Australia’s housing market is turning sub-prime

Australia’s housing market is turning subprime. The proof is everywhere.

For more than a decade, the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA) flagged high loan-to-valuation ratio (LVR) mortgages as a key risk area.

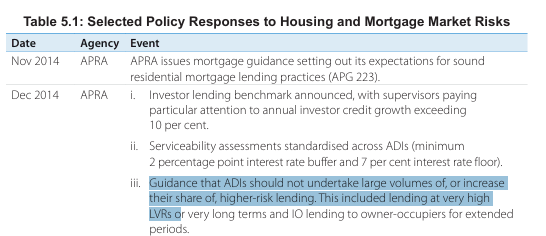

For example, in December 2014, APRA released guidance stating that “ADIs should not undertake large volumes of, or increase their share of, higher-risk lending. This included lending at very high LVRs”:

Earlier this year, APRA released its APG 223 Residential Mortgage Lending Update, which warned that “LVRs above 90% (including capitalised LMI premium or other fees) clearly expose an ADI to a higher risk of loss”.

APRA also stated that “prudent LVR limits help to minimise the risk that the property serving as collateral will be insufficient to cover any repayment shortfall”. As a result, “prudent LVR limits serve as an important element of portfolio risk management”.

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has also cautioned against high-LVR lending, noting increased risks of mortgage stress and default, especially during economic downturns:

Borrowers with high-LVR loans may also be more likely to face repayment difficulties in the event of a shock because their lower levels of equity mean they are less able to avoid such difficulties by selling their property or refinancing their loan.

A loan with a higher initial LVR is also more likely to lead to larger losses for lenders in the event of default, as the loan is more likely to be in negative equity at the point the property is actually sold (for a given rate of amortisation and housing price growth).

In light of the above warnings, it is disturbing that the Albanese government has institutionalised 95% LVR lending via its 5% deposit scheme for first home buyers, backed by taxpayers.

Any initial ‘benefits’ from this policy from increasing the share of first-home buyers will vanish once the increased buyer demand from the scheme is translated into higher housing prices.

In a few years, prices will have risen dramatically, and future first-home buyers will enter a market that is substantially more expensive than it would have been otherwise. They will have lower deposits and significantly larger mortgages than they would otherwise.

Then, if property values fall significantly, these buyers risk falling into negative equity.

Taxpayers will also be liable for any losses stemming from mortgage defaults, as the government will guarantee 15% of all first-home buyer mortgages under the scheme.

But it gets much worse. At the same time as the federal government has ignored regulator warnings about high LVR mortgages, thrown caution to the wind, and attempted to socialise the housing bubble, Australian lenders are busy dropping standards.

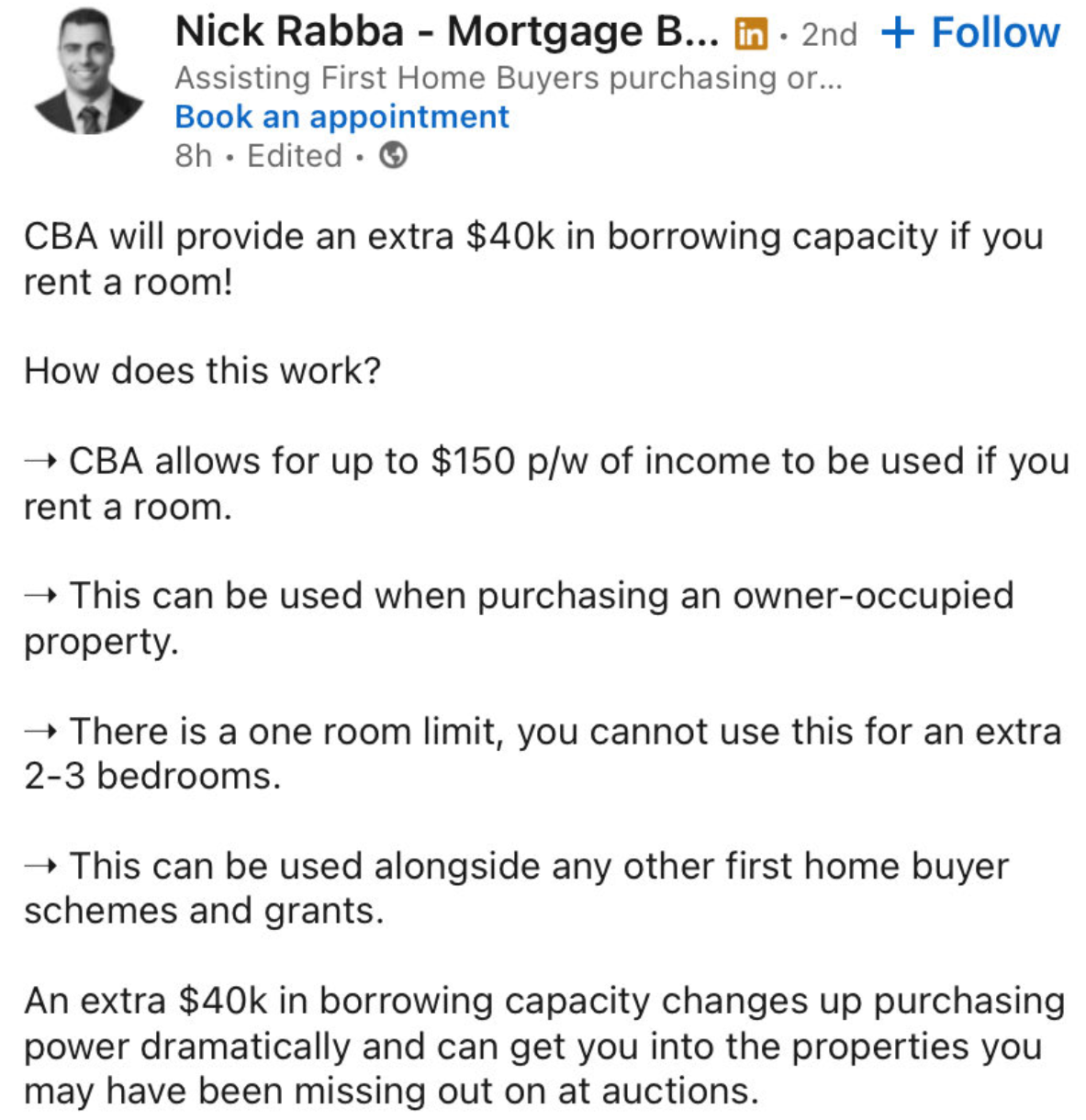

As noted on Wednesday, lenders this year have announced new stimulatory mortgage products, including 40-year mortgage terms and 10-year interest-only terms without reassessment. The CBA also announced this week that it will provide buyers with $40,000 in extra borrowing capacity if they rent out a room:

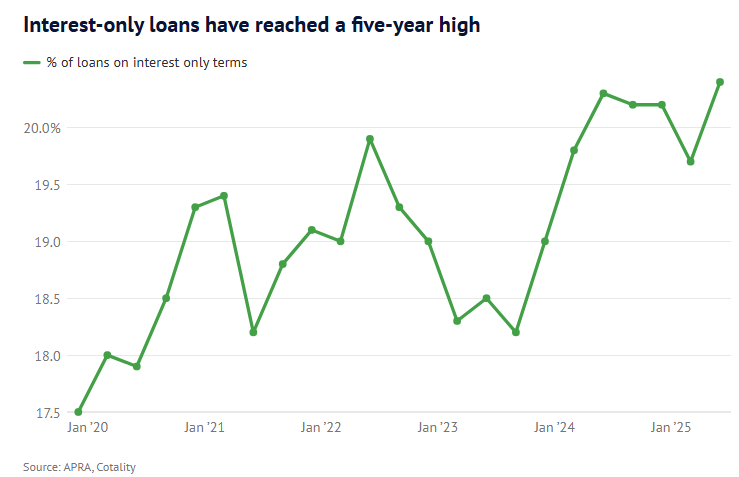

On Wednesday, Domain reported that interest-only lending for Australian home loans has hit a five-year high, driven by investors:

“One of the reasons for the increase is that 71% of these interest-only loans are going to investors, who accounted for 37.7% of new mortgages in the June quarter across the country”, noted Eliza Owen, head of research at Cotality Australia.

“Now that lending standards have been relaxed, we’ve seen a huge surge in investor and IO loans for the negative gearing benefits”, added Shane Oliver, chief economist at AMP. “But it does mean that people are getting into more debt and they’re not servicing that debt”.

The above developments suggest that Australia’s banks have free rein to pump mortgage demand, with financial regulators asleep at the wheel.

The overall Australian mortgage market is quickly turning sub-prime. Drastic regulatory action is required to rein it back in.