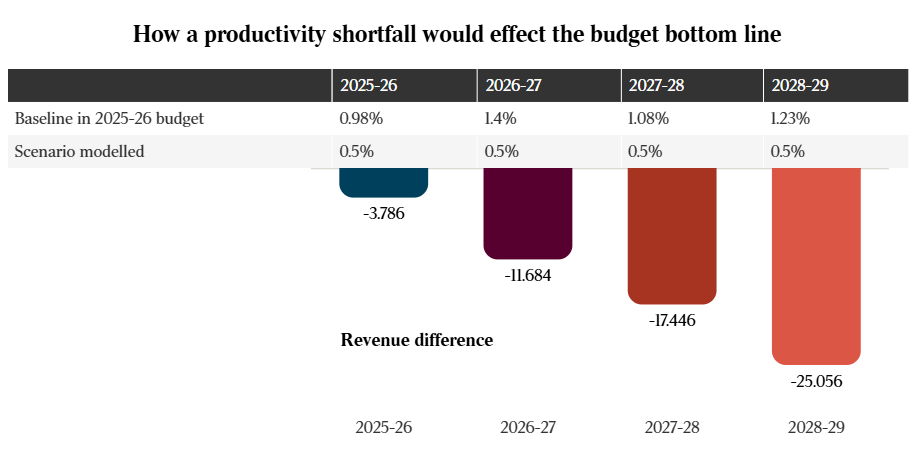

According to analysis from the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO), the federal budget could face a $58 billion revenue decline if average productivity growth remains at 0.5% over the next four years. This forecast is deemed credible by economists amid criticism of Treasurer Jim Chalmers’ higher estimate of 1.2%.

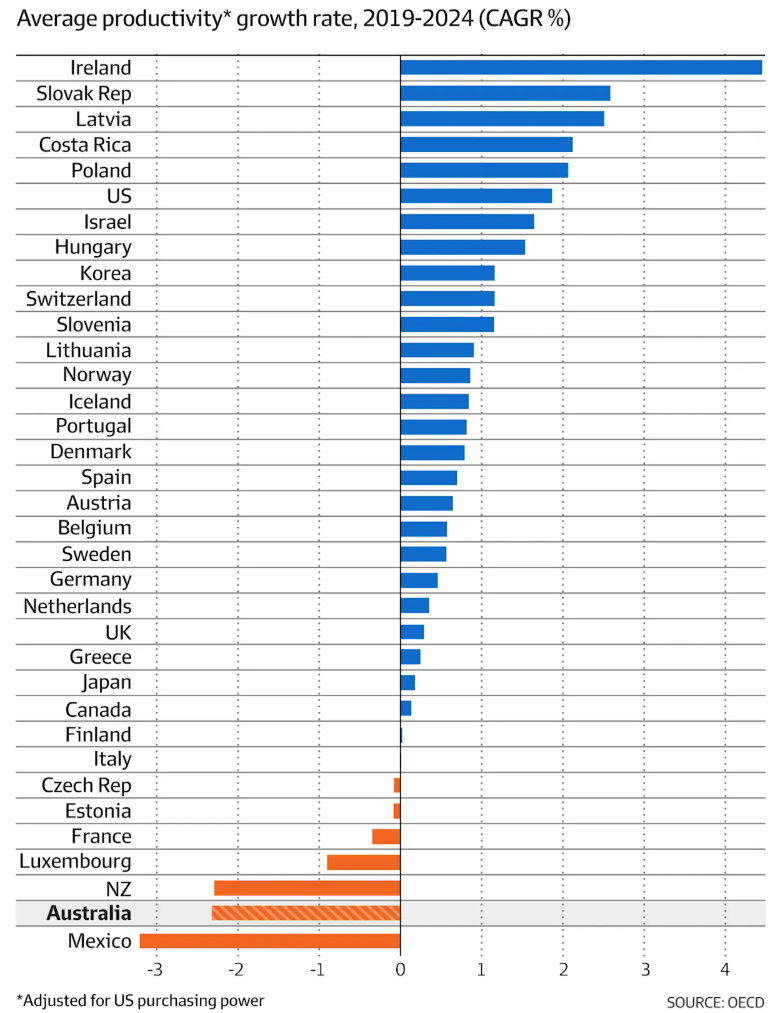

Australia’s productivity growth has averaged only 0.1% over the past eight years, with some economists suggesting long-term growth may only be around 0.4%.

HSBC Australia chief economist Paul Bloxham said Treasury’s 1.2% productivity growth assumption was “unrealistically high” and the RBA was being optimistic in assuming productivity growth would hit 0.7% by December 2027.

“Our working assumption is actually that productivity will potentially be even weaker than that (the RBA’s assumption)”, he said.

Bloxham believes the long-term average for productivity growth would be about 0.4%–below the PBO figure that showed a near $60 billion budget hit.

“What we have averaged over the past decade is about 0.1 per cent”, Bloxham said. “The RBA … revised down their forecast in August (but) they harked back to a working assumption that was a 20-year average”.

“But our view is the earlier period had a lot more reform that was done and was still holding up productivity. We think the last decade is more representative and we are still assuming a stronger profile than that decade’s average”, he said.

Independent economist Saul Eslake said the 0.5% assumption was credible, arguing this would “represent a pick-up” in productivity growth.

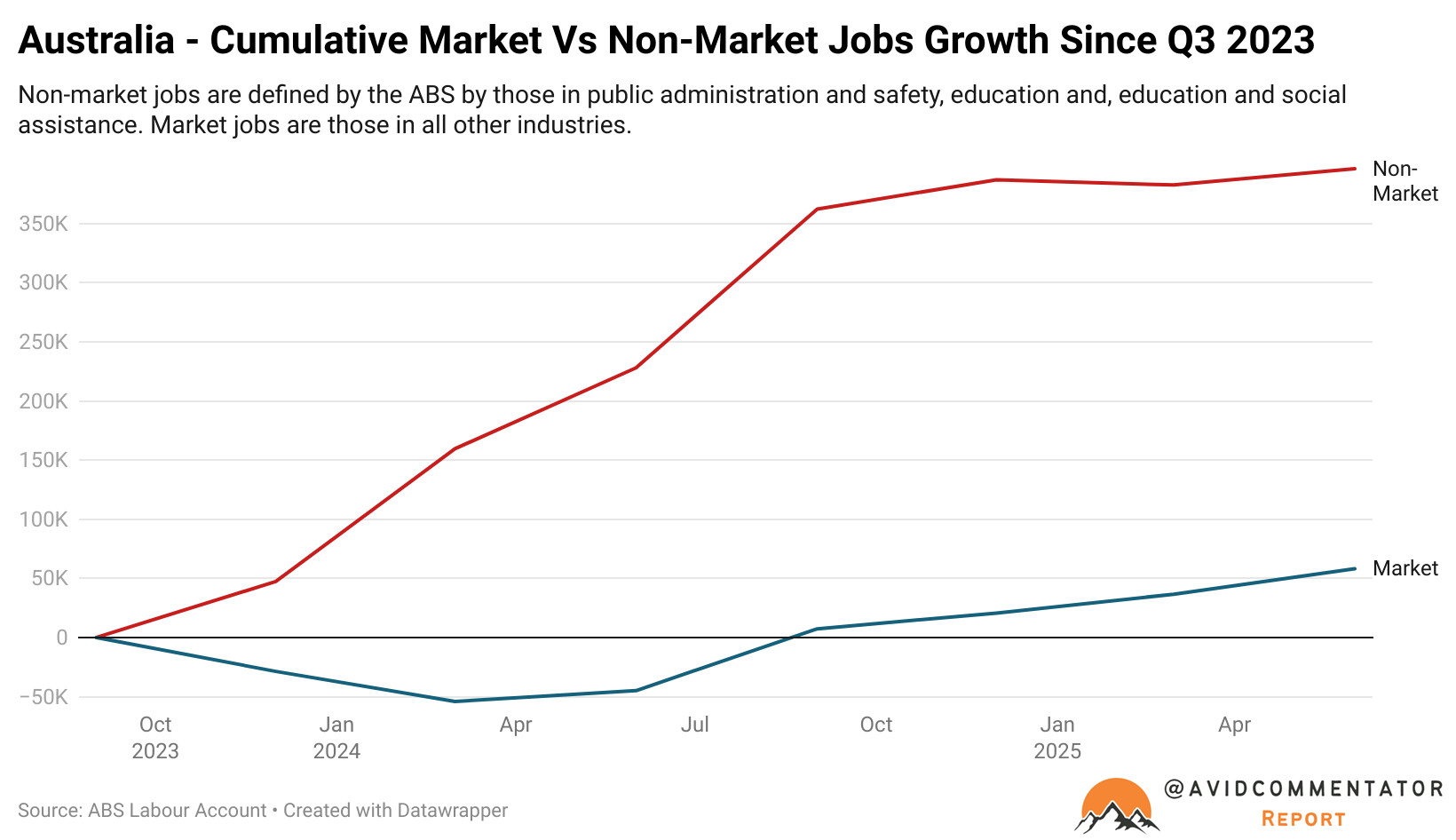

Australia’s recent productivity growth has been severely impacted by the unprecedented increase in non-market jobs, which have driven around 60% of the nation’s job growth since the pandemic.

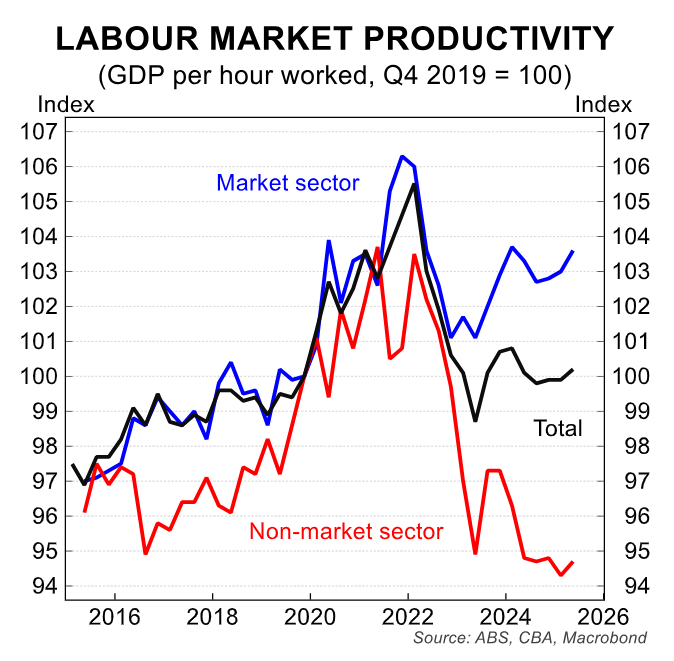

As illustrated below, productivity growth in the non-market sector has collapsed, pulling down overall productivity growth.

Productivity growth should, therefore, naturally rebound somewhat once the market sector takes over as the main driver of job creation. However, the longer-term productivity outlook for the nation remains soft.

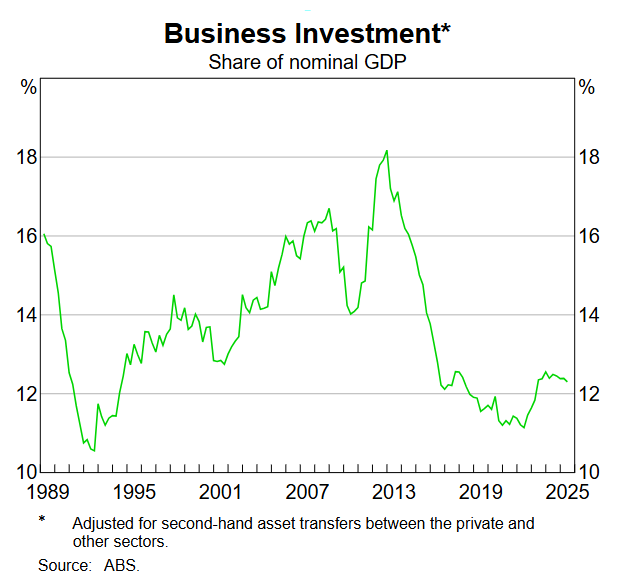

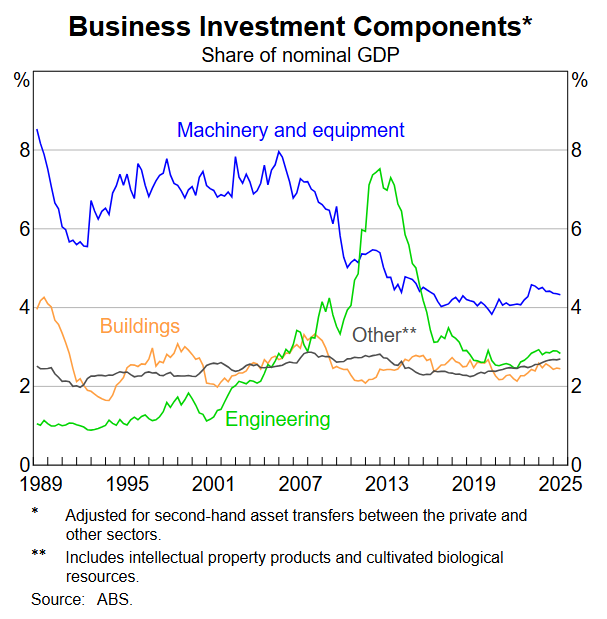

Private business investment as a share of GDP remains near recessionary levels in Australia.

In particular, investment in new machinery and equipment—vital to increasing worker productivity—are tracking at historically low levels as a share of GDP. At 4.3% of GDP, it is tracking at around half what it was two decades ago:

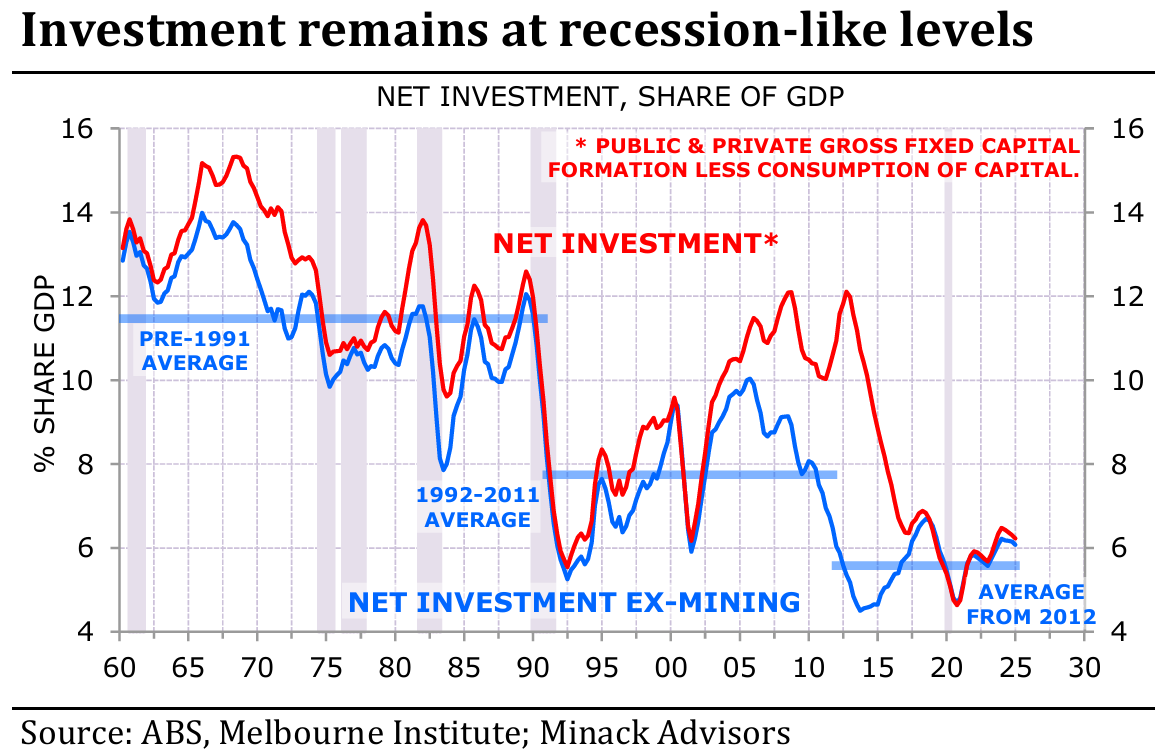

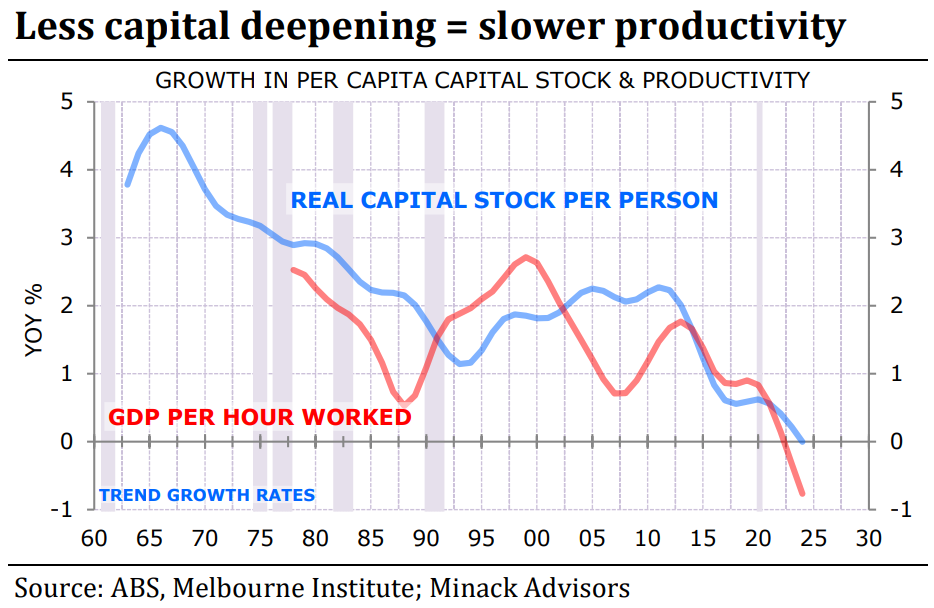

Leading independent economist Gerard Minack likewise illustrated that net investment in Australia is tracking at recessionary levels:

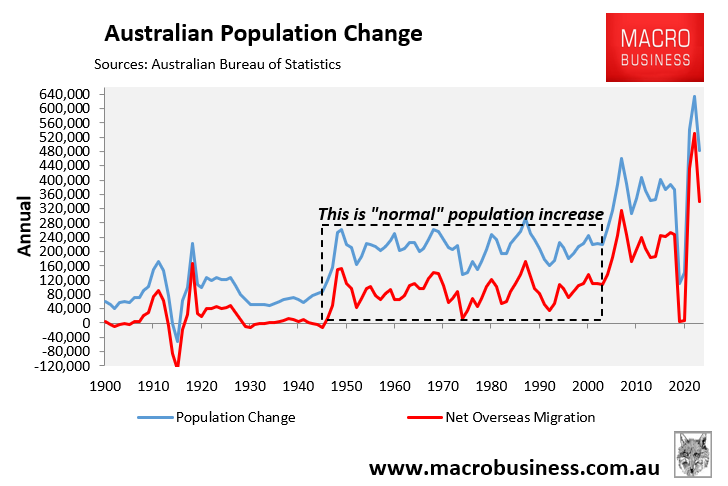

At the same time, Australia’s population has grown aggressively due to mass immigration.

As a result, the quantity of capital invested per person has decreased, which has dragged the nation’s productivity growth and standard of living down.

Australia has failed to equip the millions of additional migrant workers with the necessary tools, machinery, and technology. It hasn’t provided enough dwellings and infrastructure for the millions of additional families.

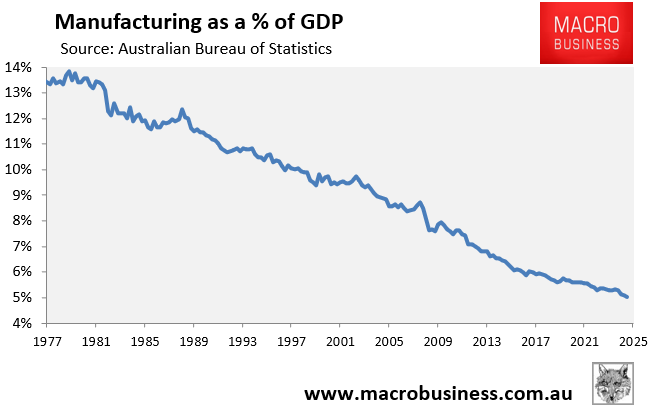

It is hard to see how Australia can realistically increase the capital-to-labour ratio, i.e., experience ‘capital deepening’, and improve productivity growth when the manufacturing sector is in terminal decline amid rising energy costs.

With energy costs set to soar amid net-zero policies and gas policy failures, Australia will inevitably continue to deindustrialise as manufacturing relocates to lower-energy-cost nations. As a result, companies will wind down capital investment in Australia.

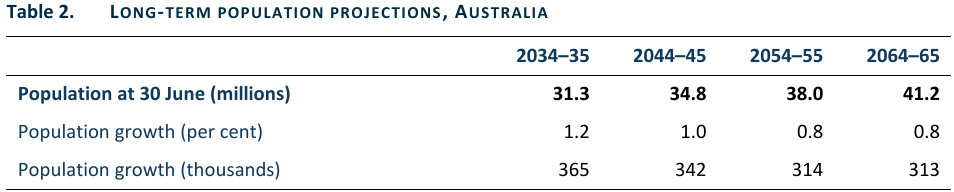

Meanwhile, the federal government has committed to increasing the nation’s population by 13.5 million over the next 40 years via high net overseas migration.

Source: The Centre for Population (December 2024)

Adding the equivalent of another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane to Australia’s current population in only 40 years will require an unprecedented amount of investment in business, infrastructure, and housing to maintain the capital stock per person.

Such unprecedented levels of investment will be impossible to achieve and will inevitably result in the economy suffering from further ‘capital shallowing’ and slower productivity growth.

In short, Australia is facing a low-productivity future, with declining living standards because we are hell-bent on committing energy policy suicide, deindustrialisation, and flooding the nation with vast volumes of low-skilled migrants.

The federal budget will also suffer from declining taxation revenue.