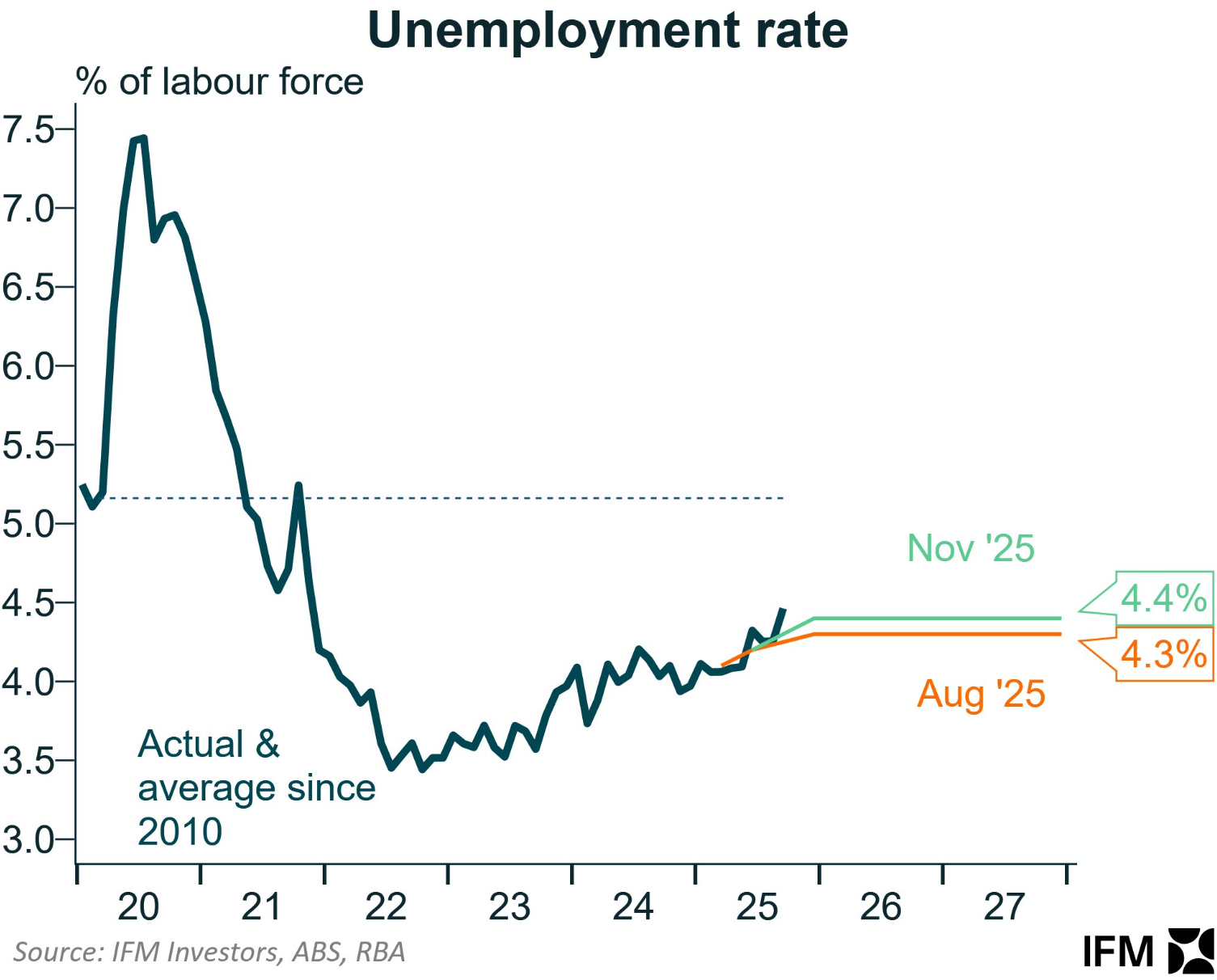

The Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) latest Statement of Monetary Policy (SoMP) revised its medium-term unemployment rate forecast to 4.4%, up from 4.3%.

As illustrated below by Alex Joiner from IFM Investors, the RBA’s unemployment rate forecast to the end of 2027 is slightly lower than the current unemployment rate of 4.5%:

Therefore, the RBA expects the unemployment rate to decline marginally from its current level over the next several years.

I explained last week why I believe that the RBA’s unemployment forecast is highly optimistic.

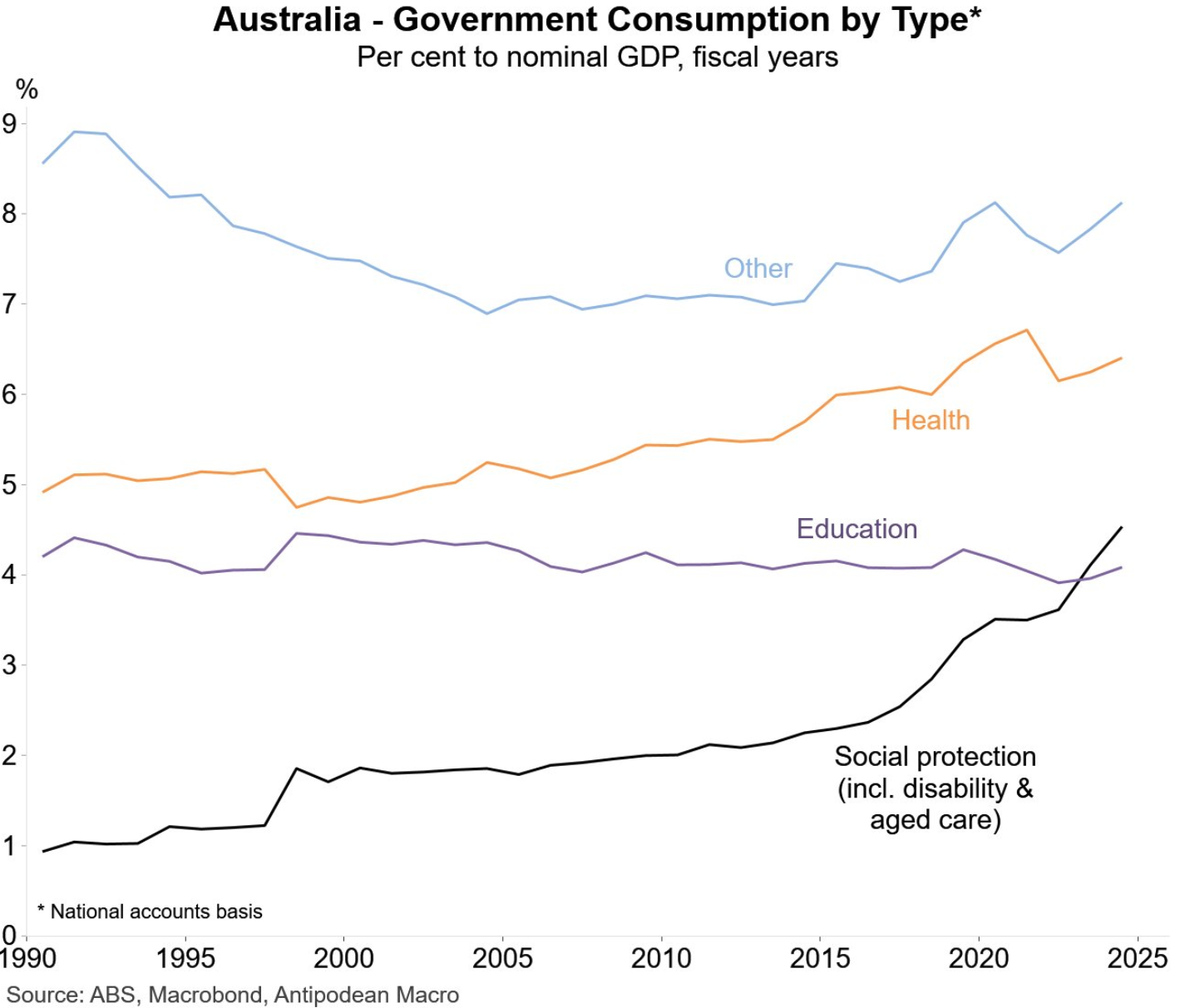

In a nutshell, most of Australia’s job growth since the pandemic has been driven by government spending through the non-market sector, primarily related to the expansion of the NDIS.

This rapid expansion of the non-market economy is unlikely to continue, given that federal and state governments face large budget deficits and are seeking to control costs.

Nor is the private (market) sector likely to expand enough to compensate for the slower growth in the non-market economy.

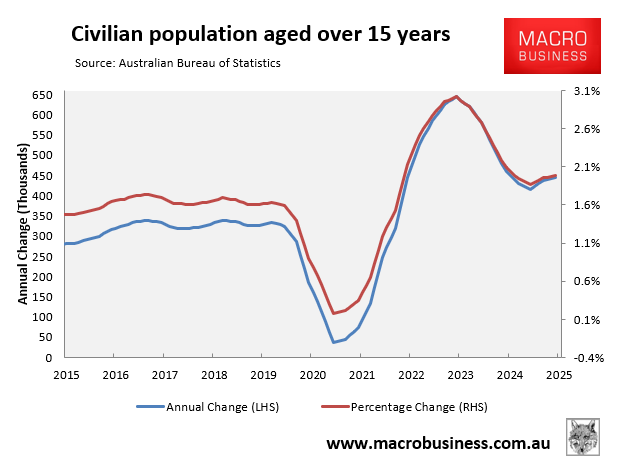

Add the ongoing strong growth in labour supply, driven by high immigration, and the ingredients are in place for rising unemployment.

For what it is worth, the latest batch of labour market indicators offers mixed signals for unemployment.

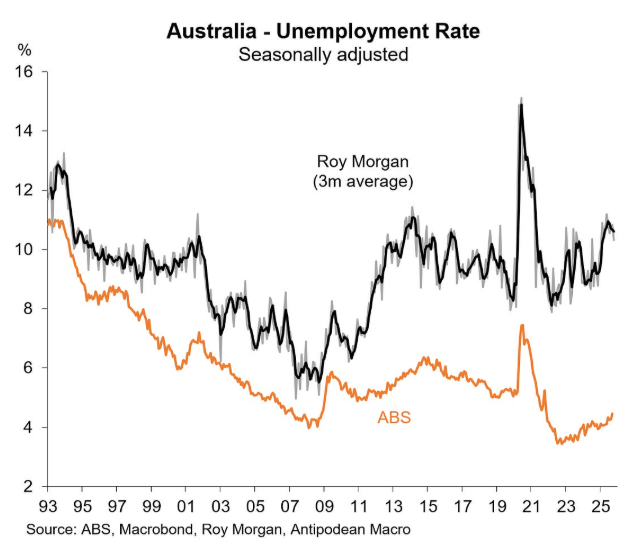

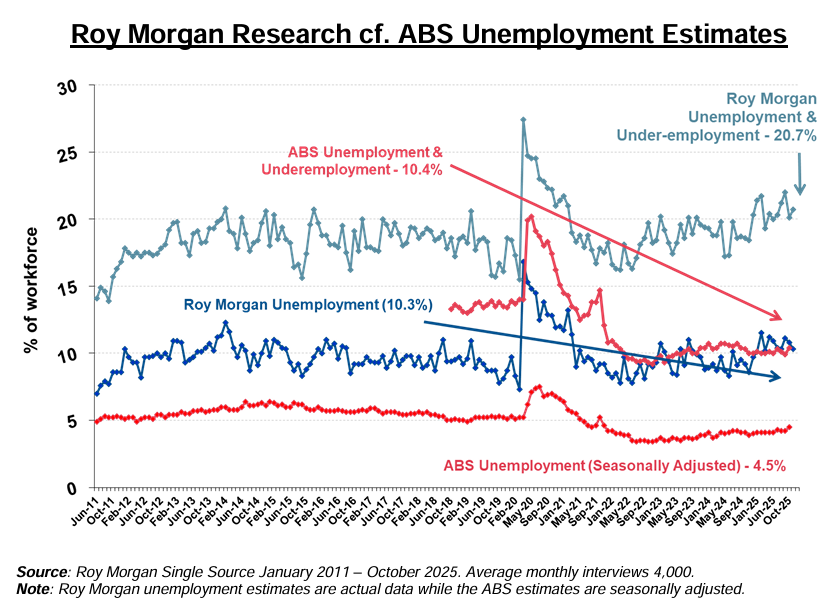

As illustrated below by Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro, Roy Morgan’s unofficial measure of unemployment declined in October to 10.3% and has now trended lower in 3-month average terms for several months:

However, Roy Morgan’s measure has still broken away from the ABS’s official measure and was 1.1% higher in October 2025 (10.3%) than in October 2024 (9.2%).

Roy Morgan has also recorded a significant rise in overall labour underutilisation (i.e., unemployment and underemployment combined):

Roy Morgan’s overall underutilisation rate was 20.7% in October 2025, up 2.1% from 18.6% in October 2024.

“The sluggish labour market—with no net jobs created compared to a year ago—shows the low level of productivity in the Australian economy is stifling growth and leading to labour market stagnation”, commented Michele Levine, CEO of Roy Morgan.

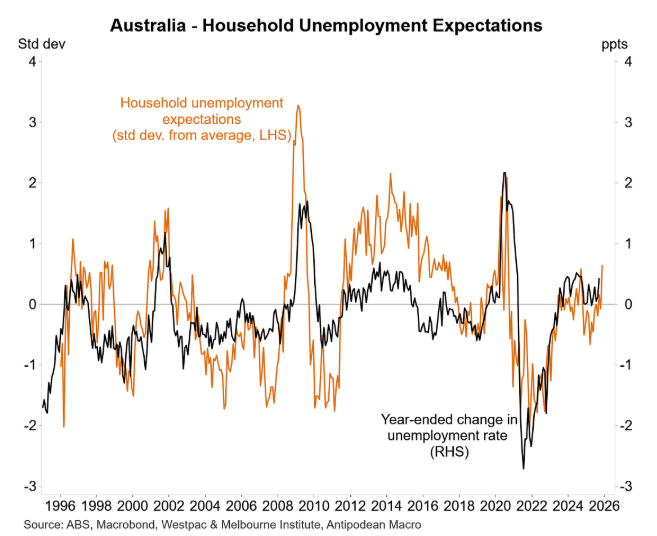

Meanwhile, the latest Westpac consumer sentiment survey showed that unemployment expectations have jumped, which has historically been a soft leading indicator of the official unemployment rate:

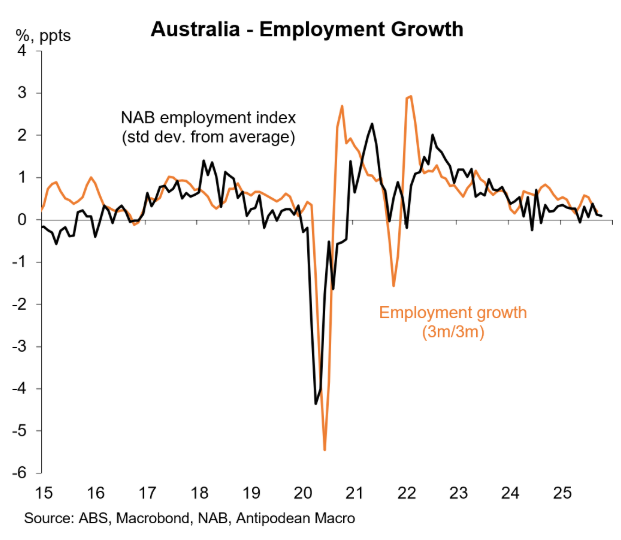

Fabo also shows that the NAB business survey employment index fell slightly in October and appears consistent with softer job growth:

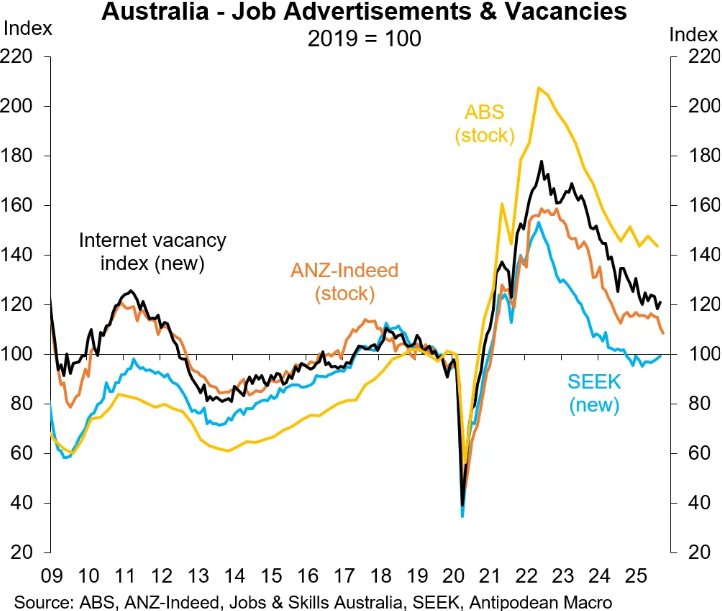

Finally, the various recent measures of job advertisements have fallen, suggesting weaker labour demand at the same time as labour supply continues to expand aggressively:

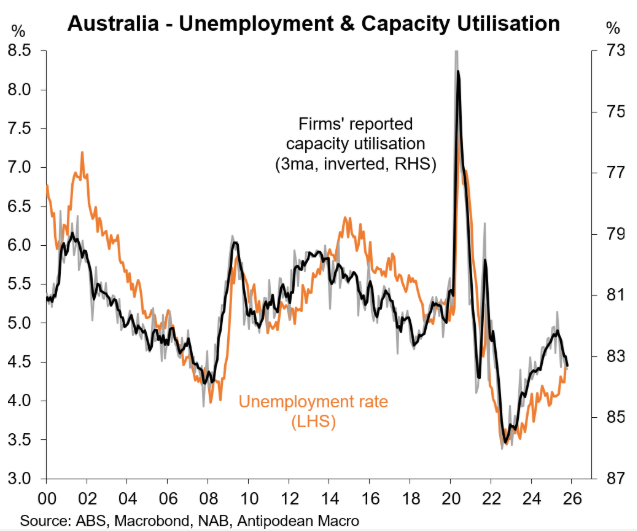

The one major ‘fly in the ointment’ to the view that the labour market is softening comes from the NAB business survey’s capacity utilisation measure, which, as Fabo shows below, has historically been “a useful leading indicator of underlying trends in the unemployment rate (which is similarly an indicator of capacity constraints)”:

“Recent increases in capacity utilisation (it’s inverted in the chart) point to the risk that the jobless rate could actually decline in coming months”, Fabo wrote.

Regardless, the weight of evidence suggests that the RBA’s 4.4% unemployment forecast is too optimistic.

The good news for mortgage holders is that if the unemployment rate rises significantly above the RBA’s forecast, it could prompt it to cut rates.

This is why I firmly believe that the next move in official interest rates is likely to be down. However, any cut is unlikely to arrive before the second quarter of 2026.