This month’s Australian Financial Review property summit contained the usual bluster on the need to lift Australia’s housing supply to meet demand.

NSW planning minister Paul Scully accused anti-development residents in wealthy suburbs of NIMBYism and trying to lock future generations out of housing.

Mike Zorbas, chief executive of the Property Council of Australia, heaped praise on governments for facing off with NIMBYs.

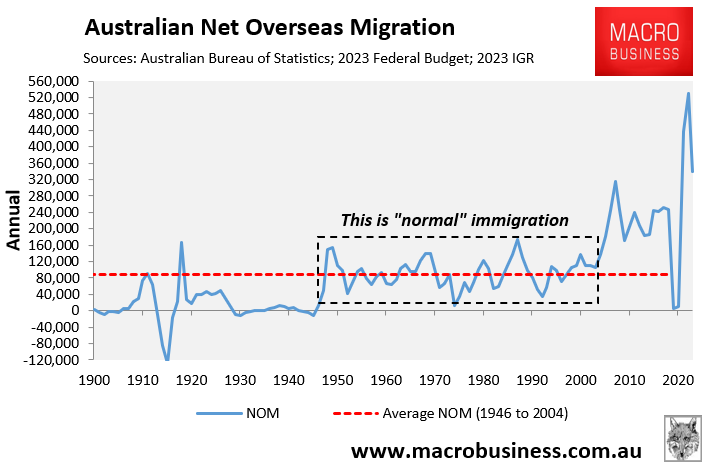

Developer Nigel Slathery called for more skilled migrants to work in construction, ignoring the fact that immigration is already at historic highs.

As usual, there was no acknowledgement that the fundamental reason why Australia has a housing shortage is due to excessive levels of immigration.

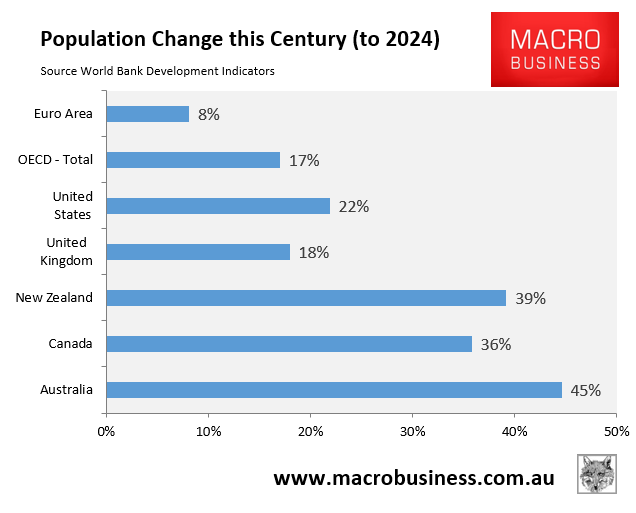

Australia’s population ballooned by 8.5 million (45%) in the first 25 years of this century, the fastest growth in the advanced world.

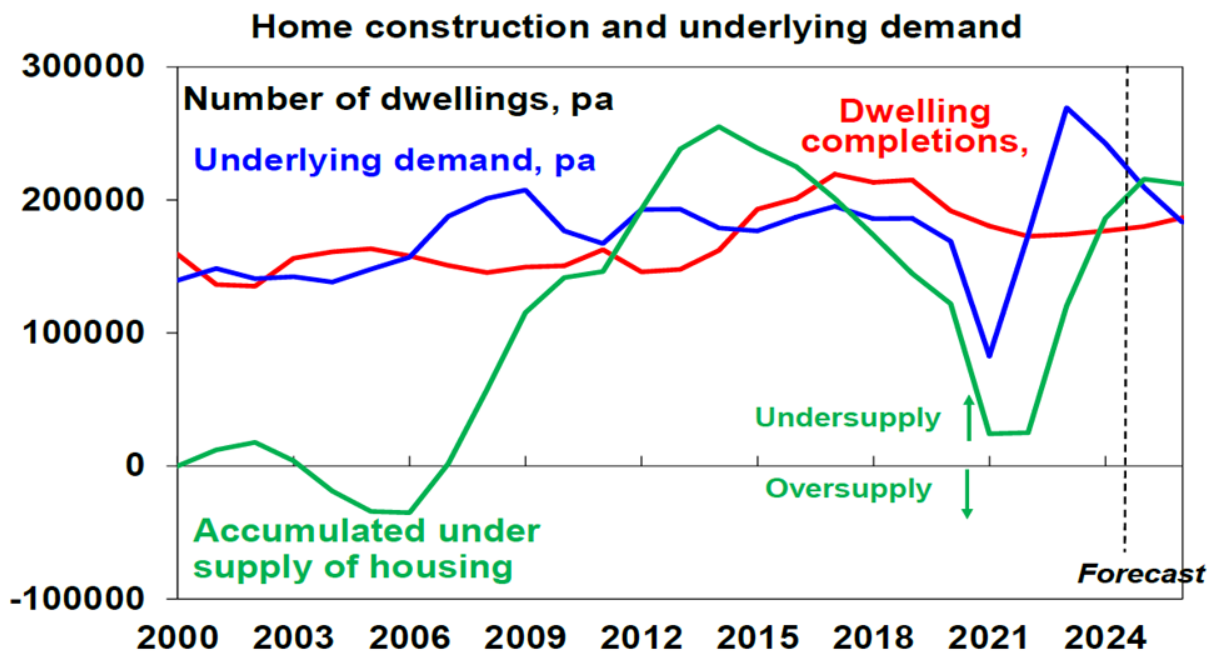

Chief economist at AMP, Shane Oliver, recently estimated that Australia has a cumulative housing shortage of between 200,000 and 300,000 homes, which he blamed on excessive levels of immigration above the nation’s capacity to build homes.

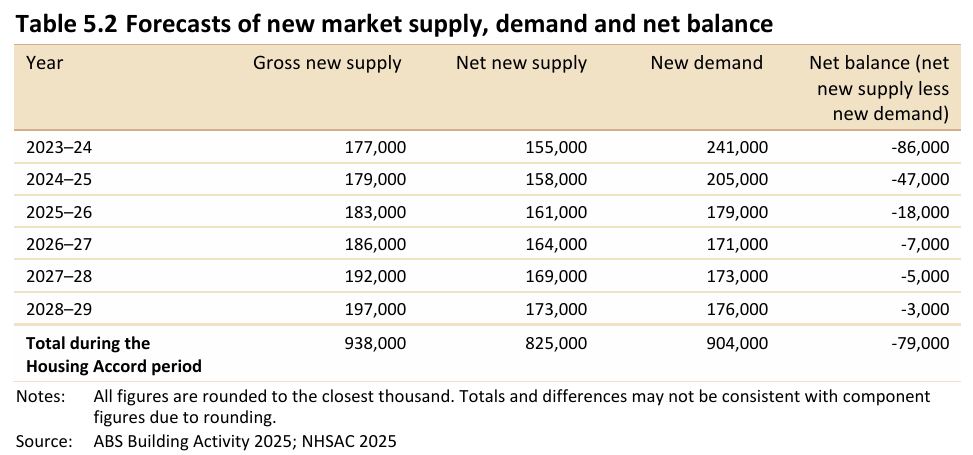

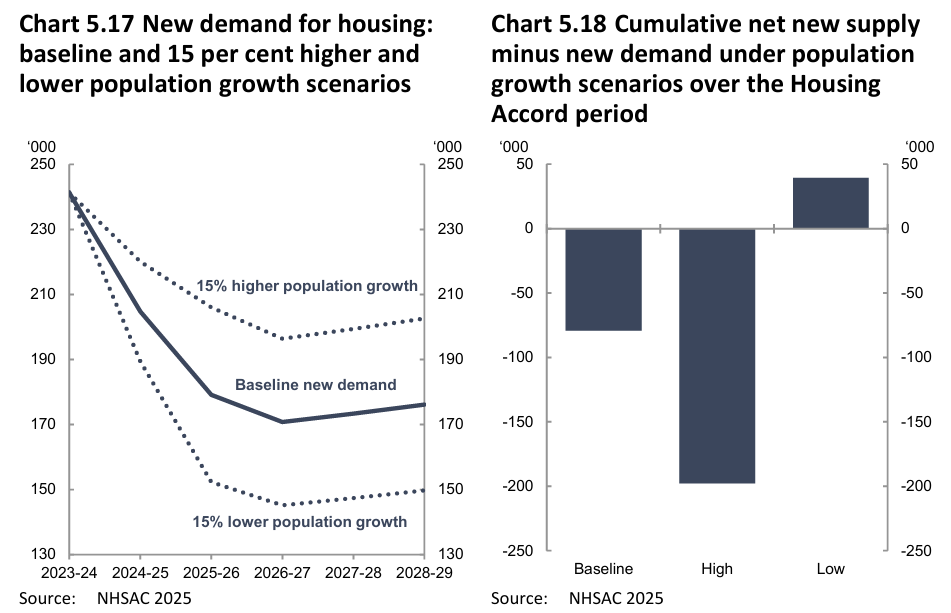

The federal government’s National Housing Supply and Affordability Council (NHSAC) projected that the nation’s housing shortage will increase by 79,000 over the next five years as population growth continues to outrun new housing supply.

As a result, Australia’s housing shortage and rental crisis will continue to worsen so long as the federal government persists in running a high immigration policy.

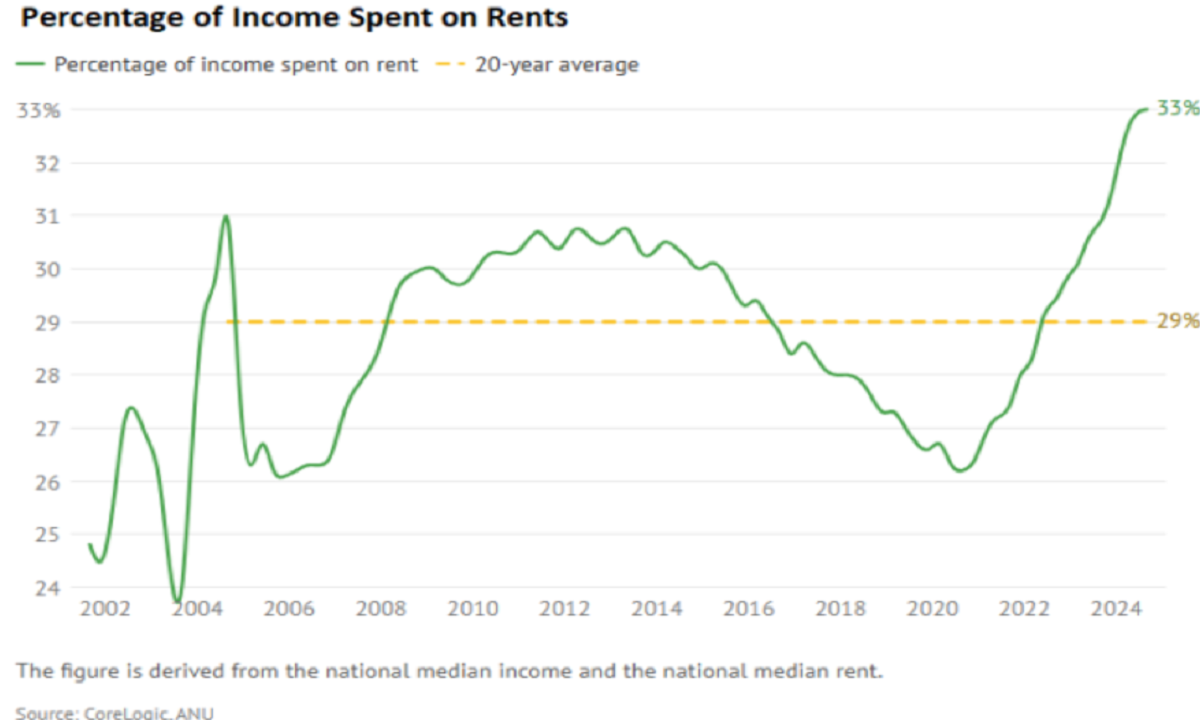

Australia’s renters are suffering:

Cotality (now CoreLogic) estimated that rental payments were chewing up a record 33% share of household income at the end of last year.

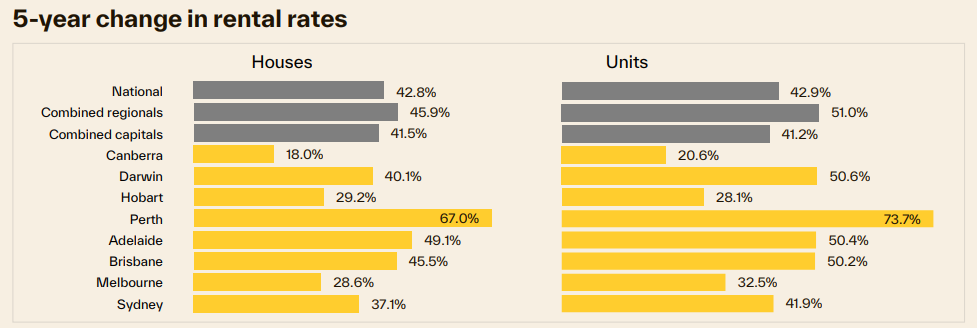

Cotality’s June quarter Rental Review estimated that weekly rents nationally have risen by $200 (43%) over the past five years, meaning that the median Australian tenant is now paying an extra $10,350 per year to rent the median home.

Source: Cotality

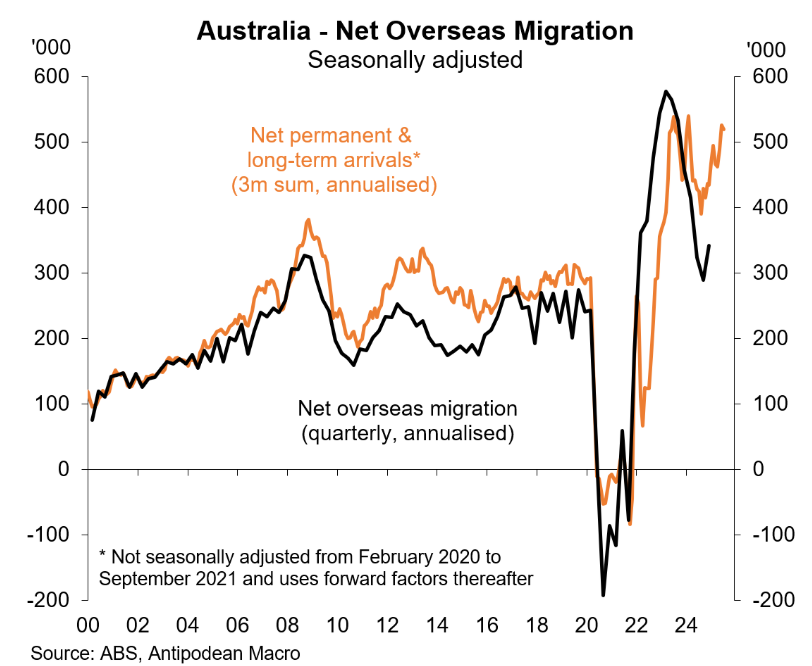

The driver of the surge in rents has been the post-pandemic surge in immigration, which saw an unprecedented 1.1 million net migrants land in Australia in the 30 months between June 2022 and the end of 2024.

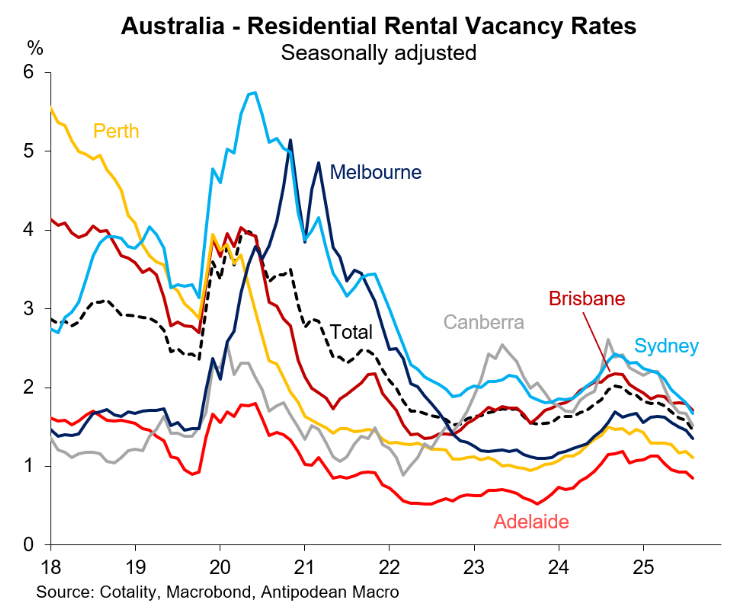

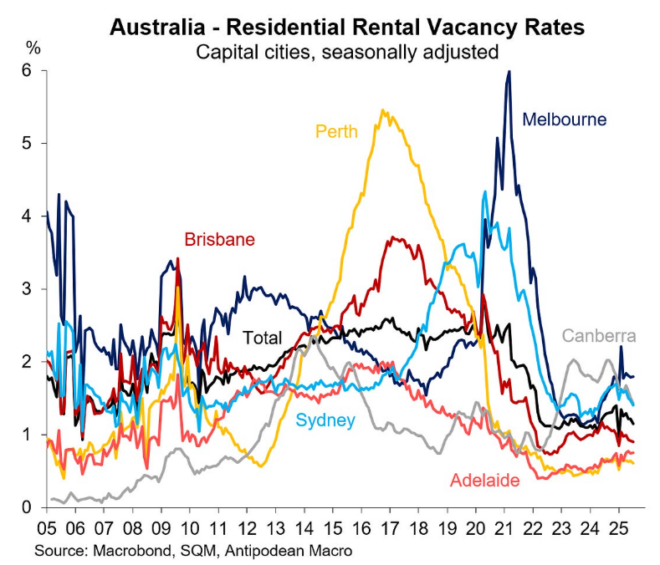

This surge in immigration sent rental vacancy rates to record lows and drove rents through the roof.

Last year, net overseas migration fell from its recent record high, from a peak of around 550,000 in 2023 to 340,000 in 2024, and it seemed that the rental crisis was finally easing. Rental vacancy rates began to rise, in part due to rising household sizes, and rental growth slowed.

However, in 2025, the rental crisis has worsened once more.

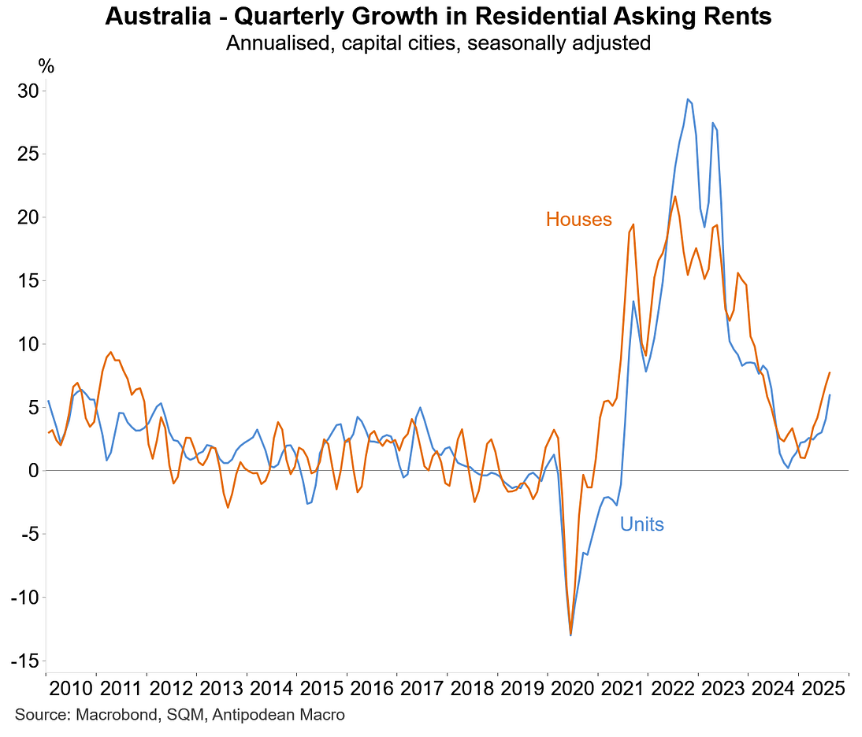

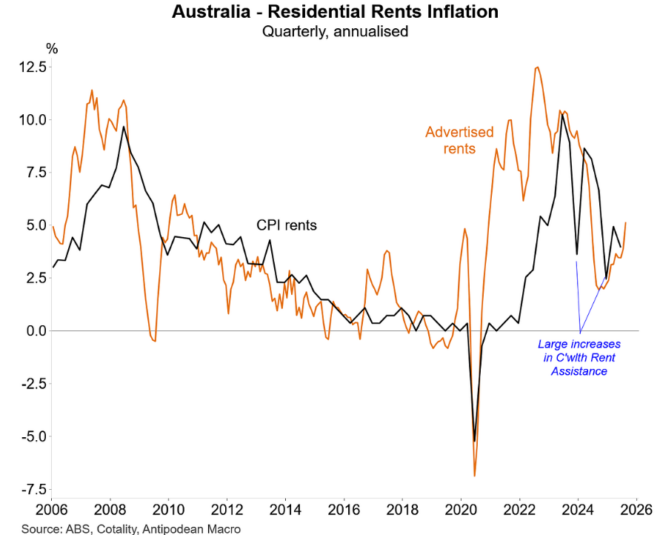

As illustrated below by Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro, rental vacancy rates, as measured by Cotality and SQM Research, have retightened this year back to the record low levels recorded in 2023.

Cotality and SQM Research have also recorded a sharp pick up in rental growth.

The deterioration of the rental market appears to have been driven by a rebound net overseas migration.

The monthly net permanent and long-term (NPLT) arrivals data was released by the ABS last week, which showed that there were a record 348,400 net permanent and long-term arrivals in the first seven months of 2025, up 15,300 (4.6%) from the 333,200 net arrivals that landed last year and 125,400 (56.2%) higher than the same period in 2019, before the pandemic.

The monthly NPLT arrivals series has historically closely tracked the official quarterly net overseas migration (NOM) series, which runs on a six-to-nine-month delay. The upswing over the first seven months of 2025 suggests that immigration into Australia has rebounded.

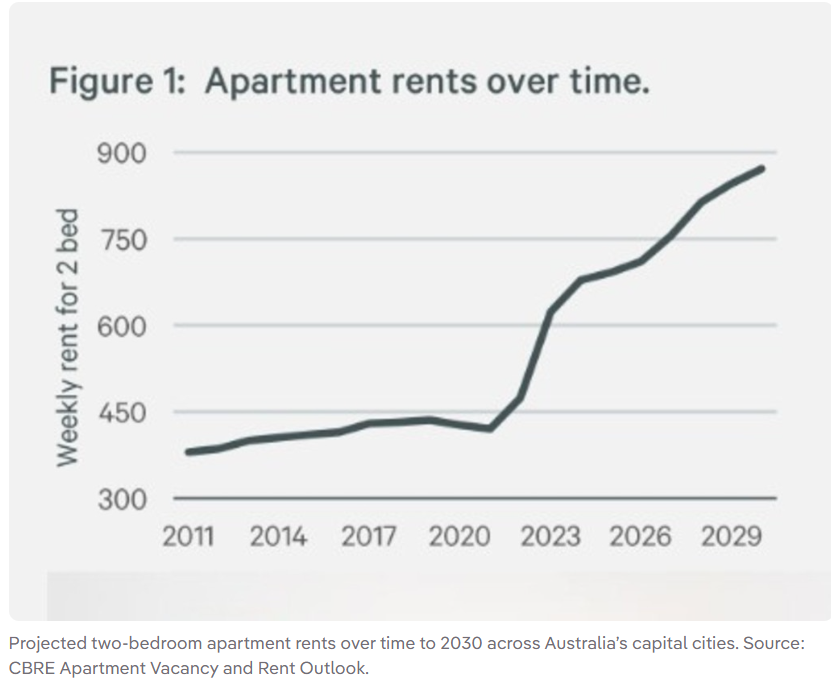

CBRE’s latest Apartment Vacancy and Rent Outlook, released last week, forecast that population demand will continue to exceed supply over the next five years. As a result, the national capital city vacancy rate is projected by CBRE fall to a record low of 1.1% by 2030, down from 1.8% in 2025.

As a result, 92% of two-bedroom apartments across the capital cities will have rents exceeding $700 per week by 2030.

In other words, Australian renters are facing more pain as the rental crisis continues to worsen.

Canada provides the solution to the rental crisis:

While the property industry, politicians, and the media continue to blame a lack of supply for Australia’s rental crisis, Canada has provided the obvious solution: cutting immigration.

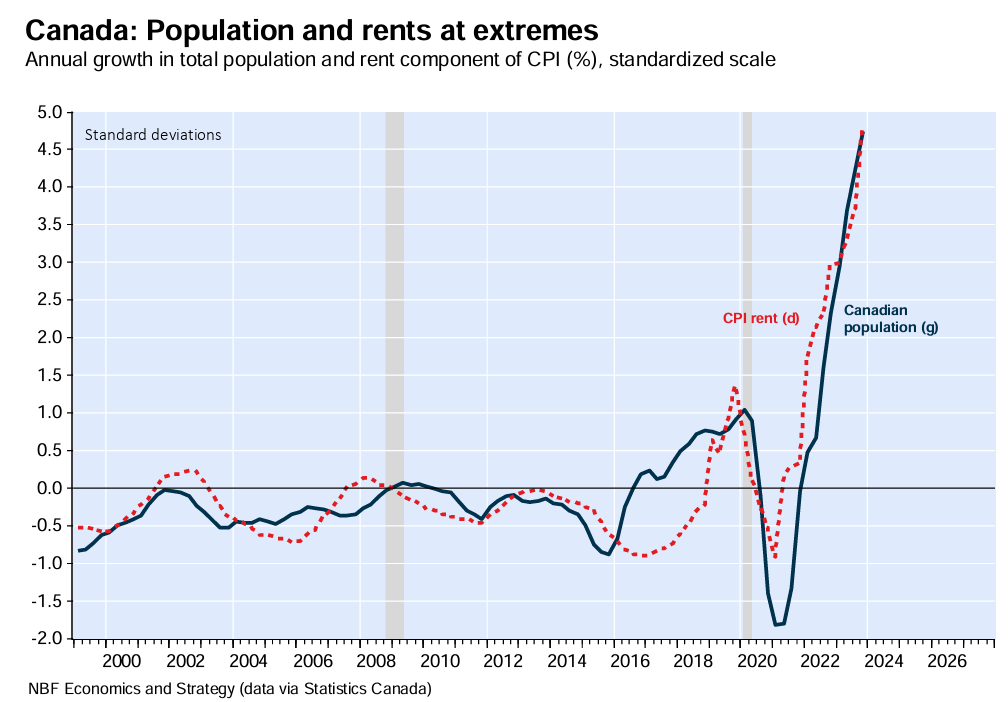

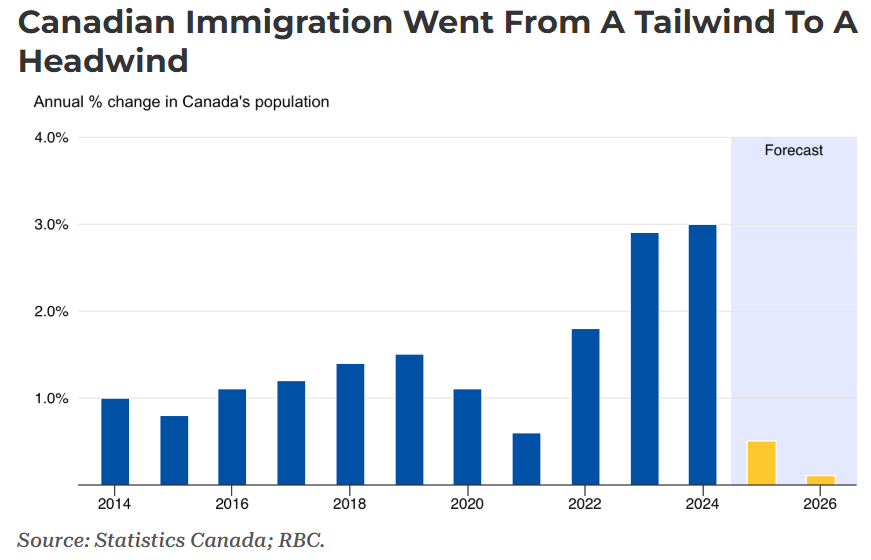

Like in Australia, rents in Canada soared to a record high in 2022 and 2023 in response to the country’s largest immigration influx in history.

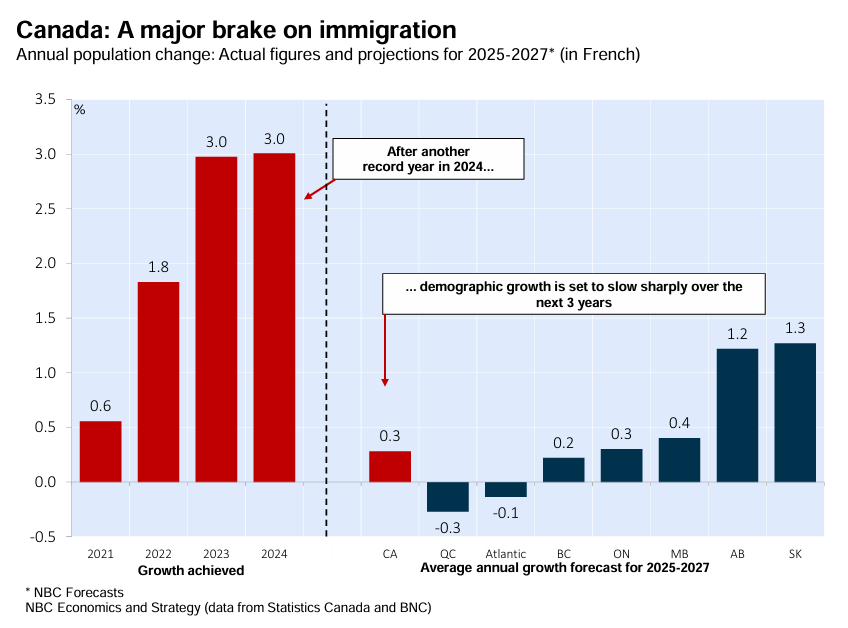

Last year, the Canadian government imposed a three-year pause on population growth to relieve the strains on housing and infrastructure.

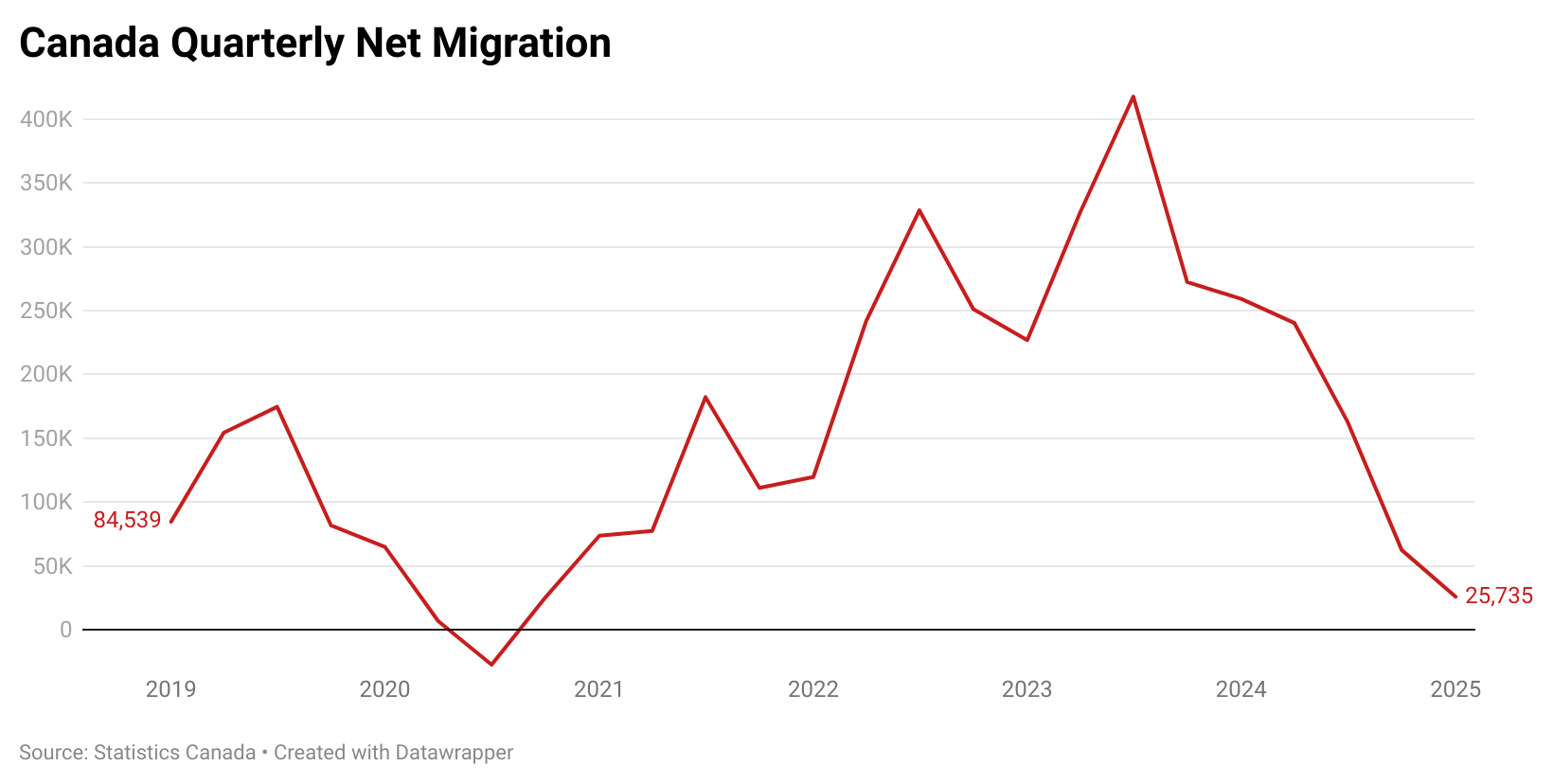

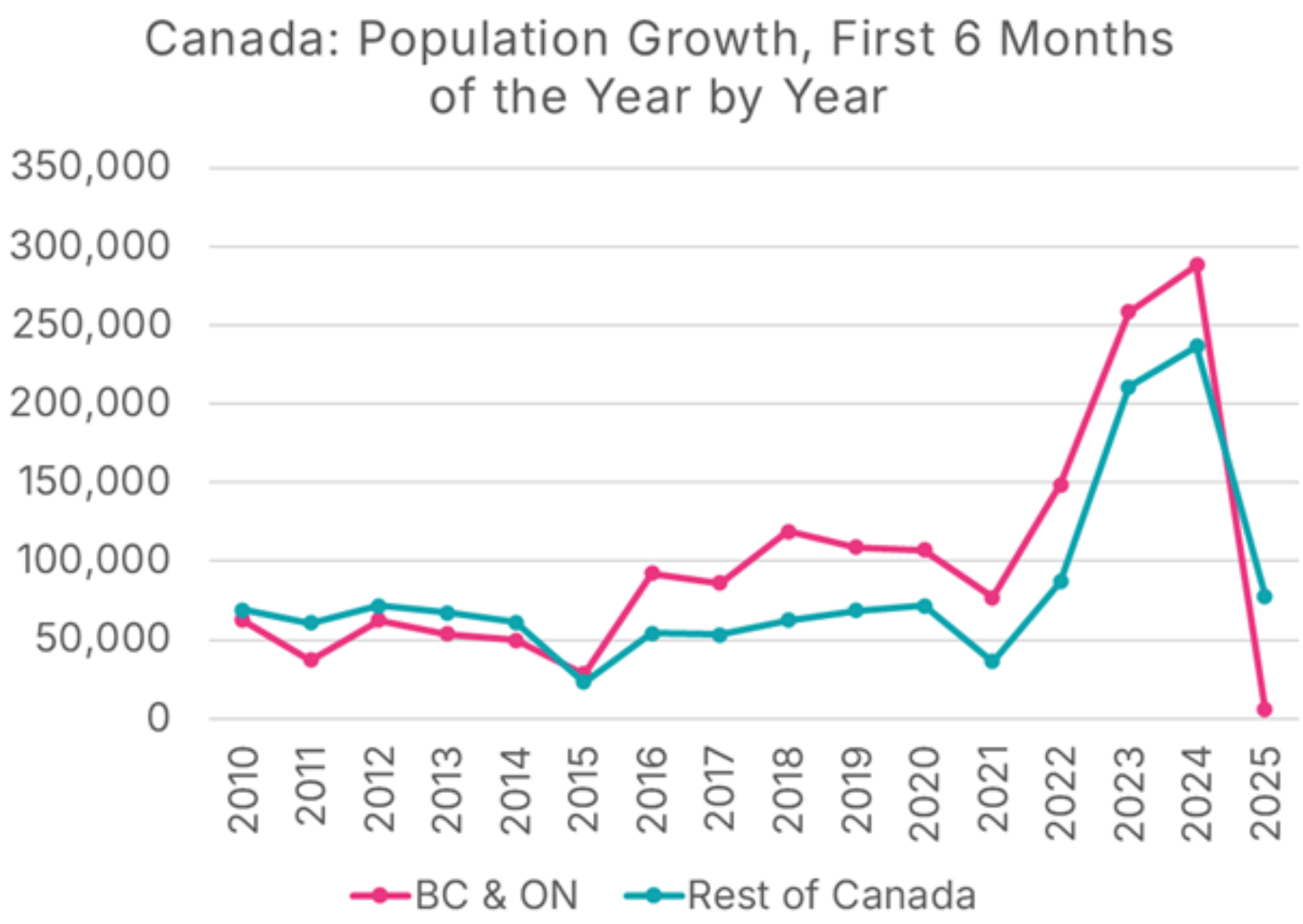

The plan has worked. Lots of temporary migrants have left Canada.

Canada’s net migration has decreased by more than 90% from its peak in 2023. Net migration has plummeted by more than two-thirds since its final pre-pandemic reading in the same quarter.

The sharp decline in immigration and population growth has driven rents down across Canada.

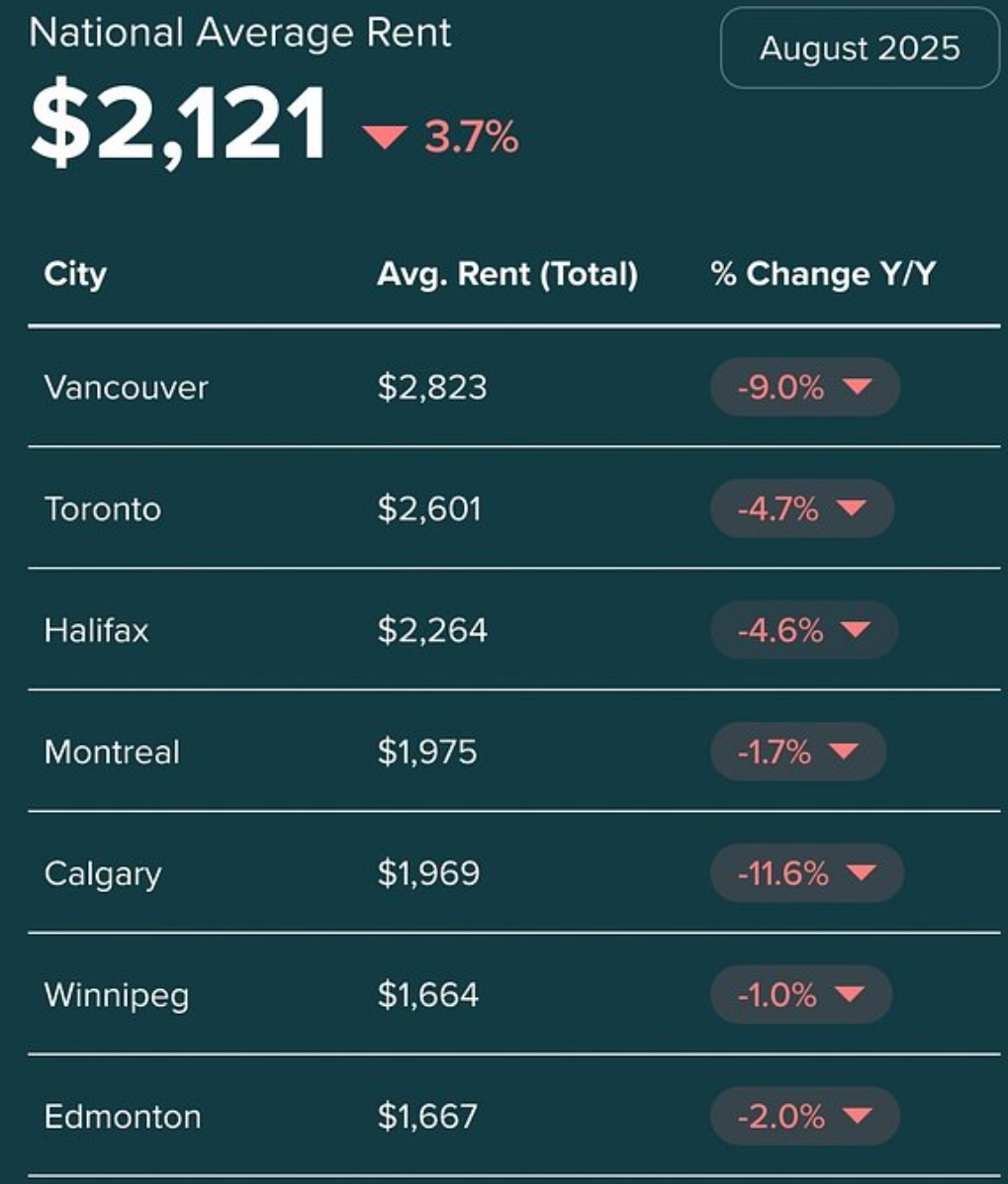

The latest National Rent Report from Rentals.ca and Urbanation shows that asking rents in Canada fell for 11th consecutive month in August, led by Vancouver and Toronto, which have experienced the biggest declines in population growth.

Canada’s largest bank BMO also stated last month that rents should continue to fall as “stricter immigration targets continue to slow population growth and limit new household formations”.

BMO also noted that immigration has transformed from a “tailwind to headwind for the housing market”.

Interestingly, the NSAC’s sensitivity analysis projected a surplus of 40,000 homes after five years, instead of a shortage of 79,000, if population growth is just 15% less than forecast by the government.

Policymakers should follow Canada’s lead and significantly reduce immigration to address Australia’s housing crisis.

I discussed these issues in my weekend Treasury of Common Sense with Luke Grant at Radio 2GB/4BC.