On Sunday, I appeared on Freya Leach’s Sky News show, Freya Fires Up, to debate Kos Samaris on the merits of Australia’s migration system.

The segment ended up being more of a polite discussion rather than a debate, given that we agreed on most things.

Nevertheless, a list of potential discussion topics was sent beforehand, which I have repurposed into Q&A form to explain the themes more clearly.

What do the numbers actually say about immigration levels in Australia?

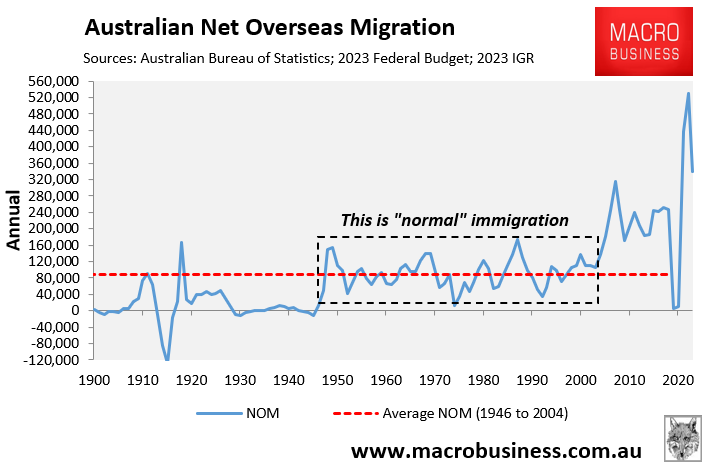

It is important to view the level of immigration from a historical context.

In the first 60 years after WW2, Australia’s net overseas migration averaged 90,000 per annum, with only two years over that period recording a NOM of more than 150,000.

In the 15 years of ‘Big Australia’ immigration leading up to the pandemic, NOM averaged 220,000 a year, an increase of 145% over the post-war average.

In the five years to the end of 2024, which includes the pandemic lockdowns, NOM averaged 260,000, a 190% increase on the post-war average.

The latest official net overseas migration numbers for Australia, which are current to the fourth quarter of 2024, showed that 340,000 net migrants landed over the year, which is higher than anything the nation had experienced prior to the pandemic.

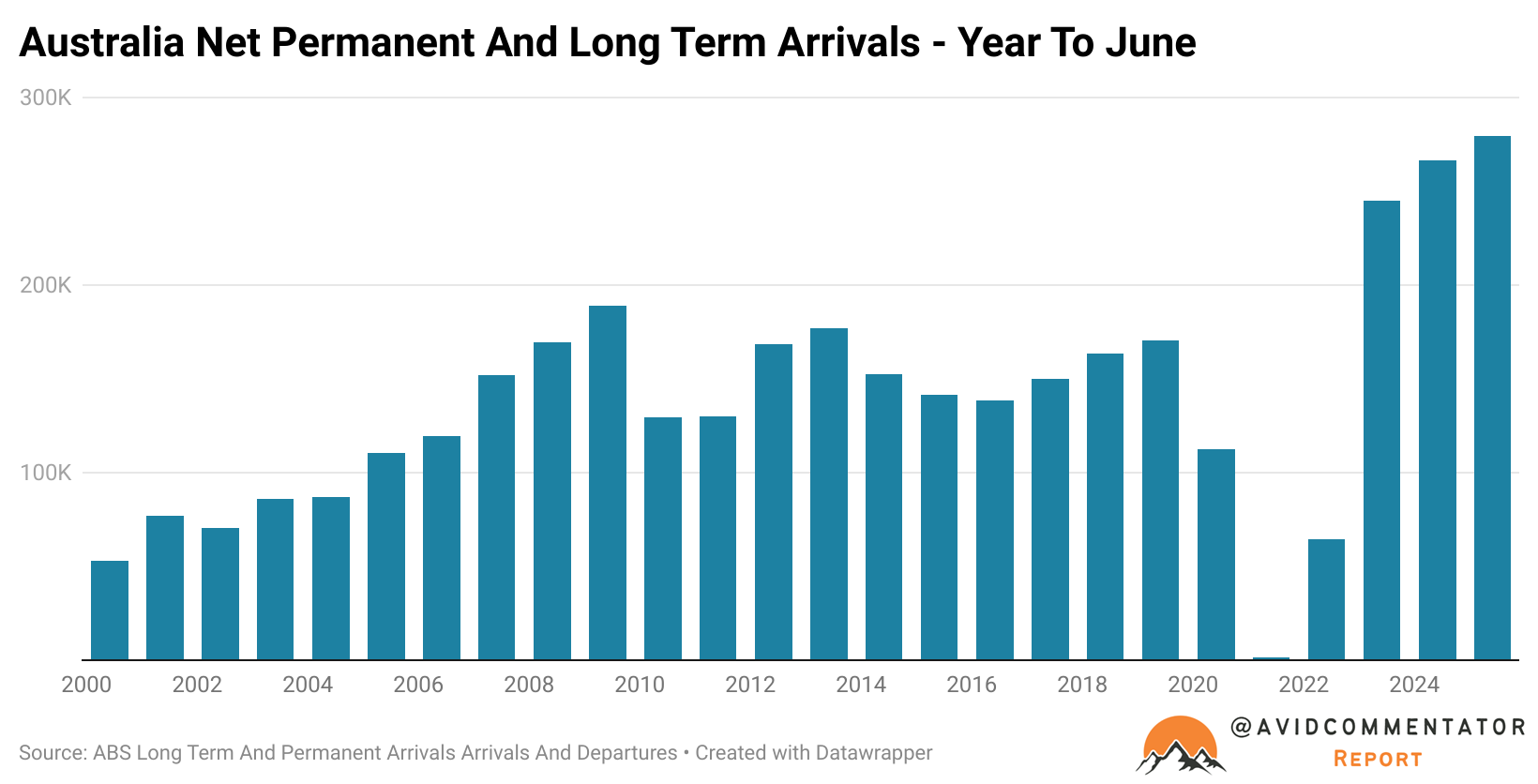

The ABS’ net permanent and long-term arrivals data, which has historically been a reliable leading indicator for net overseas migration, surged in the first six months of the year, suggesting that NOM has increased.

Is immigration too high?

Yes, immigration is too high for the simple reason that the population has grown much faster than the nation’s capacity to build housing and infrastructure.

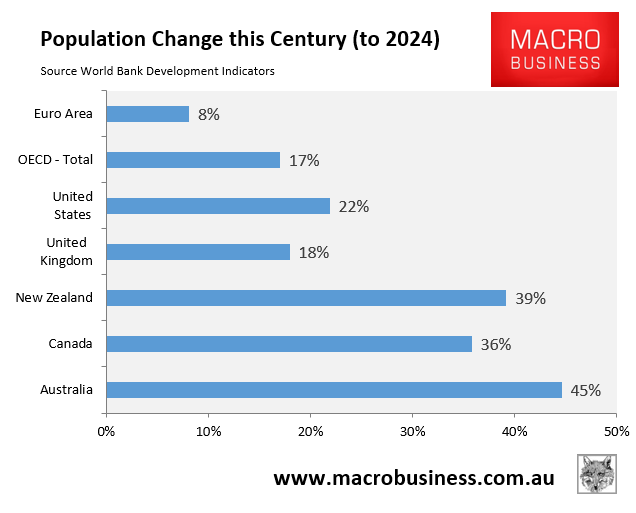

Australia’s population ballooned by 8.5 million (45%) in the first 25 years of this century, which is among the strongest growth in the advanced world.

Our major cities have ballooned in size, making them less liveable.

For example, it took Melbourne 165 years to reach a population of 3.5 million at the turn of the century. In just over 25 years, Melbourne has added about 2 million people, and it is officially projected to add another 3.5 million people in around 30 years.

Thus, if these projections come true, it means that in only around 55 years, Melbourne will have added 5.5 million people. This level of population growth is simply unsustainable and is eroding living standards.

What is the impact of immigration on the housing market?

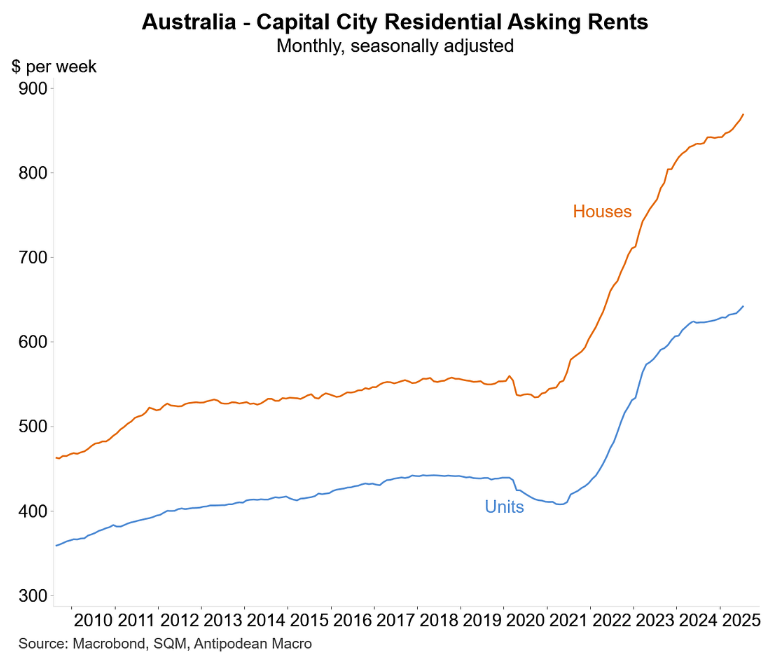

The biggest impact of immigration is on the rental market.

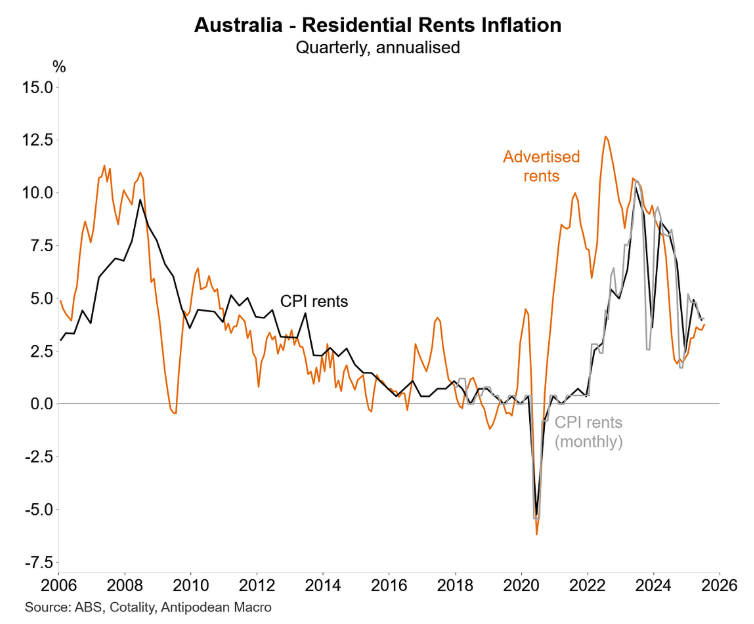

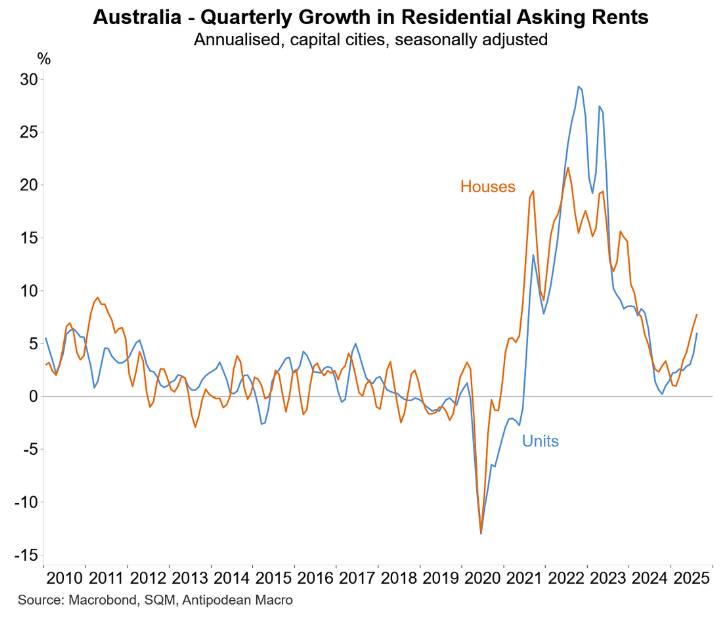

Rents fell at the beginning of the pandemic when migrants left, only to soar once record numbers of migrants rushed into Australia.

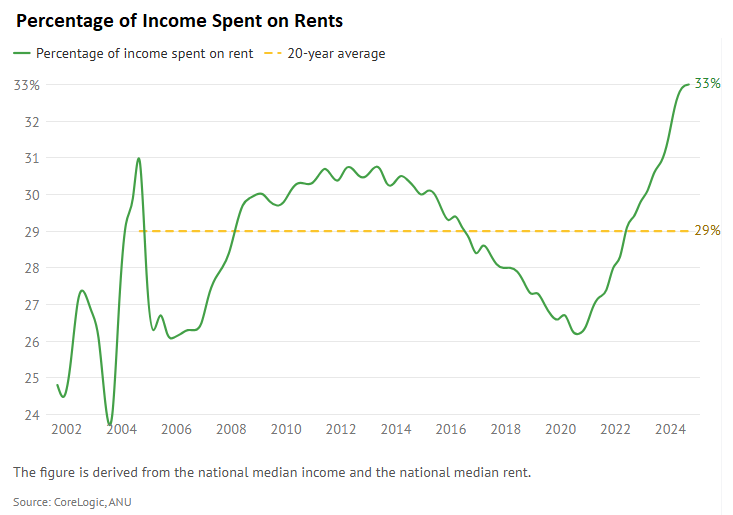

At the end of 2024, Cotality (formerly CoreLogic) estimated that rental affordability—as measured by the amount of median household income required to pay the median rent—hit a record low.

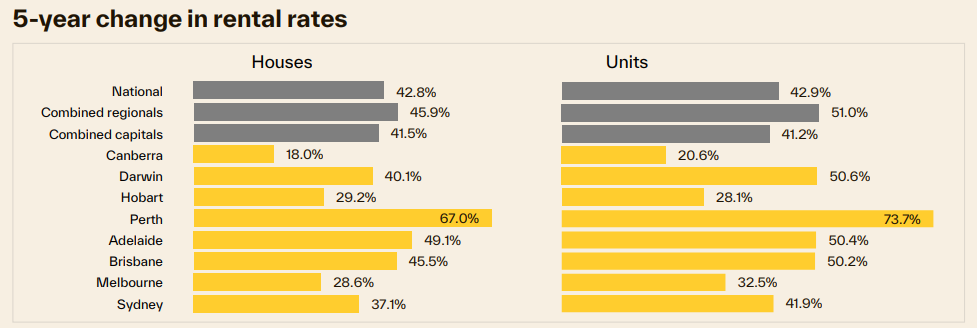

Cotality’s latest quarterly Rental Review, released in July, showed that rents nationally have ballooned by 43% over the past five years:

Source: Cotality

As a result, the national median weekly rent has risen by nearly $200 to $665 per week, adding $10,350 per year to the median rent.

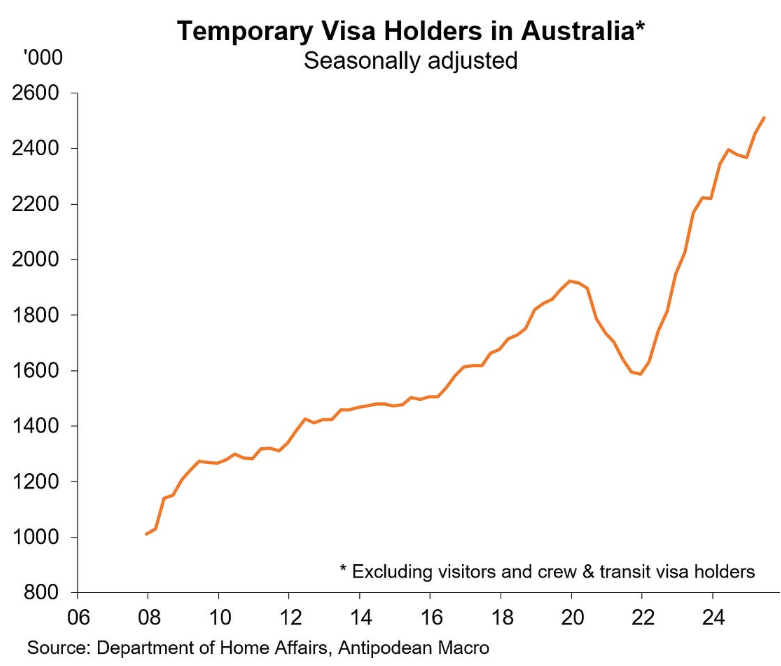

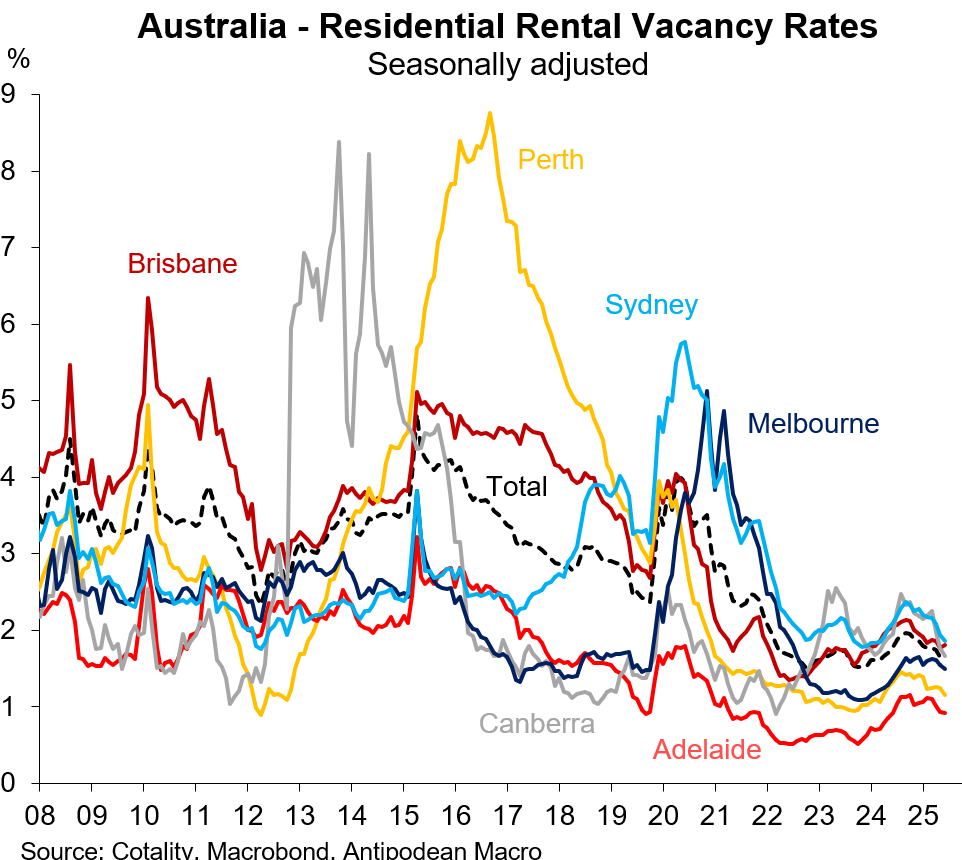

Now that net overseas migration seems to be rising again, the rental market has retightened.

Cotality reported that rental vacancy rates have fallen back to historic lows, with the national vacancy rate standing at just 1.5% nationally in August:

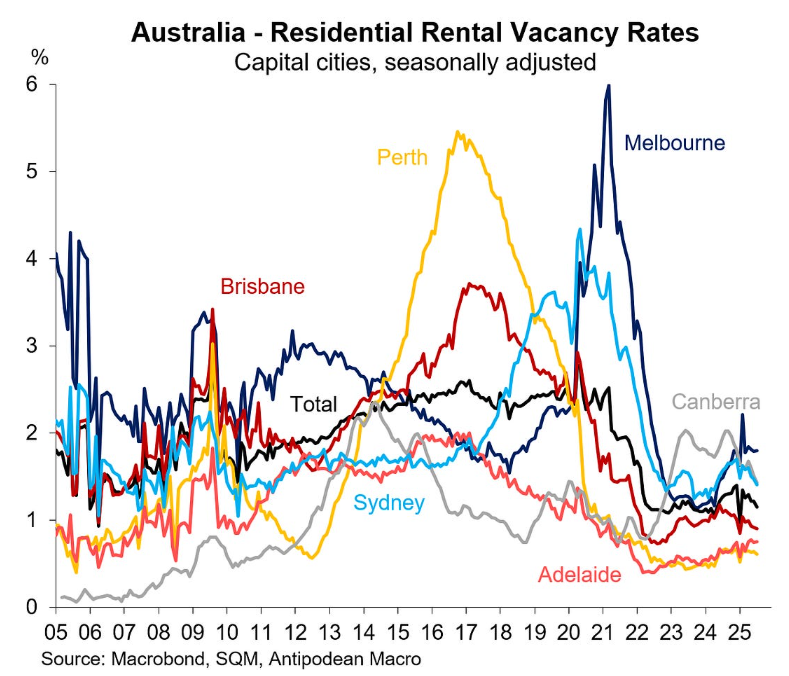

SQM Research data has also reported a decline in rental vacancy rates back to historic lows:

Meanwhile, both SQM Research and Cotality have reported a reacceleration in rental growth.

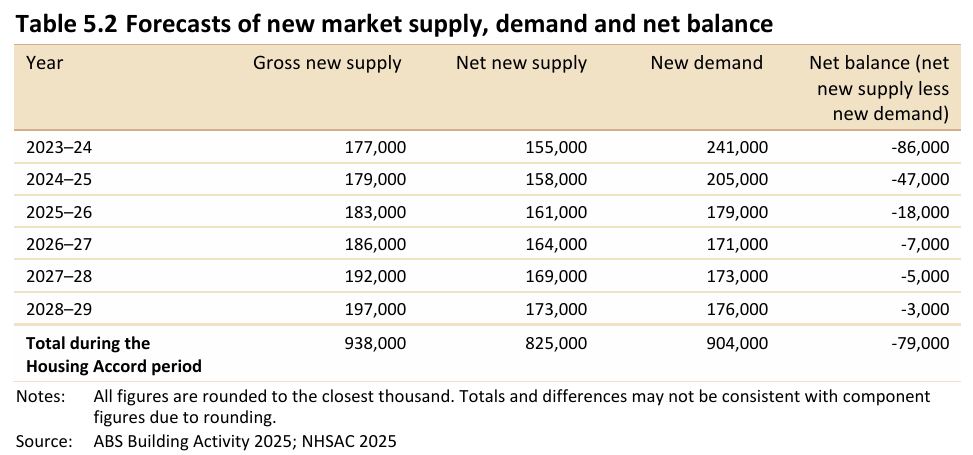

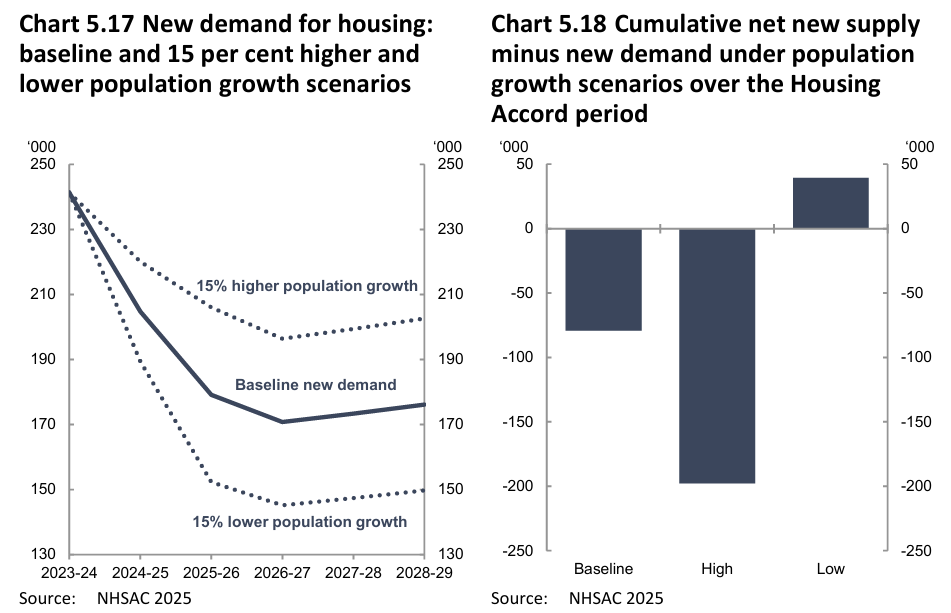

The National Housing Supply and Affordability Council (NHSAC) forecasts that new housing supply will remain below population demand over the five years to 2028–29, resulting in an additional cumulative undersupply of 79,000 homes.

NHSAC warned that ongoing strong immigration relative to supply will place upward pressure on rents and result in more homelessness and overcrowding.

NHSAC’s projections are likely conservative given that they are based on the Australian Treasury’s net overseas migration forecasts, which are expected to reduce to 255,000 per year in 2025-26 and then 225,000 across the remainder of the forecast period.

If Australia’s population grows 15% faster than projected, which seems likely given current immigration settings, then the projected housing shortage increases to around 200,000 over the next five years, according to NHSAC:

However, NSAC’s sensitivity analysis projected a surplus of 40,000 homes after five years if population growth is just 15% less than forecast.

NHSAC’s modelling shows that the primary solution to Australia’s housing shortage is to reduce net overseas migration to a level below the nation’s capacity to build housing and infrastructure.

Otherwise, the rental crisis will become permanent.

Big business often argues that we need more immigration to address skills shortages and increase demand in the economy. What is the impact on the economy from immigration?

Their argument is ‘whack’ a mole economics. Australia’s population ballooned by 8.5 million people in the first 25 years of this century—among the fastest growth in the advanced world—yet the economy continues to experience chronic skills shortages. This tells you that high immigration doesn’t work to solve skills shortages.

There are two dimensions to this problem.

First, most migrants work in unskilled roles or in areas unrelated to their area of skills.

Second, importing migrants to solve a skills shortage in one area increases shortages in others.

At a macroeconomic level, more immigration means a bigger economy and stronger aggregate GDP growth. However, it is per capita living standards that matter.

There is no use growing the pie through high immigration if everybody’s slice of the pie shrinks.

What do Australians think about immigration? Are anti-immigration rallies effective at shifting public opinion?

Virtually every opinion poll over the past decade-plus shows that Australians do not support high immigration nor the rapid growth in the nation’s population.

I would have liked to see the anti-immigration rallies pitched as sustainable immigration rallies. I would also have liked to have seen the migrant communities included, since they are often the ones that are most harmed by excessive immigration.

For example, it is migrant communities like those in Western Sydney and Western Melbourne, which are straining most from high population growth, that are suffering the greatest infrastructure shortages and are seeing their living standards eroded.

What is the path forward? What level of immigration would you like to see?

I would like to see Australia’s net overseas migration cut to around 120,000 a year—i.e., early 2000s levels—and focused on high skills.

Australia needs to prioritise quality over quantity. Doing so would lift productivity growth and relieve housing, infrastructure, and environmental strains.

I would also like to see a plebiscite at the next federal election seeking views about how large they want Australia to become. The government can then use the results of this plebiscite to set migration policy and achieve the desired population size.