Abul Rizvi’s forecast that Australia’s net overseas migration (NOM) will track around 300,000 under current immigration policies, 15% higher than the Treasury’s forecast, confirms that the rental crisis will persist.

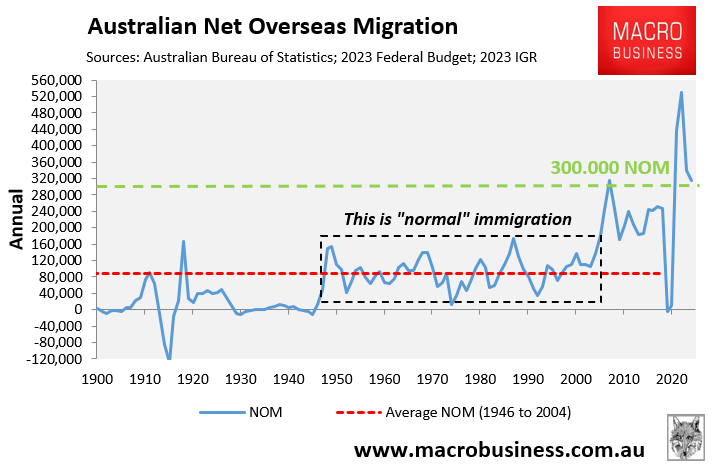

It is important to put Rizvi’s 300,000 NOM forecast into a historical perspective.

In the first 60 years following World War II, Australia’s NOM averaged 90,000 per year, with only two years exceeding 150,000.

In the 15 years of ‘Big Australia’ immigration preceding the pandemic, NOM averaged 220,000 per year, a 145% increase over the post-war norm.

With the pandemic border closure included, NOM averaged 270,000 over the 5.25 years ending in Q1 2025, a 200% increase over the post-war average.

Rizvi’s 300,000 NOM forecast would represent a 233% increase on the post-war average.

In fact, prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, Australia only exceeded 300,000 NOM once in history—i.e., 2008-09 (315,700 under Rudd).

The impact on the rental market from such extreme immigration would truly be devastating.

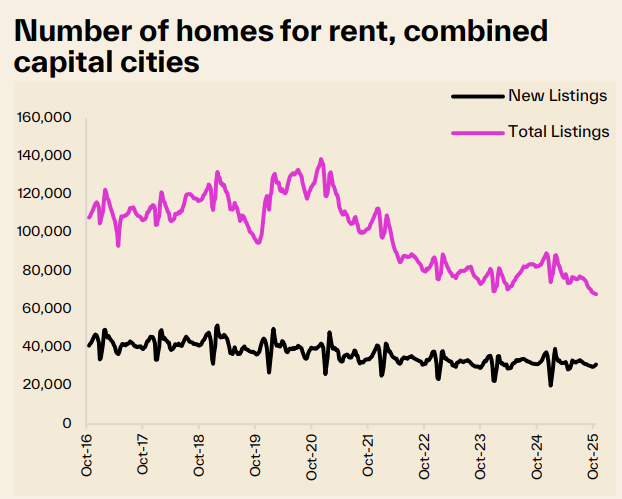

Already, the number of homes listed for rent across the combined capital cities is at a record low, as are rental vacancy rates, according to Cotality:

Source: Cotality

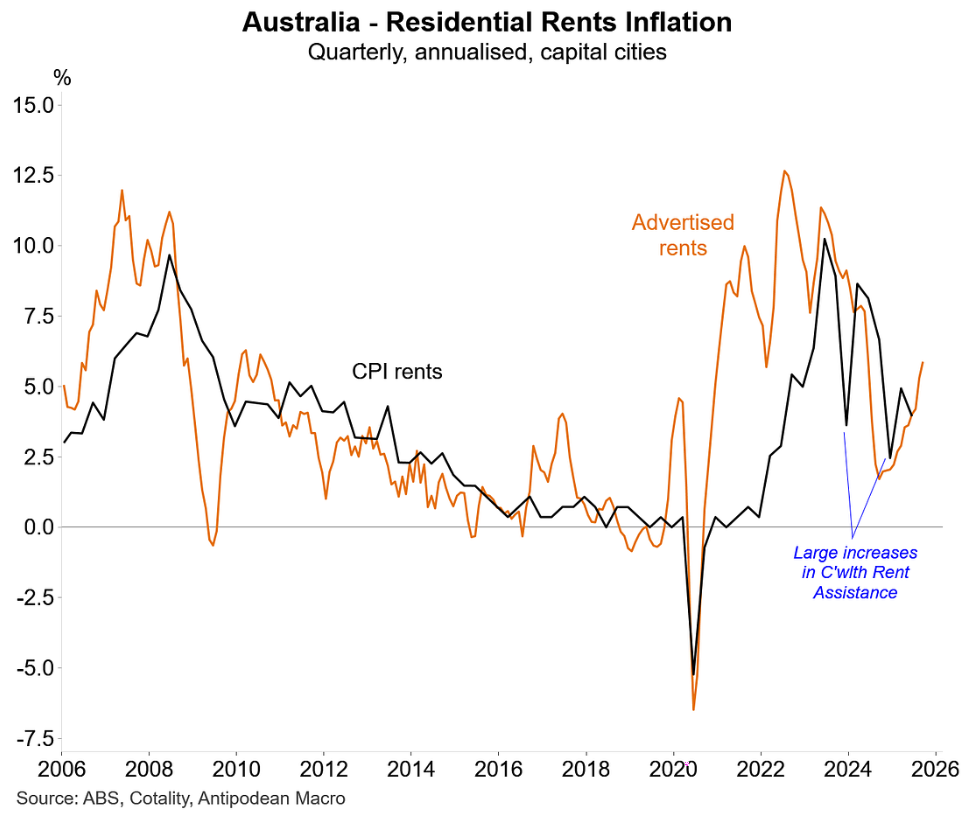

Asking rents are beginning to surge once more, which follows a 43.8% increase over the previous five years, which has added nearly $10,500 to the median tenants’ annual rental bill, according to Cotality:

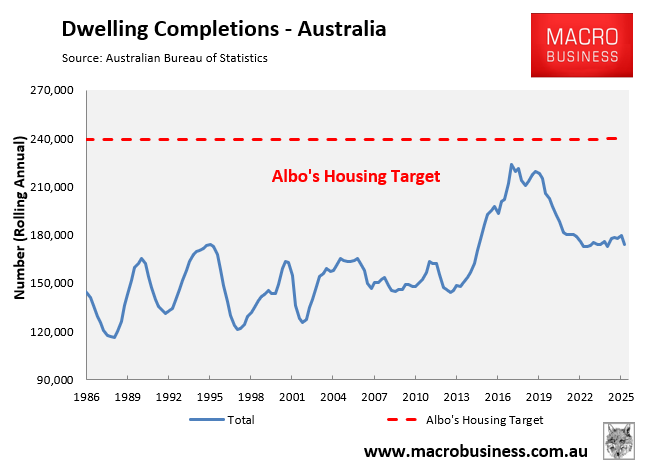

Meanwhile, actual housing construction is bottlenecked, with the number of dwelling completions nationally falling by 2% in 2024-25, tracking 65,970 (27%) below the Albanese government’s housing construction target:

Make no mistake, the Albanese government was forewarned that Australia’s rental crisis would worsen unless immigration was reduced.

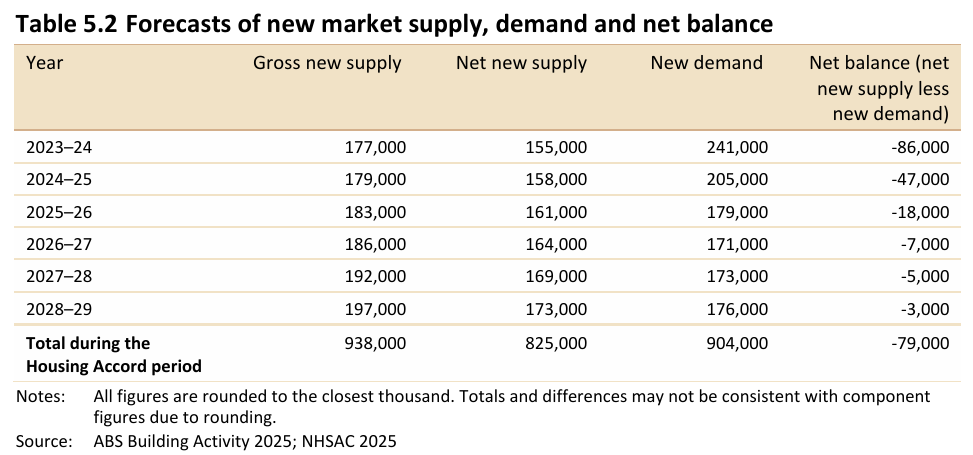

The National Housing Supply and Affordability Council’s (NHSAC) latest State of the Housing System report, released in May, forecast that new housing supply would remain below population demand over the entire five-year National Housing Accord period to 2028–29, resulting in an additional cumulative undersupply of 79,000 homes.

However, NHSAC’s 79,000 shortage projection is conservative, given it is based on the Centre for Population’s NOM forecasts, which project a reduction in NOM to 255,000 per year in 2025–26 and subsequently to 225,000 throughout the remaining forecast period.

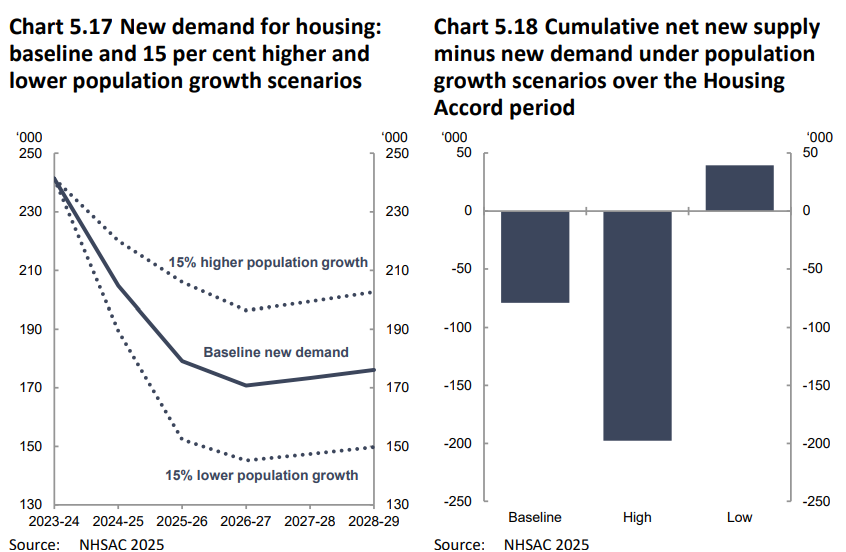

NHAS warned that if Australia’s population grows 15% faster than projected, as suggested it will by Abul Rizvi, then Australia’s housing shortage will increase to around 200,000 over five years:

Conversely, NSAC projected a surplus of 40,000 homes after five years if population growth is just 15% less than forecast by the Centre for Population.

The only silver lining is that the rental market is ultimately pegged to wage growth, which should prevent rents from rising too far above incomes.

However, while rental growth may top out, it will come at the expense of more group housing and homelessness.

Thus, the rental market may have an affordability ceiling, but not a misery ceiling.

In the lead-up to the 2022 and 2025 federal elections, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese stated that Labor would run a smaller and less temporary migration program.

Instead, Labor has delivered a larger, lower-quality, and more temporary migration program than ever before.

As population demand continues to outstrip supply, Australian renters will bear the consequences.