This week, I was interviewed by Steve Austin at ABC Radio Brisbane, where I was quizzed on why policymakers continually implement self-defeating policies that make housing more expensive.

Austin’s query followed this month’s introduction of the Albanese government’s 5% deposit scheme for first home buyers, which already seems to have lifted demand and pushed home prices higher.

During the recent federal election campaign, we also saw both sides explicitly state that they want to see Australian house prices rise at a ‘sustainable rate’ from already record-high levels.

This view about wanting to see house prices forever rise has been the status quo in Australia ever since former Prime Minister John Howard stated to Steve Austin in 2003 the following about house prices:

“Anybody who owns a house is very happy that the value of that house has gone up, let’s be quite straight about that. I haven’t found anybody in seven and a half years shake their fist at me and say Howard, I’m angry with you for letting the value of my house increase”.

Politicians in Australia have continually implemented self-defeating demand-side “affordability” measures that end up inflating home prices because of electoral maths: the number of homeowners (roughly two-thirds of the population) outnumbers the number of renters (roughly one-third).

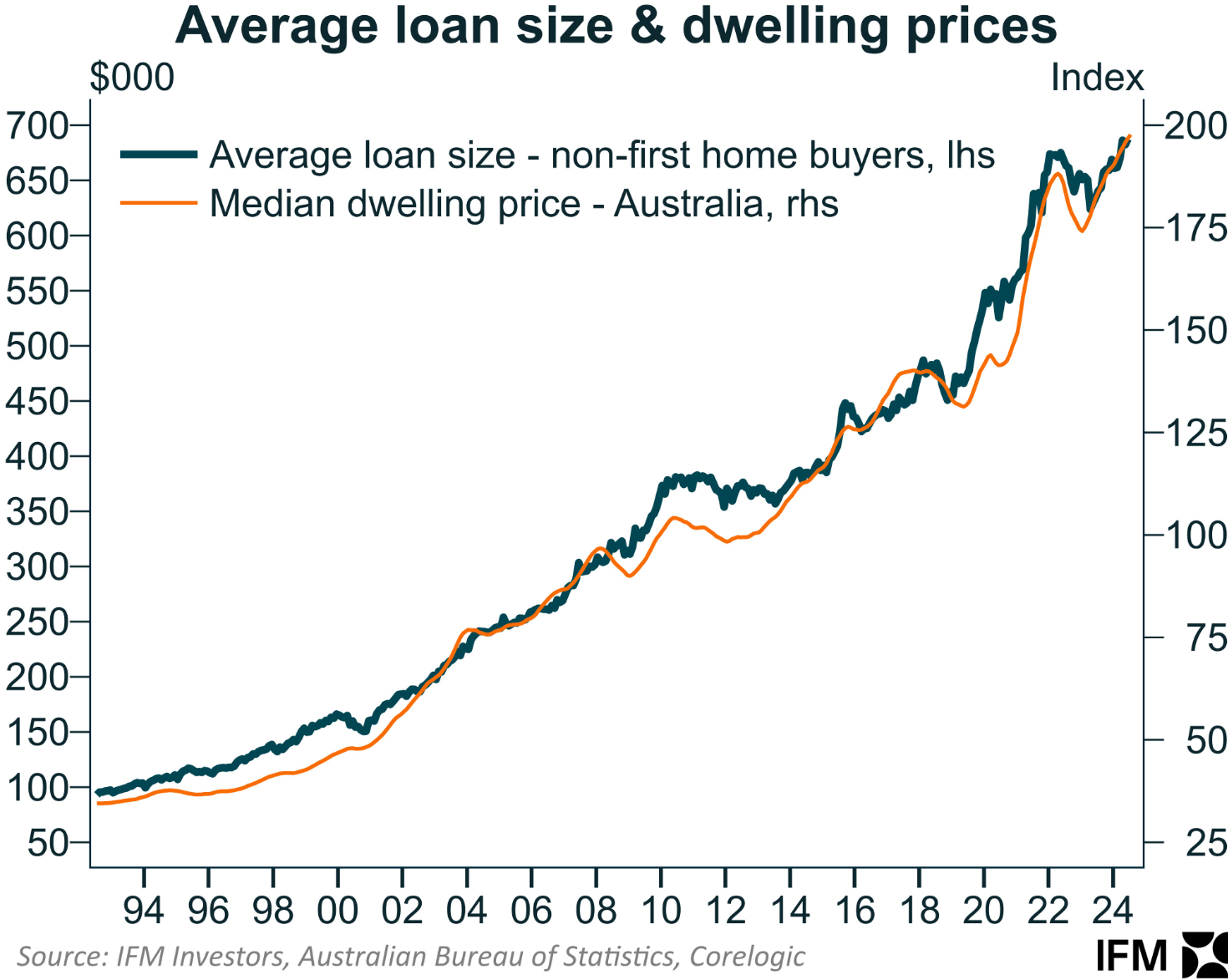

Such policies include first-home buyer grants, shared equity schemes, and now 5% deposit schemes. These types of policies always end up driving mortgage sizes and home prices higher.

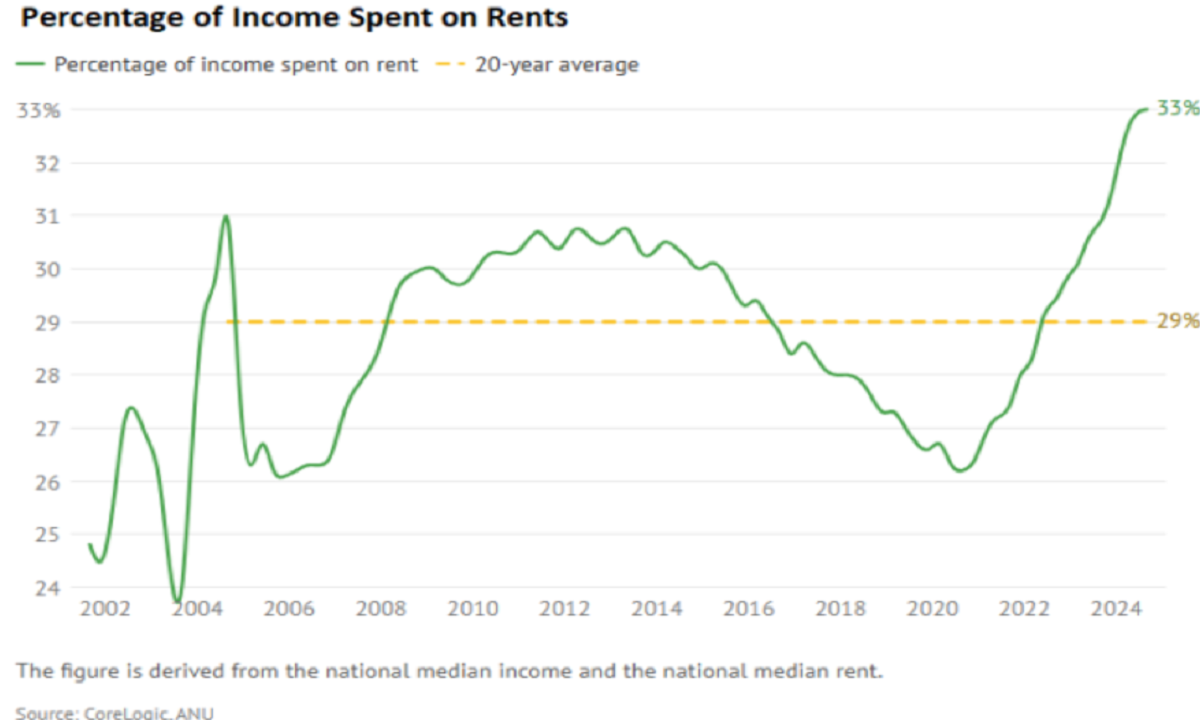

For 20 years, Australia has also run an excessively large immigration program, which has ensured that population demand forever outruns supply, although the impact of high immigration has been more detrimental to the rental market.

A side issue is that Australia’s federal politicians are some of the nation’s heaviest property investors.

A recent analysis by The Guardian revealed that “more than half the politicians in federal parliament have disclosed owning investment properties or multiple homes, with at least 50 receiving rental income as landlords”.

First-home buyers in Australia are being excluded from the market because prices are too high relative to earnings. They are also paying a record share of their incomes on rent while they save for a deposit.

The first solution, therefore, should be to reduce immigration, which is particularly detrimental to first-home buyers for two reasons.

- Excessive immigration increases the costs of renting, making it more difficult for prospective first-home buyers to save a deposit.

- Excessive immigration puts upward pressure on home prices, pushing ownership further out of reach.

However, with Home Affairs and Immigration Minister Tony Burke owning six residential properties, lowering immigration to sensible and sustainable levels would be against his (and other politicians’) financial interests.

The federal government should also limit investment property concessions, preferably as part of a fundamental reform of the tax system that shifts the burden away from workers through income taxes and towards other forms of taxation, such as resource, consumption, and wealth taxes.

However, restricting property tax concessions would also work against politicians’ financial interests.