Australian dollar holds firm as US job losses mount

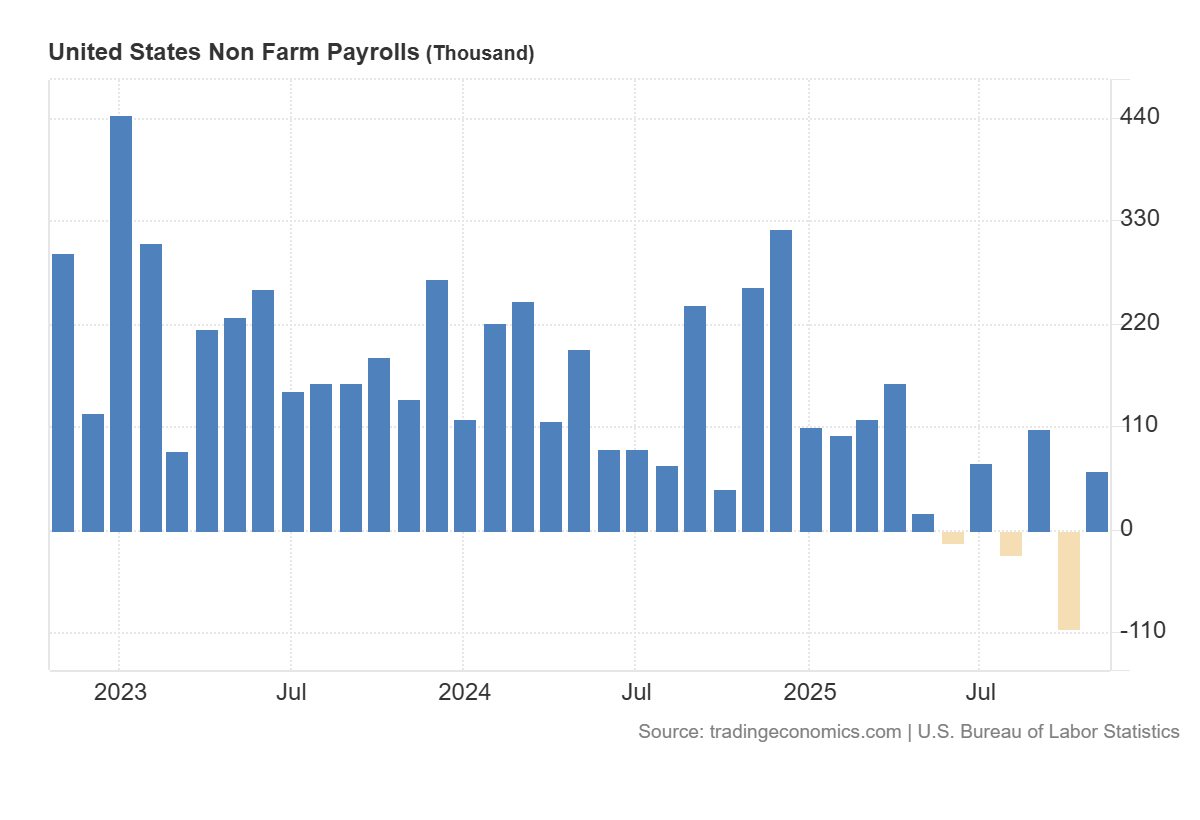

Overnight we saw the release of both the October and November US jobs reports which at first glance looked nominal but in reality show a worsening employment situations as jobs growth slows even as immigration goes into nearly reverse. A new 4 year high in the unemployment rate at 4.6% plus downward revisions on all previous releases that were missed/obfuscated/massaged by the Trump regime.

From the BLS:

US job growth totaled 64K in November, compared with a 105K loss in October and market expectations of a 50K increase. Employment rose in health care and construction in November, while federal government continued to lose jobs. In November, health care added 46K jobs and construction 28K jobs. Employment in social assistance continued to trend up as well (+18K). On the other hand, employment fell in transportation and warehousing (-18K). Also, federal government lost 6K jobs in November and 162K jobs in October reflecting the departure of federal workers who accepted deferred buyouts as part of Trump’s push to shrink the size of government.

So any thoughts of a hawkish stance by the Fed going into 2026 are fanciful at best as the potential for recession grows. This has seen the USD continue to fall against most of the majors with Euro, Pound Sterling, Yen and Canadian Loonie all making highs overnight against “King” dollar.

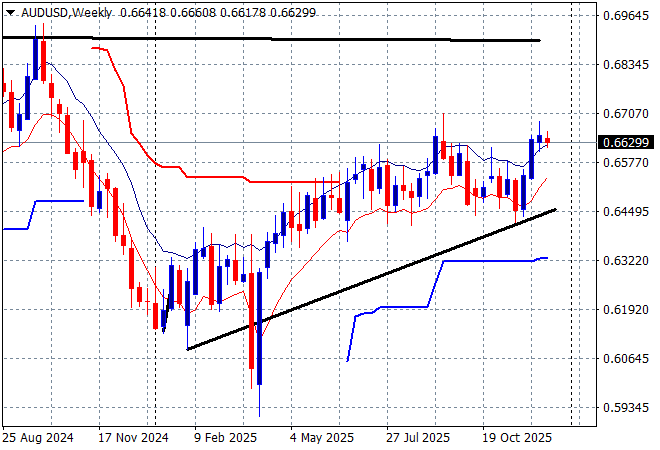

The standout however has been the Australian dollar which seems stalled around the 66 cent level after recently fighting back from its own lows as speculation mounts if the RBA will indeed become more hawkish in 2026.

There isn’t a broad consensus that the RBA will actually hike rates in 2026 with Westpac this morning releasing its views that a hold throughout the year is more likely:

The Australian economy has been playing out broadly as Westpac Economics expected.

Public sector demand growth is slowing and indeed was negative over the first half of 2025. Private sector demand growth is recovering, and the labour market is gradually easing. Underlying growth in labour costs is also easing, and productivity growth is already running faster than the RBA’s pessimistic trend assumption.

Our forecasts see 2026 as involving further recovery from the period of very weak private sector demand growth. The ‘shaky handover’ risk, of private sector growth not picking up as public sector demand growth normalised, looks to have dissipated.

Inflation saw a bump in September quarter and October month. The main sources of the surprise had little to do with domestic demand or labour market pressures. Rather, a sizeable part of that bump looks to have been administered prices and noise. The RBA recognised this at the time but has since communicated that it is more worried about upside risks to inflation.

And since what matters for monetary policy is how the RBA sees things, this means that rate cuts are off the table for the time being.

We expect inflation to get back to the RBA’s target (and below the midpoint of the 2–3% range on a trimmed mean basis), but not until later in 2026. This is too late to give the RBA enough comfort to start cutting rates on our previously expected timetable of May and August 2026.

Accordingly, we push out the earliest feasible timetable for rate cuts beyond 2026. If our inflation and labour market view is right, by the end of 2026 it will become apparent that domestic inflation pressures have eased. This would leave the way clear to remove remaining policy tightness in the first half of 2027 – we pencil in February and May 2027 for that normalisation.