RBA still delusional on unemployment

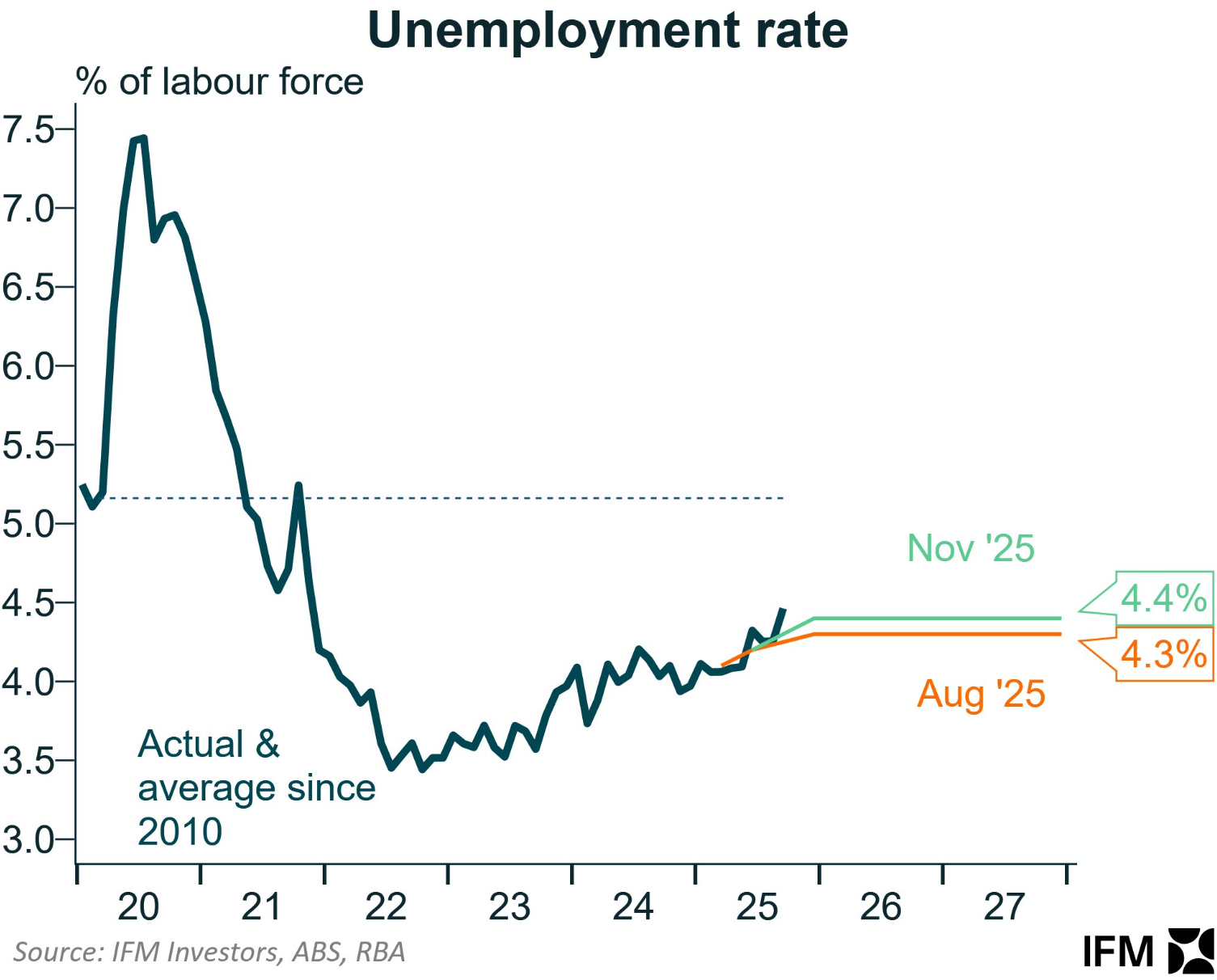

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) released its Statement of Monetary Policy (SoMP) this week, which revised its medium-term unemployment rate forecast to 4.4%, up from 4.3%.

As illustrated below by Alex Joiner from IFM Investors, the RBA’s unemployment rate forecast to the end of 2027 is below the current unemployment rate of 4.5%:

Thus, the RBA expects the unemployment rate to fall slightly from its current level and not deteriorate over the next several years.

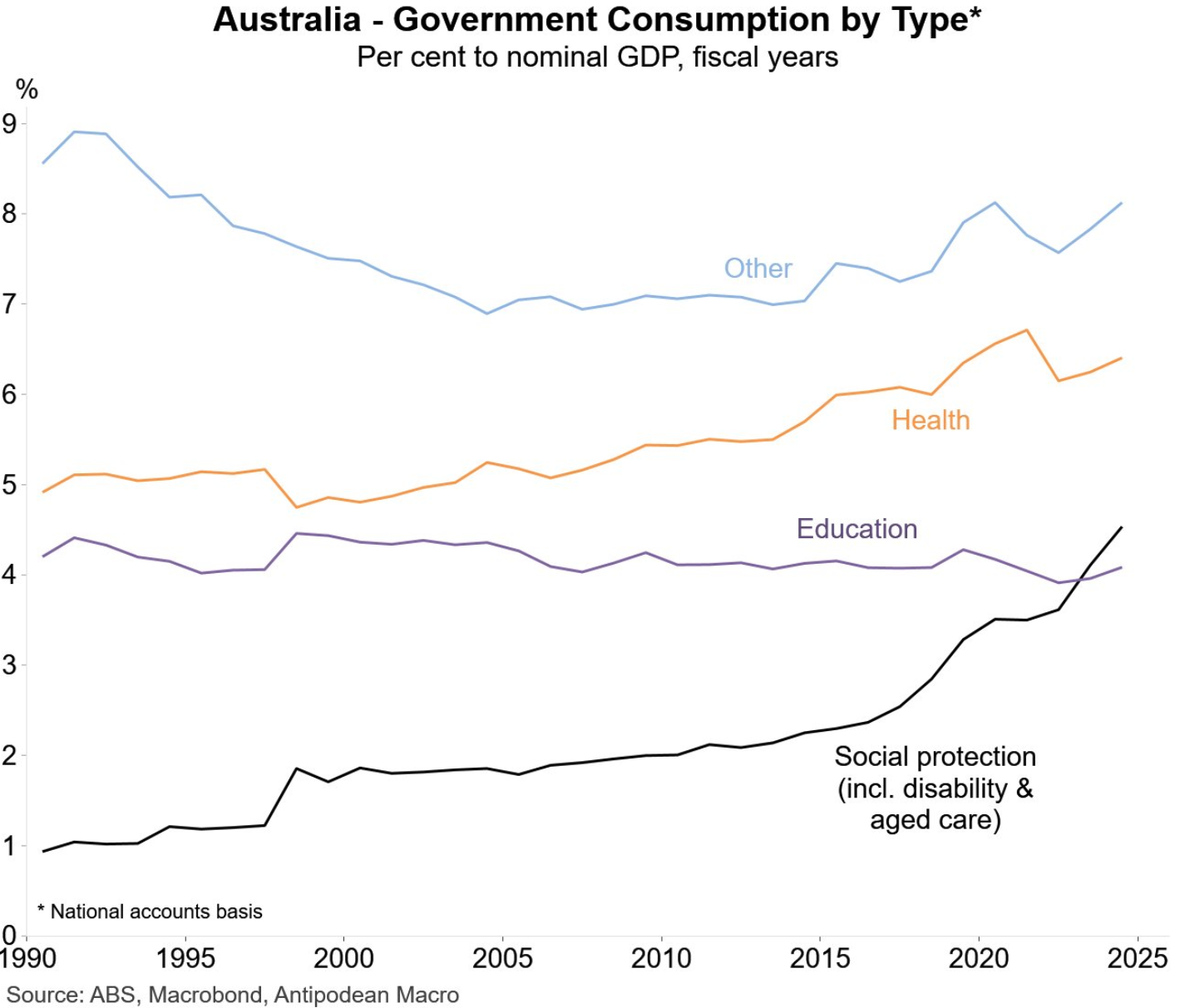

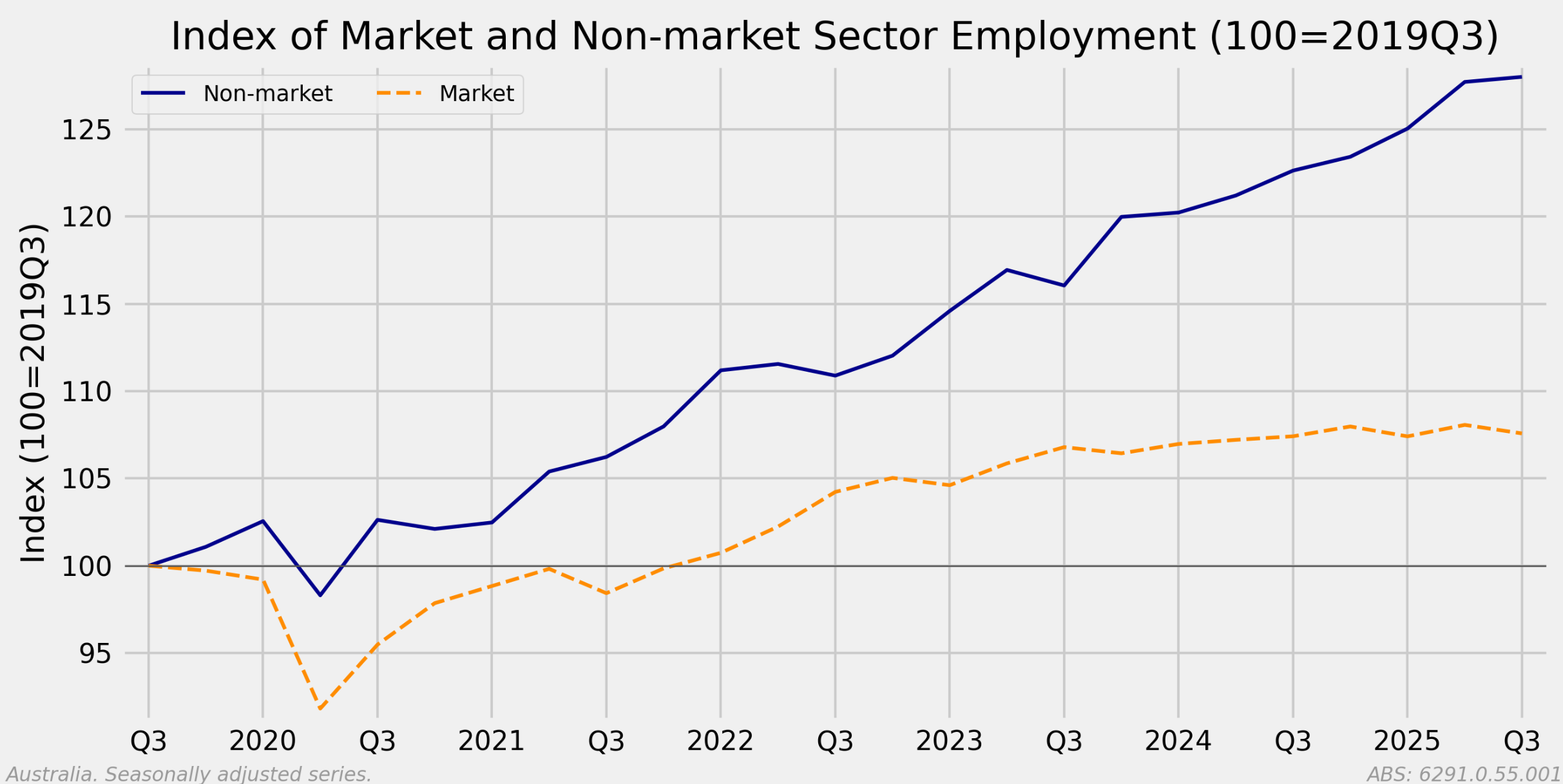

The RBA appears not to recognise that Australia’s job market has been artificially supported by the rapid expansion of non-market (government-funded) jobs, primarily related to the growth of the NDIS.

The following chart from Justin Fabo at Antipodean Macro shows that government spending on “social protection”, which encompasses social security, welfare, and disability supports, hit 4.5% of GDP in 2024-25:

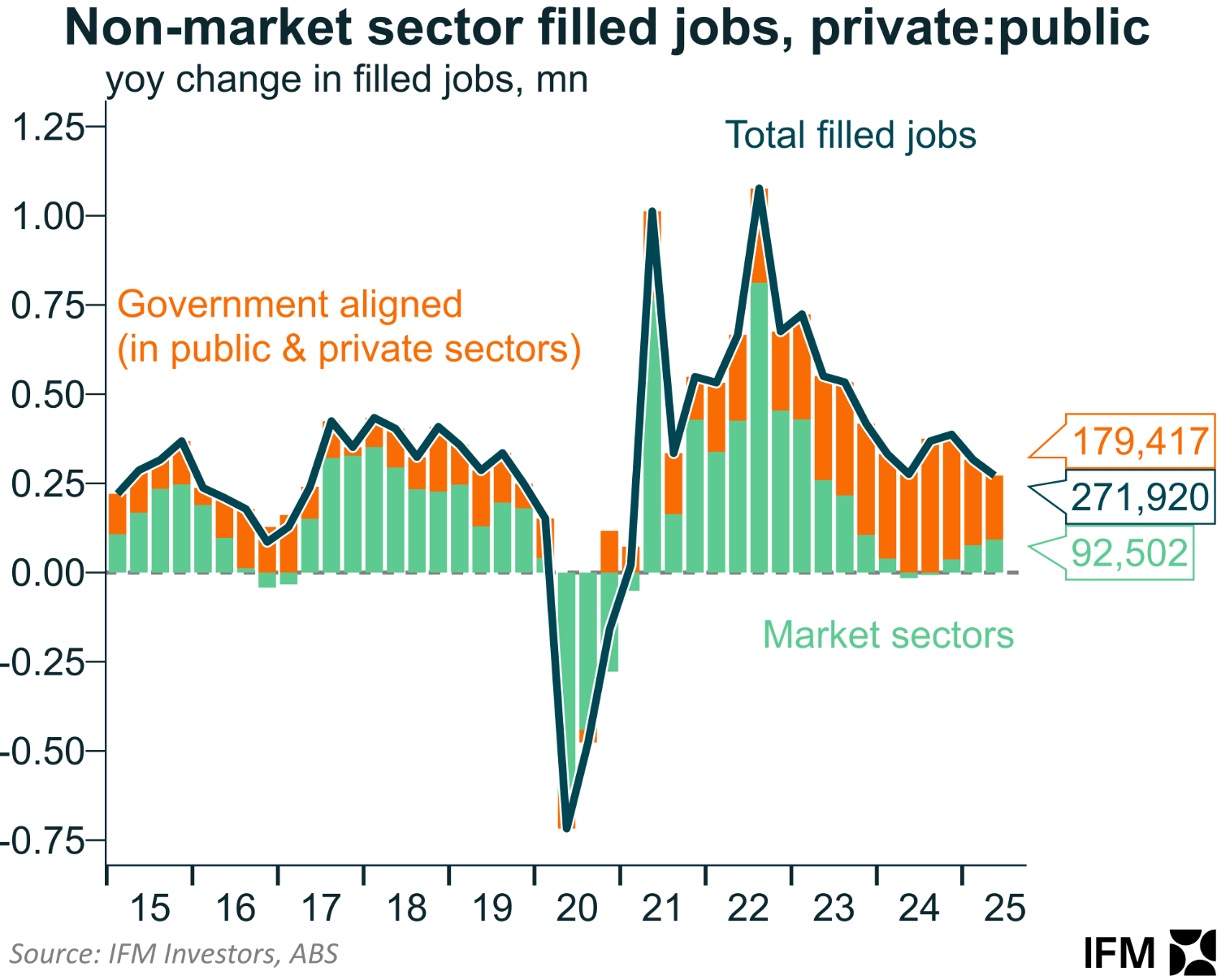

As a result, the non-market sector has dominated total job growth, despite this sector comprising only 31.5% of the nation’s jobs:

Indeed, analysis from Mark Graph suggests that Australia’s labour market is far weaker than it appears.

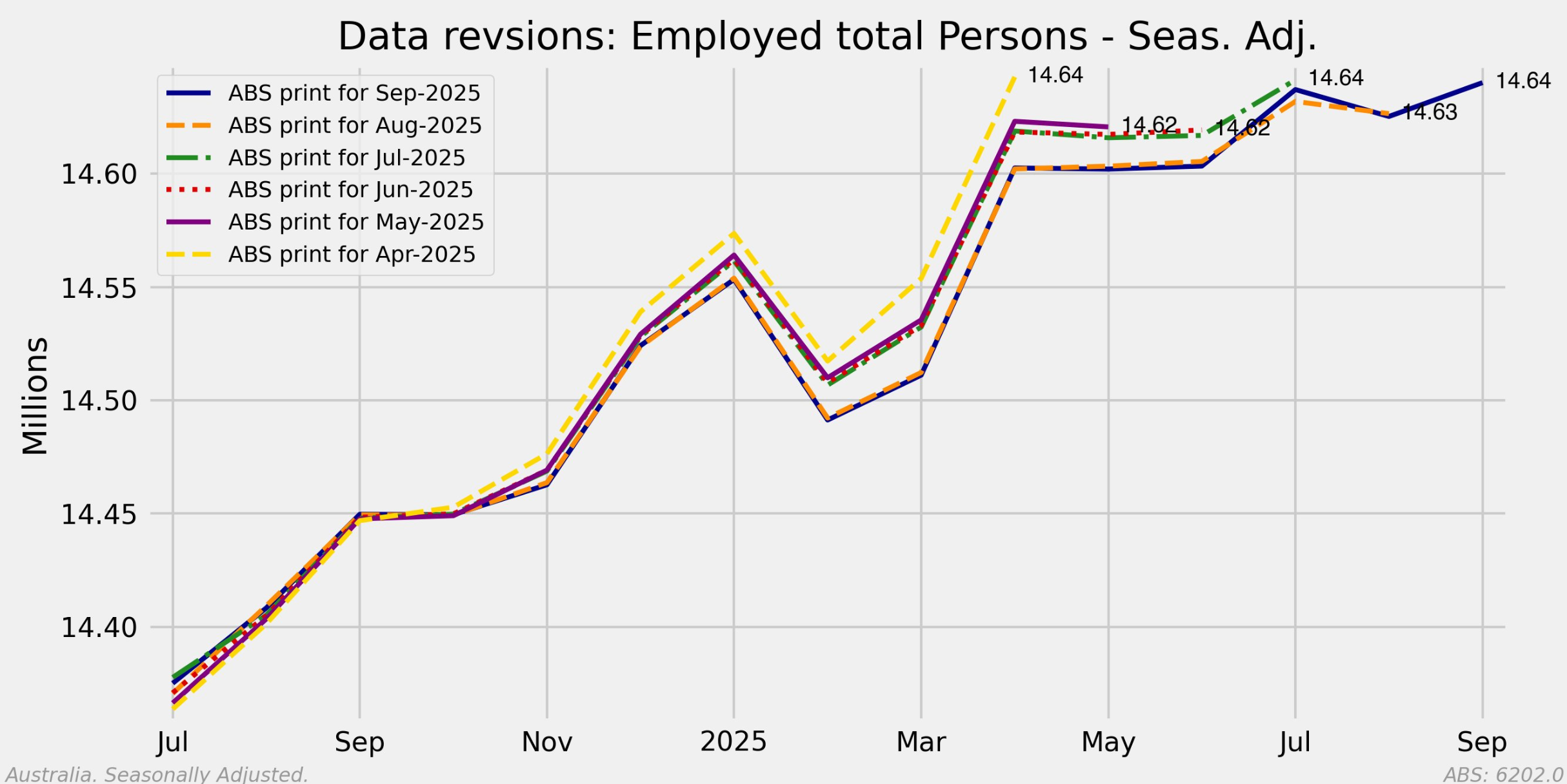

Mark Graph noted that “total employment has been printing the same for the past five months—hidden by repeated ABS revisions”:

Source: Mark Graph

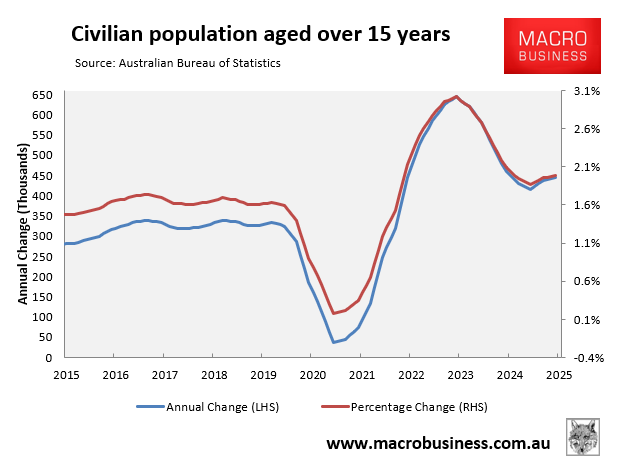

Meanwhile, there have been “plenty of new workers (mostly immigration driven)”, which “is not sustainable long term”.

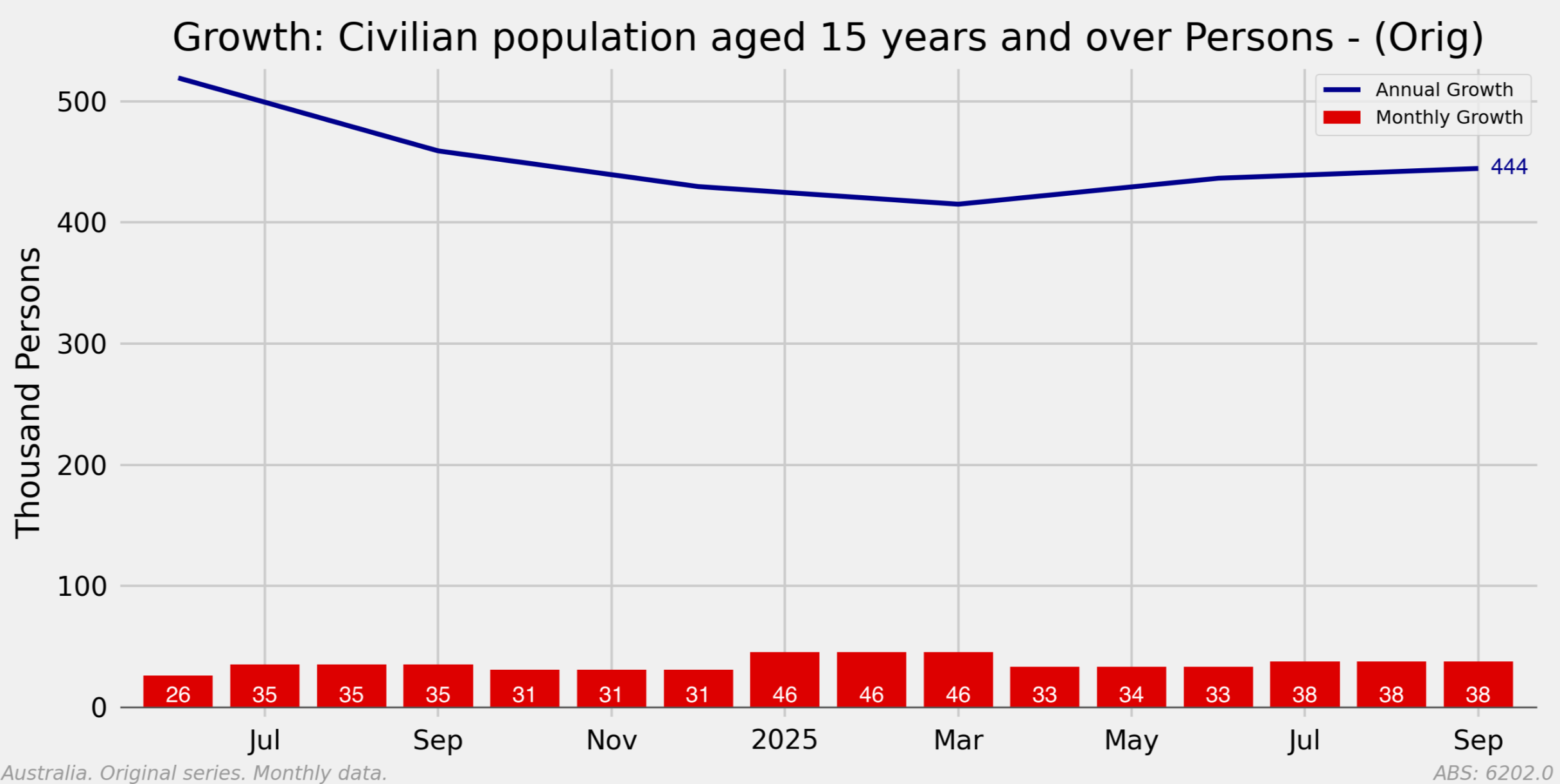

As illustrated below, Australia’s force has grown by around 35,000 per month over the past six months:

Source: Mark Graph

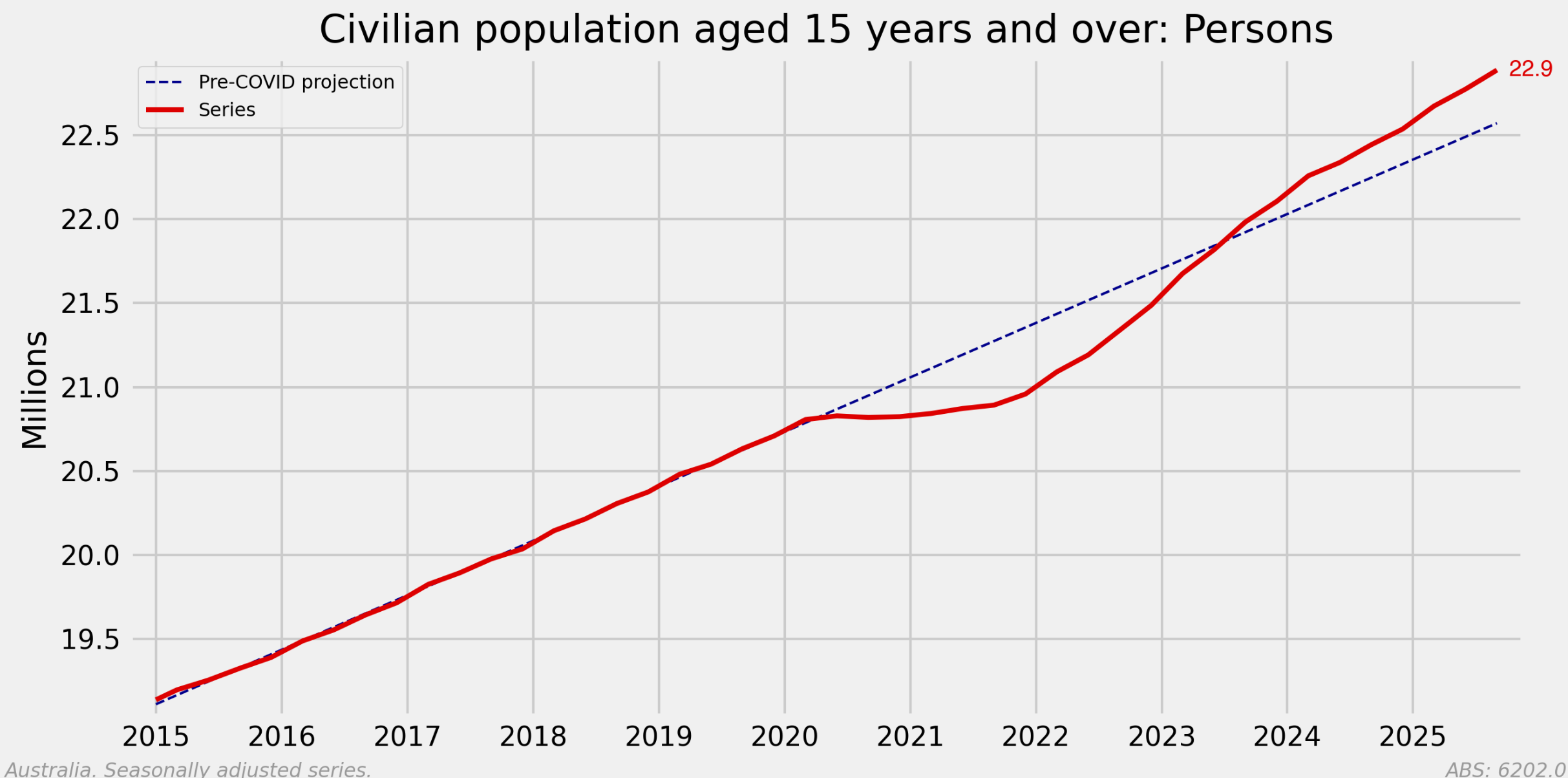

As a result, the growth of Australia’s civilian population has blown well past the pre-pandemic trend:

Source: Mark Graph

Mark Graph also showed that the market sector is badly “underperforming” on the job creation front:

Source: Mark Graph

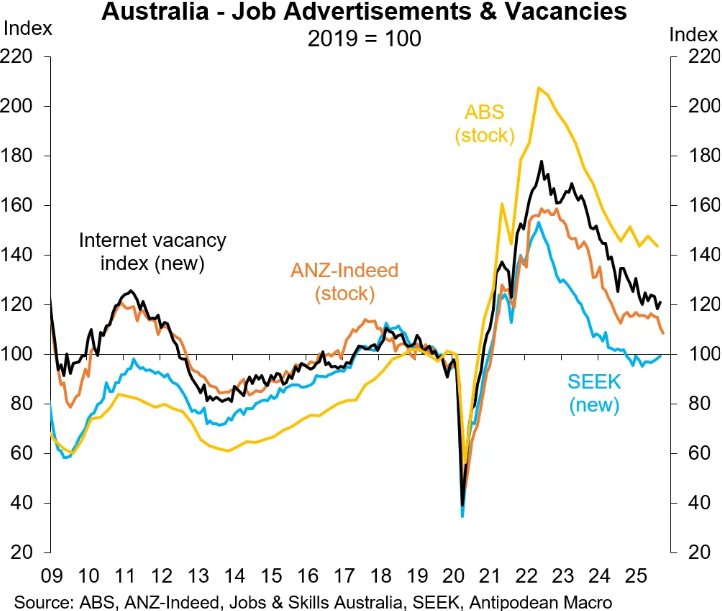

Finally, as illustrated below by Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro, all measures of job ads are falling, suggesting weaker labour demand at the same time as labour supply continues to expand aggressively:

Therefore, it is difficult to fathom how the RBA came up with its 4.4% unemployment forecast.

The labour market has been propped up by unprecedented growth in non-market jobs, which is unlikely to continue given that federal and state governments face large budget deficits and are seeking to control costs.

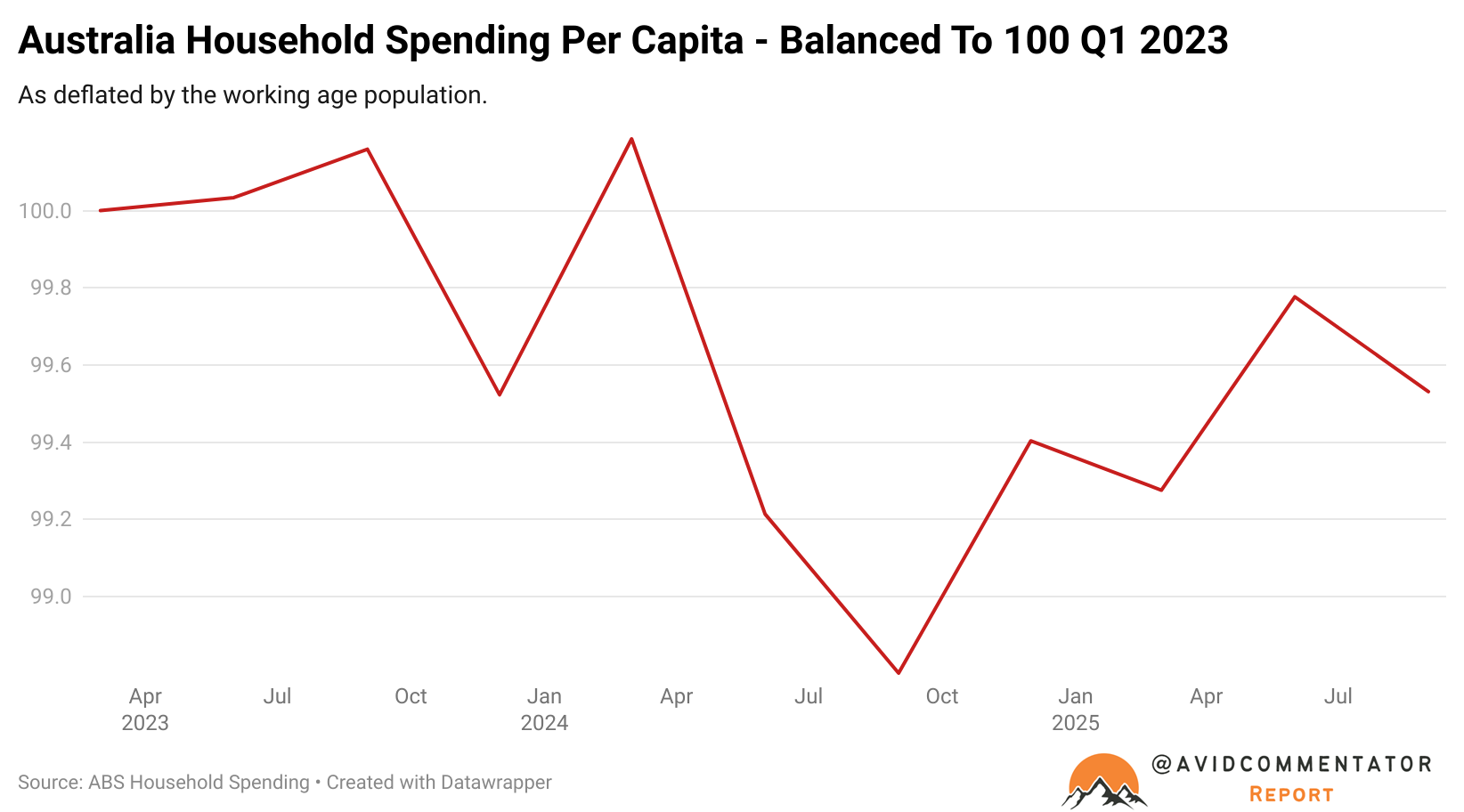

Meanwhile, the private sector economy remains soft, as evidenced by stalled household consumption spending, which is typically the largest economic driver.

Finally, labour supply continues to grow strongly via resurgent immigration.

These are the ingredients for rising unemployment, which the RBA seems to have completely misunderstood.

The upshot is that if/when unemployment does unexpectedly rise, the RBA will be prompted to cut rates.

This is why the next move in the cash rate is still likely to be down, although it is unlikely to occur before the second quarter of 2026.