How Labor secretly raised the permanent migrant intake

Former senior immigration department bureaucrat Abul Rizvi posted an article in Independent Australia where he explained how the Albanese government secretly increased the permanent migrant intake well above the official published level.

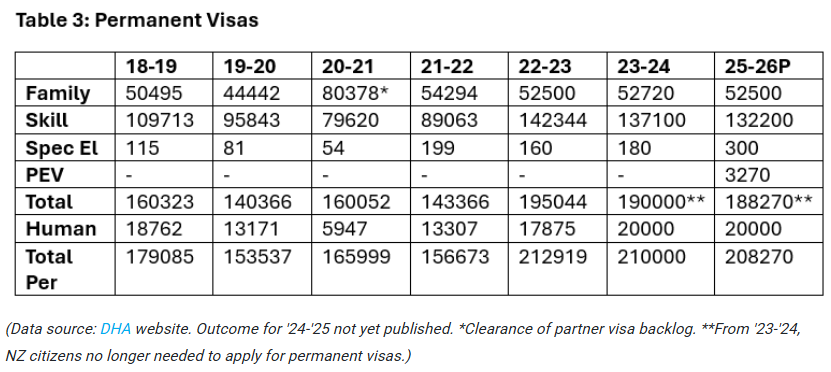

Rizvi showed how Labor “has significantly increased the size of permanent migration compared to the situation pre-pandemic (see Table 3)”.

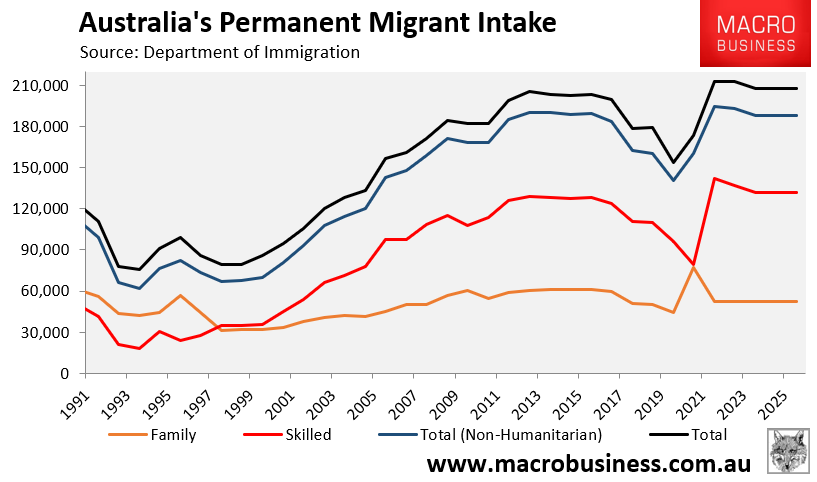

A time series chart of Australia’s official permanent migrant program (including the humanitarian intake) is provided below:

Rizvi then stated that “the headline size of the migration program now understates the actual level of permanent migration because”:

- “NZ citizens from ’23-’24 no longer need to secure permanent residence. Those places are now taken by other nationalities, effectively increasing the size of the migration program while NZ citizens access Australian citizenship directly; and”

- “Pacific Engagement Visas, which are permanent residence visas, for no good reason, are not included in the permanent migration program”.

Rizvi’s claims are similar to those from William Bourke, founder of the Sustainable Australia Party, who noted in September that Australia’s permanent migrant program is actually understated by at least 50,000 for the following reasons:

- “It does not count the annual permanent Humanitarian Program of around 20,000 (soon to be 27,000), being permanent resettlement for refugees, etc”.

- “It does not count New Zealanders, who have unlimited rights to permanent residency in Australia under the Trans-Tasman Agreement (TTA). The TTA has produced a post-2000 annual average of around 30,000 net migrants to Australia”.

- It does not include “Labor’s new Pacific Engagement Visa program, which provides 3,000 further permanent visas per year”.

Bourke argues that these additions “increases Australia’s annual permanent migrant intake by roughly 27% to around 235,000 per annum”.

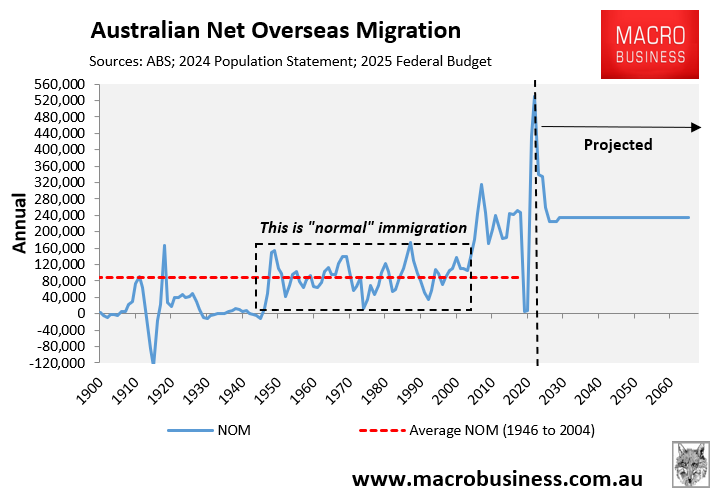

Interestingly, 235,000 is also the long-run net overseas migration projection from the Intergenerational Report and the Centre for Population.

“For the sake of transparency and truth, this [235,000 figure] should all be reported and counted in the Permanent Migration Program headline figure”, Bourke argues.

“Putting COVID-impacted fluctuations and the recent loosening of various temporary migration programs by the Albanese Government aside, these two omissions from the permanent migration program calculation largely bridge the gap to the Australian Bureau of Statistic’s net overseas migration (NOM) figure”.

I have always argued that the permanent migrant intake is the most significant long-run driver of net overseas migration and population growth, since temporary migrants must by definition eventually return home if they cannot gain permanent residency (even though this process can take many years).

William Bourke shares my view:

“The permanent migration figure is the most important figure when it comes to immigration and ultimately the more important issue of population growth, because net overseas migration includes many temporary migrants who depart, particularly without a guaranteed or likely place in the Permanent Migration Program”.

Bourke has also called for “transparency and truth” in the permanent migrant program:

“If Kiwis and refugees are permanent, why have successive Australian governments intentionally materially understated the annual permanent migration intake number by leaving them out of the count? Could it have something to do with the ‘optics’ of a ‘2’ in front of the annual permanent migration intake number instead of a ‘1’, and the related majority public opposition to excessively high immigration in almost every independent public opinion poll in memory?”

“Australians need transparency and population policy reform, not smoke and mirrors. Otherwise we will see even more disaffection with politics and governments, and more extremists”.

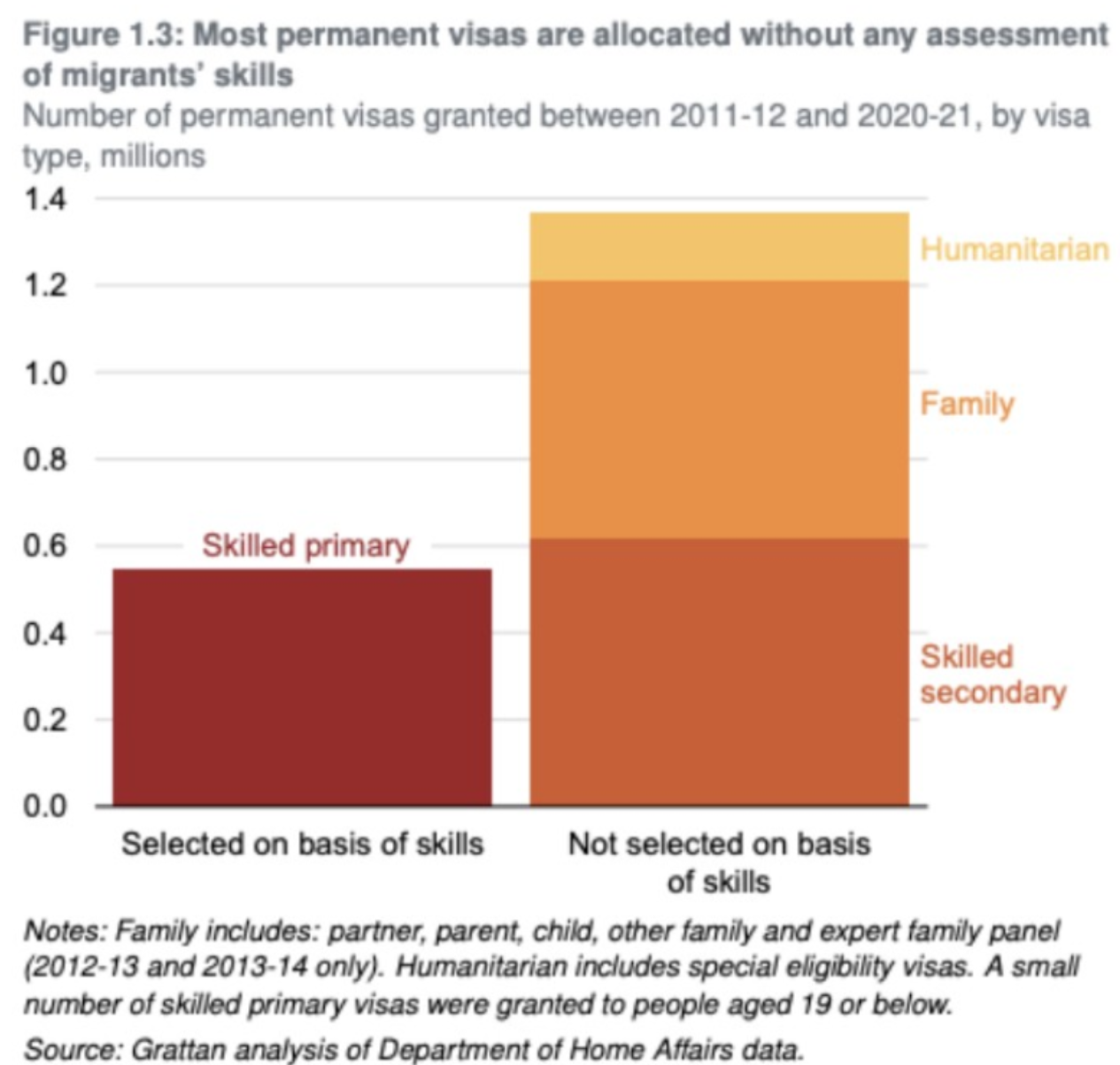

Not only is Australia’s permanent migrant program too large, crush-loading housing and infrastructure, but it is also mostly unskilled:

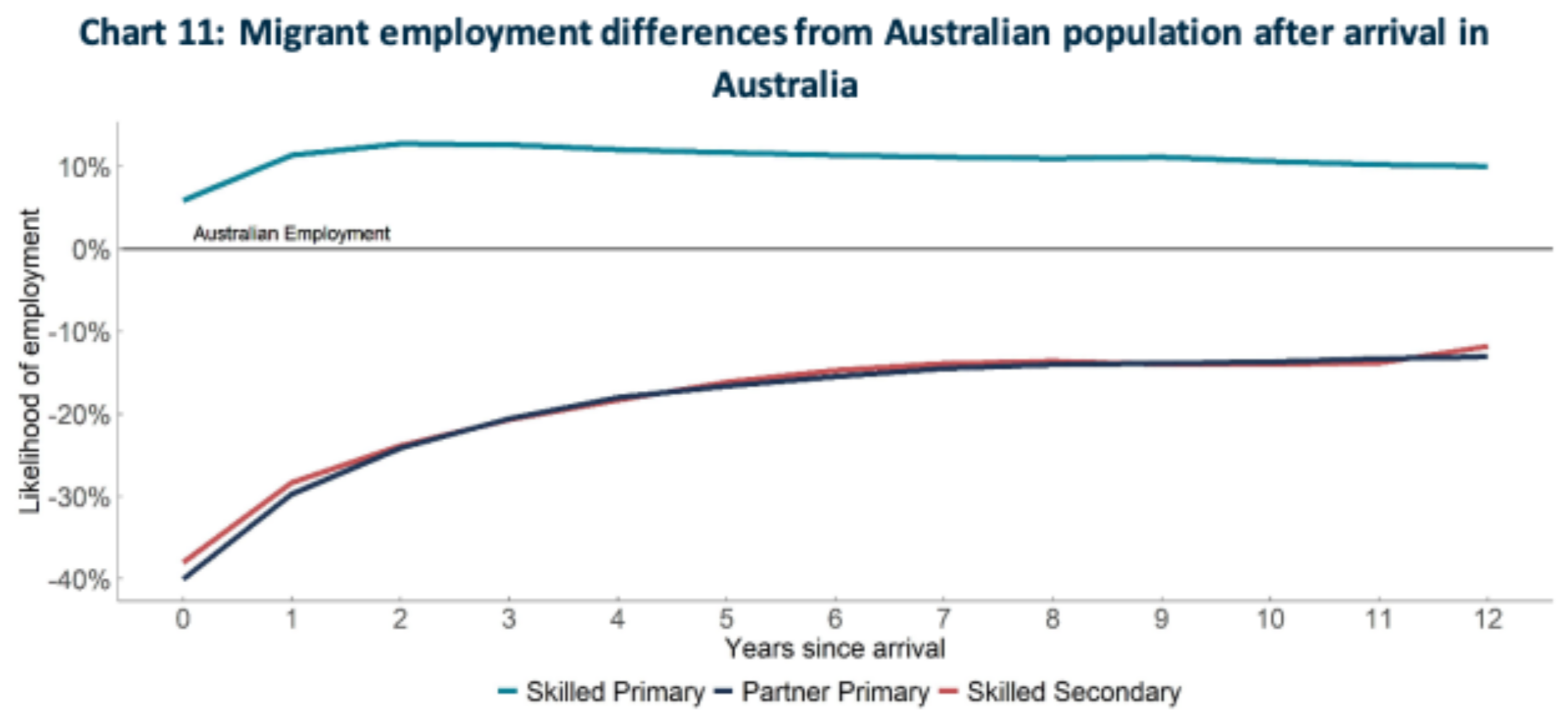

The Australian Treasury also found that the labour market outcomes of these unskilled migrants are poor:

Given Australia’s chronic housing and infrastructure shortages and poor productivity growth, the logical solution is to run a significantly smaller permanent migration program that is focused on highly skilled, employer-sponsored applicants.