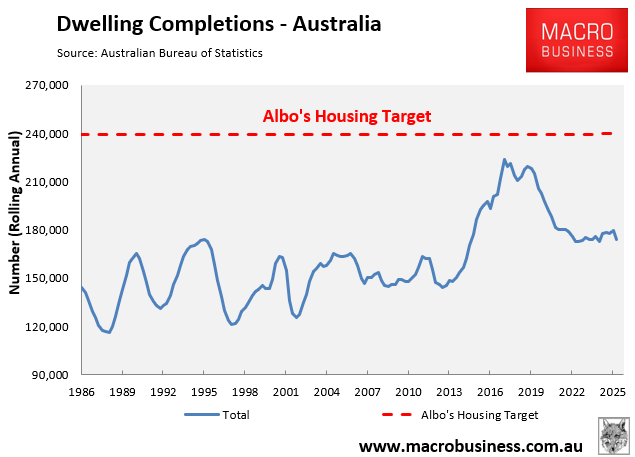

Last week’s dwelling completions data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) showed that in 2024-25, the Albanese government fell 65,970 (27%) behind the National Housing Accord’s target, which requires 240,000 homes to be built annually for five consecutive years.

It also means that Australia will have to build around 256,000 homes annually over the next four years to meet Labor’s 1.2 million target.

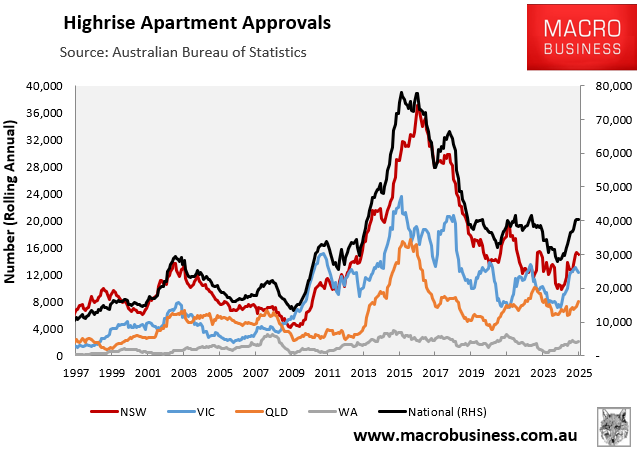

Achieving a record ramp-up in high-rise apartment construction is a prerequisite for meeting this target.

However, the latest high-rise approvals data from the ABS showed that approvals nationally were tracking 48% below last decade’s peak.

The problem with high-rise construction is multifaceted.

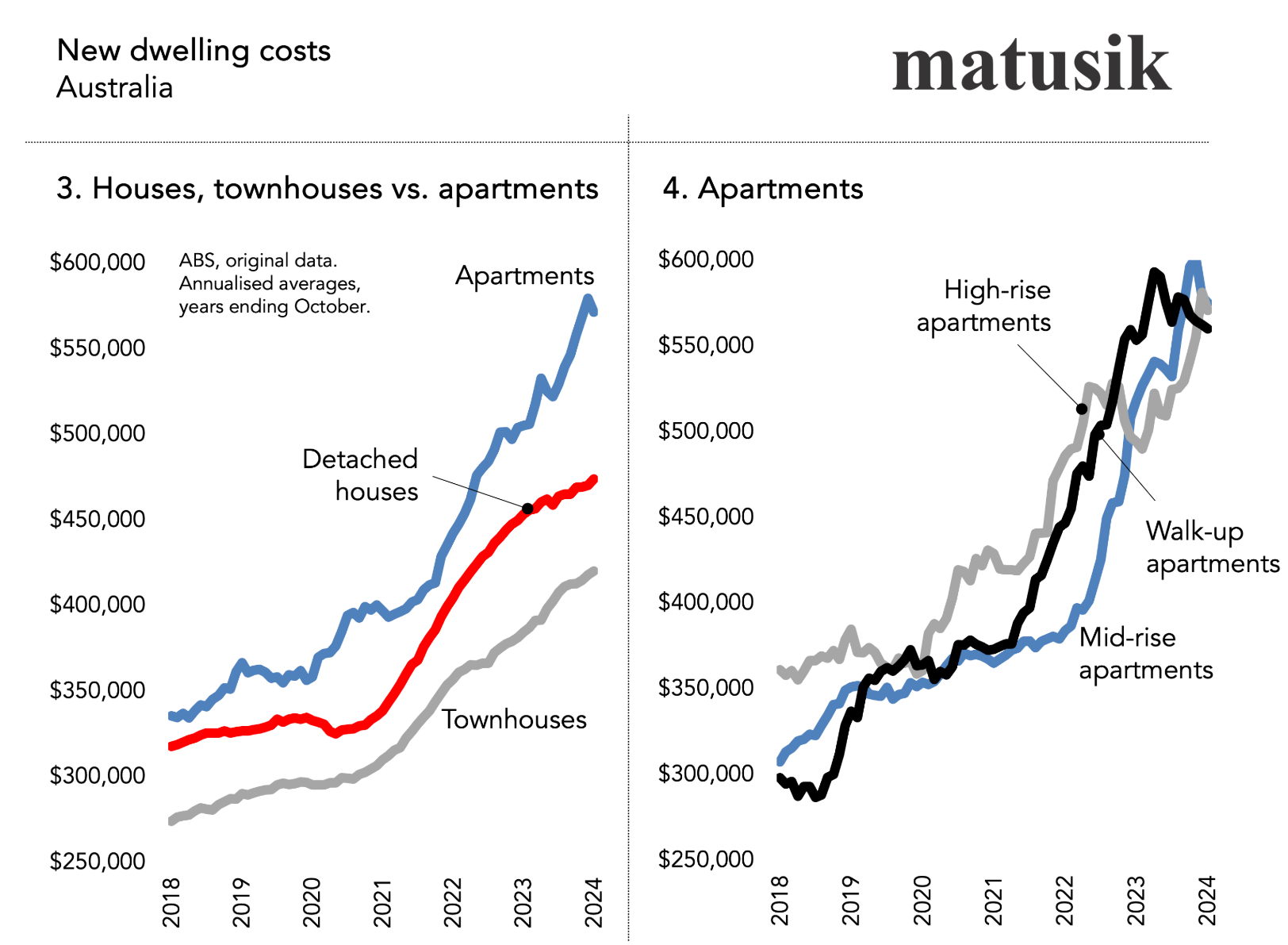

First, the cost of constructing apartments has ballooned since the pandemic, as illustrated below by Michael Matusik.

This surge in construction costs has priced many apartment projects above what consumers are willing to pay.

The construction quality of new apartment complexes in Australia is also poor, and strata fees are high, further limiting affordability.

The Age in May reported a glut of unsold apartments across Melbourne, with an estimated 8,000 completed apartments—comprising 17% of units completed between 2020 and 2024—sitting idle on developers’ books.

“These unsold apartments include those in suburbs earmarked for greater housing density under the state government’s activity centre proposal, raising concerns that the surplus could hinder developers from meeting ambitious housing targets”, The Age wrote.

Charter Keck Cramer’s national executive director, Richard Temlett, added that the unsold stock was significantly cheaper than the newest batch of apartments due to the rising construction costs.

The unsold apartments could be purchased for around $8000 to $10,000 per square metre, whereas apartments entering the market now need to be priced at $12,500 to $15,000 per square metre, according to Temlett.

“So it is a concern from the developers’ perspective because that stock needs to be removed from the market so it’s not competing with new stock on price point”, he said.

“It is a major issue because it’s holding back new supply, and housing is only going to get more unaffordable, and rents will increase more”.

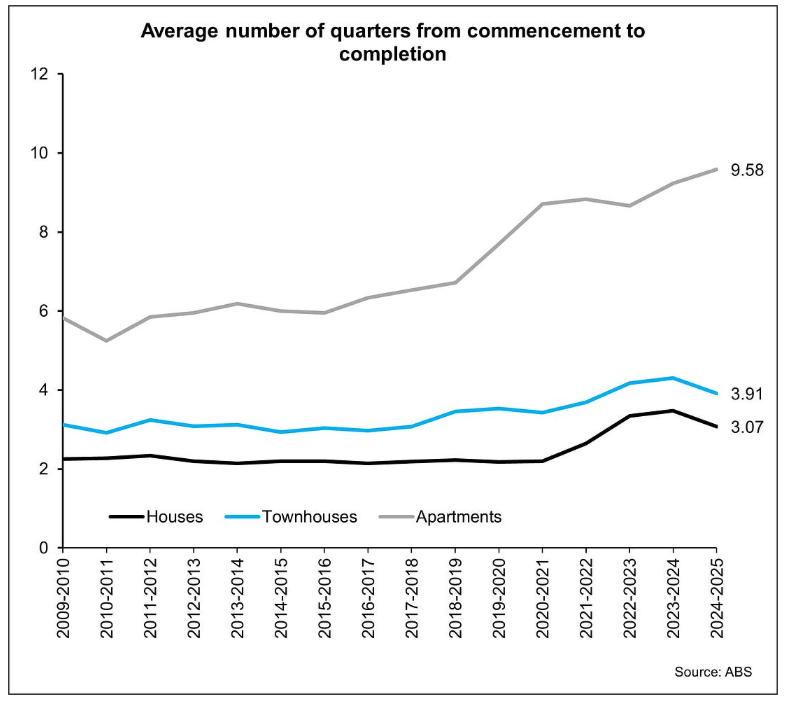

To add further insult to injury, Cameron Kusher from Oz Property Insights posted the following chart, derived from the latest ABS construction data, showing that the time taken to build apartment projects increased to a record 9.6 quarters, up around 50% from 2017, when Australia’s dwelling construction rate peaked.

Last week, Mirvac chief executive of development Stuart Penklis warned of a potential downturn in the Australian construction sector next year, led by high-rise apartments.

“The one thing that I’d call out, which is evident in Victoria at the moment, is that the major subcontractors that engage with us as builders are flagging a significant drop-off in workbook next year—a lot of government projects are completing and not a lot of new large-scale apartment projects coming out of the ground – [which] is a concern”, Penklis told Citi’s annual investment conference last week.

Penklis added that crews are already laying off staff.

None of the aforementioned developments bodes well for Australia’s housing targets, which are already significantly behind schedule.

If high-rise apartment construction does not accelerate and surpass the last decade’s boom, and Australia’s population continues to grow aggressively via immigration, then the housing shortage and rental crisis will inevitably worsen.

On the other hand, do we really want another boom in defective shoebox apartments? Cutting corners to quickly slap up apartments to meet the federal government’s high immigration policy was never in the nation’s interest.

Simply opting for a significantly smaller but higher-quality immigration program would solve Australia’s housing shortage and rental crisis.