Australians are consistently ranked among the wealthiest people on earth.

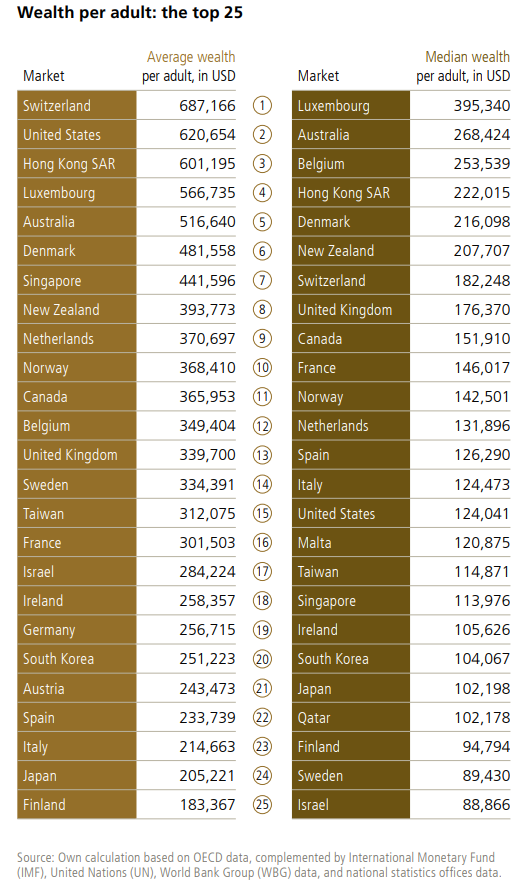

The 2025 UBS Global Wealth Report ranked Australians second in the world for median wealth, with the typical Australian having a net worth of US$268,424.

Australia had 1,904 US dollar millionaires in 2025, according to UBS.

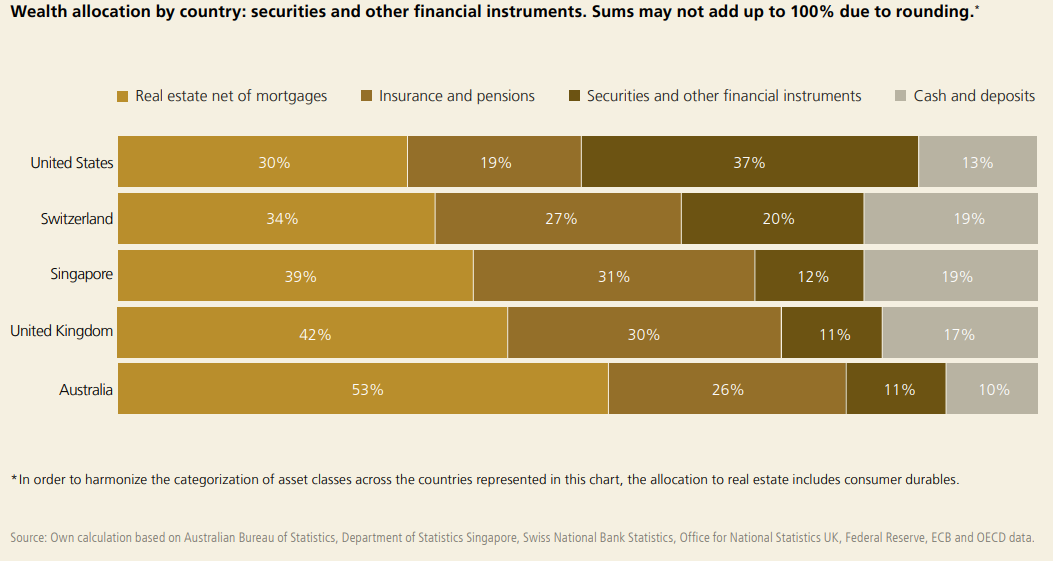

However, Australia stands out from most other nations, as it stores more than half of its household wealth in illiquid residential property.

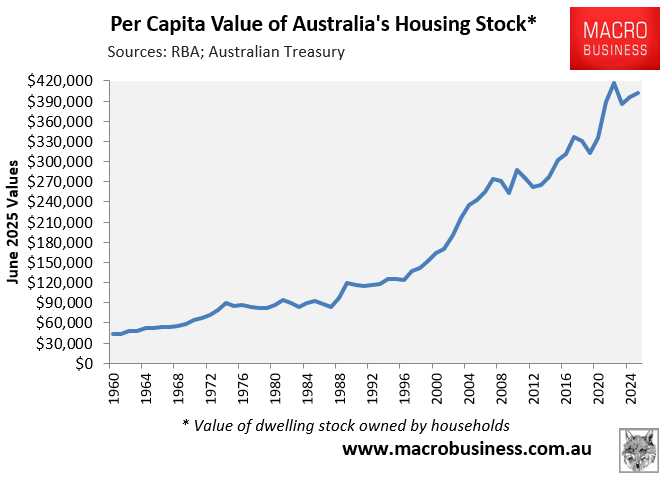

ABS data shows that as of Q2 2025, Australia’s housing stock was valued at $401,850 per person in real terms, and it had more than tripled over 30 years:

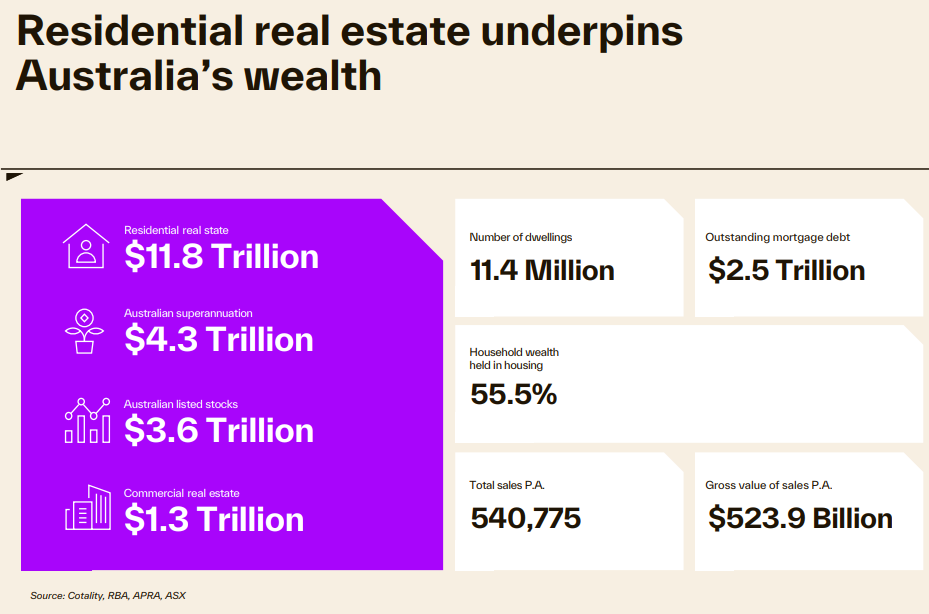

On Wednesday, Cotality released its October housing market chart pack, which reported that the value of Australia’s residential housing stock has surged to $11.8 trillion spread across 11.4 million dwellings.

As a result, the average dwelling in Australia is now valued at an extraordinary $1,035.000:

Dividing $11.8 trillion by Australia’s current population of 27,779,992, as per the ABS Population Clock, gives a per capita housing value of $424,766.

As noted above by Cotality, the share of Australian household wealth stands at 55.5%, even higher than estimated by UBS.

Cotality’s Head of Research for Australia, Eliza Owen, commented:

“This $11.8 trillion milestone is a clear testament to the resilience of Australia’s property market, where national dwelling values are now up 4.8% over the past year”.

“We’re seeing a clear building of momentum, with a 2.2% rise over the September quarter alone, the largest quarterly increase since May 2024”.

“At the moment, there’s some uncertainty around the timing of another cash rate reduction, and inflation impacting market momentum through to the end of the year”.

“However, if the property market were to continue at its current rate of growth, it’s possible the combined market value could hit $12 trillion by the end of the year”.

Therefore, if Australian dwelling values surge to $12 trillion or beyond, then Australians will become even richer! It’s like a perpetual motion machine.

Let’s be real: most of Australia’s household wealth is fake.

Higher property values offer little benefit for owner-occupier households, which only need a place to live.

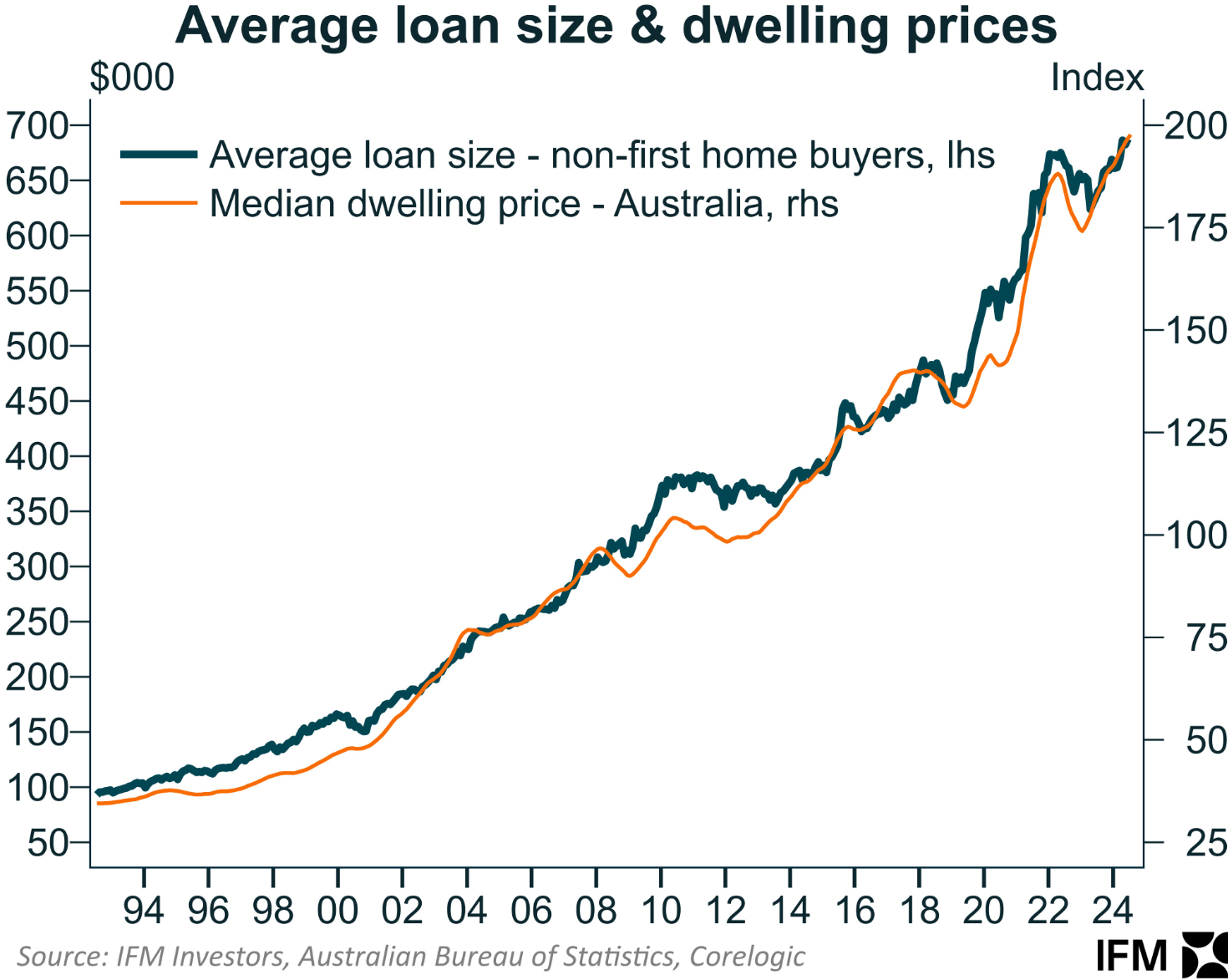

Debt is suffocating Australians as they take on ever-larger mortgages to cover rising housing costs.

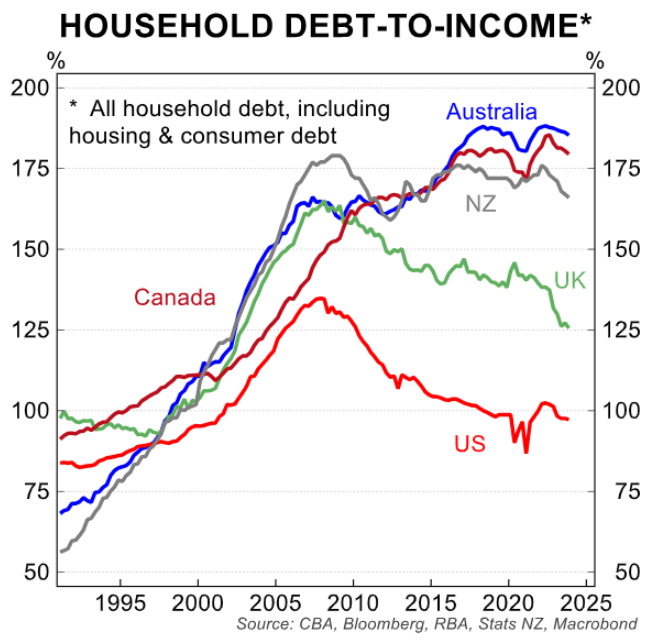

As a result, Australian households have some of the world’s highest debt levels.

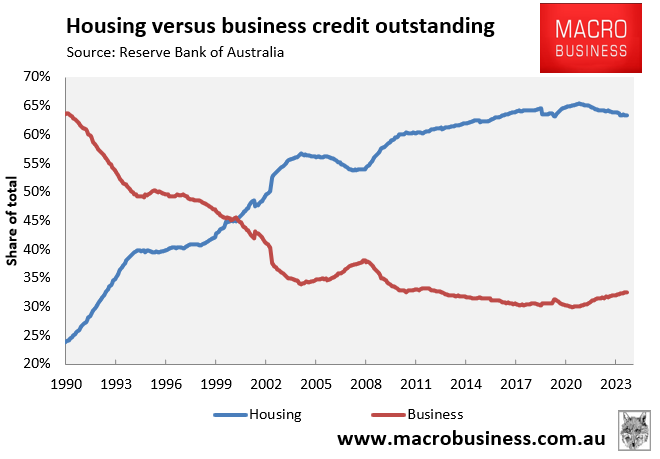

Australia’s banks have also grown into enormous building societies that favour residential housing loans over productive lending to businesses.

In 1990, companies accounted for almost two-thirds of all bank loans, while mortgages accounted for only about a quarter.

Thirty-five years later, the ratio has flipped, with almost two-thirds of bank loans for housing and only one-third for business.

If Australians are so wealthy, how come so many people are hurting financially? The truth is that Australia would be a wealthier and more productive nation with lower property costs.

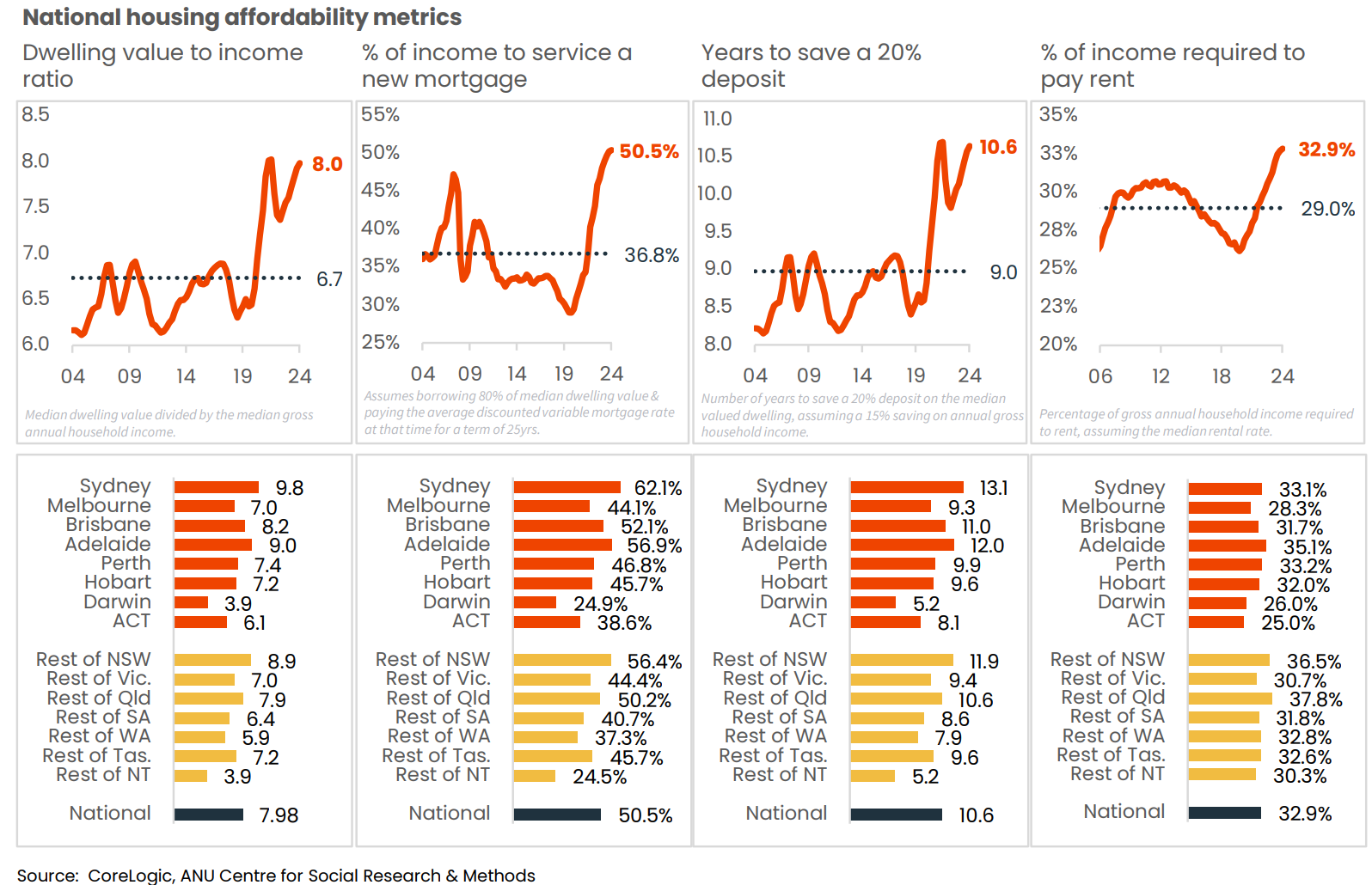

Mortgage and rent payments, which, according to Cotality, accounted for an unprecedented amount of income at the end of 2024, are straining many households.

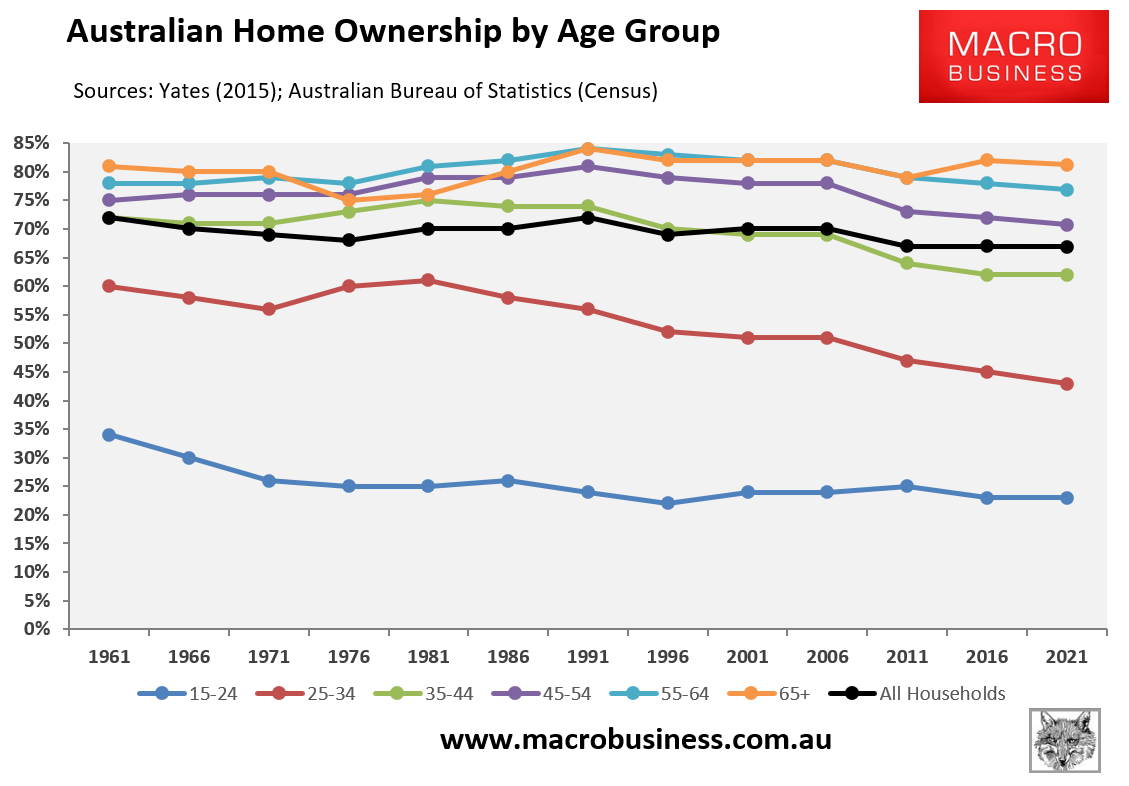

Given that housing affordability is at an all-time low and our younger generations are unable to purchase a home without parental financial aid or government subsidies, how can Australian households be regarded as the world’s second wealthiest?

Australians would be wealthier if the average home were worth $500,000 instead of more than $1 million, and household debt was 90% of income rather than 180%.

Australia would be a far more equal nation, and residents would be financially better off, if homes cost half as much as they do now, with half the debt.

According to the 1991 Census, Australia’s homeownership rate was about 5% higher than it is now. Homes cost roughly three times income (compared to eight times today), and household debt was 70% of income, compared to 180% today.

Banks also lent about two-thirds to businesses and one-quarter to mortgages.

Despite having significantly less property wealth, Australian households were financially better in 1991 than they are today. The Australian economy was likewise far more balanced, diverse, and productive in 1991 than it is today.

Australia’s high housing costs have a significant detrimental impact on younger and future generations, who are forced to pay significantly more for housing than they woA home, regardless of whether it costs $500,000 or $2 million, serves the same purpose: to provide shelter.

Most people don’t care about growing their “wealth” in homes.

Finally, Australia’s $11.8 trillion housing market represents a massive misallocation of resources that has hurt productivity, equity, and the overall economy.

The Australian economy would be more balanced and productive if capital was directed towards supporting innovation and capital deepening rather than raising housing prices.