The Guardian’s Luca Ittimani asks why state and local government plans to convert empty office buildings into apartments to ease the housing crisis have not come to fruition:

Momentum to create homes out of empty offices has faded even as office vacancies rise and housing shortages intensify.

Developers have not submitted a single application to turn an office into housing in central Melbourne since 2023. Just one successful application has been made in the CBD of Sydney, the country’s most unaffordable city.

Towers have proven expensive to refit and landlords have instead kept their properties in the office market, awaiting either a return of workers or government funding to make conversions stack up…

The Victorian government promised to help facilitate the conversion of the offices…

There are major impediments to converting an office tower into residential units, including:

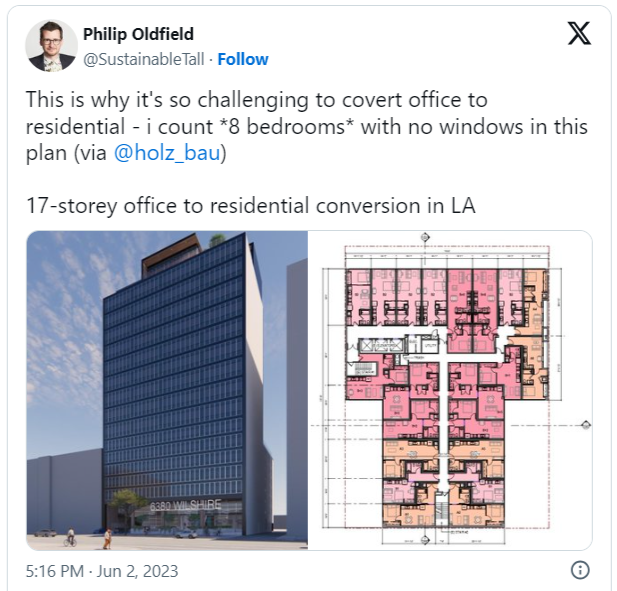

- Ensuring compliance with housing requirements for lighting, ventilation, and air conditioning.

- The conversion of an office’s large floor plans into individual dwellings. The larger the area of an office, the harder it is because of a lack of windows and natural light.

- Installing bathrooms and kitchens with water and sewage systems in new units.

- Trenching into floors to ensure sewage pipes have appropriate room without compromising the building’s structure.

Some office buildings are more suitable for conversion than others. The size and shape of the floor plans are the primary considerations.

In 2023, Professor Philip Oldfield, Head of the School of Built Environment at UNSW, tweeted the following on office-to-apartment conversions.

“Let’s say there’s 50 empty buildings in the Sydney CBD, maybe only five to 10 will be suitable to be converted to residential”, he said.

The heavy barriers confronting office-to-apartment conversions are explained in detail in the Search Engine episode: Why can’t we just turn the empty offices into apartments?

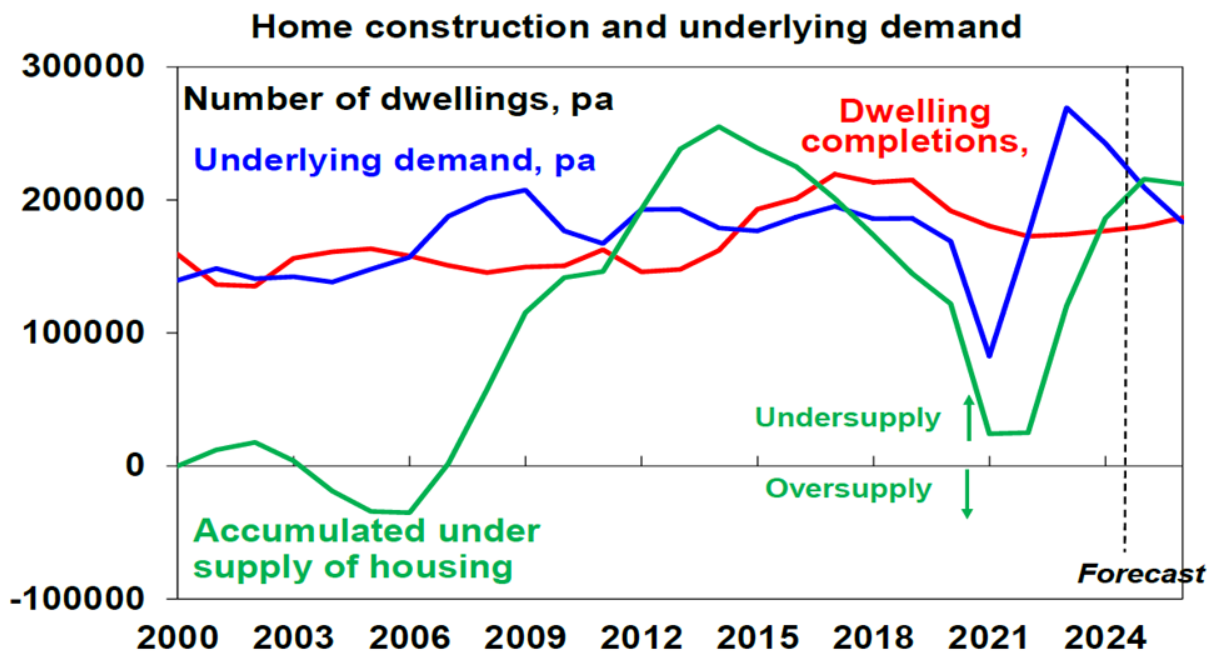

The primary solution to Australia’s housing shortage is to slow the rate of immigration to a level that enables Australia to catch up with its accumulated housing and infrastructure deficit, which is estimated by AMP chief economist Shane Oliver to be between 200,000 and 300,000 dwellings currently.

Source: Shane Oliver (AMP)

“Australian housing is chronically undersupplied”, Oliver wrote in July.

“This has been the case since the mid-2000s when immigration levels, and hence population growth, surged and the supply of new homes did not keep up. Our assessment is that the accumulated housing shortfall (the green line in the next chart) is around 200,000 dwellings at least and possibly 300,000 depending on what is assumed in terms of the number of people per household”.

“The economic reality is that when underlying population driven demand for housing exceeds its supply prices rise and that is what we have been seeing for the last twenty years”, Oliver wrote.

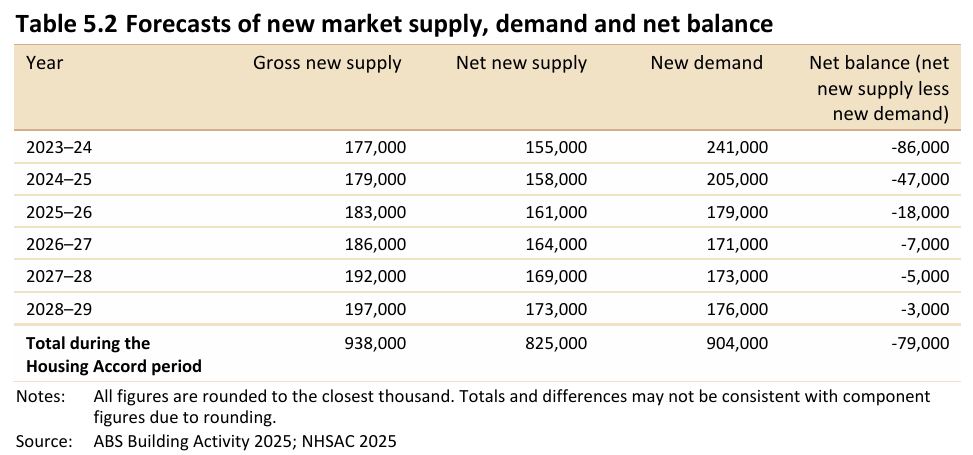

The federal government’s National Housing Supply and Affordability Council (NHSAC) likewise projected that the nation’s housing shortage will increase by 79,000 over the next five years as population growth continues to outrun new housing supply.

Policy gimmicks like converting office towers into residential apartment buildings won’t touch the sides and are a distraction from genuine solutions.