So, you still think international education is a major export?

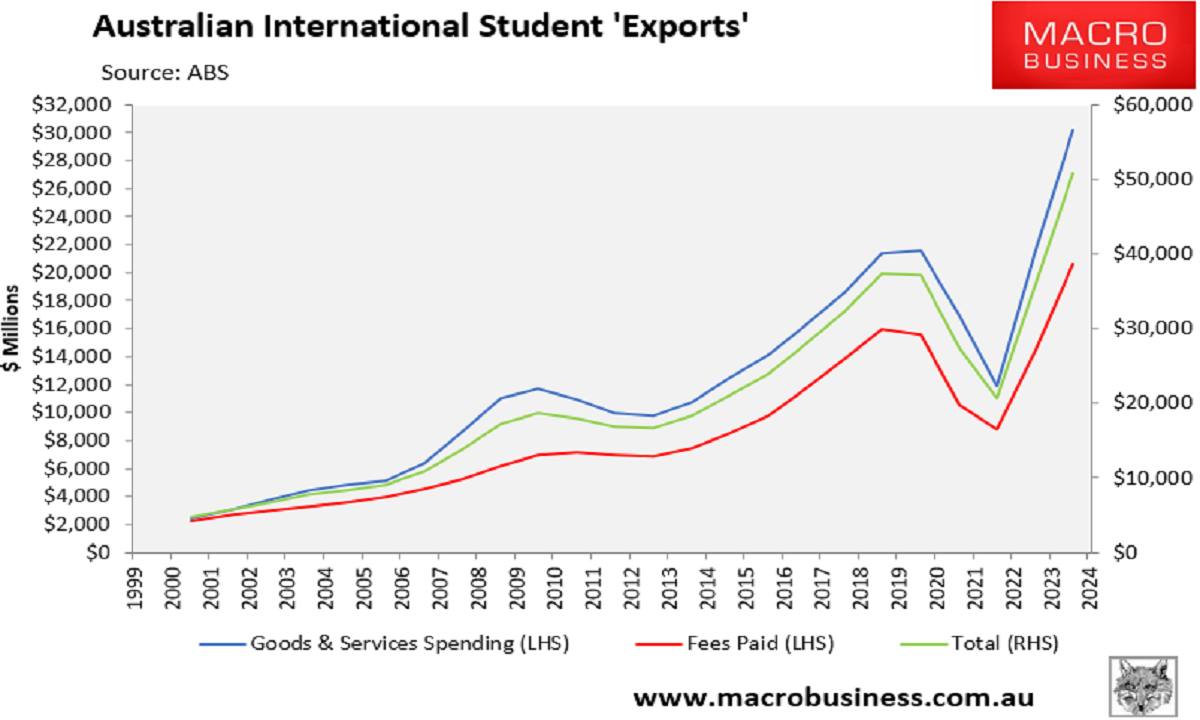

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) reports that international education is Australia’s fourth-largest export, earning the country $51 billion in 2024.

The ABS generates this fantasy “export” figure by summing student visa holders’ spending on tuition fees and goods and services.

In 2024-25, the ABS estimated that student visa holders spent $30.2 billion on goods and services and $20.6 billion on tuition fees.

The ABS’ $51 billion education export figure is significantly exaggerated for two reasons.

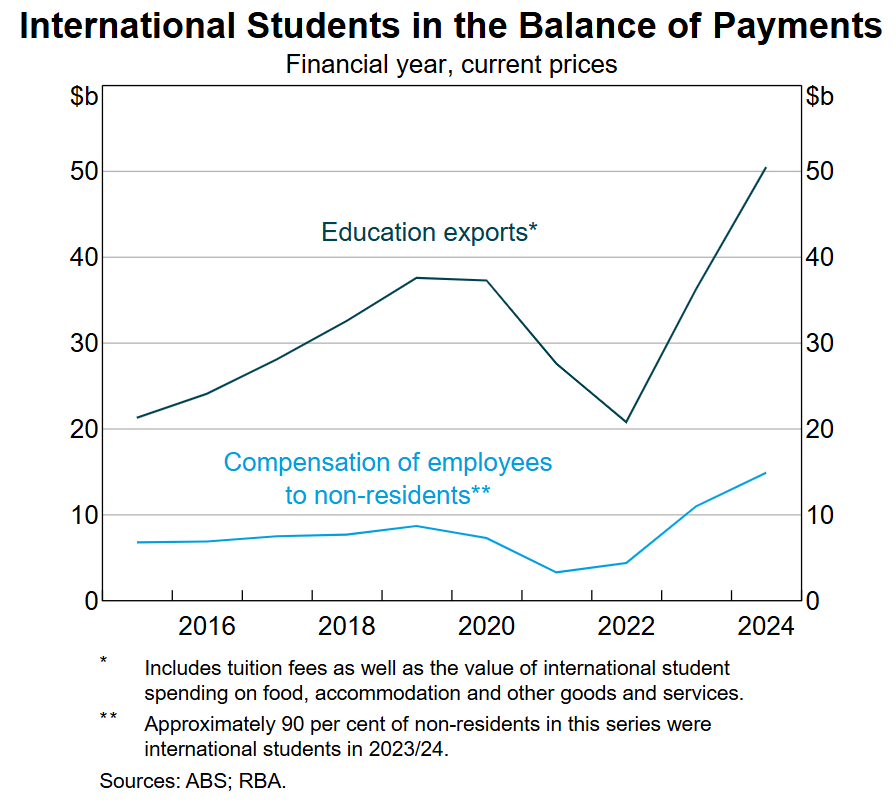

First, it excludes money earned by students working in Australia, which is not an export.

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) reported that international students working in Australia earned $13.4 billion in 2023-24.

The RBA estimated that in 2024, “the average international student worked around three-quarters of the hours of an average member of the working age population, and around the same hours as an average member of the total resident population”.

“The propensity of international students to work varies by country of origin, with students from India and Nepal typically having higher rates of labour force participation”.

The RBA also admitted that its estimate of earnings is conservative, given “survey evidence [shows] that temporary migrants are much more likely to be paid below-minimum wages, meaning cash-in-hand work may be prevalent”. Therefore, international students are likely to earn money in the informal economy.

University of Sydney Associate Professor Salvatore Babones, who authored the 2021 book Australia’s Universities: Can They Reform?, also cautioned that international student earnings were likely significantly underestimated, since gig economy jobs like UberEats were not captured in the data.

Digital service platforms like Uber Eats only became legally required to report income earned by users to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) on 1 July 2024 under the Sharing Economy Reporting Regime (SERR).

“We just don’t have any data on how many are working in the gig economy”, Babones said.

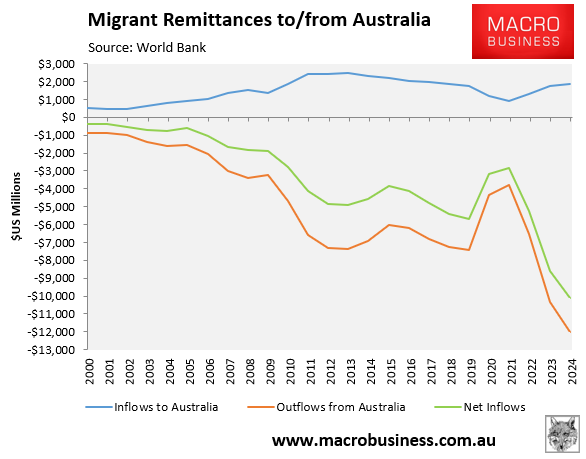

Australia’s $51 billion education export figure also does not deduct money returned home as remittances by international students and former students, which is an import.

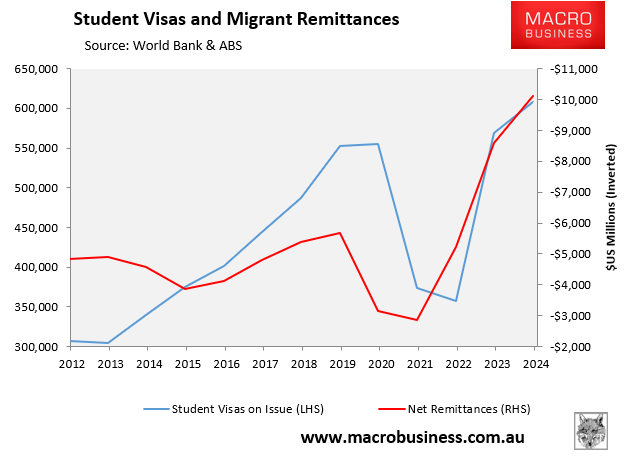

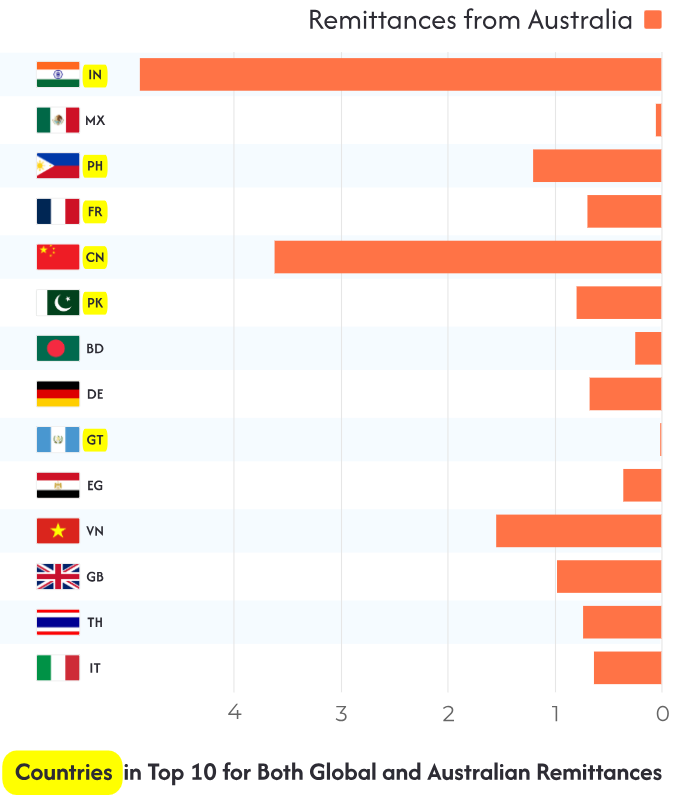

According to the World Bank’s most recent data on migrant remittances, net remittance outflows from Australia totalled $US10.1 billion in 2024, or around $A15 billion.

The volume of net remittance outflows has also tracked the number of international students studying in Australia.

Indeed, Jobs & Skills Australia’s (JSA) latest report on the international education system stated that over 90% of Indian and nearly 96% of Nepali higher education students cited the ability to work while studying as one of the reasons they chose Australia. “80% of students from South and Central Asia (including India and Nepal) were working during study”, JSA said.

JSA also noted that many Indian students send money back to their home countries via remittances.

A recent report from Money Transfer Australia, which drew on data from the World Bank, ABS, KNOMAD, and DFAT, estimated that US$4.8 billion worth of remittances were sent to India from Australia in 2024.

Source: Money Transfer Australia

“Money Transfer Australia’s report highlights that migrants from India are among the most active senders of money, despite the diversity of Australia’s overseas-born population”.

Indian Link projected that remittance outflows to India will continue to rise as the migrant population expands in Australia, driven by international education.

With this background in mind, it was interesting to read a report in the ABC explaining how international students are circumventing Australia’s financial requirements on student visas, leaving them struggling to make ends meet.

The article profiles 21-year-old Indian student Alipriya Biswas, who proved that she had access to $30,000 for living costs and secured her visa, but her family has refused to release the money, leaving her stranded financially.

“Many people think we come here with endless money from rich families and have everything set up when we get off the plane”, she said. “But that’s not true”.

Professor Alan Morris from the University of Technology, Sydney, said that 78% of students from low-income countries relied on paid work for their main income.

“Those students that come from low-income families [are] especially vulnerable because they can’t go back to their parents necessarily and ask for more money”, Professor Morris said.

“Some students find themselves working two to three jobs and of course their academic results suffer dramatically”.

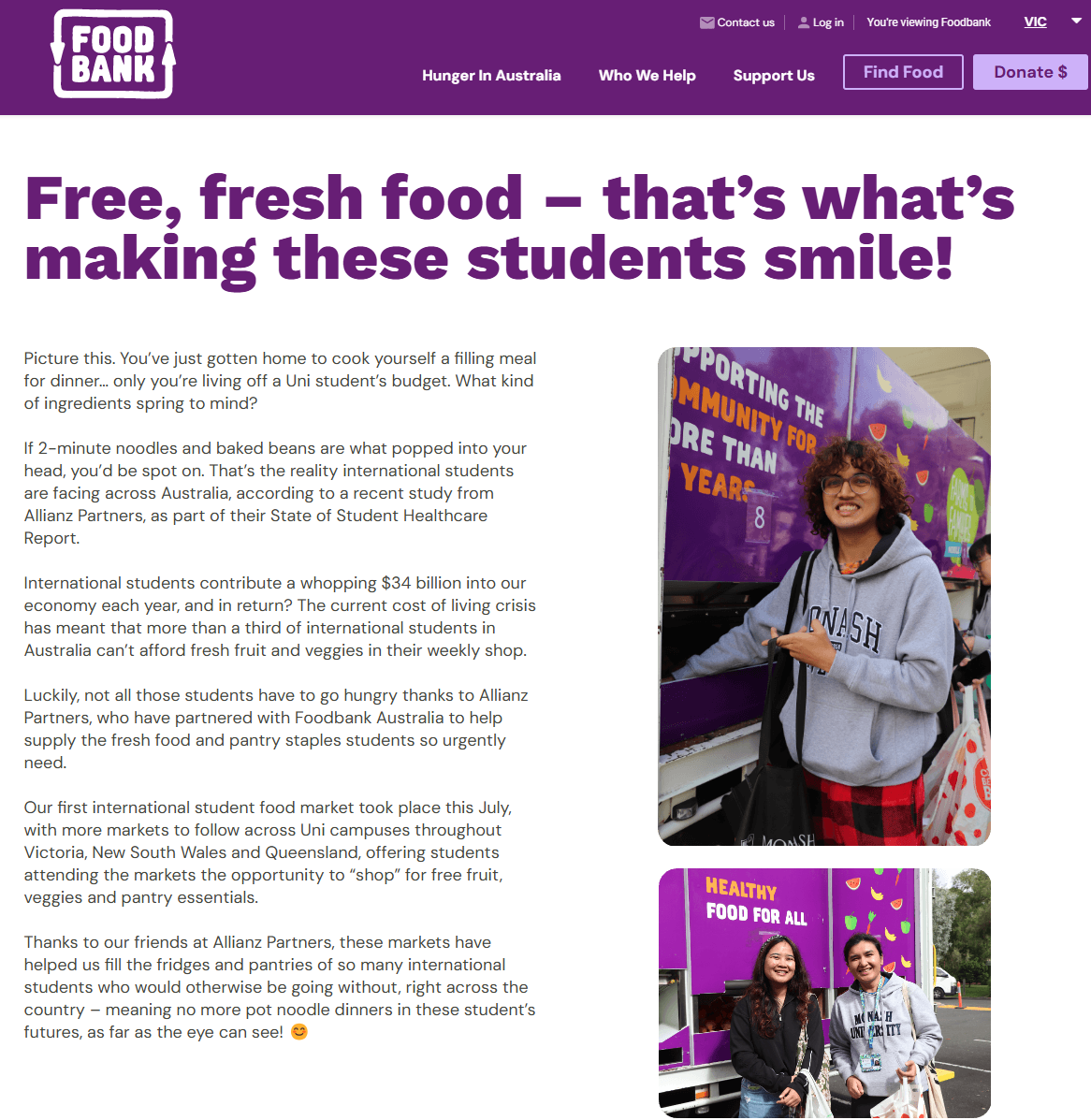

Numerous reports have emerged recently of ‘desperate’ international students relying on food banks.

For example, Allianz Partners announced that it had partnered with Foodbank Australia “to help alleviate the burden of financial hardship and food insecurity among international students studying in Australia”.

“The current cost of living crisis has meant that more than a third of international students in Australia can’t afford fresh fruit and veggies in their weekly shop”, the media release read.

“The rising cost of living has led international students to rely on charitable organisations to meet their most basic needs, emphasising the need for further support”, Miranda Fennell, Executive Head of Health and International Student Wellbeing Spokesperson, said.

The SMH reported that “demand for the University of Sydney’s student-run food welfare service, FoodHub, which offers free food and essential items such as toiletries, rose 60% in the past year, with international students making up 93% of the 57,000 students who used the service in 2024”.

Queues for Sydney University’s food bank stretch outside the door. Almost all were international students.

Gaby Ramia, a professor of policy and society at the University of Sydney, has called on governments to provide international students with access to public transport concessions equal to domestic students, alongside access to healthcare benefits.

Clearly, the export value of international education has been wildly exaggerated.

Most work to cover their living expenses and compete for jobs with younger Australians, and some even rely on charity for financial support.

The situation will only worsen given the federal government has signed three agreements with India to boost student and migration flows:

- The Australia-India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement (ECTA), signed by the former Coalition government late in its final term.

- The Australia-India Migration and Mobility Partnership Agreement, signed by the Albanese government in its first term.

- The Mechanism for Mutual Recognition of Qualifications, signed by the Albanese government in its first term.

The federal government has also lowered India’s assessment level for Australian student visas as well as lowered the risk weightings on 15 Australian universities, making it easier to recruit international students.

As a result, the numbers of Indian students living, working, and sending money home from Australia will inevitably increase.