The great housing bubble hits new milestone

The Great Australian Housing Bubble hit a new milestone in October, reaching an all-time high valuation of $12.0 trillion, according to Cotality.

“This unprecedented value is more than double the market’s size a decade ago, with the majority of the growth occurring over the past five years”, Cotality Economist Kaytlin Ezzy said.

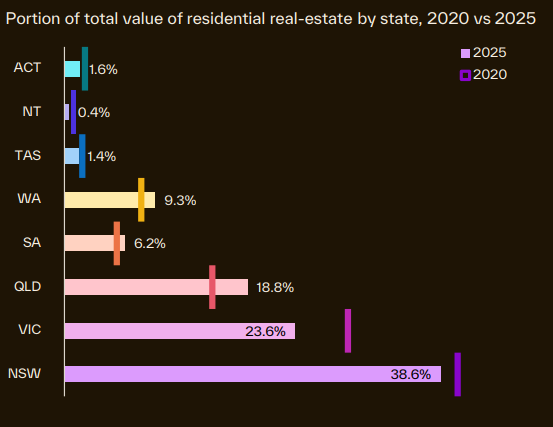

“Interestingly, the composition of this value has shifted geographically, with South Australia, Western Australia, and Queensland picking up a larger share of the combined housing value, while New South Wales and Victoria make up a smaller share than five years ago”.

Ezzy added that Victoria’s share of the nation’s housing stock has declined from 29% five years ago to “less than a quarter” now.

Australia’s $12.0 trillion housing valuation is spread across 11.4 million dwellings, equating to a value of $1,052,600 per dwelling.

Dividing $12.0 trillion by Australia’s current population of 27,814,740, as per the ABS Population Clock, gives a per capita housing value of $431,426.

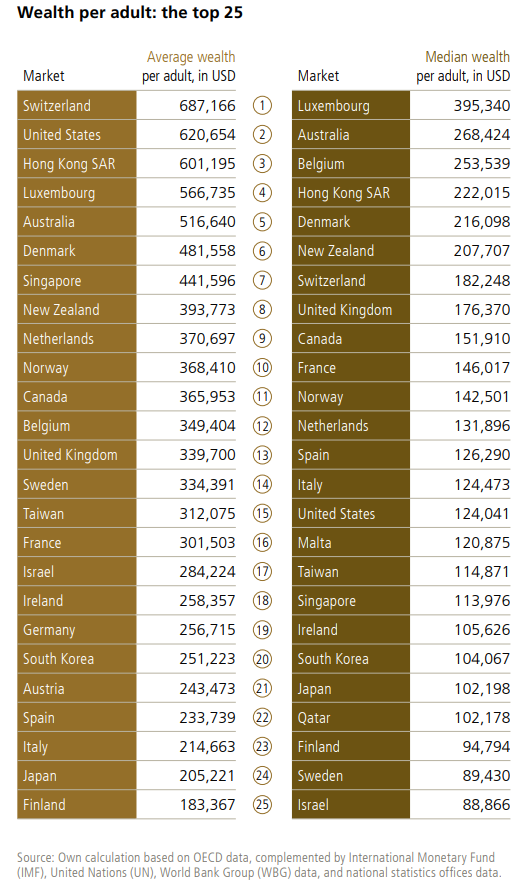

This is an extraordinary sum of ‘wealth’ stored in housing, which largely explains why Australians rank near the very top of global rankings on household wealth:

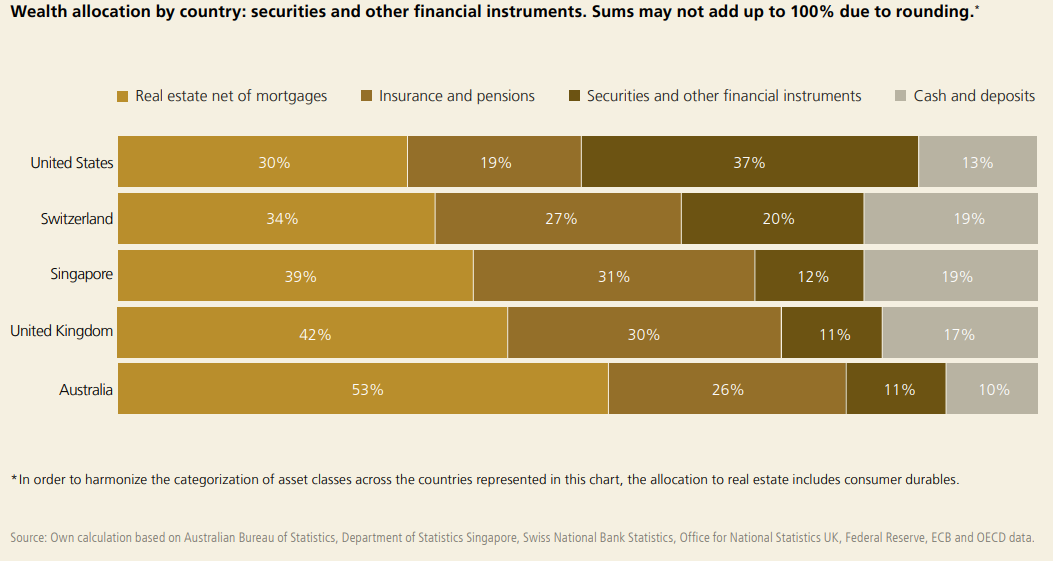

Australia also stands apart from most other nations, since it stores more than half of its household wealth in illiquid residential property:

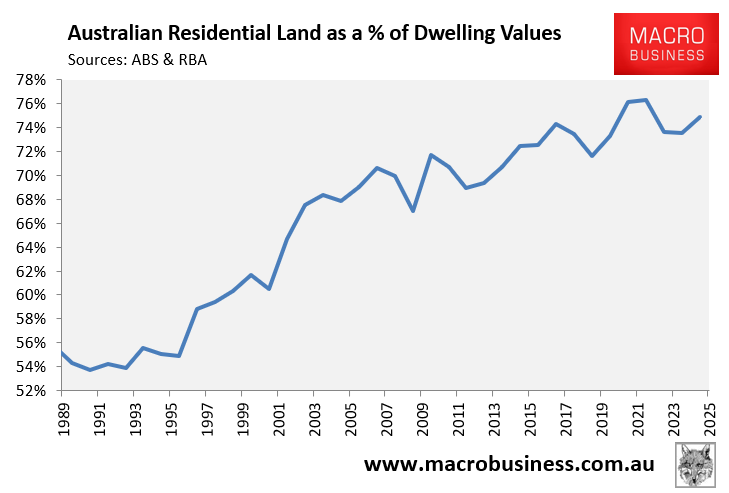

As I pointed out last week, the rise in the value of Australia’s dwelling stock has been driven by soaring land values.

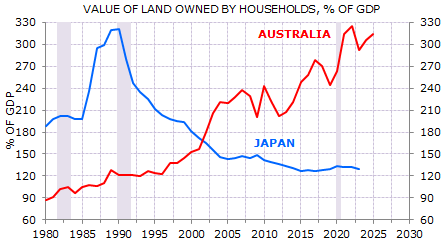

As illustrated below by independent economist Gerard Minack, Australia’s total residential land valuation as a percentage of GDP is now on par with Japan’s at its peak during the late 1980s land bubble:

Source: Gerard Minack

If Japan’s housing market was considered a giant bubble in the late 1980s, surely Australia’s should also be considered a “bubble” now?

Let’s face it: the majority of Australia’s wealth is fake.

Higher home values offer little benefit for owner-occupier households, which only need a place to live.

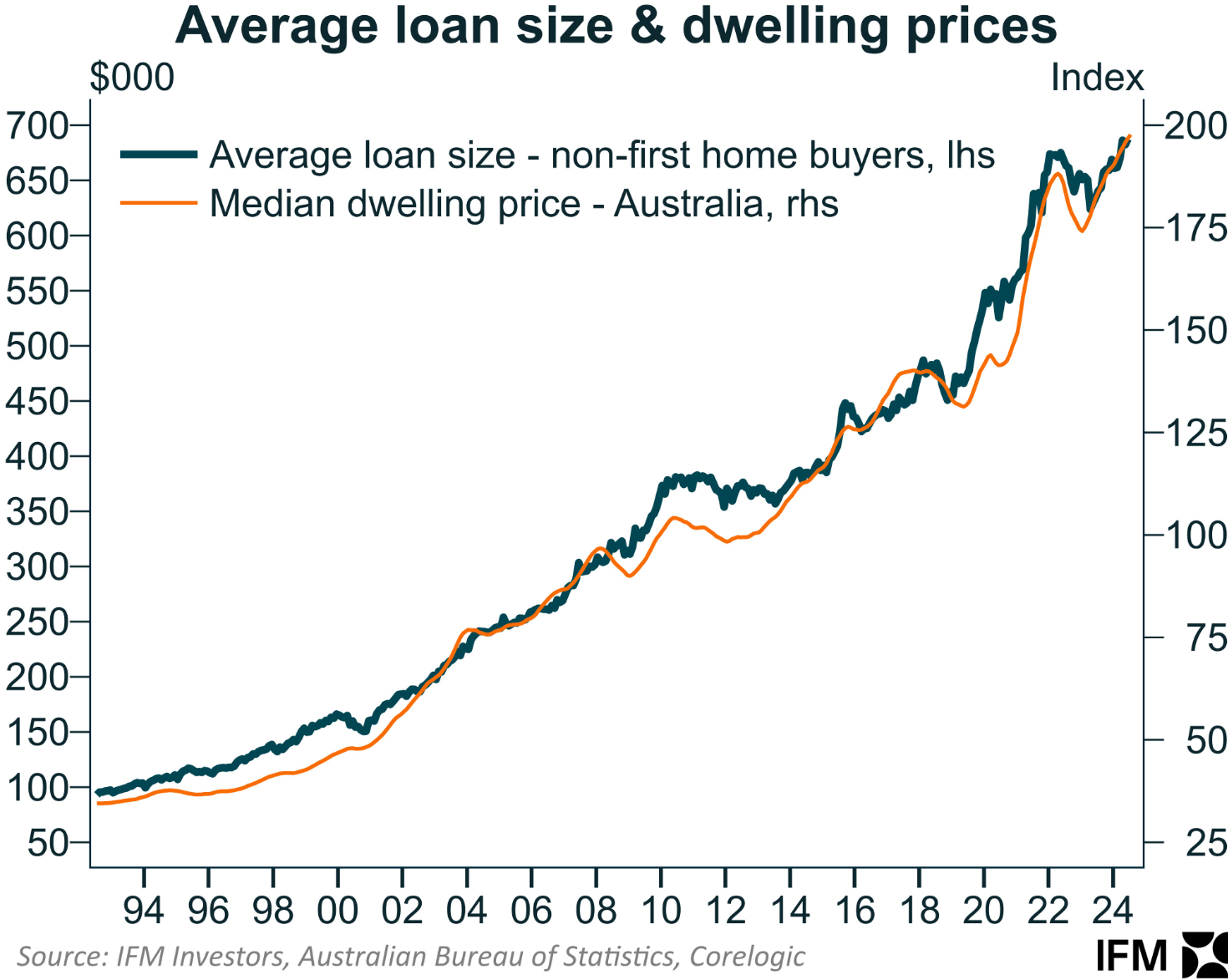

Australians are being suffocated by the need to take on ever-larger mortgages to cover rising housing costs.

Australia would be a far more equitable nation, and residents would be financially better off if the average home were worth $525,000 instead of $1,050,000, and household debt were 90% of income rather than 180%.

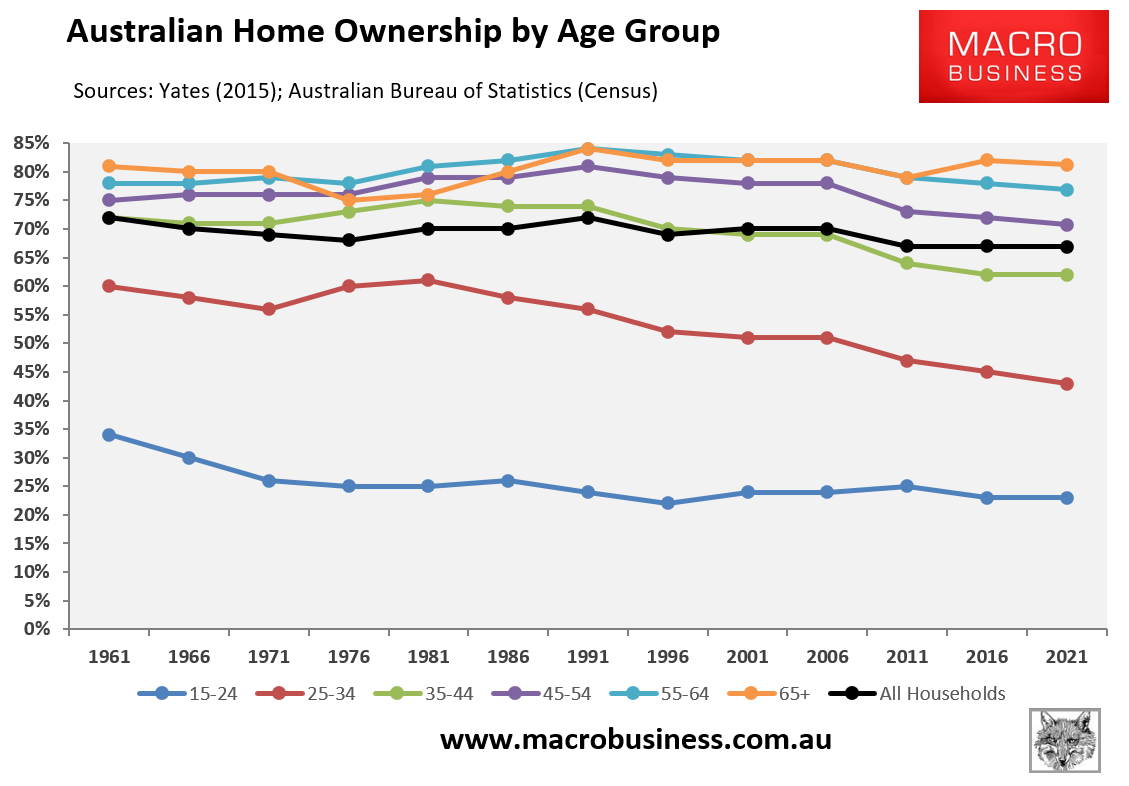

According to the 1991 Census, Australia’s homeownership rate was about 5% higher than it is now. Homes cost roughly three times income (compared to eight times today), and household debt was 70% of income, compared to 180% today.

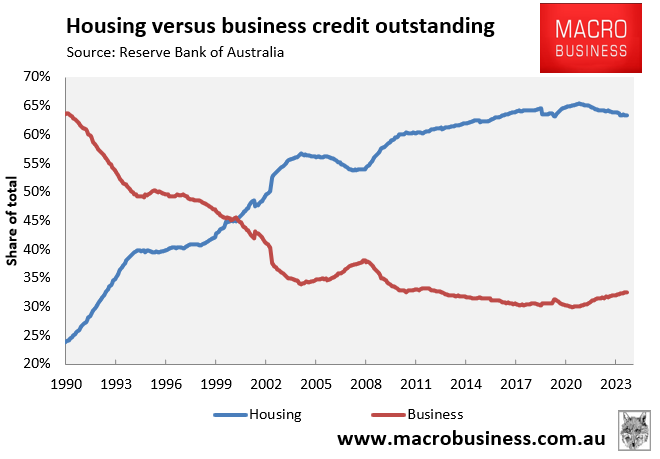

Banks also lent about two-thirds to businesses and one-quarter to mortgages, the opposite of today:

Despite having significantly less property wealth, Australian households were financially better in 1991 than they are today. The Australian economy was likewise far more balanced, diverse, and productive in 1991 than it is today.

Ultimately, Australia’s continually rising home prices and mortgage debt represent a significant misallocation of resources that has harmed productivity, equity, and the overall economy.

The Australian economy needs productive investment and capital deepening, not forever-rising housing prices.