Australian workers brace for higher unemployment

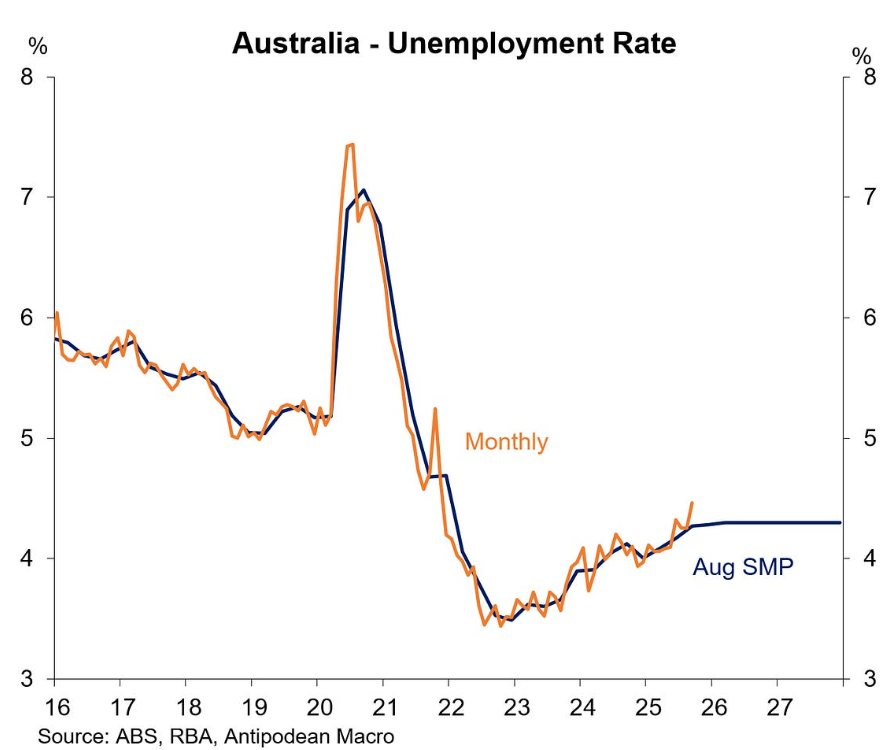

Australia’s official unemployment rate was 4.5% in September, the highest reading since November 2021 and significantly above the Reserve Bank’s forecast contained in its August Statement of Monetary Policy.

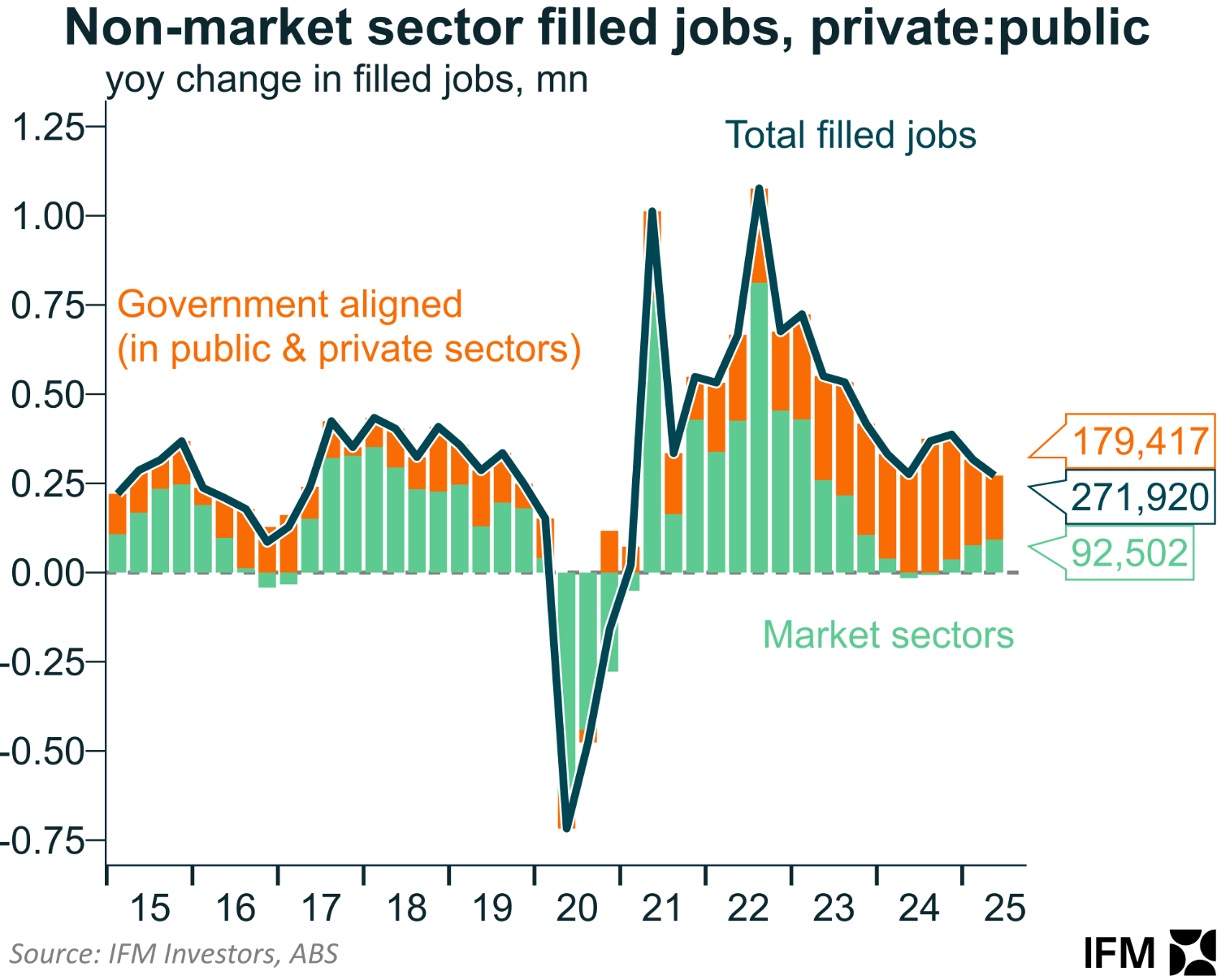

I have argued repeatedly that Australia’s labour market has been artificially propped up by the unprecedented boom in non-market sector jobs, funded by the taxpayer.

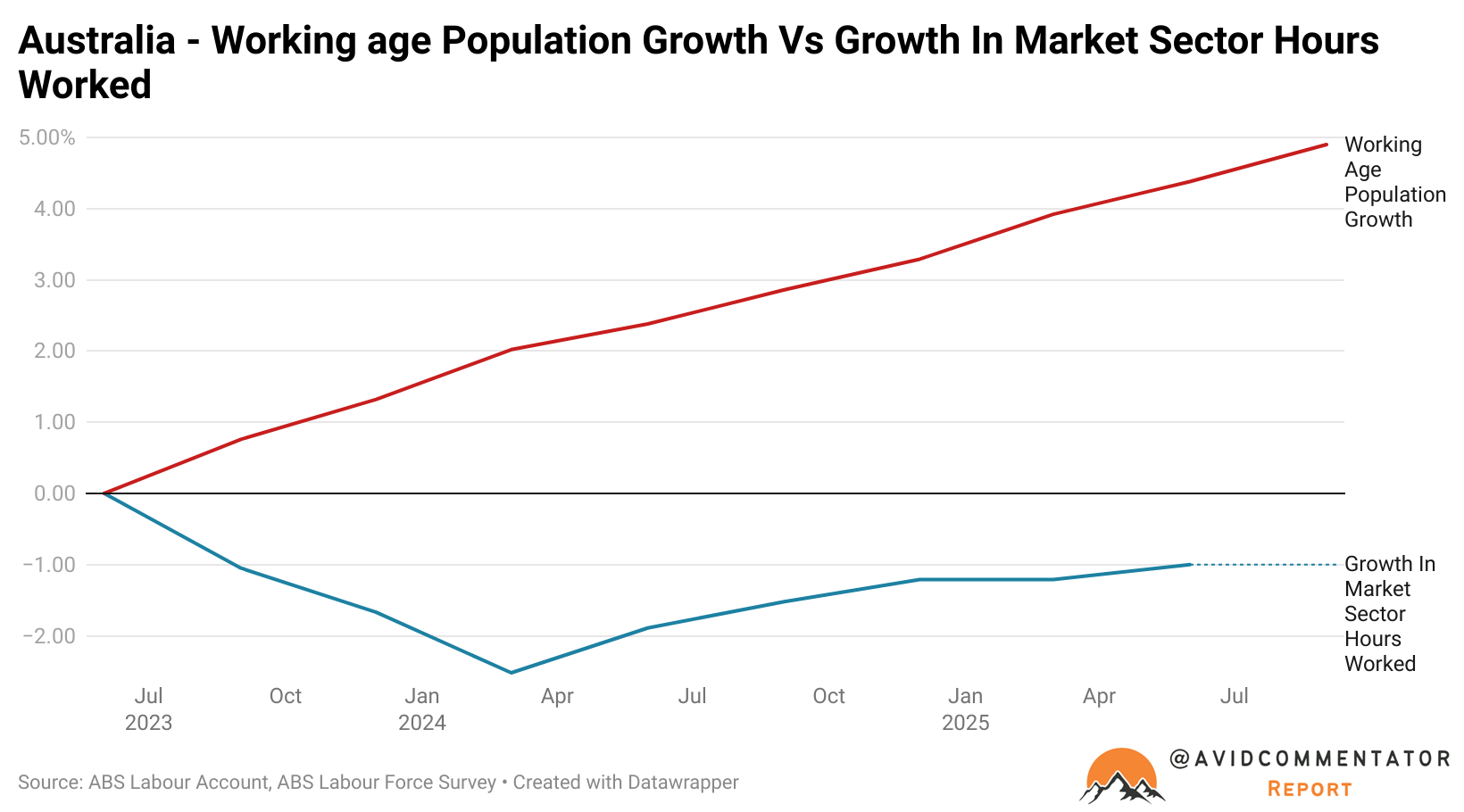

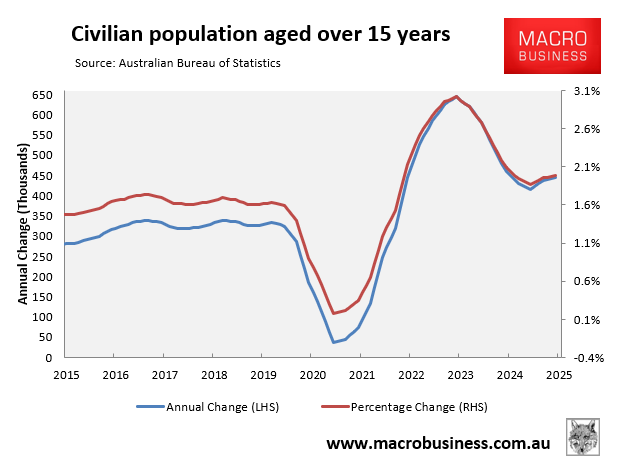

Australia’s labour force is growing by around 35,000 per month thanks to high immigration. And unless the private (market) sector can fire up, then Australia faces rising unemployment as labour supply growth outpaces demand for workers.

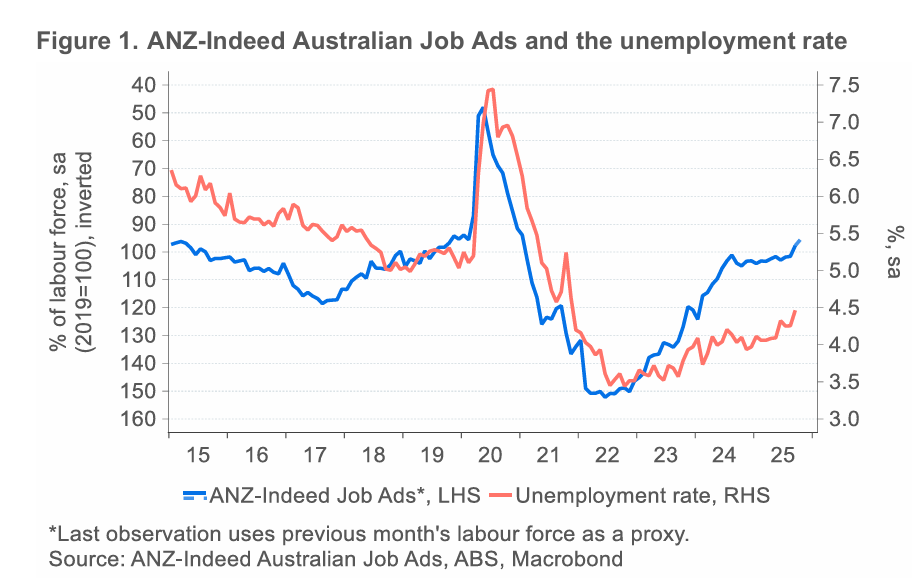

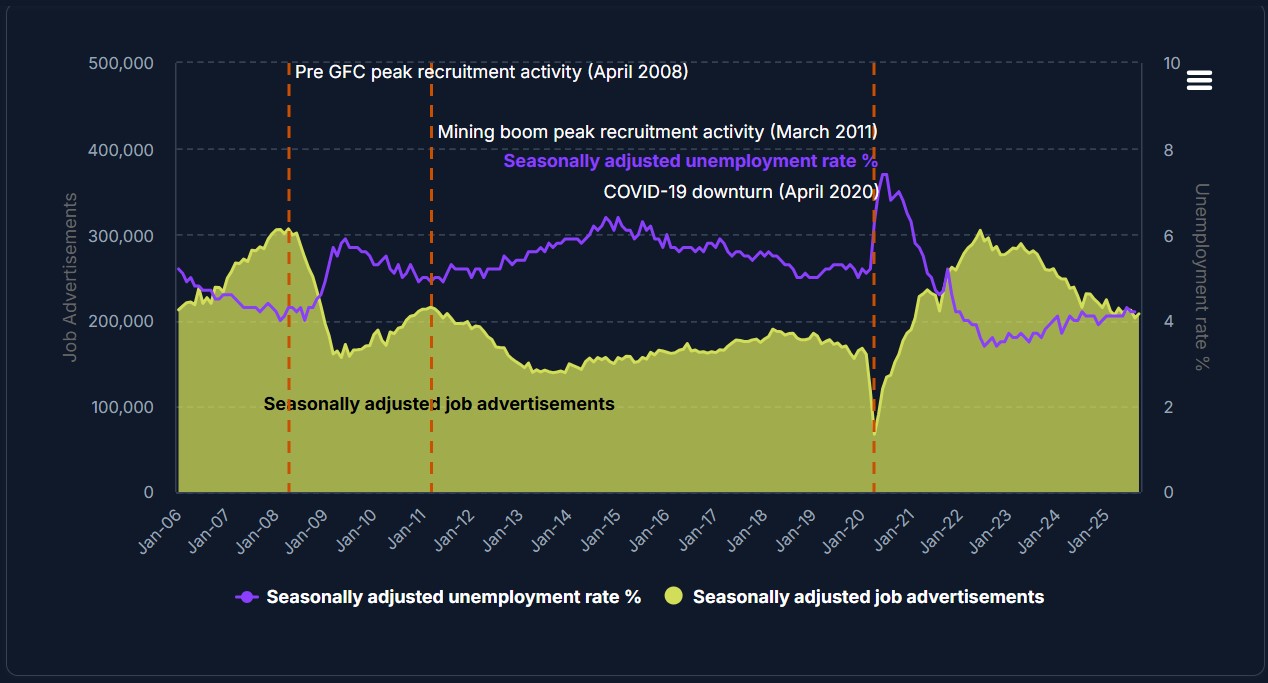

On Monday, the ANZ-Indeed Australian Job Ads survey was released, which recorded its fourth consecutive monthly decline.

In October, job ads fell by 2.2% month-on-month following a downwardly revised 3.5% month-on-month decline in September.

The following chart plots the ANZ-Indeed job ads series against the headline unemployment rate and supports the view that the labour market is softening.

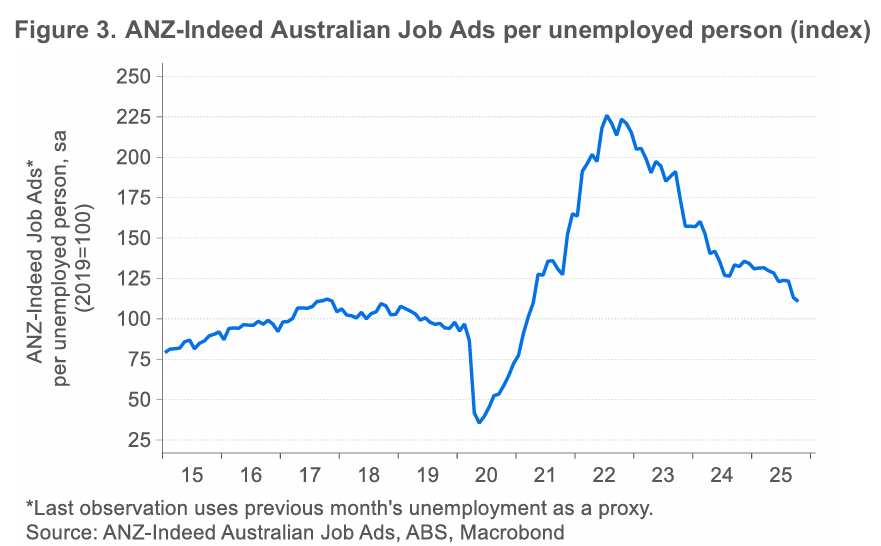

The number of job ads per unemployed person has nearly fallen back to pre-pandemic levels:

Other indicators are similar.

The JSA index is still falling

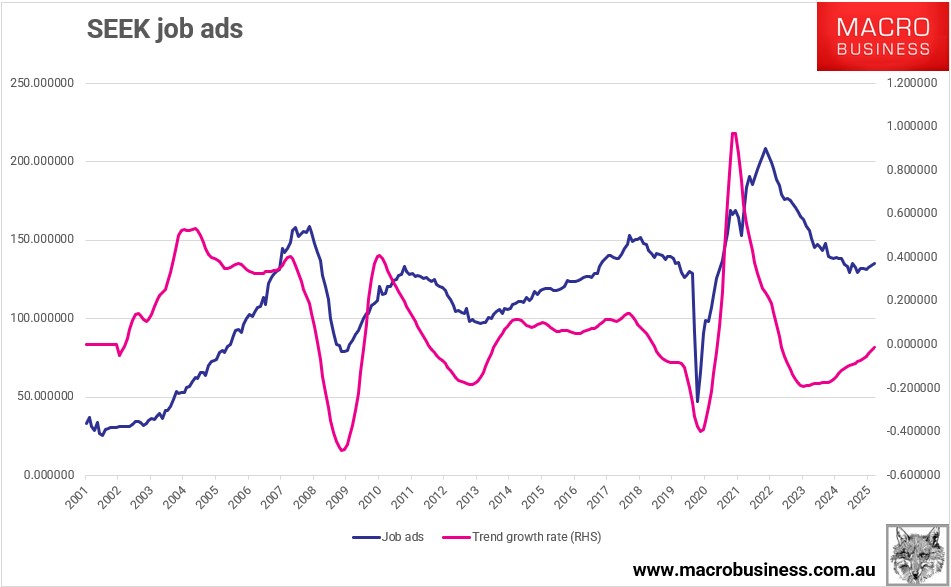

The SEEK index is a little better but is more L- or U-shaped than it is V-shaped in recovery. It also fell further and faster and is back in the 2016-2019 range.

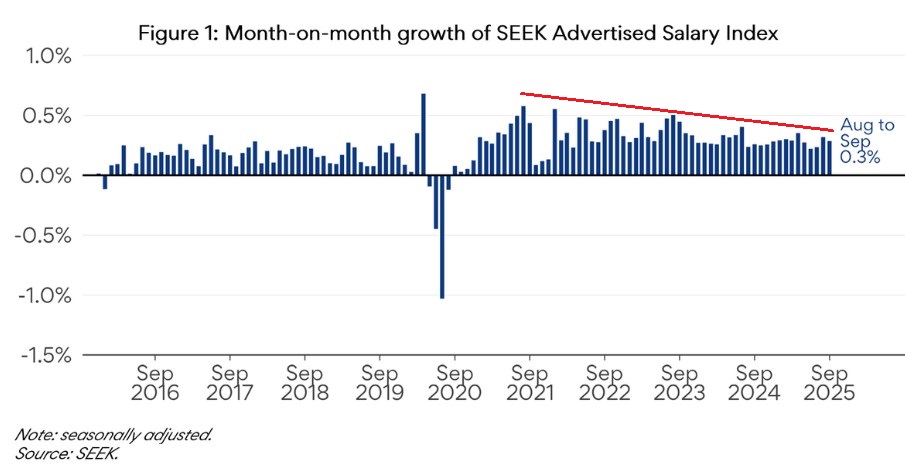

Finally, wage growth is a true litmus test of job tightness, and it is fading in trend.

Therefore, Australia’s labour market has weakened significantly, which should also moderate wage growth going forward.

The Q3 CPI shocker last week, which saw trimmed mean inflation jump by 1.0% over the quarter and by 3.0% year-on-year, has ruled out any immediate interest rate cuts.

However, there is still the prospect of further rate cuts next year if the unemployment rate rises materially.

With labour supply accelerating on the back of rebounding immigration and the market (private) sector failing to fire, a jump in the unemployment rate is a distinct possibility for 2026.

Realistically, the earliest that we could see a rate cut is the second quarter of 2026, and that would be conditional on a significant rise in the unemployment rate and inflation not getting worse.

Regardless, the Australian economy faces a prolonged period of stagflation—i.e., rising unemployment, stubborn inflation, and poor productivity/GDP growth.

The RBA will, therefore, have the unenviable task of trying to balance rising unemployment and inflation.