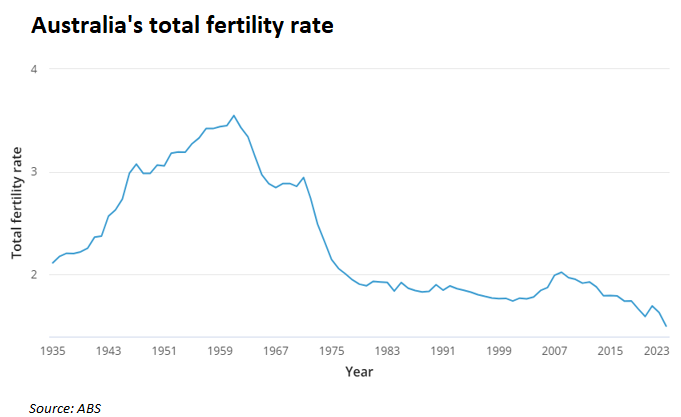

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), the nation’s total fertility rate fell to a record low of 1.50 babies per woman in 2023.

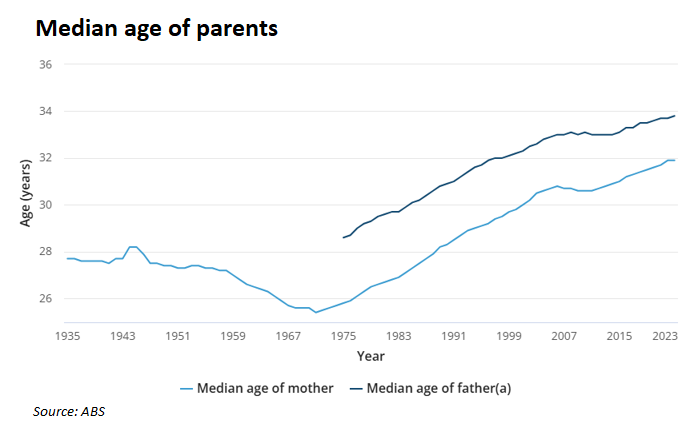

The ABS also reported that the median age of parents hit a record high of 33.8 (fathers) and 31.9 (mothers) in 2023.

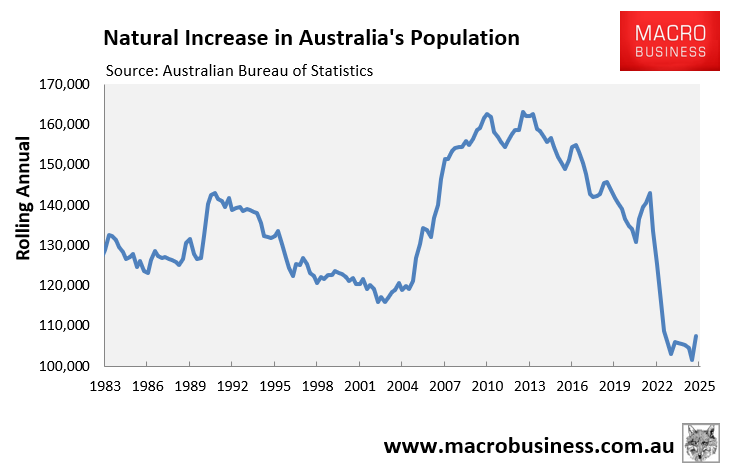

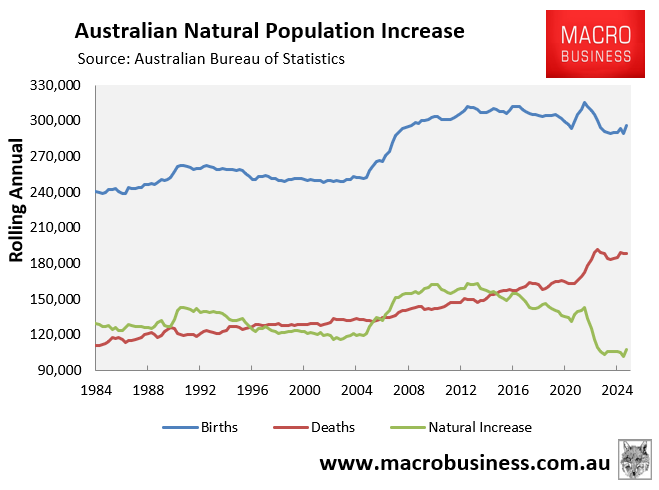

Last week’s Q1 2025 population data from the ABS showed that “natural increase” (i.e., the number of births minus deaths) was a historically low 107,500 over the year, near the lowest level on record.

Over the year, there were 295,900 births and 188,400 deaths, with the latter increasing as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic and the steady ageing of the enormous baby boomer group.

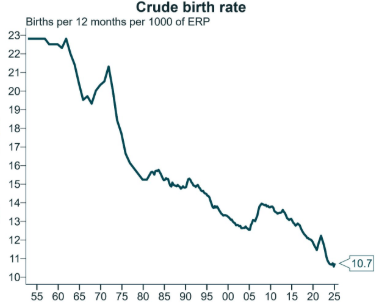

As shown in the chart below from Alex Joiner at IFM Investors, Australia’s crude birth rate—i.e., annual births per 1000 resident population—has fallen to 10.7, the lowest number ever recorded:

Source: Alex Joiner (IFM Investors)

Australia’s birthrate has been declining for 70 years and is now less than half that of the ‘baby boom’ in the 1950s and early 1960s.

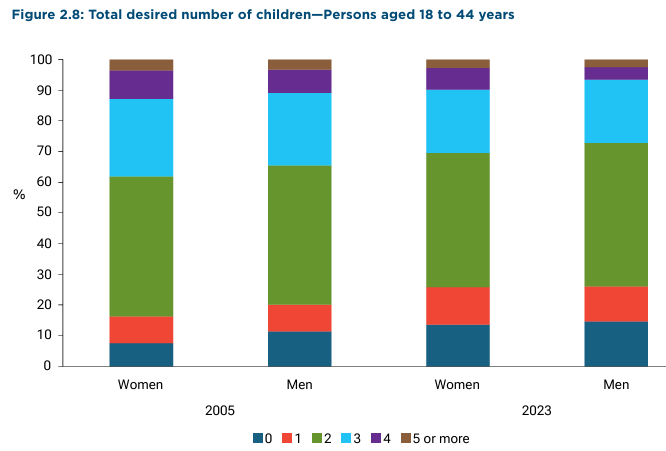

The University of Melbourne’s latest Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey has revealed Australians are opting to have fewer children than was the case 20 years ago.

Source: HILDA 2025

“There is also an evident trend towards a preference for small families and for childlessness”, the HILDA report says. “The share of persons desiring no children saw the largest increase of all groups, rising from less than 8% to around 14% among women and from about 11% to close to 15% among men”.

“Furthermore, the share of those favouring a one-child family increased from less than 9% among both genders to around 12% among women and 11% among men”.

“By contrast, the shares of people who would like to have three, four, or five or more children declined among both genders between 2005 and 2023”.

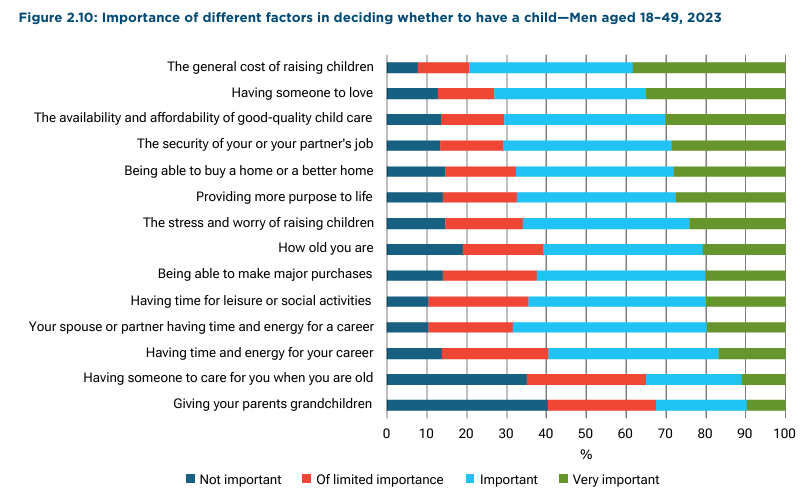

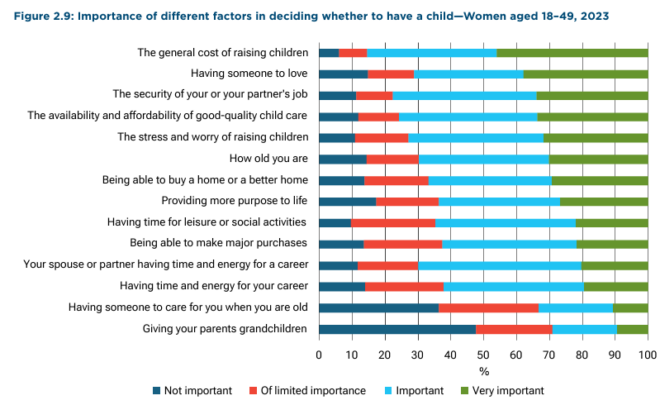

The HILDA survey showed that financial concerns are behind the decline in willingness to have children.

The general cost of raising children was rated the most important factor for women and men when deciding to have children. Other financial concerns like the partner’s job security, the cost of childcare, and housing also ranked highly.

Separately, the HILDA survey showed that factoring in inflation, households spent an average 38.5% more on childcare in 2023 than in 2006, and 40.5% more on rent.

While not the only factor, rising housing costs are clearly a barrier to couples having children.

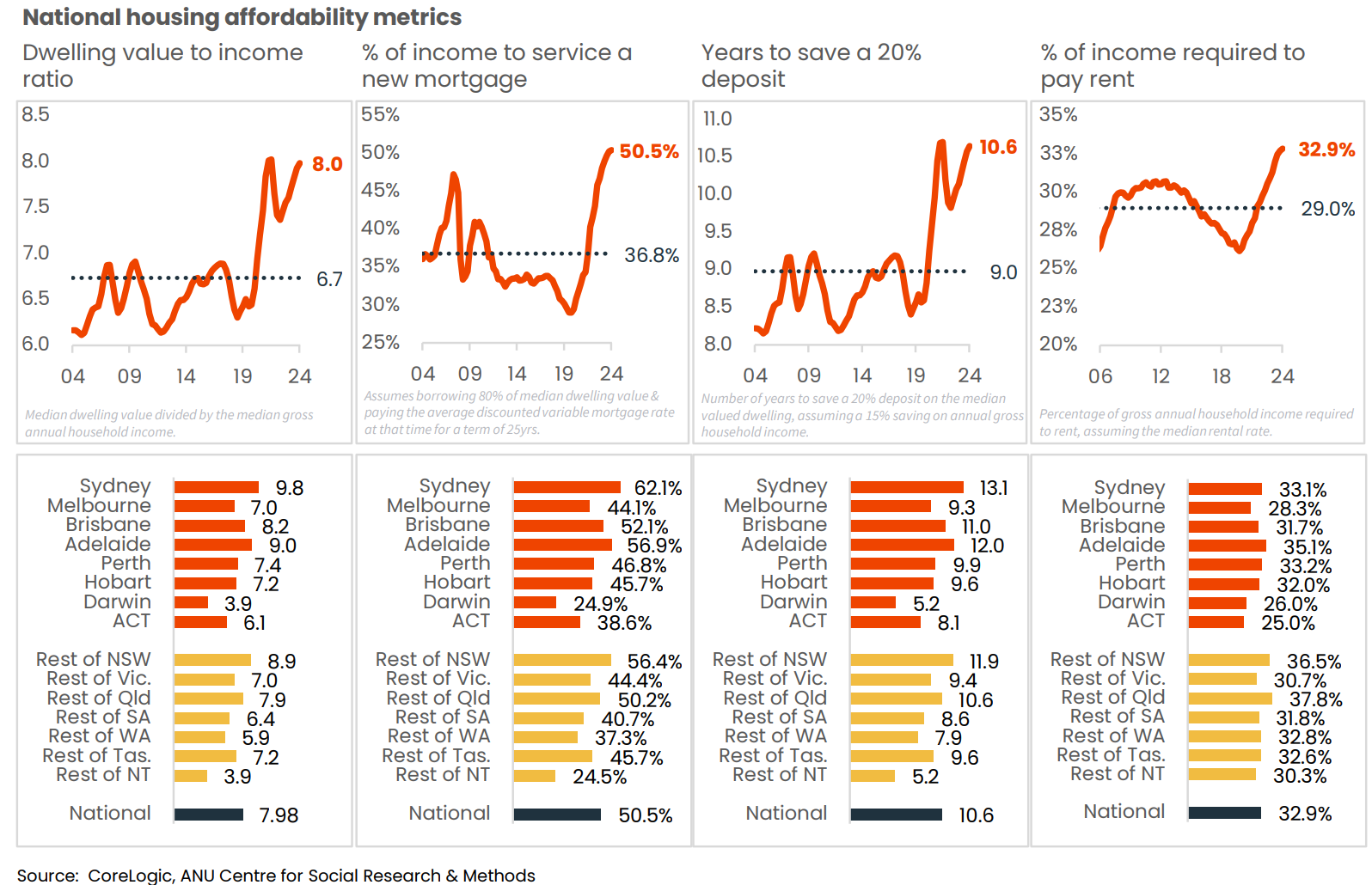

As shown below by CoreLogic (now Cotality), the cost of buying and servicing a mortgage on a property reached a new high by the end of 2024, as did the cost of renting.

According to HSBC research, “a 10% increase in house prices leads to a 1.3% drop in birth rates, and an even sharper fall among renters”.

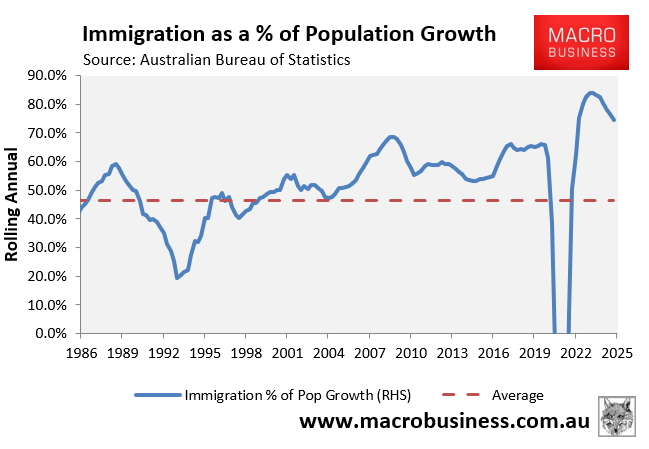

Historically high immigration has been a significant driver of Australia’s rising housing values and rents. As a result, it is also contributing to the country’s declining birth rate.

Australia’s immigration policy has generated a negative feedback loop. High migration rates, along with a scarcity of housing, have driven up home prices and rents. This, in turn, has contributed to a decreased fertility rate, which has resulted in the government using immigration policies to offset population ageing.

As a result, net overseas migration makes up a historically large proportion of Australia’s population growth.

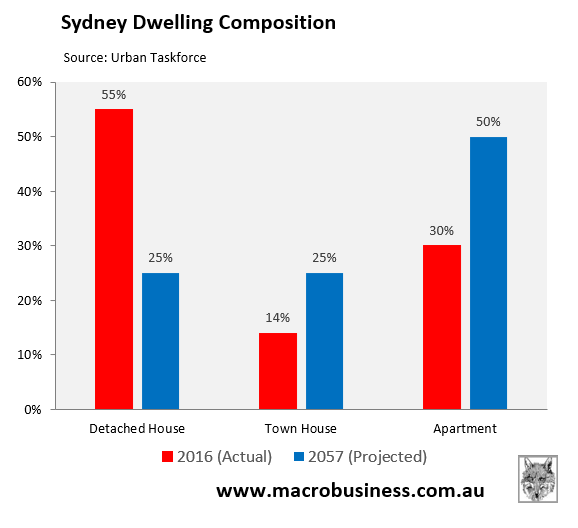

Immigration-driven population growth has also altered (and will continue to do so) the composition of housing in our main cities, from family-friendly houses with backyards to family-unfriendly one- and two-bedroom high-rise apartments.

Simply put, Australia’s immigration and housing policies discourage couples from starting families. Housing and the associated costs of raising children have made families a luxury in Australia.