Last week, Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) governor Michele Bullock was grilled by Greens senator Nick McKim about the RBA’s role in the housing crisis.

“The $400 billion that the RBA printed in the early year or two of COVID and effectively handed over to retail banks, who then turn around and lend it into the property market, do you accept that that played a role in the housing price bubble that we’ve seen over the last five years?”, McKim asked in a tense parliamentary hearing.

“Certainly part of the way monetary policy works is through the housing market, but I would not accept that the Reserve Bank is responsible for the housing price issues in this country”, Bullock responded.

“The problem is the lack of supply relative to demand, and when monetary policy eases and housing demand picks up, supply can’t pick up as quickly, and that’s where you end up”.

“But it’s not monetary policy’s responsibility to look after housing prices”, Bullock said.

McKim followed up by asking Bullock whether the capital gains tax (CGT) discount should be removed, to which she handballed to the government.

“I have done no particular analysis on what removal of the capital gains tax might do”, Bullock said. “It’s (not) my job to tell the government what they should do with the policy”.

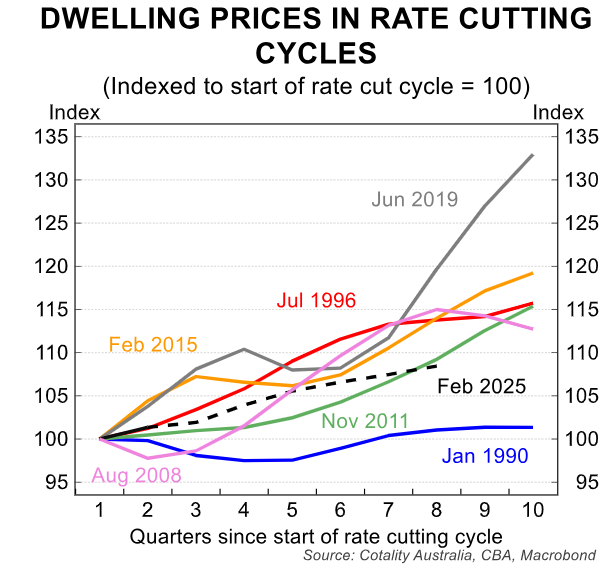

Everybody knows that periods of lower interest rates are typically followed by rises in home prices, and mortgage affordability and borrowing capacity are improved.

However, this doesn’t mean that the RBA is to blame for the nation’s deteriorating housing affordability.

The RBA has one tool at its disposal—changes in the official cash rate—that it is required to use to balance inflation and unemployment. Impacts on asset markets from changes in interest rates are merely a by-product.

The blame for Australia’s poor housing affordability instead falls on Australia’s governments and regulators, which control the rules and incentives around housing. For example:

- The Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA) controls macroprudential rules, including buffers and risk weights, around mortgage lending.

- The federal government controls immigration policy, with Australia experiencing the strongest growth in population in the advanced world this century, increasing demand.

- The federal government controls taxation policy, including tax concessions like negative gearing and the CGT discount, which incentivise property investment.

- The federal government controls fiscal policy, which has stimulated price growth via grants, shared equity, and 5% deposit schemes for first-home buyers.

- State governments control planning policies, which influences how housing supply responds to increases in demand.

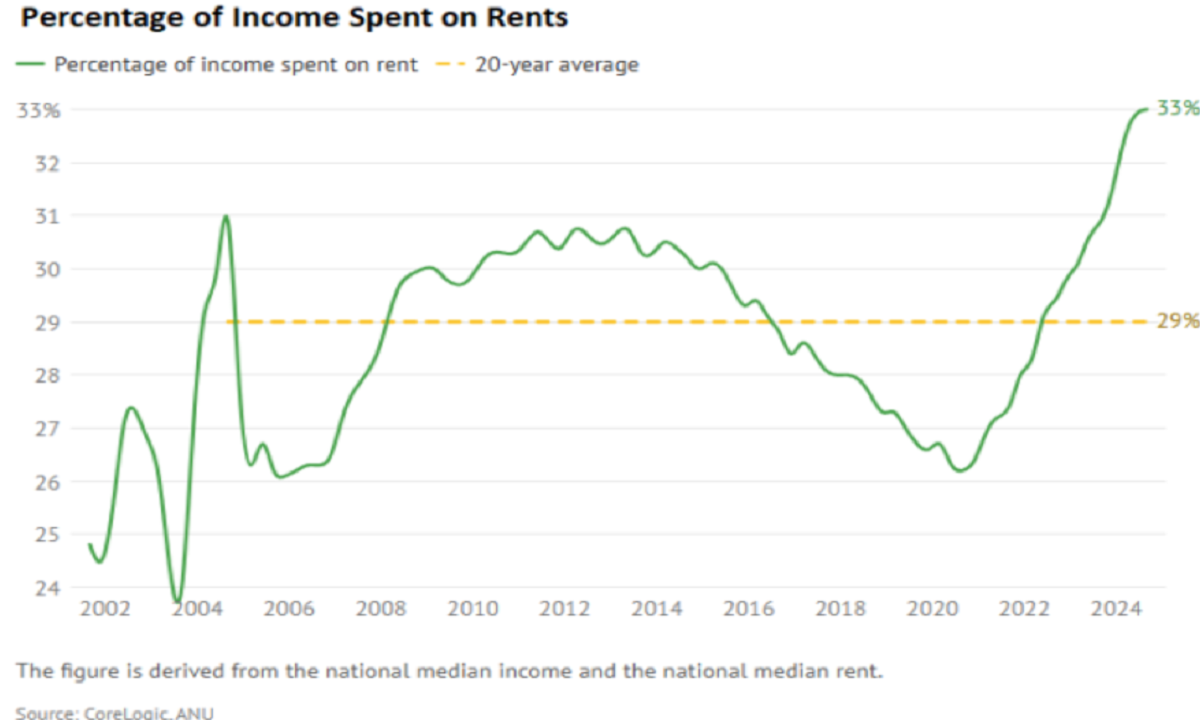

It is also worth noting that changes in interest rates have minimal impact on the rental market, which is suffering from the lowest vacancy rates on record alongside soaring rents, driven by recent record immigration levels.

Thus, attacking the RBA for Australia’s housing affordability crisis—both to purchase and rent—is both a distraction and misguided.

The blame must be slated at Australia’s policymakers, who have chosen to pump demand via excessive levels of immigration and idiotic taxation and housing policies.

My biggest criticism of the RBA is that it hasn’t publicly lambasted our governments’ dereliction of duty on housing and the economy and shamed them into action.

The RBA has also regularly run interference on immigration and other matters.