Australia’s ‘miracle’ jobs market has been a fool’s paradise.

The unprecedented boom in government-funded jobs has driven Australia’s job growth and historically low unemployment rate.

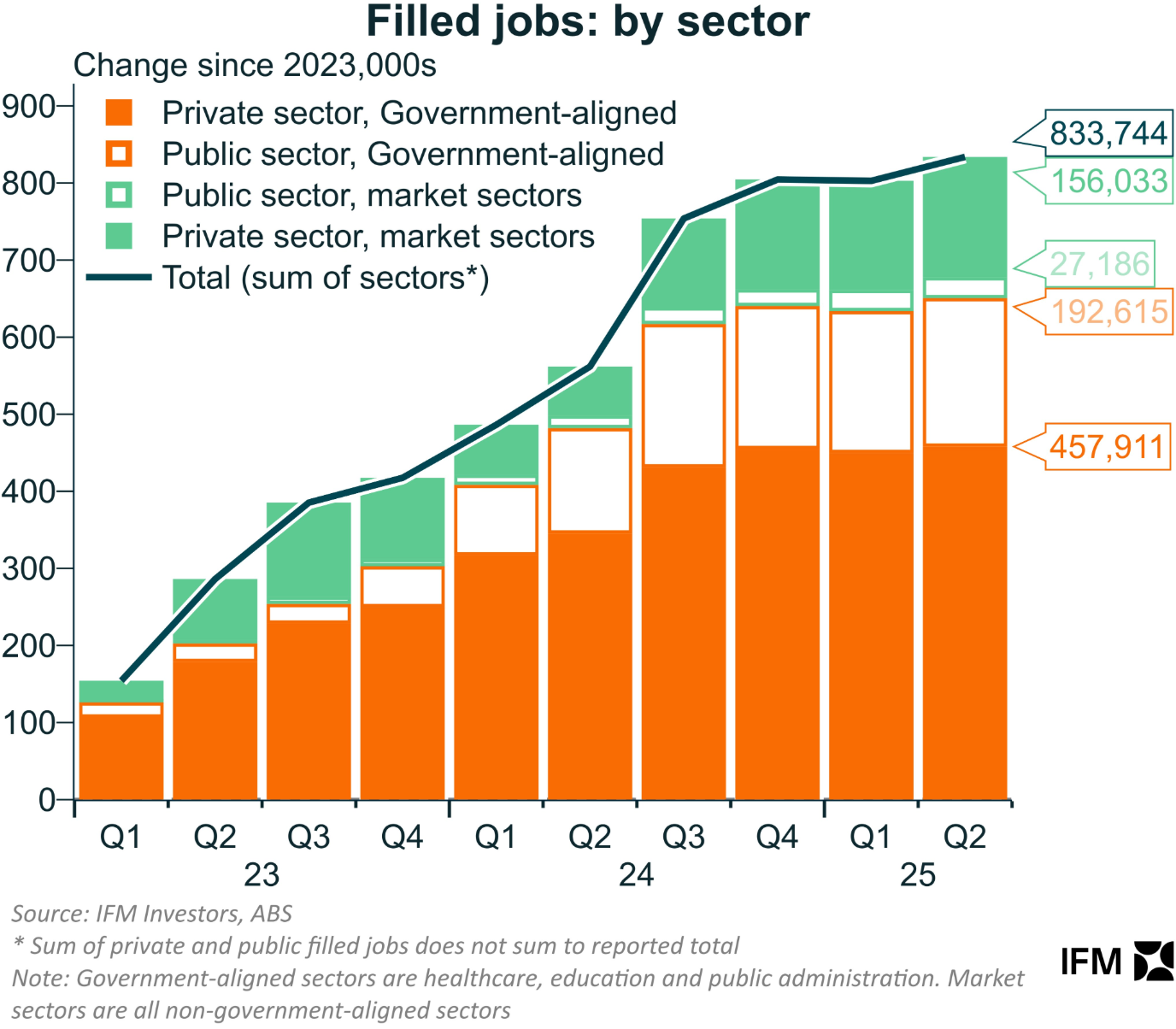

The non-market sector, comprising public and private service providers that rely on government funding, accounted for around 60% of total job creation since the pandemic and nearly 80% of job creation over the past two years.

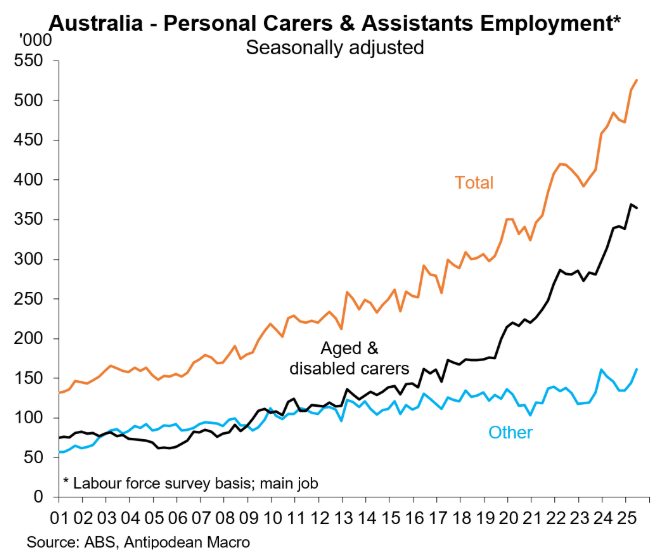

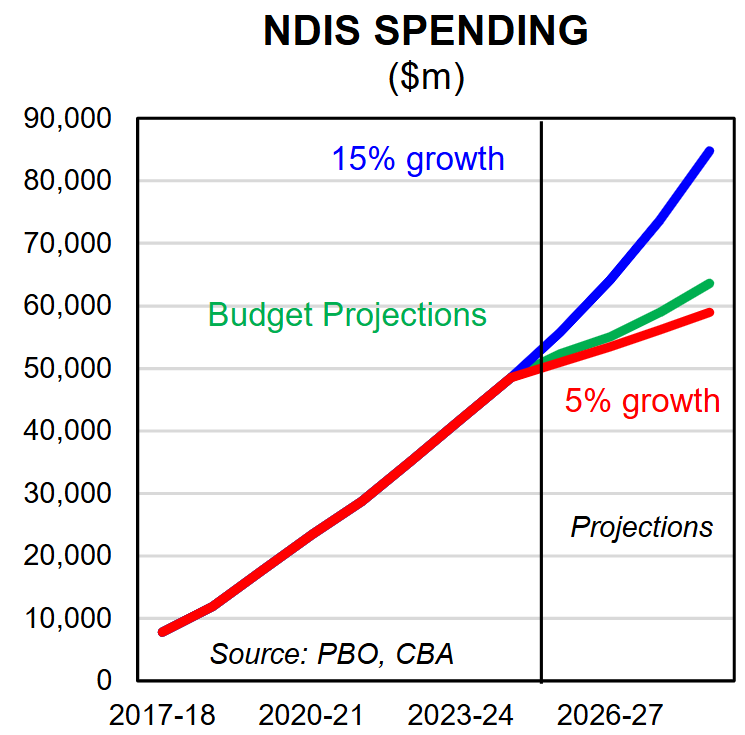

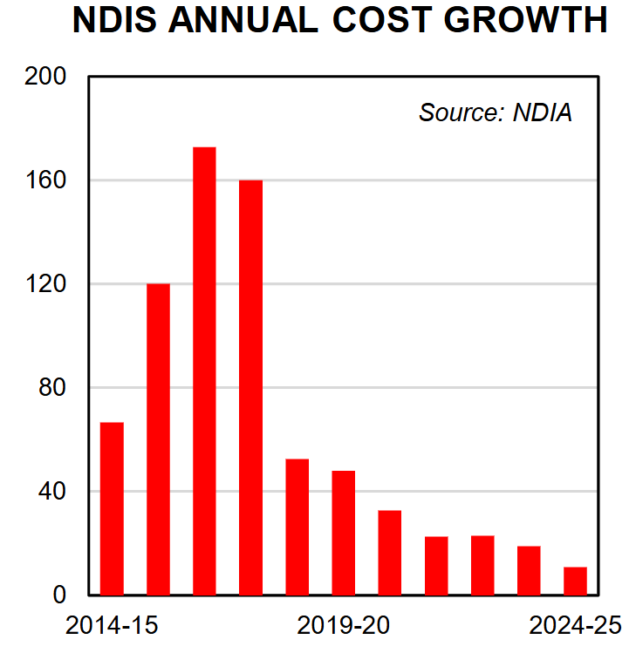

This non-market job growth has been driven by the $52 billion blowout in the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), which has fueled the growth of carer jobs.

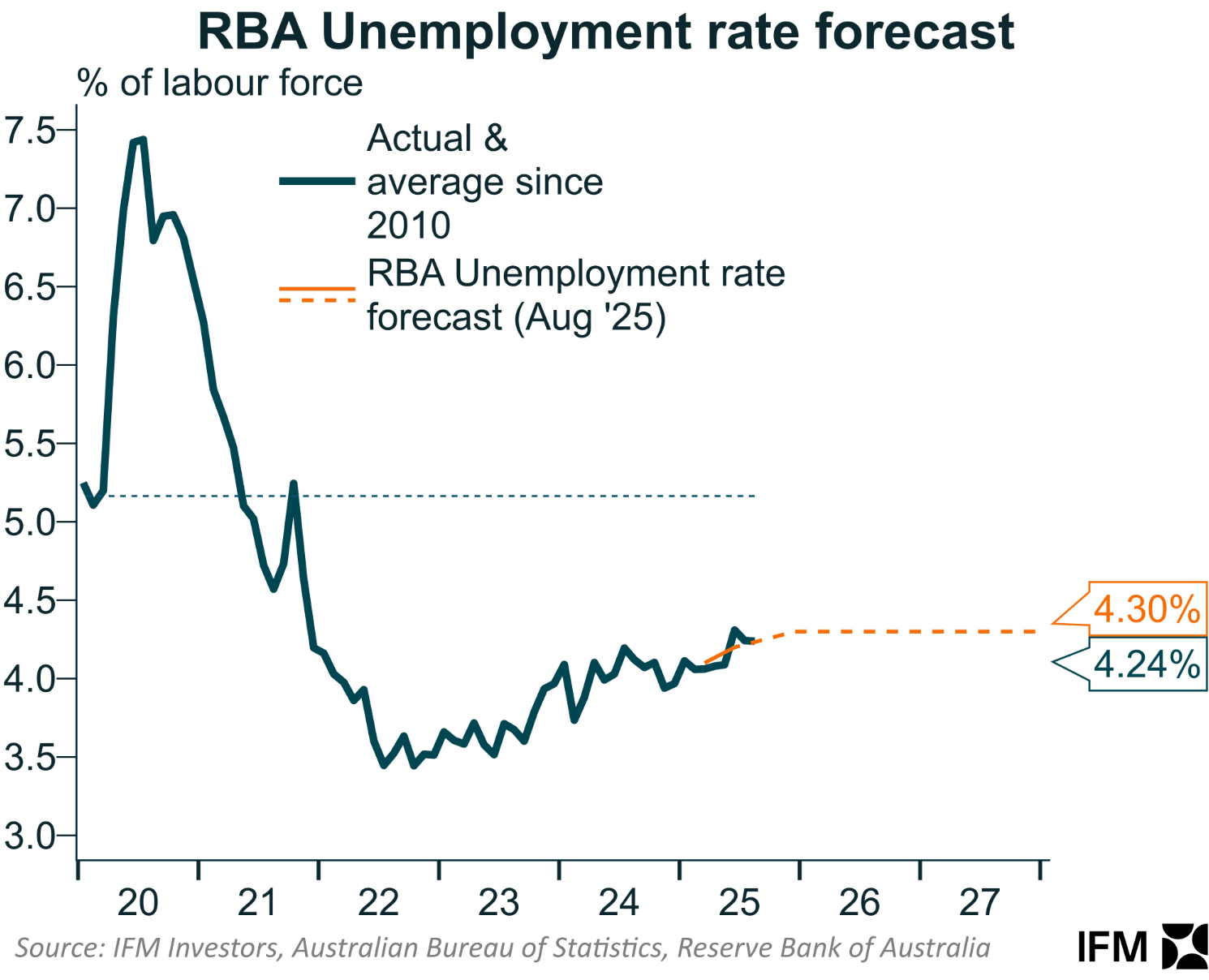

As a result, the nation’s unemployment rate remains historically low at 4.2% and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) expects unemployment to remain at this low level for the next two years.

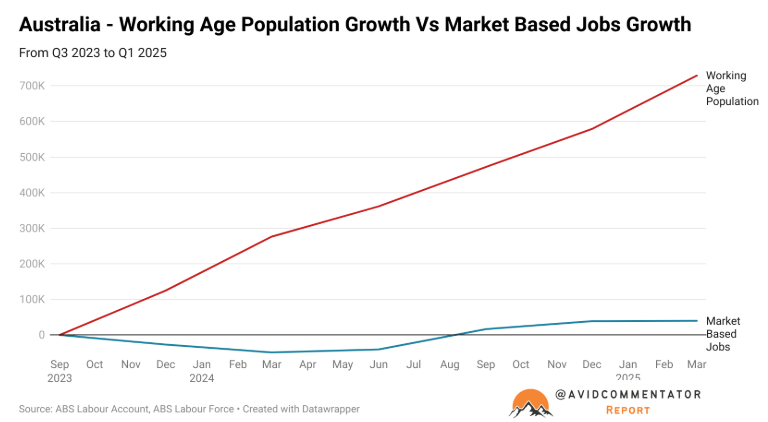

The clear and present danger is that non-market job creation stalls (or the sector loses jobs) and there is insufficient handover to the private sector.

Given the persistent strong growth in the labour force due to continually high net overseas migration, such a scenario would indicate a significant increase in unemployment.

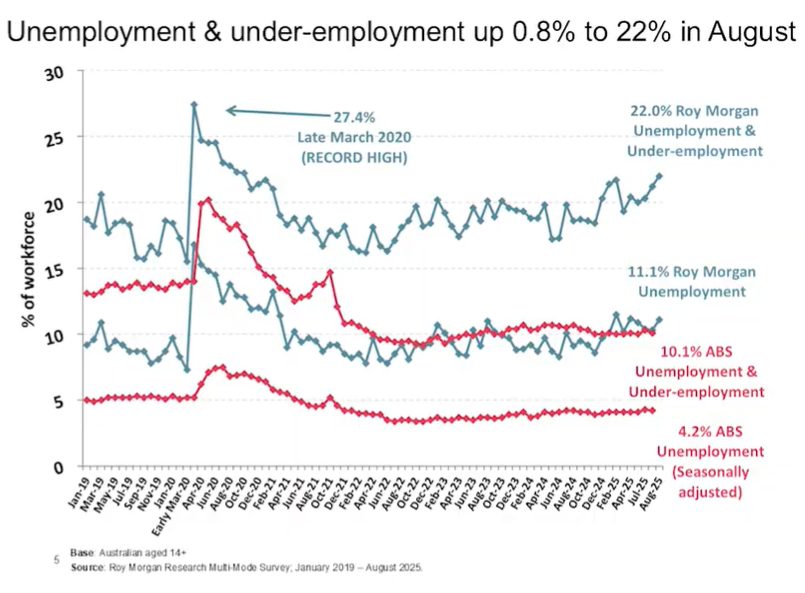

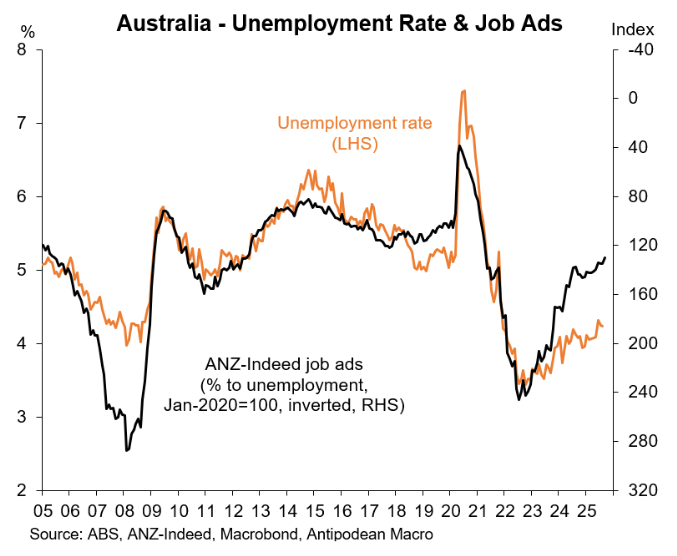

Alternative indicators of the labour market are looking shaky.

Roy Morgan’s alternative measure of unemployment and underemployment has risen sharply over the past year:

The various job ad surveys also point to rising unemployment:

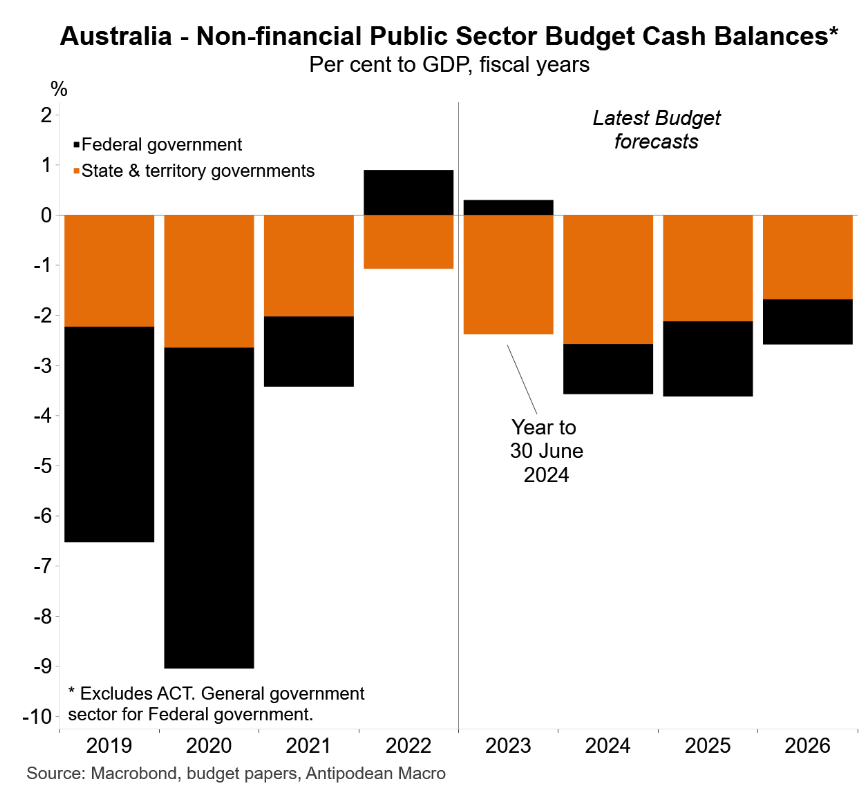

State and federal budgets are stretched, resulting in cost-cutting and austerity—neither of which is helpful for non-market employment.

For example, in its most recent state budget, the Victorian government revealed plans to reduce 2,000 to 3,000 public sector jobs, with projections indicating that the government might lay off up to 6,500 workers.

The New South Wales government recently announced that more than 1,500 jobs would be axed.

Reports indicate that federal government departments are confronting “funding cliffs” that could lead to the loss of thousands of jobs.

For example, the Health Department’s budget is expected to decrease from $1.69 billion in 2024-25 to $893 million in 2027-28, while the Energy Department’s funding is expected to shrink from $357 million in 2025-26 to $180 million in 2028-29.

The most severe budget gaps are expected to occur between 2026 and 2027, when financing for up to 100 programs will expire.

The federal government is also under tremendous pressure to reduce the cost of the NDIS, which has been the primary driver of the large increase in non-market employment.

Australia’s non-market job boom, therefore, appears to have ended amid nascent austerity measures.

With Australia’s private sector failing to fire up and the government continuing to import hundreds of thousands of migrant workers each year, there is a real possibility that the country’s unemployment rate rises well beyond the RBA’s forecast.

Unemployment is the single biggest downside risk for Australian interest rates.