Australia will never build enough homes

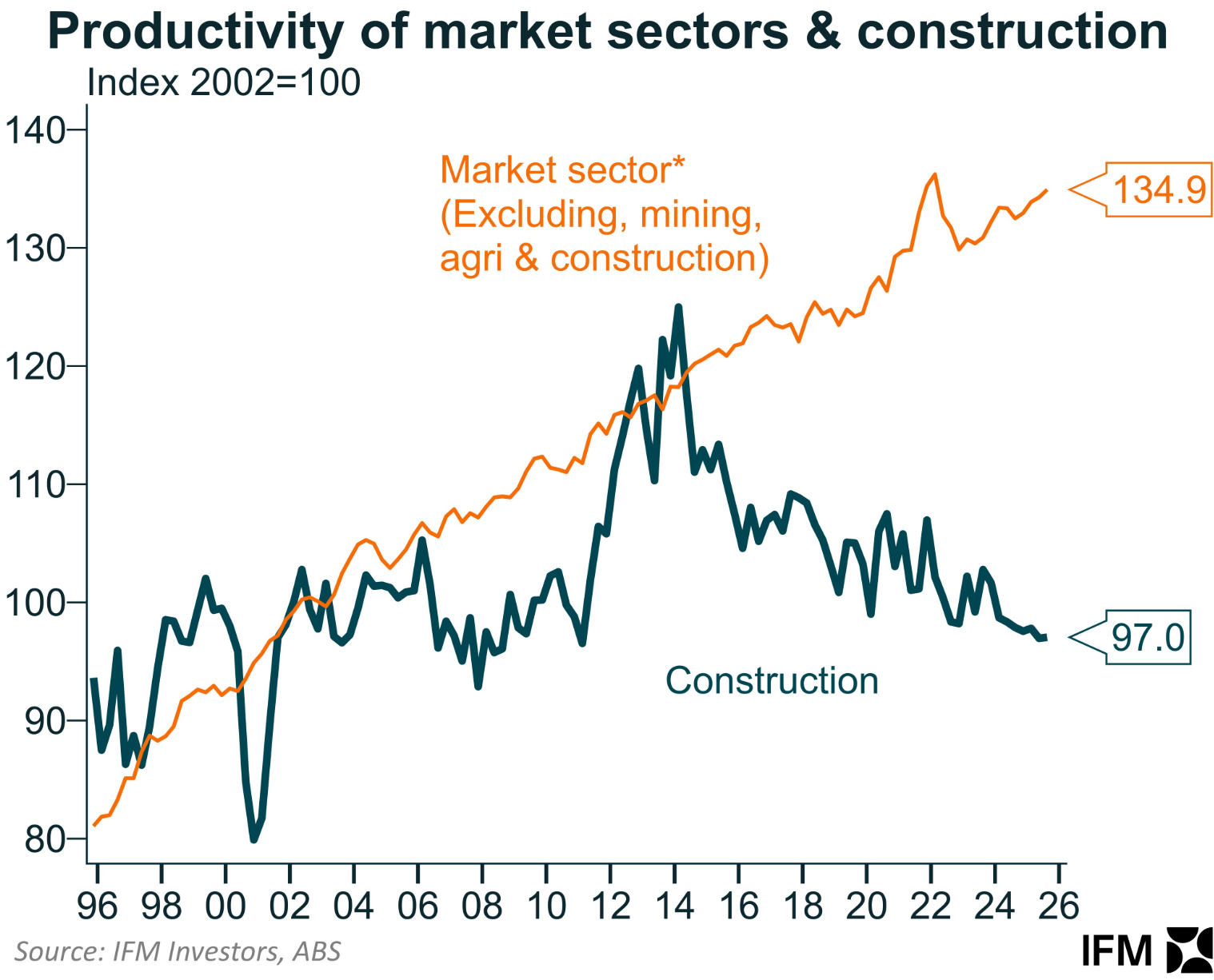

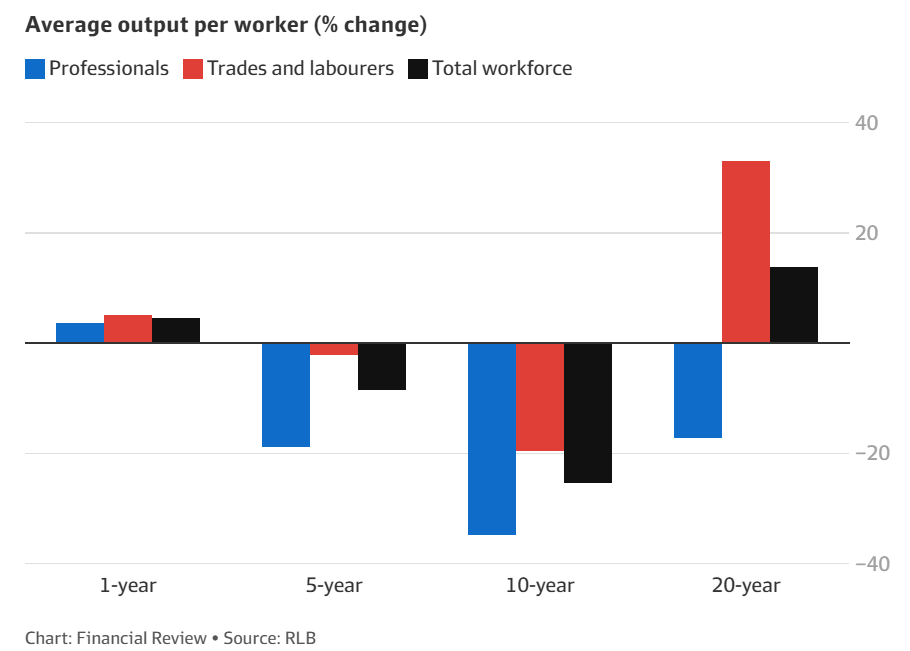

Alex Joiner, chief economist at IFM Investors, posted the following chart on Twitter (X) showing the long-run collapse in construction sector productivity:

“If we want to address supply issues in residential construction and deliver non-resi and infrastructure projects on time and budget, then we need to foster productivity growth in the construction sector”, Joiner said.

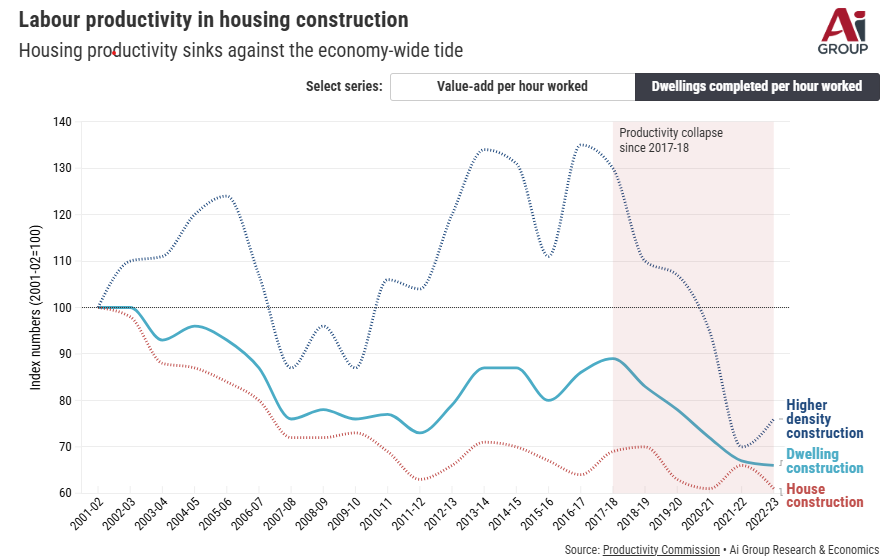

Reflecting the collapse in productivity, recent analysis from the Australian Industry Group showed that there has been a corresponding decline in the number of homes built per hour worked.

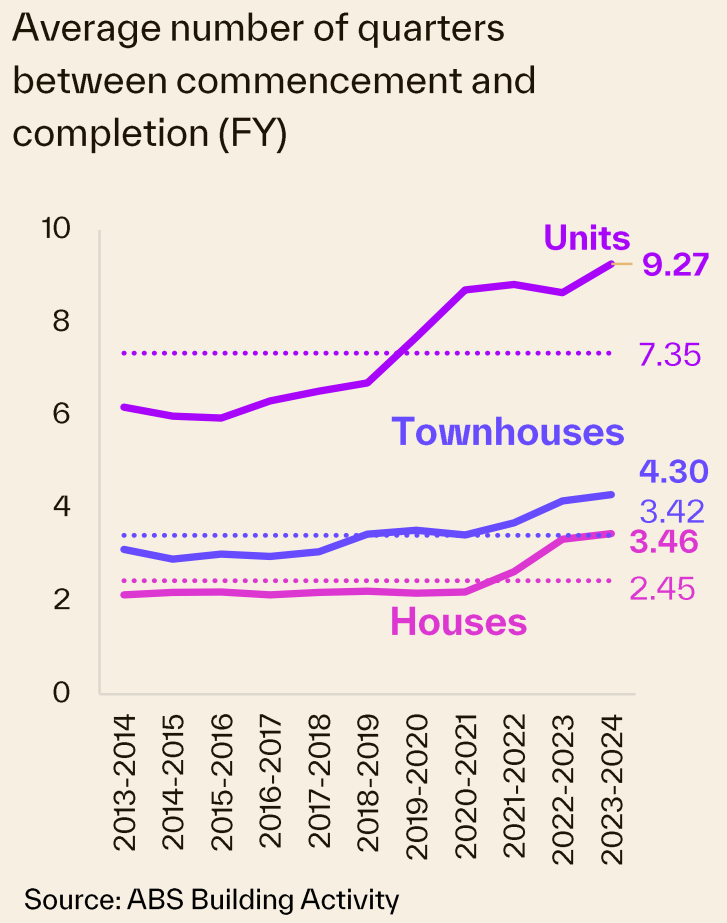

The average time to complete new housing has increased significantly:

“Trying to extract more houses from an industry with declining productivity is like filling a bucket with a widening hole”, Ai Group CEO Innes Willox said. “Without action to turn around this decade-long decline, Australia has little chance of meeting its targets, or ensuring affordable and secure housing for our changing population”.

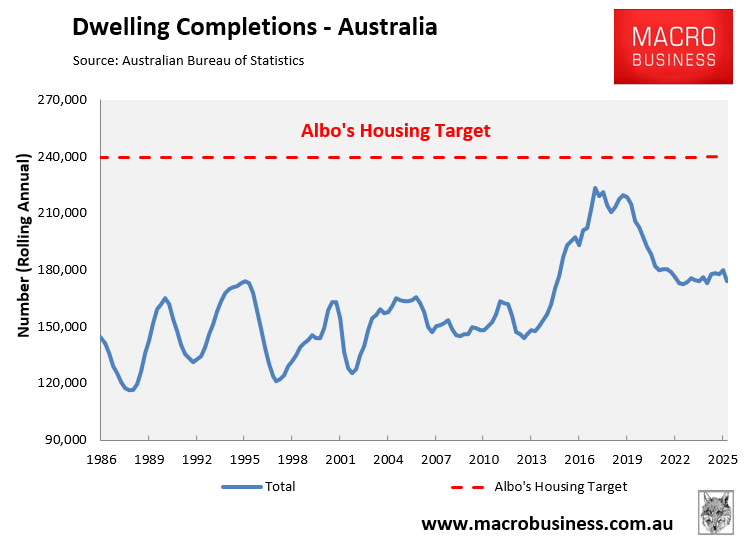

Indeed, the collapse in productivity comes at the same time as the Albanese government is seeking to build 1.2 million homes over five years—a target that in its first year was already running around 60,000 homes behind.

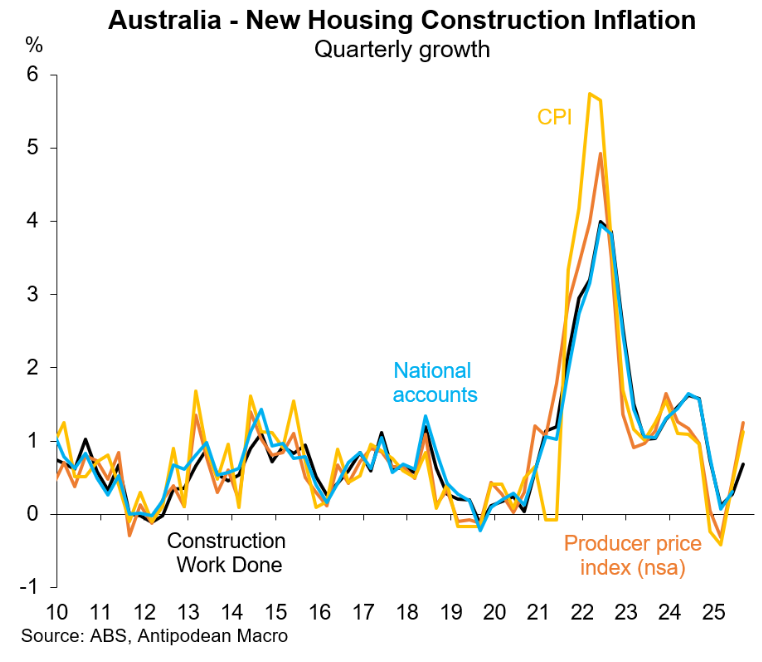

It also comes amid a circa 40% rise in construction costs since the pandemic, which have recently reaccelerated, as illustrated below by Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro:

It appears that a proliferation of administrators in suits has driven much of the decline in construction sector productivity.

Analysis released last year by RLB Oceania showed that professional workers had risen from 28% of the construction workforce in 2003 to 38% in 2023.

As a result, the industry has too many back-office suits and not enough people working the tools on the front lines.

This growth of suits also accounts for most of the decline in productivity across the construction industry:

“The growth in professional employees—professionals with tertiary degrees and building technicians with advanced diplomas—surged, rising 125% over the two decades from 242,900 to 547,300”, The AFR’s Michael Bleby wrote.

“But the annual output per professional worker fell 17.2% to $470,900 from $568,900”.

To be fair, output per worker has also fallen for tradies and labourers over the past decade. And this will have to improve for Australia to meet its housing and infrastructure delivery goals.

However, much like the broader Australian economy, the construction industry has become unbalanced and bogged down in bureaucracy and administration.

To make matters worse, Australia’s mass immigration policy is adding massively to the demand for housing and infrastructure, without helping to supply the nation with workers to deliver the required projects.

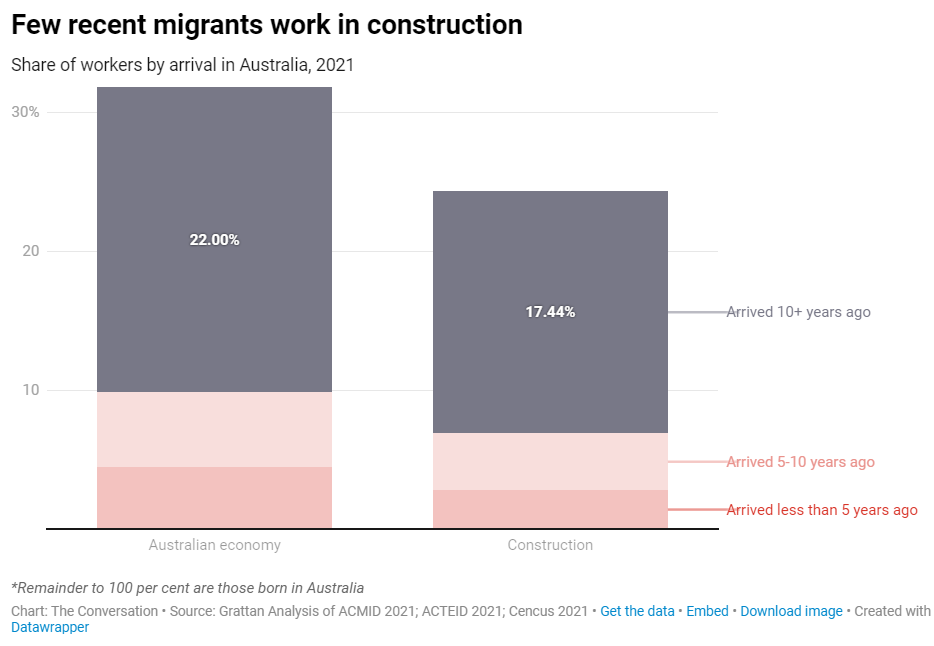

Build Skills Australia’s recent report claimed that there simply aren’t enough tradespeople to meet Labor’s housing targets and cautioned that few recent migrants actually work in construction:

Over the last 20 years, the residential construction sector has consistently employed between 4.0% and 5.0% of the working-age population in Australia.39 This ratio offers a reasonable benchmark for the level of labour resourcing required to meet housing needs. It implies that for every 100 new residents, 4–5 additional residential construction workers are required to support their housing needs.

If immigration is to make a net positive contribution to labour supply, the proportion of immigrants employed in residential construction must exceed this ‘hurdle rate’ of 4.0%-5.0%. Otherwise, local resources will need to be diverted from other activities to meet the housing needs of the growing population.

However, only 3.2% of recent immigrants—those who arrived in the last decade—are employed in the residential construction sector. This indicates that immigration’s contribution to population growth has not been matched by its contribution to the workforce needed to construct housing for these additional residents…

This dynamic highlights the importance of aligning migration settings with labour market demands. As it stands, the residential construction share of the immigration intake must increase by as much as 40% before it can be considered a viable strategy for boosting labour supply.

Build Skills Australia’s analysis aligns with data compiled by the Grattan Institute, which showed that migrants are heavily underrepresented in the construction industry:

“Migrants who arrived in Australia less than five years ago account for just 2.8% of the construction workforce, but account for 4.4% of all workers in Australia”, Grattan reported.

The solution, therefore, also requires running a significantly smaller migration program that prioritises quality over quantity and fills genuine skills shortages (e.g., tradies over Uber drivers).

Otherwise, Australia’s housing and infrastructure shortages will continue to worsen.