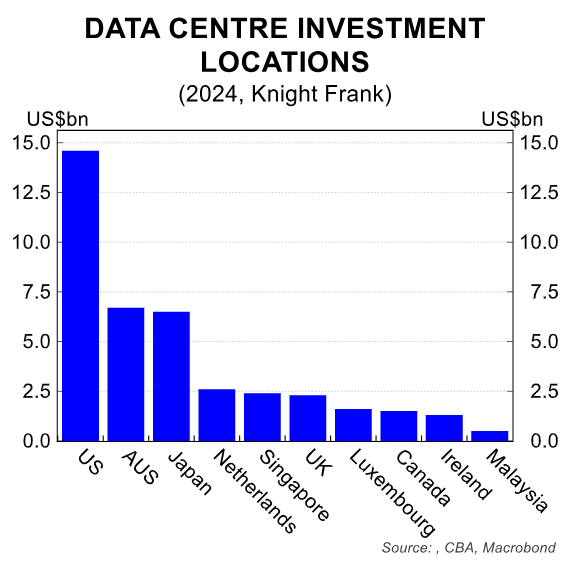

Australia ranks among one of the world’s top data centre hubs, with over 250 facilities. A recent report by Knight Frank indicates in 2024, total data centre investment equated to around $US6.7 billion, the second highest level of any nation, behind the U.S.

Sydney holds 56% of Australia’s $30 billion data‑centre market, indicating the largest share of ongoing and planned projects. Melbourne holds 30% of the national market and is emerging as a major regional hub.

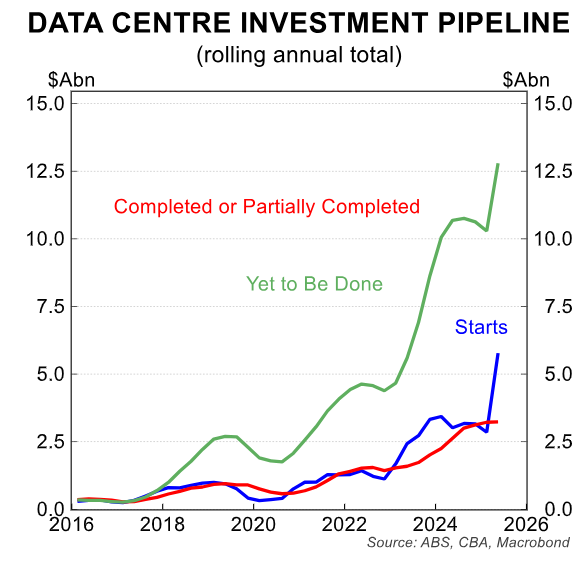

As illustrated below by CBA, the data centre investment pipeline has swelled:

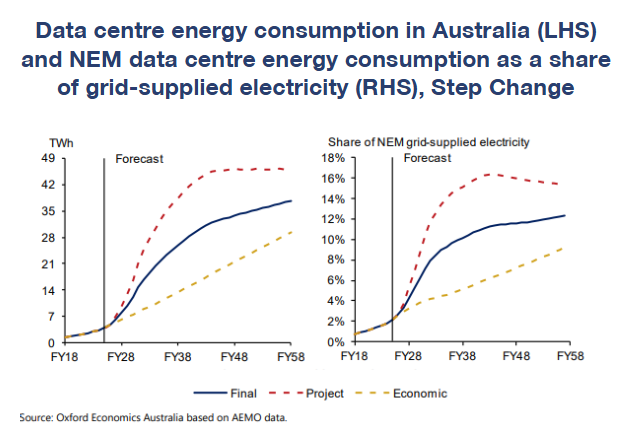

CBA summarises the energy implications as follows:

“In 2024-25, Australian data centres are estimated to have consumed 4TWh of electricity, equating to 2.2% of total NEM consumption. This is forecast to grow to 12TWh by 2029-30 and reach 34TWh by 2049-50, representing up to 12% of grid supplied electricity (chart 11)”:

“In addition, data centres consume decent amounts of water. In Sydney and Melbourne, data centres account for 0.7% and 0.2% of yearly local water usage, respectively. As data centre capacity grows, nationwide data centre water usage is forecast to rise to 17GL by 2030”.

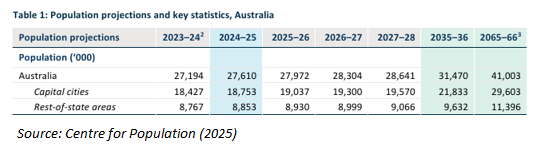

If the situation wasn’t bad enough, Australia’s population is also officially projected by the Centre for Population to balloon by 13.4 million over the next 41 years to 2065–66, equivalent to adding another Sydney, Melbourne, and Perth to the current population:

Adding 13.4 million people (nearly a 50% increase) to Australia’s population would obviously require a massive increase in the supply of energy generation, even without the added demand from data centres.

How do Australian policymakers realistically hope to close down baseload generation to achieve ‘net zero’ without causing massive energy scarcity and widespread economic and social carnage?

With massive planned population growth and the rapid expansion of data centres, achieving energy security and ‘net zero’ are impossible goals.