ABS admits education export figure is wildly exaggerated

For years, MB has argued that the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) estimate of education exports is wildly exaggerated because it:

- Incorrectly includes income from international students working in Australia.

- Does not adjust for remittances sent home from Australia by international students or former students (which are an import).

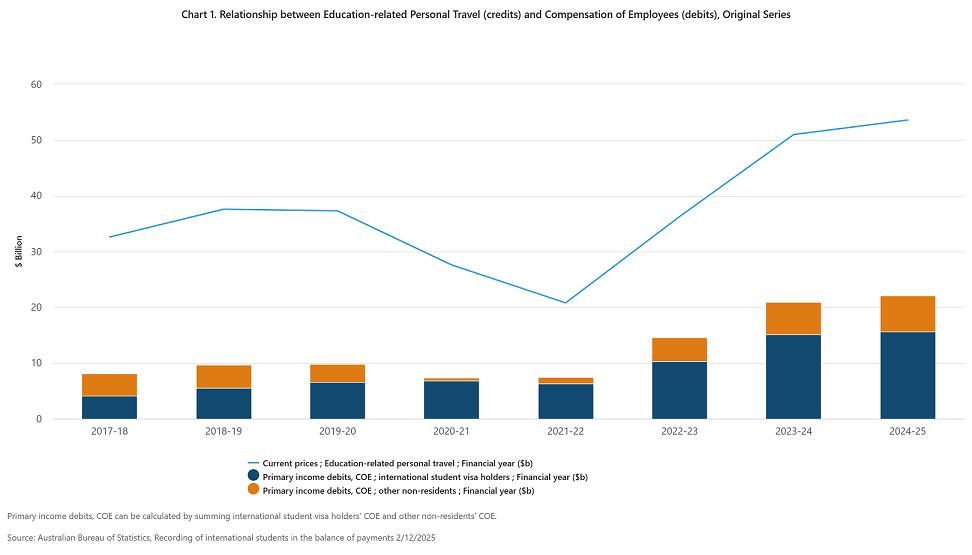

The ABS estimates that education exports hit a record high of $53.6 billion in 2024-25:

However, to its credit, the ABS has released a note explaining that this education export figure is exaggerated because it counts all expenditures in Australia by student visa holders regardless of where the money is earned. The ABS also estimates that around one-third of this expenditure was earned in Australia:

All expenditure by international students studying in Australia is recorded as an export in the Balance of Payments statistics published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. This includes expenditure on tuition fees, food, accommodation, local transport, health services, etc., by international students while in Australia. This expenditure contributed $53.6 billion to Australia’s exports in the 2024-25 financial year.

The classification of expenditure by international students studying in Australia as an export does not depend on how the students fund their expenditure in Australia. Some of the expenditure is funded from overseas sources. ABS estimates around a third of the expenditure ($15.6 billion in the 2024-25 financial year) is funded by international students working in Australia for Australian employers.

This classification of international students’ expenditure is determined by international standards specified in the International Monetary Fund’s Balance of Payments Manual and is widely adhered to across the globe.

We know that a significant share of international students work off-the-books for cash. Therefore, the true amount of income earned by students in Australia would be higher (meaning exports would be lower).

The ABS also explains that remittances are not captured in the balance of payments figures that are used to estimate education exports:

Personal transfers of cash or in-kind (sometimes referred to as workers remittances) between residents and non-residents are recorded under secondary income. However, if an international student receives funds from their non-resident parents who live overseas, or if the student transfers funds back to their home economy, both of these transactions would be out of scope of Australia’s balance of payments as they are transactions between non-residents.

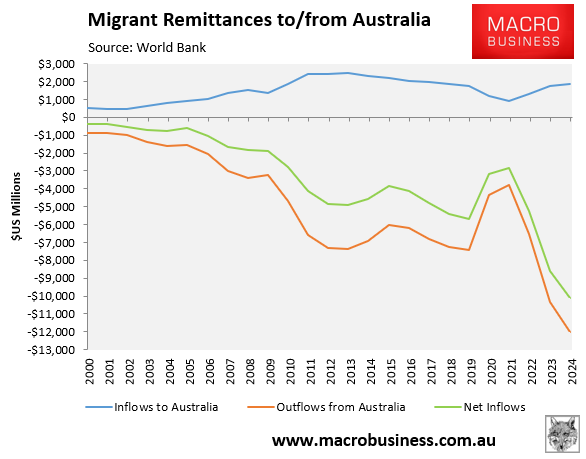

This omission is important because, according to the World Bank’s most recent data on migrant remittances, net remittance outflows from Australia totalled $US10.1 billion in 2024, or around $A15 billion:

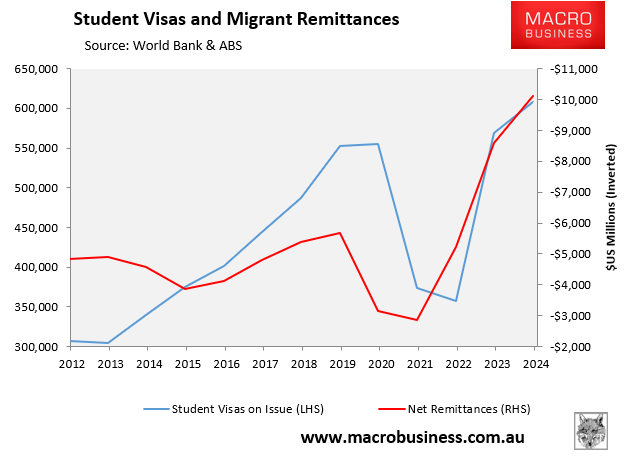

The volume of net remittance outflows has also tracked the number of international students studying in Australia.

Indeed, Jobs & Skills Australia’s (JSA) latest report on the international education system stated that over 90% of Indian and nearly 96% of Nepali higher education students cited the ability to work while studying as one of the reasons they chose Australia. “80% of students from South and Central Asia (including India and Nepal) were working during study”, JSA said.

JSA also noted that many Indian students send money back to their home countries via remittances.

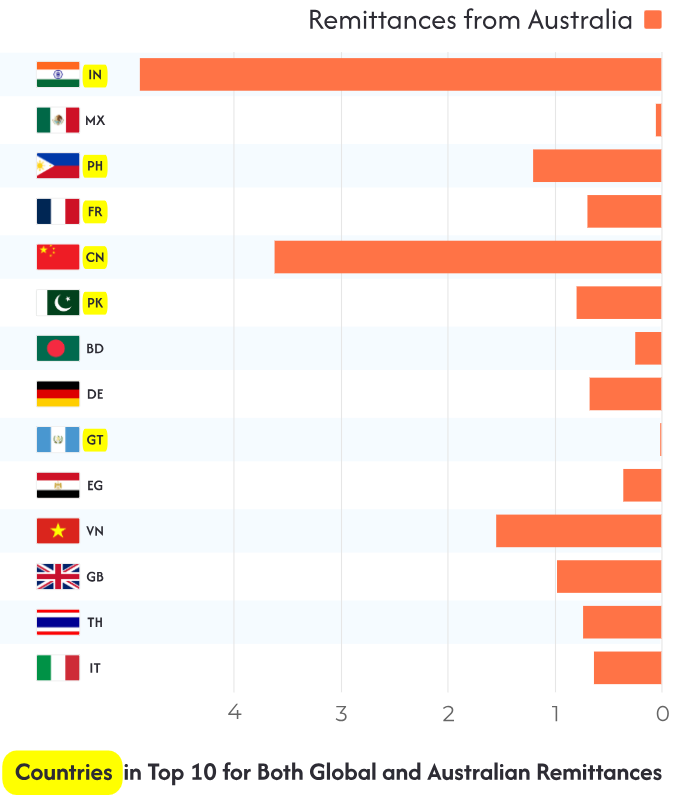

A recent report from Money Transfer Australia, which drew on data from the World Bank, ABS, KNOMAD, and DFAT, estimated that US$4.8 billion worth of remittances were sent to India from Australia in 2024.

Source: Money Transfer Australia

“Money Transfer Australia’s report highlights that migrants from India are among the most active senders of money, despite the diversity of Australia’s overseas-born population”.

Indian Link projected that remittance outflows to India will continue to rise as the migrant population expands in Australia, driven by international education.

The ABS also provides the following examples explaining how the current account captures international education:

Example 1:

Sam, an international student studying at an Australian university, spends $100,000 on goods and services from Australian businesses (for tuition fees, food, accommodation, transport, and so on). Sam also has a part-time job while studying in Australia and earns $20,000 in wages from an Australian employer.

The $100,000 Sam spent is an export of education-related Travel services and recorded as a ‘service export’ (credit) in the trade balance. The $20,000 Sam earnt in wages is recorded as compensation of employees debits in the primary income balance. Sam’s net impact on the Current account is $80,000.

Example 2:

An Australian university pays $10,000 to a non-resident business to advertise their courses to potential international students.

The $10,000 the Australian university spent is an import of ‘Other business services: professional and management consulting services’ and is recorded as a ‘service import’ (debit) in the trade balance. The net impact of this transaction on the Current account is -$10,000.

So basically, education exports include all expenditures by international students in Australia, whereas money earned by students and commissions paid by universities to foreign agents are netted off elsewhere in the current account. Money sent home by students is also not counted.

The bottom line is that the headline education export figure quoted by the ABS is grossly exaggerated and should be discounted by:

- Money earned by students in Australia (both formal and informal);

- Remittances sent home; and

- Commissions paid by universities and colleges to foreign agents.

For transparency purposes, the ABS should include a footnote noting that education exports are a gross figure and do not account for income earned in Australia by students, remittance outflows, or commissions paid by universities to foreign agents.

The government, media, and industry should also stop quoting this fantastical figure as fact.