India cannot rescue Australia from itself

There is a commonly held economic narrative that Indian demand for commodities will compensate for the reduction in Chinese demand as China’s economy slows and rebalances toward a consumer-focused model.

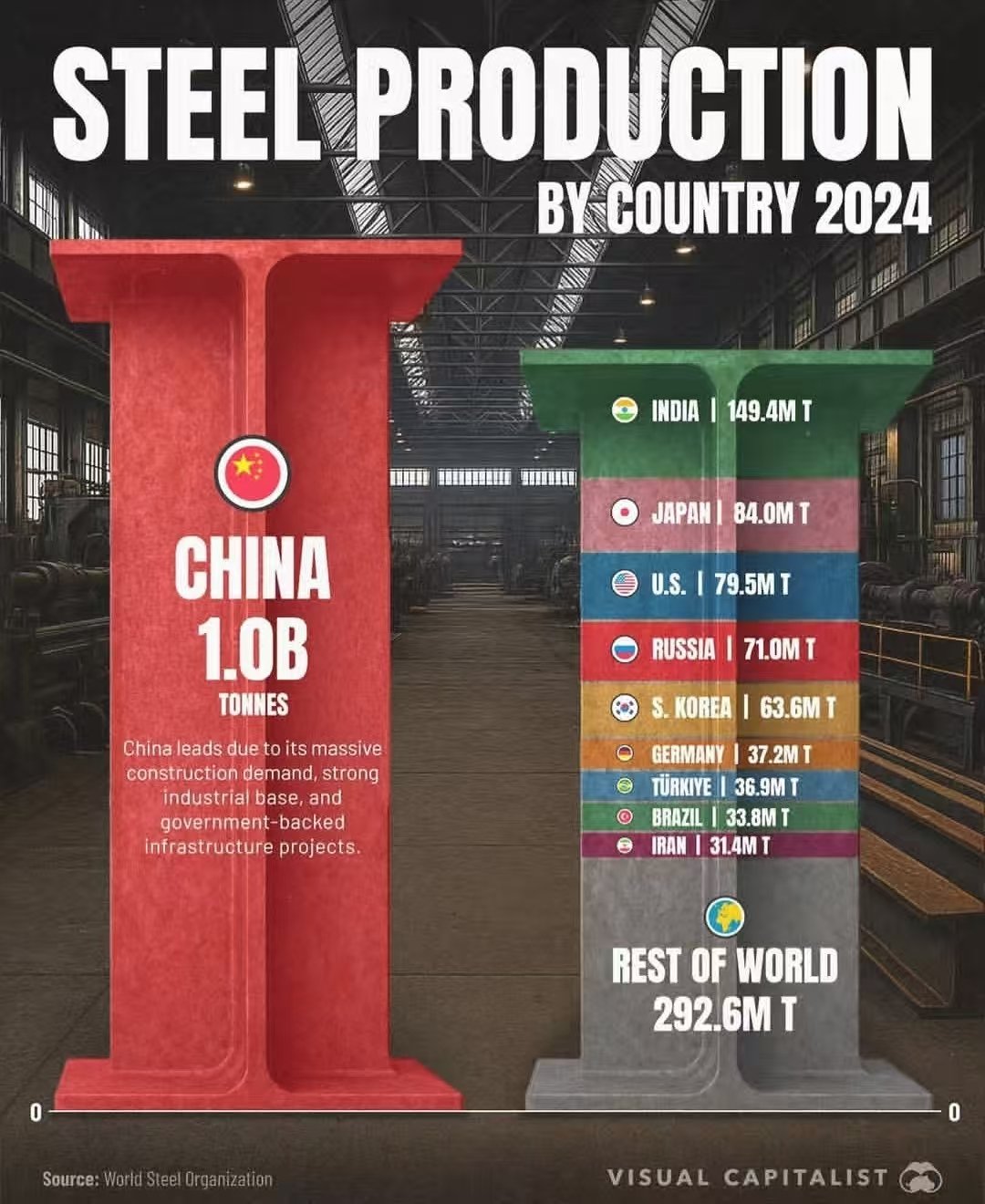

The reality of this narrative is perhaps best summed up by the chart below from Visual Capitalist, which shows that China produced more steel in 2024 than the rest of the world combined and more than six times as much as India.

Therefore, the belief that India’s growth will stimulate robust demand for Australia’s commodities is unfounded, particularly for iron ore, the country’s most valuable export.

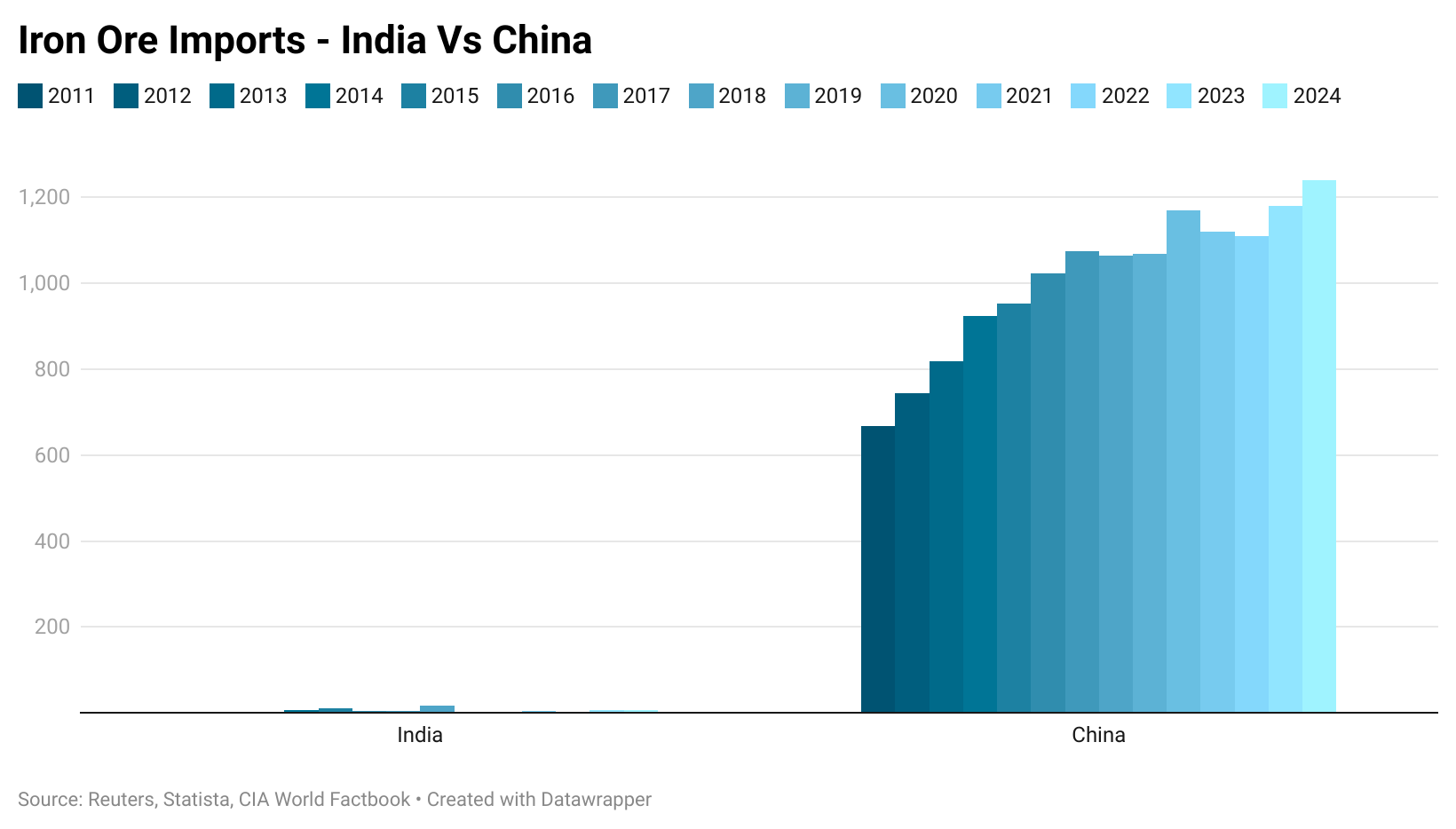

Unlike China, India is largely self-sufficient in iron ore and generally a net exporter of the bulk commodity.

Despite the meteoric rise in India’s steel production relative to any other industrialised economy bar China, China imports more iron ore in two days than India does in an entire year.

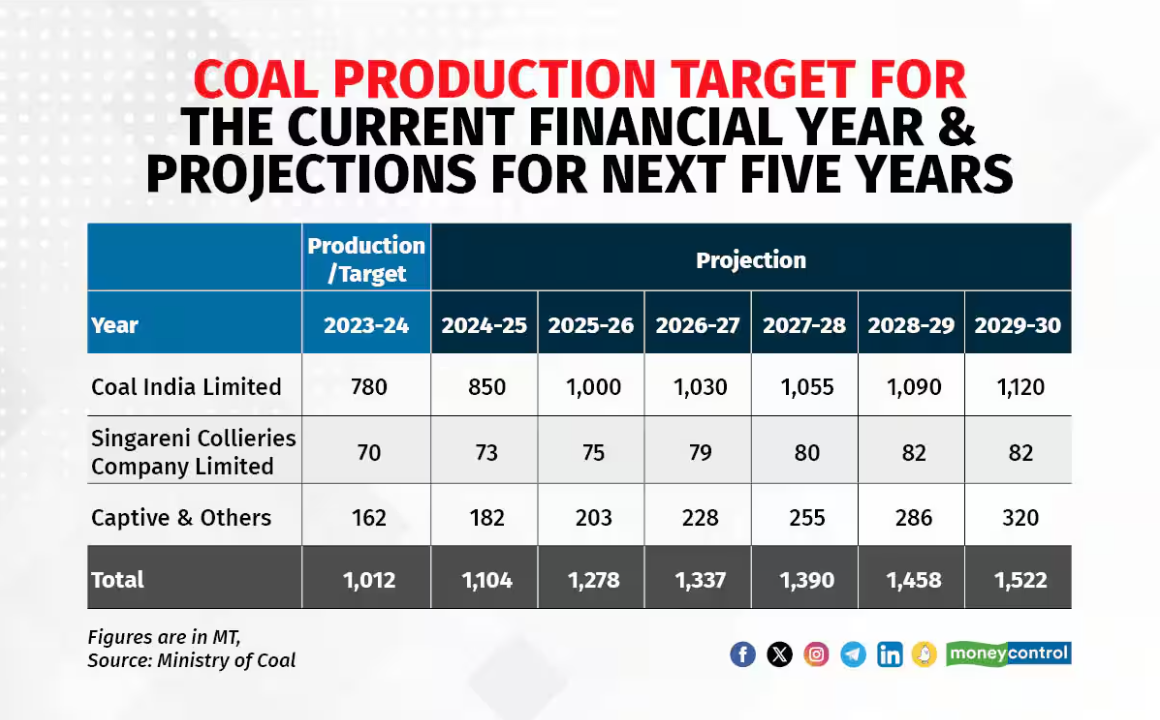

TThe simple reality is that India is following a strategy that significantly differs from China’s, with a strong emphasis on self-sufficiency.

This push extends well beyond the realm of iron ore and steelmaking, with India set to expand its domestic coal production by over half a billion tons per year by the 2029–30 Indian fiscal year.

The Symbiotic Relationship

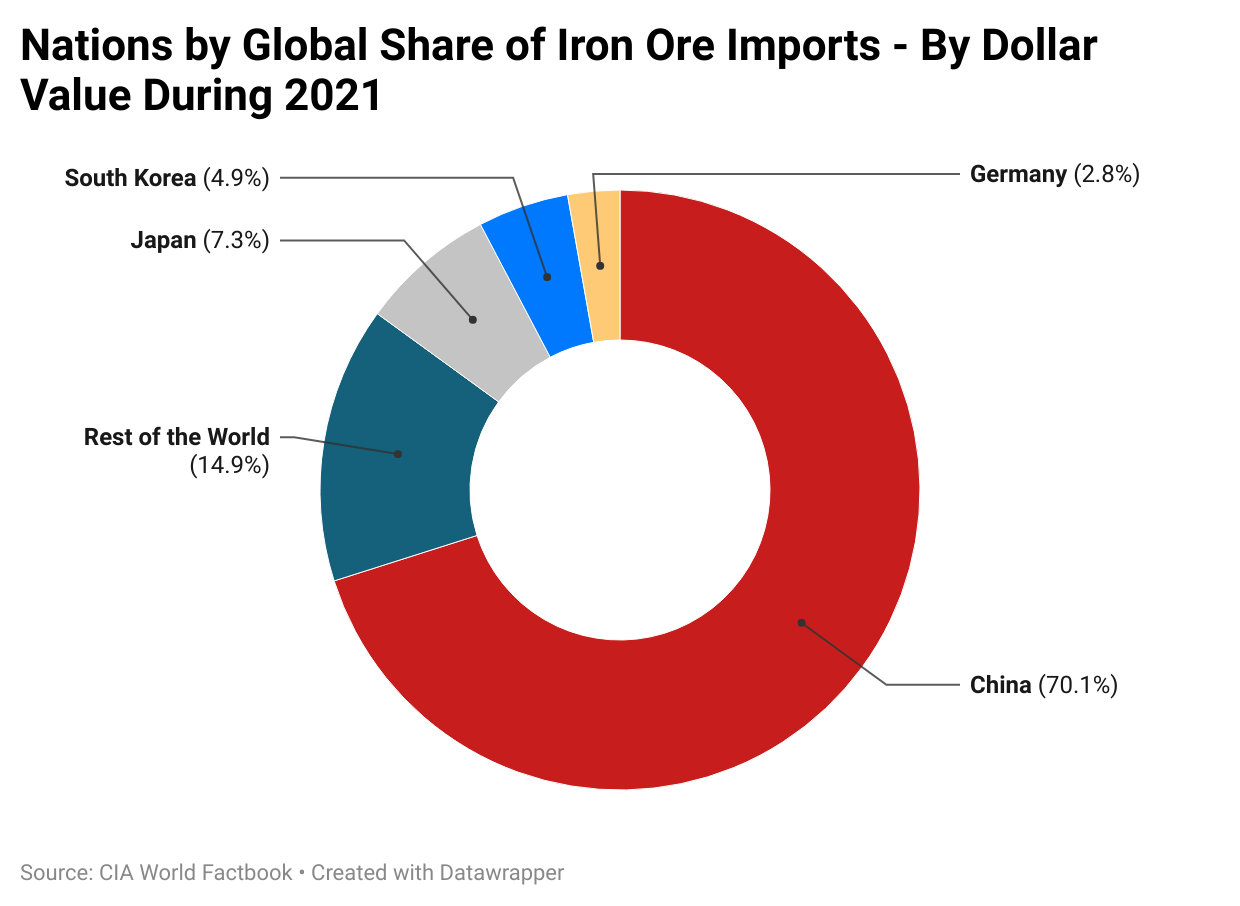

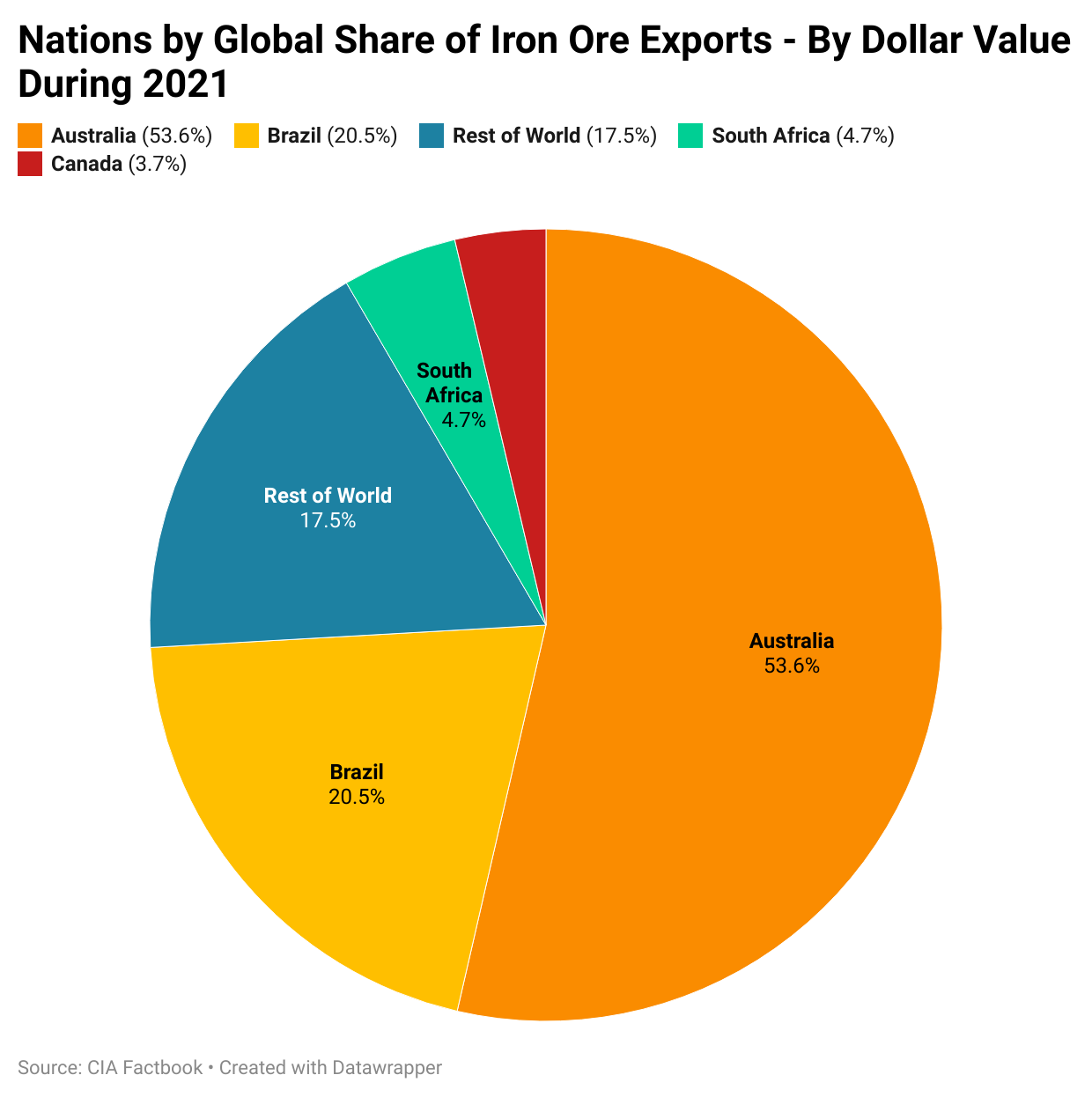

When examining a chart of global iron ore imports and exports, it immediately becomes clear how reliant China and Australia are on each other when it comes to this commodity.

On one hand, China imports twice as much iron ore as the rest of the world combined, with India not making the top 15 nations for import volumes.

That is also to say nothing of Indian iron ore exports, which further add to global supply.

On the other hand, Australia exports more iron ore than the rest of the world put together.

In short, Australia’s economy is for better or worse, shackled to the fortunes of the Chinese industrial sector.

WWhether it’s iron ore, thermal coal, coking coal, LNG, or copper, the Chinese industry’s health is vital to the Australian federal budget as well as the broader economy.

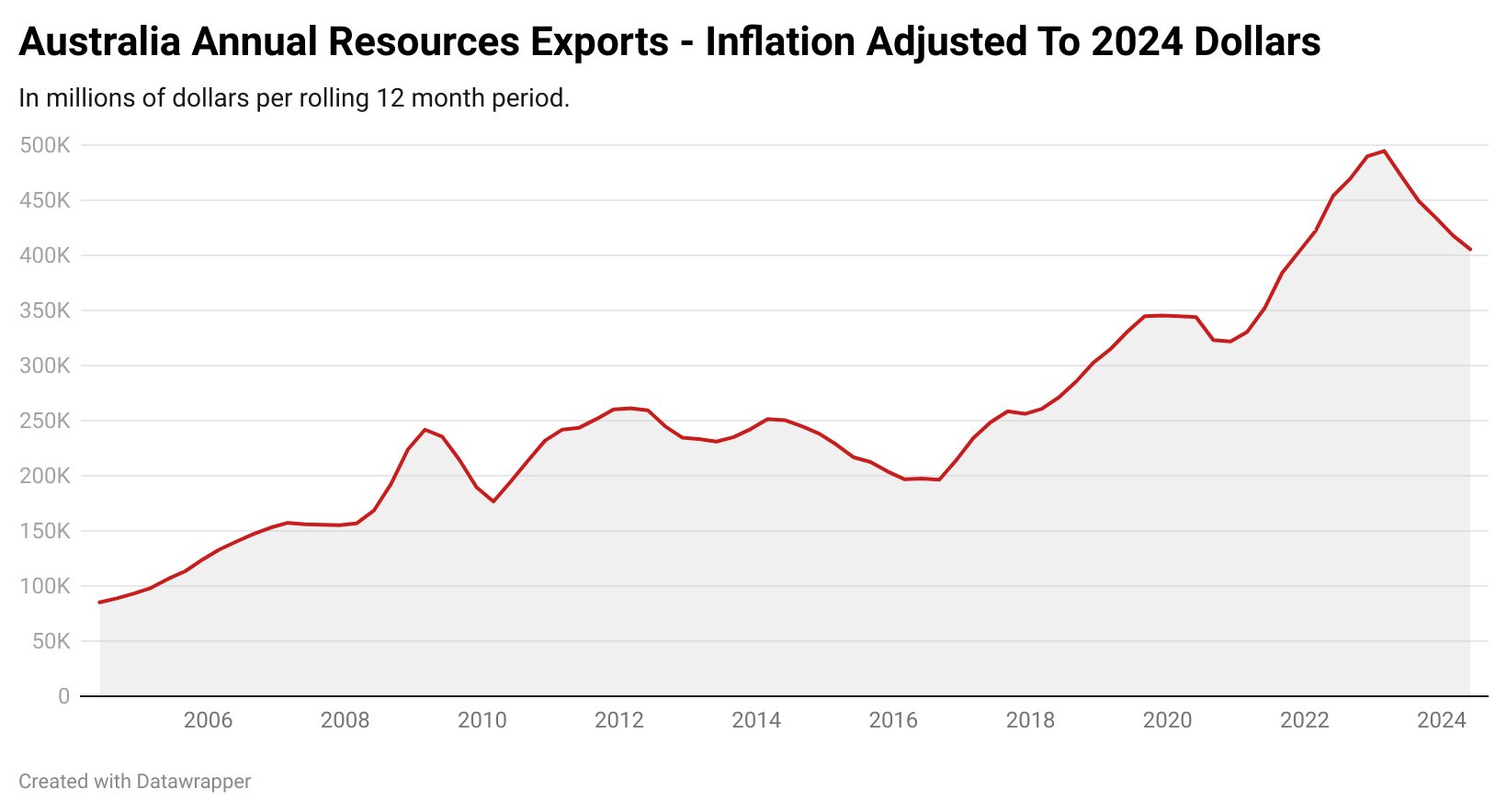

With total real resources exports at times pushing almost half a trillion dollars per year, the resources sector has been the gift that has kept on giving for the nation’s coffers, much of which is driven by demand from the Middle Kingdom.

Ultimately, New Delhi has neither the ability nor the inclination to deliver Australia from whatever resource downturn-induced woes it may find itself on the road ahead.

While hope will likely remain in some quarters that India will be the new China when it comes to demand for resource exports in the second quarter of this century, the reality is the pathway New Delhi is pursuing is not in the same galaxy as beneficial to Australia as Beijing’s was historically.