There are two main reasons why the federal government supports running a high immigration program.

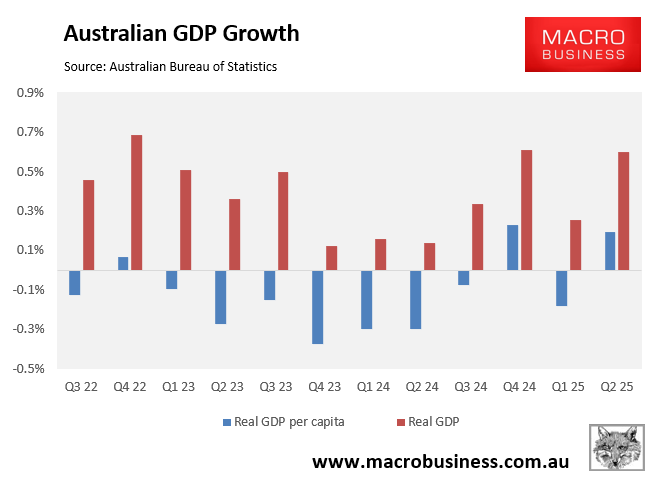

First, immigration benefits overall economic growth, as measured by headline GDP. Running a high immigration policy allows the federal government to pretend to be a competent economic manager, even when per capita GDP growth is poor and individual living standards are falling.

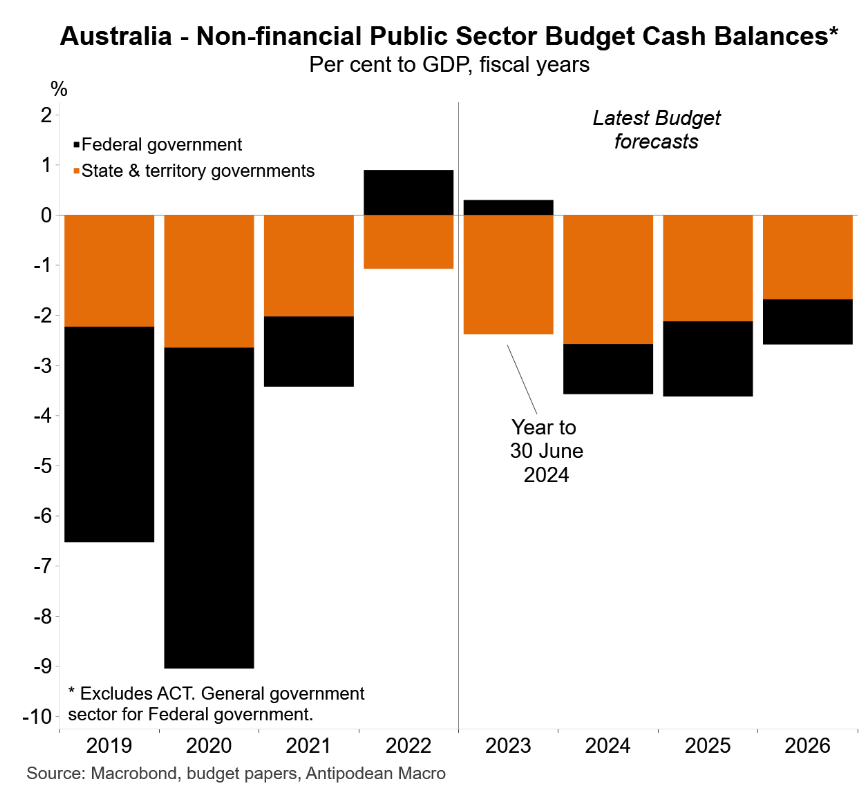

Second, immigration bolsters the federal budget by increasing the number of workers, personal income tax receipts, and corporate tax receipts (through the larger economy).

However, while record immigration benefits the federal budget, state governments, which are primarily responsible for the infrastructure and services required by growing populations, are facing overwhelming debt burdens.

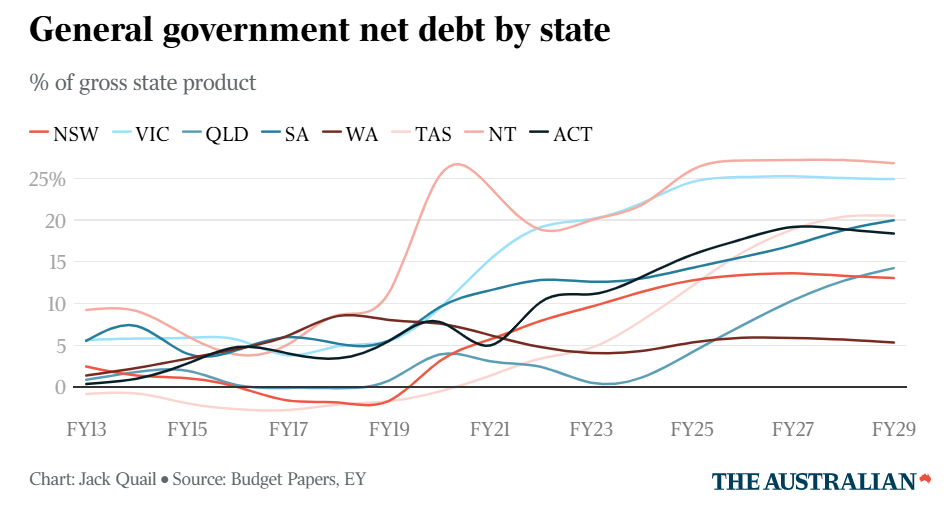

Last year, global ratings agency S&P cautioned that Australia’s total state debt was growing faster than comparable subnational equivalents in industrialised countries.

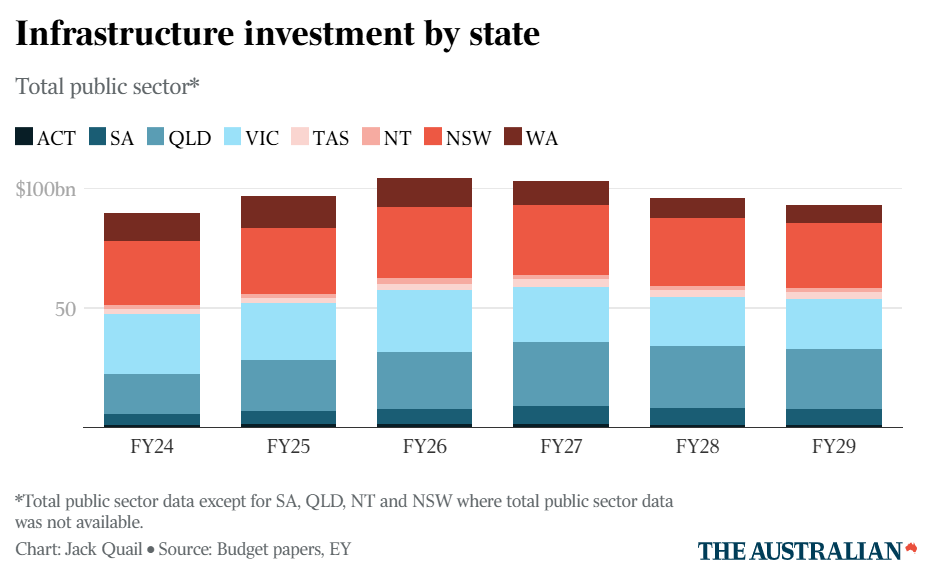

Martin Foo, director and lead analyst at S&P, blamed the rising debt on a statewide “infrastructure binge” on road, rail, health, and energy projects worth $348 billion over four years.

“In inflation-adjusted terms, this is about 1.7 times the size of the Marshall Plan that rebuilt post-war Europe”, he said.

EY forecasts that Australia’s state and territory governments will spend a record $104 billion on public infrastructure in 2025-26.

When the federal government’s asset investment program is included, total infrastructure spending across the country is expected to exceed $137 billion.

The states and territories are becoming more reliant on debt to fund infrastructure projects, with their aggregate net debt expected to reach $523 billion by the end of the decade, a tenfold rise from pre-pandemic levels.

According to Cherelle Murphy, EY’s chief economist, the increased debt burden may result in a downgrading of several states’ credit ratings.

“There are certainly some states … potentially going to face a credit downgrade because they really don’t have a plan to pull things back in again”, she said.

States and territories face about $23 billion in interest payments on general government debt, which will increase to $33 billion by the 2029 financial year.

Late last week, The AFR View lambasted the states for allowing their budgets to sink into the red via reckless infrastructure spending:

Across Australia, the balance sheets of states and territories are sinking into the red. While bond markets have traditionally punished big spending governments by ratcheting up borrowing costs, Australia’s states have faced little financial consequences for loosening the purse strings.

But the real concern is the intergenerational consequences of state government debt trajectories. That’s evidenced by a sobering analysis by The Australian Financial Review projects that combined state and territory debt will surge 37% over the next four years to a staggering $907 billion by 2028-29…

The states may soon discover there’s a fine line between nation-building and overbuilding. If treasurers continue to mortgage tomorrow for today’s projects, they risk being priced out of the future altogether, unable to borrow for the large capex projects essential to their long-term growth…

As usual, there was no acknowledgement that the states have to build these projects to accommodate the record population growth foisted upon them via the federal government’s mass immigration.

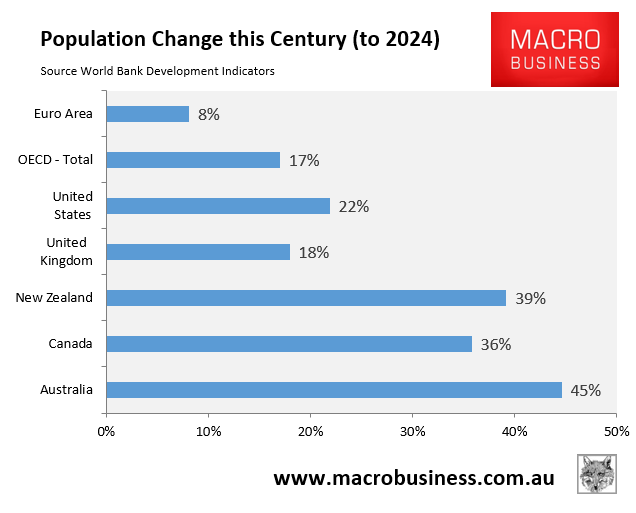

We can debate the cost and efficiency of these projects. However, we cannot deny that the 8.5 million (45% growth) in the nation’s population over the first 25 years of this century needs matching infrastructure.

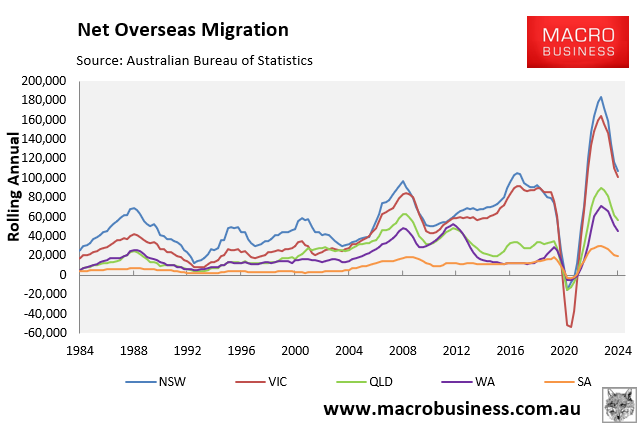

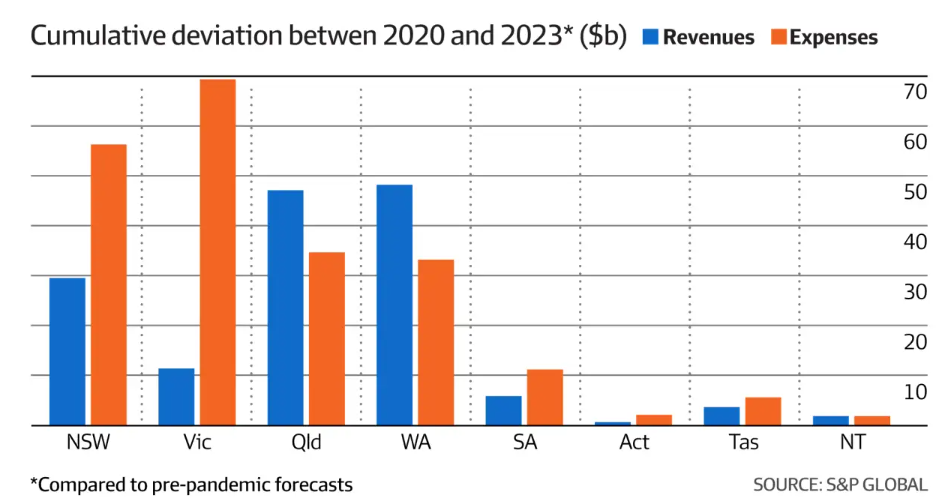

As shown in the chart above, the state debt growth is being driven by Victoria and New South Wales, which also attract nearly two-thirds of the nation’s net overseas migration.

Analysis from S&P, published in The AFR, showed that New South Wales and Victoria have suffered the largest shortfall between state revenue and expenses.

The federal government collects more than 80% of the nation’s tax revenue. As a result, the states struggle to finance health care, other essential services, and infrastructure necessary for their expanding populations.

The mass immigration policy of the federal government, which continually increases the demand for government services and infrastructure, exacerbates the fiscal imbalances for the states. This is especially true for New South Wales and Victoria, which receive the majority of net overseas migrants.

The debt situation will only deteriorate as the federal government continues to flood the nation with migrants (particularly to Melbourne and Sydney). State budgets will only plunge further into debt.

The federal government would be less enthusiastic about running a high immigration policy if it had to share the financial burden with the states.

The federal government views high immigration as a driver of growth and budget revenue, while the states and broader population suffer the fallout.