NSW Premier Chris Minns is another housing phoney

In September 2023, just as Australia’s net overseas migration was hitting its highest level in history (i.e., 556,000), NSW Premier Chris Minns told ABC’s 7.30 Report that he supported record immigration levels, claiming that more migrants were needed to build houses and apartments in the state.

“We’re supportive of the commonwealth government’s decision to lift immigration into New South Wales, notwithstanding the fact that we’ll take, not the majority but the greatest number of inbound immigrants”, Minns said.

“A lot of that labour coming into the state will be directed to the housing market and we need them to build houses and apartments”.

Minns conveniently forgot to mention that very few migrants actually work in construction.

The latest report from the government body Build Skills Australia explained how few recent migrants actually work in construction. Therefore, immigration is making Australia’s housing shortage much worse by pumping demand without adding to supply.

Over the last 20 years, the residential construction sector has consistently employed between 4.0% and 5.0% of the working-age population in Australia. This ratio offers a reasonable benchmark for the level of labour resourcing required to meet housing needs. It implies that for every 100 new residents, 4–5 additional residential construction workers are required to support their housing needs.

If immigration is to make a net positive contribution to labour supply, the proportion of immigrants employed in residential construction must exceed this ‘hurdle rate’ of 4.0%-5.0%. Otherwise, local resources will need to be diverted from other activities to meet the housing needs of the growing population.

However, only 3.2% of recent immigrants—those who arrived in the last decade—are employed in the residential construction sector. This indicates that immigration’s contribution to population growth has not been matched by its contribution to the workforce needed to construct housing for these additional residents…

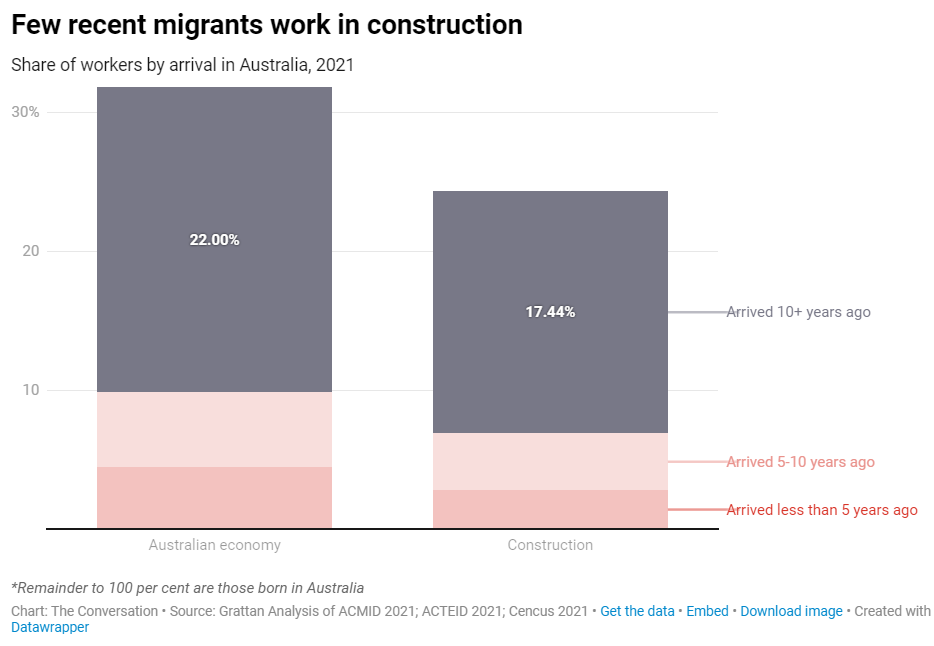

Build Skills Australia’s analysis aligns with data compiled by the pro-migration Grattan Institute, which showed that migrants are vastly underrepresented in the construction industry:

“Migrants who arrived in Australia less than five years ago account for just 2.8% of the construction workforce, but account for 4.4% of all workers in Australia”, Grattan reported.

Leading pro-Big Australia shills Peter McDonald and Alan Gamlen also admitted that Australia’s immigration is worsening Australia’s housing and infrastructure shortages by lifting demand without adding to labour supply:

“In 2023-2024, the permanent programme delivered just 166 tradespeople, negligible against national needs. By contrast, more than 5,000 entered via the temporary skilled stream in 2024-2025”.

“Even this is insufficient to close the gap”.

As a result, Australia’s immigration program is directly driving Australia’s housing shortage by adding far more to demand than supply.

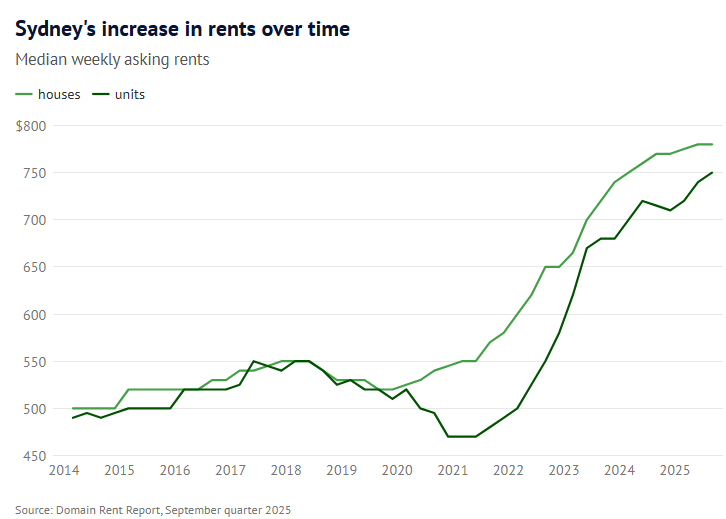

Meanwhile, the housing situation in Sydney continues to worsen.

Domain reported that the cost of renting a median Sydney home hit a record high in September.

As illustrated below, the median weekly Sydney house rent was $780 in the September quarter of 2025, up $240 (44%) from $540 in the September quarter of 2020.

The median Sydney unit rent was $750 in the September quarter of 2025, up $255 (52%) from $495 in the September quarter of 2020.

Domain chief of research and economics, Dr Nicola Powell, said that tenants had hit their “affordability ceiling” amid “relentless rental hikes over the previous few years”.

Domain also reported that Sydney’s rental vacancy rate was only 0.9% in the September quarter, well below the vacancy rate of about 3% that reflects a balance between tenants and landlords.

With NSW housing demand running way ahead of supply, Premier Chris Minns has lamented that excessive housing costs are destroying Sydney and has promised to open the city to more high-rise apartment development.

NSW Premier Chris Minns has said the state’s housing crisis is so pervasive that it has infected all parts of public policy from industrial relations to shortages in skilled labour and the cost of living.

In his strongest comments to date on the housing quagmire facing NSW, Minns also doubled down on councils that try to stand in the way of development, reminding them “local government is just an act of the state parliament”.

“The biggest problems we face all come back to housing,” Minns said in an exclusive interview.

“We’ve got industrial relations problems; they’re really housing problems. We’ve got a skilled labour shortage problem, it’s really a housing problem. We’ve got a cost of living, family budget problem – it’s really a housing problem.

“The biggest element of every family budget is just housing costs…

Minns said there should be no area of Sydney immune from more density.

The obvious question is: why won’t Chris Minns admit that population growth via immigration is too high? And why won’t he lobby the federal government to lower the migrant intake?

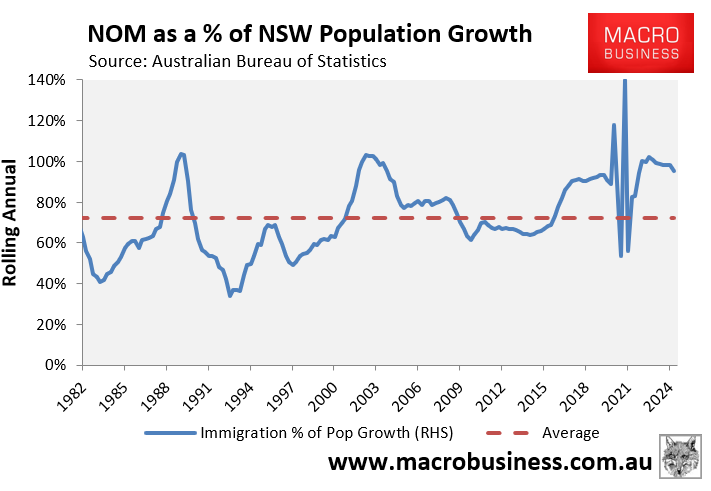

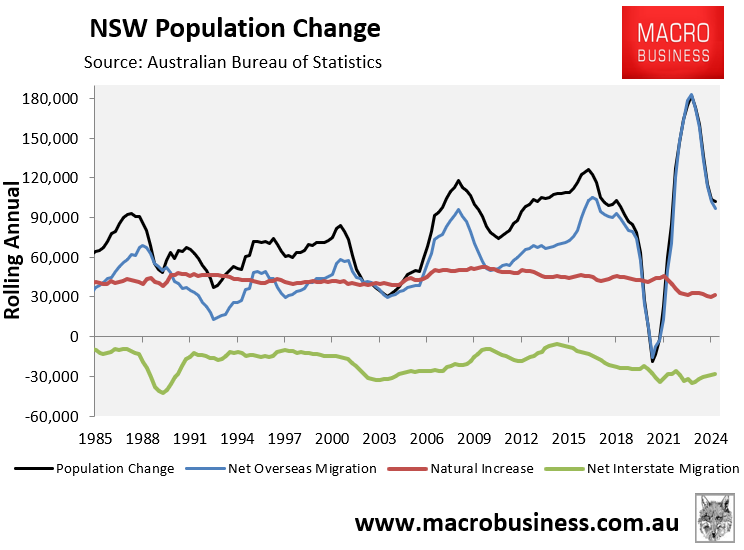

The primary driver of Sydney’s population growth and therefore household formation is net overseas migration.

In the year to the March quarter of 2025, 96,800 net overseas migrants landed in New South Wales, accounting for 95% of the state’s population increase.

Any housing shortage in New South Wales, therefore, is directly attributable to the state’s excessive immigration intake.

The solution to the housing crisis is abundantly clear: lower immigration to a level below the capacity to supply housing and infrastructure.

Otherwise, the state’s housing situation will deteriorate.

Dishonest politicians like Chris Minns, who refuse to recognise the demand side of the housing equation, are the problem.