Late last week, The AFR published two articles by the same author on the same day that neatly encapsulated Australia’s housing farce.

First, reporter Luke Kinsella noted that all states were falling short of their agreed National Housing Accord targets, which nationally “fell 66,000 homes short of the 240,000 required to keep pace with the goal”.

Not even an hour later, Kinsella reported that the Albanese government will likely overshoot its immigration projections by 15%:

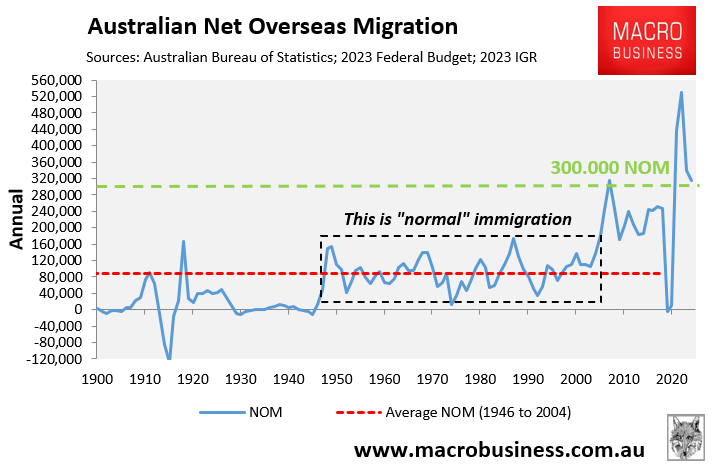

The 15% estimate is based on analysis from former senior immigration department bureacrat Abul Rizvi, who suggested that net overseas migration (NOM) would likely average around 300,000 annually going forward.

“Going forward, net overseas migration will be probably around 300,000 under current policy settings”, Rizvi warned.

“The government’s processing of student visas is set to ramp up again, and the huge backlog in permanent visa applications will have to be accommodated eventually”.

Rizvi’s 300,000 NOM forecast is extreme. Before the pandemic, Australia had only exceeded 300,000 NOM once in history—i.e., 2008-09 (315,700 under Rudd).

The above articles by Kinsella highlight how the discourse on Australia’s housing crisis is trapped in a vicious cycle.

The Albanese Labor government has continually overshot its migration forecasts, resulting in a worsening shortage of homes. Then policymakers and the media continue to blame a ‘lack of supply’ rather than excessive immigration demand. Rinse and repeat.

Meanwhile, the actual forecasts from the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council (NHSAC) continue to be ignored.

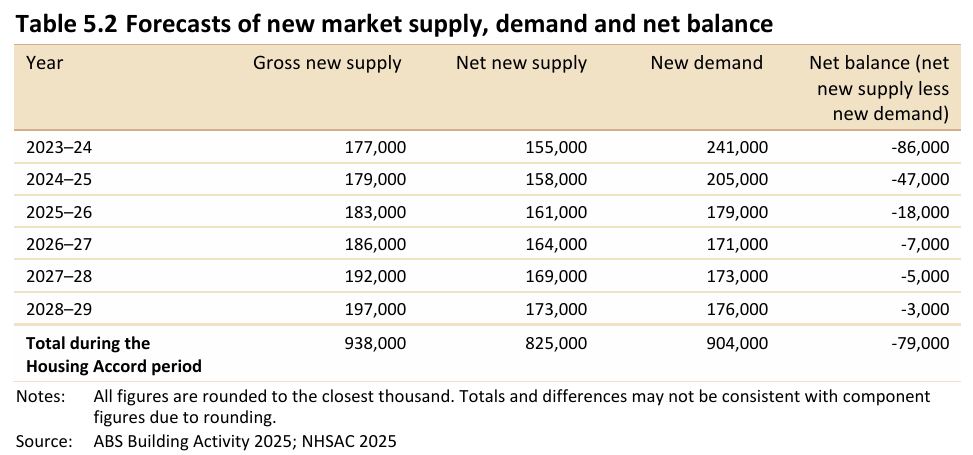

NHSAC’s latest State of the Housing Market report forecast that new housing supply would remain below population demand over the five-year National Housing Accord period to 2028–29, resulting in an additional cumulative undersupply of 79,000 homes.

However, NHSAC’s 79,000 shortage projection is conservative, given it is based on the Center for Population’s NOM forecasts, which project a reduction in NOM to 255,000 per year in 2025–26 and subsequently to 225,000 throughout the remaining forecast period.

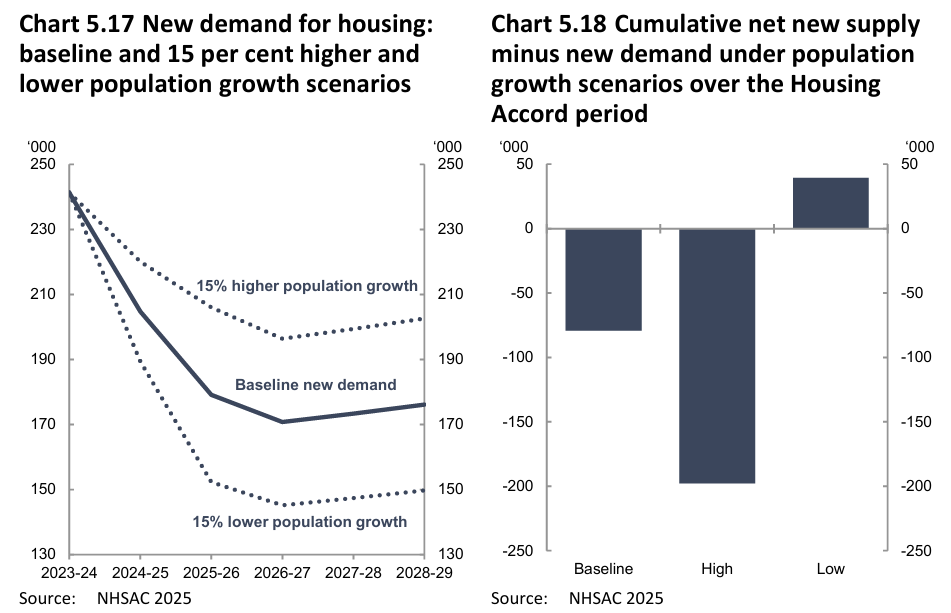

If Australia’s population grows 15% faster than projected, as suggested by Abul Rizvi, then NHSAC forecasts that Australia’s housing shortage will increase to around 200,000 over five years:

s

Conversely, NSAC’s sensitivity analysis projected a surplus of 40,000 homes after five years if population growth is just 15% less than forecast by the Center for Population.

Based on NHSAC’s modelling, cutting NOM to a level compatible with supply is the only genuine solution to Australia’s housing shortage.

Sadly, the Albanese government has chosen to double down on a larger migration program, which will inevitably make Australia’s housing shortage far worse.

It is time that the Australian media held the government to account rather than focusing on the supply fallacy.