Australia’s migration system is flooding the nation with low-skilled workers.

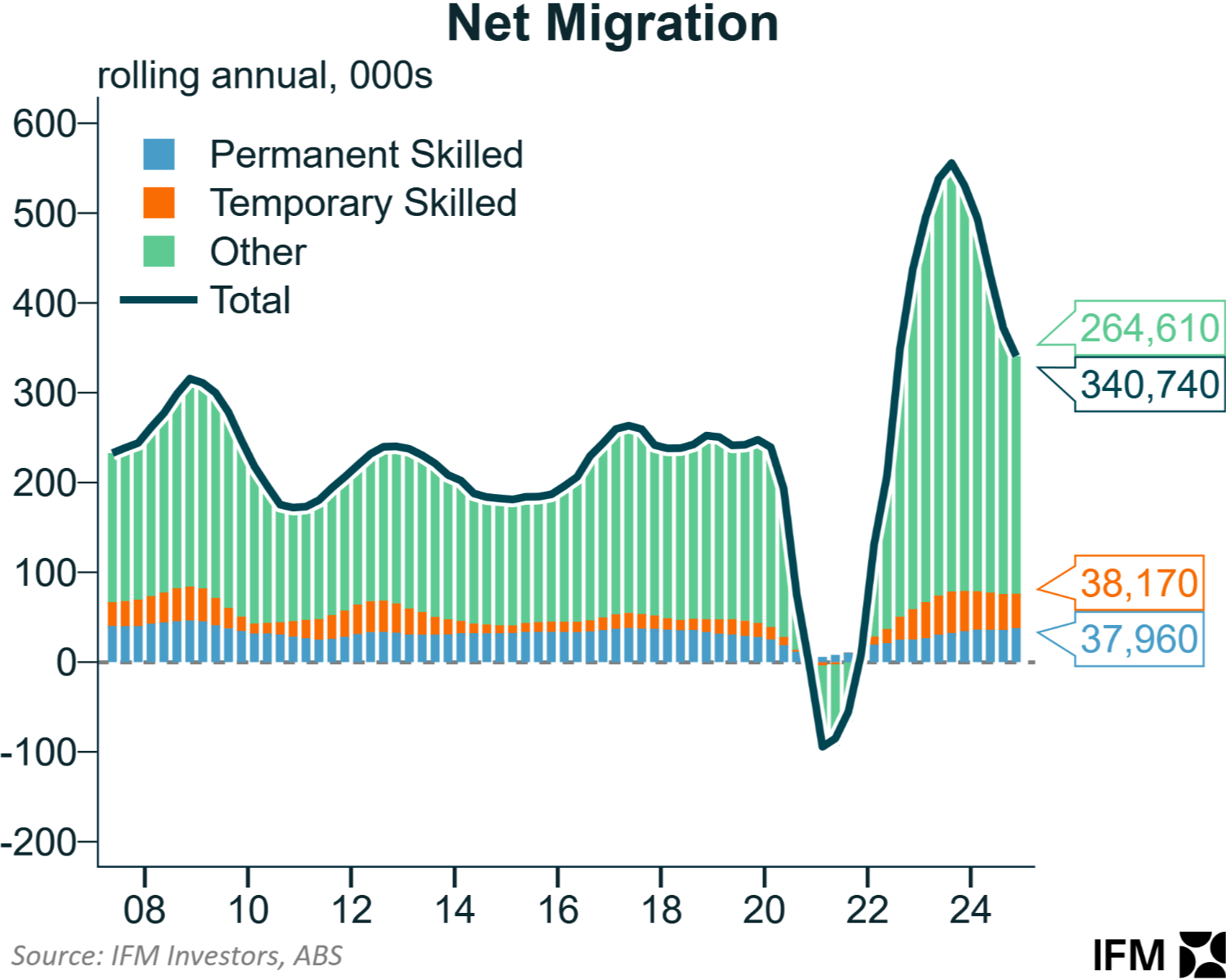

The following chart from Alex Joiner at IFM Investors summarises the situation, with the overwhelming majority of net migrant arrivals arriving through pathways other than skilled visas:

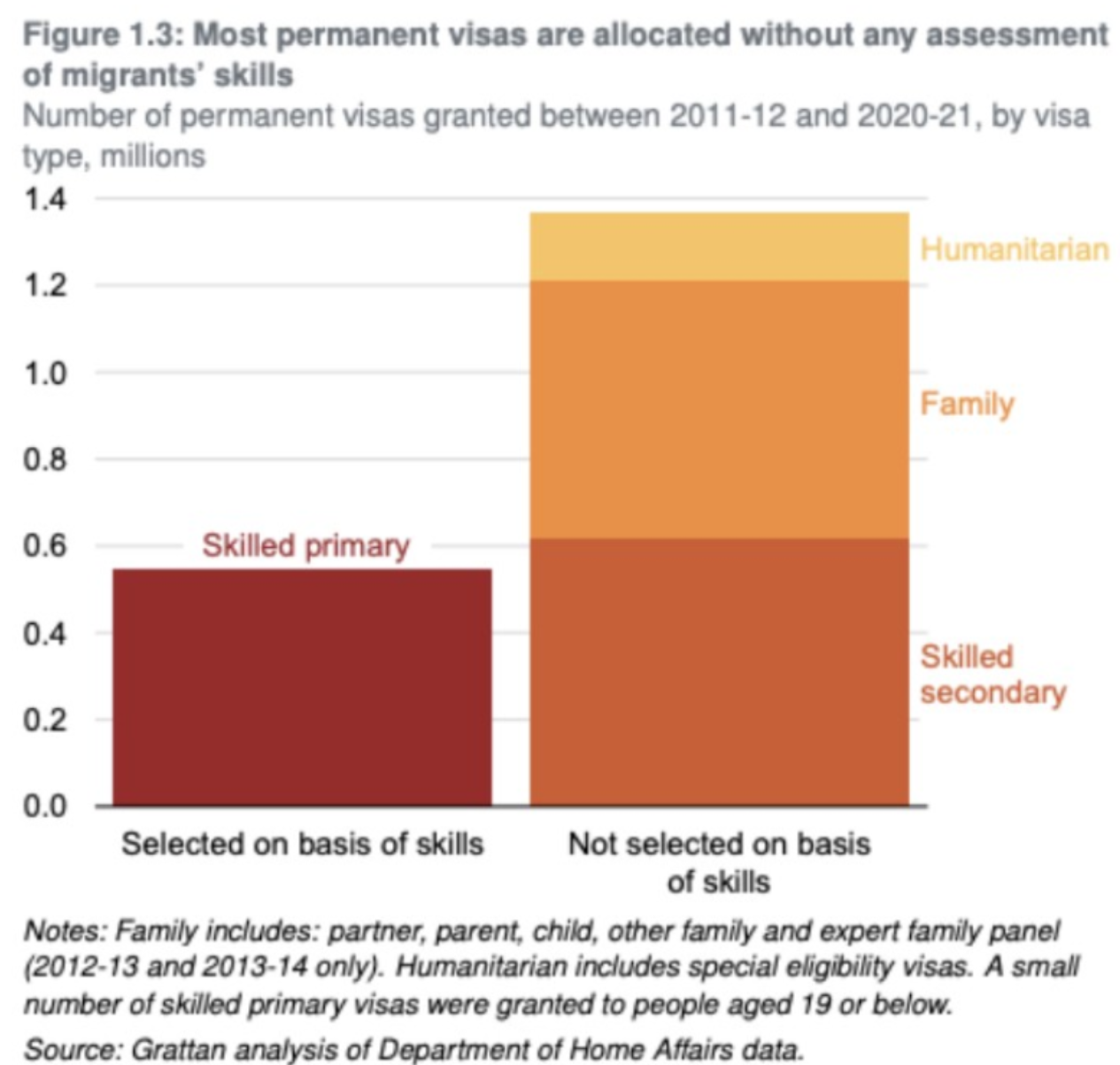

Even leading pro-Big Australia shills Peter McDonald and Alan Gamlen admitted that Australia’s permanent migration system is unskilled and broken.

“Australia’s migration programme has failed to deliver what it promises”, the authors say in their report.

“It brings in relatively few genuinely skilled workers, while favouring family migration. It delivers few new skilled workers while being clogged with family visas”.

The following chart from the Grattan Institute shows similar outcomes:

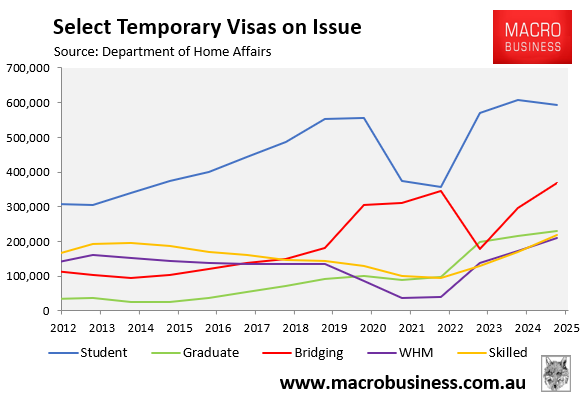

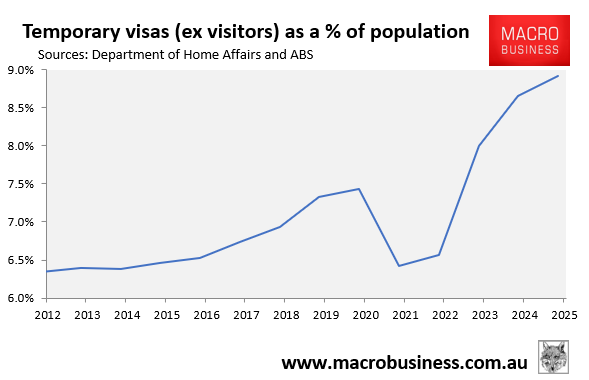

Similar concerns can be raised about Australia’s temporary visa system, which has swelled to nearly 2.5 million people in the June quarter of 2025. The overwhelming majority of these visas are unskilled or have purportedly skilled workers in low-skilled roles.

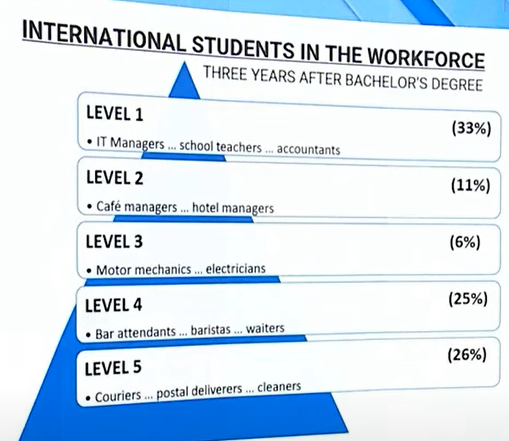

For example, the federal government’s 2023 Migration Review found that 51% of overseas-born university graduates with bachelor’s degrees were employed in unskilled jobs three years after graduation.

Source: Migration Review, 2023.

University of Sydney Associate Professor Salvatore Babones, who authored the 2021 book Australia’s Universities: Can They Reform?, highlighted the skills problem last month in The AFR:

Contrary to popular perceptions, most immigration to Australia is not high-skilled permanent migration. Most immigrants are here on working holiday and student visas.

Working holiday visa grants alone now outnumber skilled migrant visas granted each year…

Working holiday makers can now stay for up to three years, and the new “work and holiday” visa is open to young people from China, India, Brazil, Thailand and other developing countries.

These visas maintain the charade that their recipients are coming for “an extended holiday in Australia”. That is to say, a holiday spent working in a kitchen, delivering food, or providing aged care.

But the true behemoth is the student visa program. There are roughly a million international students in Australia, only half of whom actually study at universities. The rest attend cooking schools, hospitality schools, language schools, and other non-degree institutions.

An additional 200,000 are in Australia on post-study “temporary graduate” work visas.

All told, foreign youngsters now make up more than 10% of Australia’s total labour force – and they’re not working high-skill, high-productivity jobs. Anyone living in a capital city who has ever taken an Uber, ordered Uber Eats, visited a restaurant, hired a removalist, needed home care, or driven past a lollipop girl knows the truth.

As illustrated below by Alex Joiner from IFM Investors, the latest data on recruitment difficulties from Jobs and Skills Australia (JSA) suggests that the nation is awash with low-skilled workers.

As you can see, employers are finding it easier to fill lower-skilled roles than at any time since the pandemic.

The Albanese government last month announced that it has raised the planning level for international students by 25,000 to 295,000 for 2026.

Labor also watered down some English-language test requirements.

As a result, Australia’s international student and temporary visa numbers—which are already the highest in the advanced world relative to our population—will inevitably increase.

The data is clear that Australia is importing giant volumes of people with the wrong skills, which is adding to housing and infrastructure strains and delivering lower productivity growth.

Australia needs to run a significantly smaller migration system focused on quality over quantity and importing genuine skills that the nation actually needs.